4

4

Roni Horn at the Bourse de commerce : interview with a major artist, discreet but committed

Contemporary-art legends Roni Horn and Felix Gonzalez-Torres both redefined the exhibition as a medium, turning it into a fluid, evolving experience that places the viewer at its heart. Until September 26th, an exhibition at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce brings together these old friends, who also shared a political and militant stance. For Numéro Art, Roni Horn spoke to the show’s curator, Caroline Bourgeois.

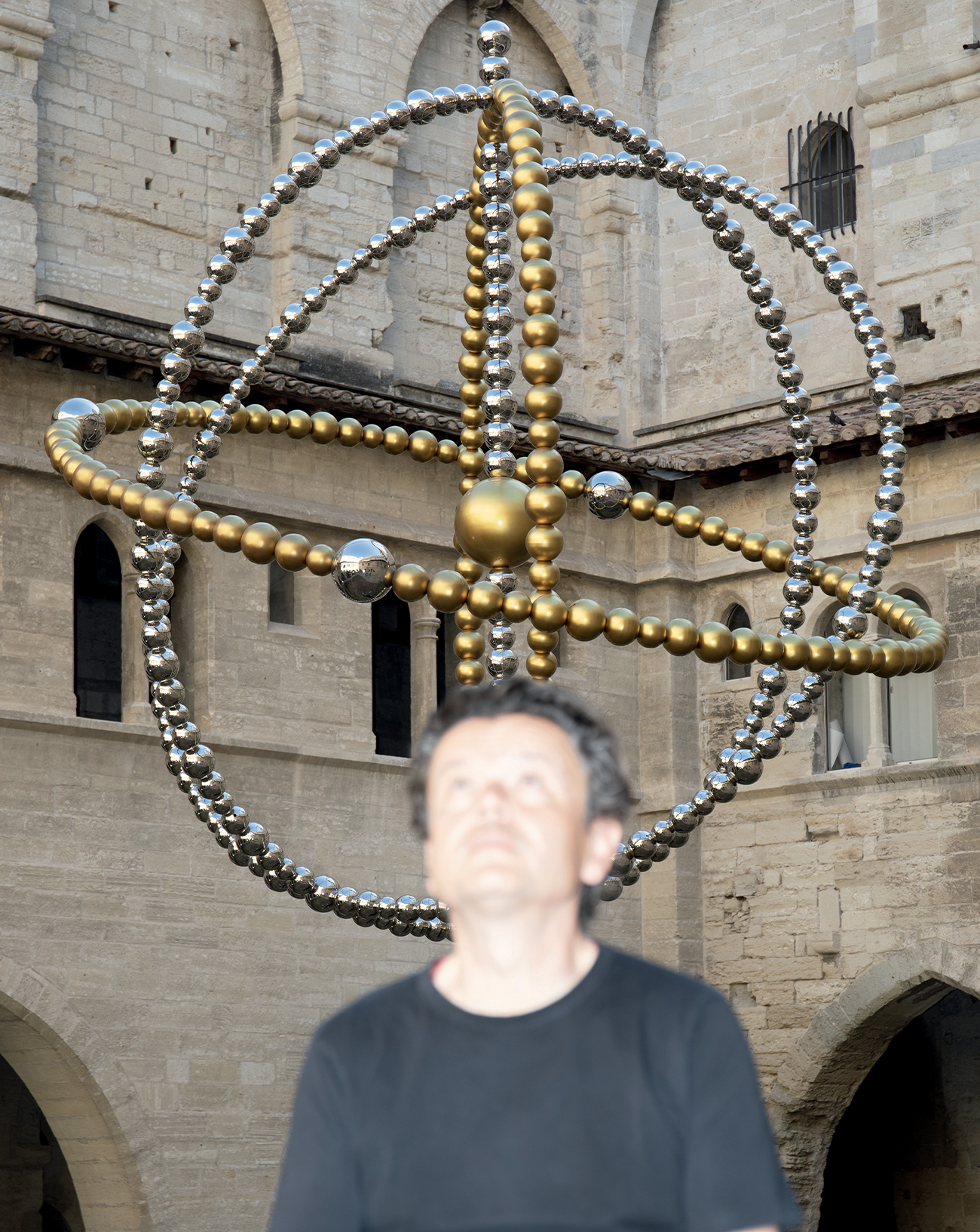

Portrait by Juergen Teller,

Interview by Caroline Bourgeois.

Caroline Bourgeois: This exhibition-dialogue between you and Felix Gonzalez-Torres was inspired by a connection we noticed between two of your key works [Gold Field and a.k.a] and two of his, Untitled (Blood) and Untitled (For Stockholm), which were never shown till now. Knowing you were friends, I suggested hanging these four works together and including in the catalogue a letter Felix sent you after you first met. We’re also publishing the homage to him you wrote after his AIDS-related death in 1996…

Roni Horn: I met Felix at the same time as Julie Ault, in 1990. It was at Indochine, a restaurant in New York. Felix wanted to talk to me about my exhibition that year at MOCA, which was my first show in a US museum. At that time, AIDS was a death sentence. There was no treatment, and nothing was really being done to protect people. It was a highly politicized disease because it seemed to strike what you might call unconventional sexualities. It was very easy for Reagan to say “They got what they deserved” until it became clear that heterosexual men could get it too, and that they were infecting their wives, and so on. Now we’re so close to finding a vaccine, I think about it all with great sadness the timeline of events, Felix’s death. I knew from the moment we met that I was going to lose him.

People were already taking very militant stances: Julie Ault was part of the conceptual artists’ collective Group Material, and of course there was ACT UP.

ACT UP became a very important movement in the late 1980s. It literally showed what was going on in parts of society that most people had no idea about. And Felix was very politically engaged, of course. I had political conversations with him, and we shared the belief that art is inevitably political. But does that mean it has to be topical or thematic? Perhaps that’s no longer a relevant question today… In any case, ideas of public and private were an important part of our conversations. Felix liked to play with public space by introducing images with no overt economic or political appeal into it on billboards, for example, which almost no one was doing at the time. He played very effectively with disjunctions, placing something enigmatic in a highly frequented yet very mundane environment, because he was addressing a popular audience, the passer-by, the average person, the street, not the museum-goer or the art collector. I found the connection he managed to establish very powerful.

His 1991 billboard Untitled, which shows a black-and- white photo of an empty double bed with slightly rumpled sheets, was shown on more two-dozen billboards in Manhattan as a tribute to his partner, Ross Laycock, who had died of AIDS-related complications that year. The intimate and the private became public and political, a key transposition in his work. The question of public and private, of identity, is also present in your oeuvre. I read somewhere that you had already under- stood by then that your gender was your decision alone, nobody else’s. That was a radical position at the time.

My gender is indeed nobody’s business. It’s something I became aware of as a child. I realized that social conventions were largely based on gender determination, and understood that it was something I couldn’t accept.

It’s a powerful stance that you and Felix shared, and I hope it will come through in the exhibition, this questioning of both identities and the works themselves as something living, the very opposite of an object. It will also allow us to play with the display of the works, as is already the case with Well and Truly [2009–10], which changes each time it’s installed.

Absolutely, the opposite of an object. For me, there’s some- thing very powerful in that it emphasizes the idea of a relationship, which I think is essential. Objects are illusions too. The idea that a person has a specific identity is an illusion to the extent that, in every person I know, there is a subtly different and changing self, which I know is true for every- one. When someone dies, you realize that everyone knew that person differently. It’s the same with eyewitness accounts you realize how unreliable they can be. There is something about relationships that makes the material world less finite, less limited. It becomes a set of relationships. I’ve always thought that the real meaning of my work is the experience of it. I can talk about it, of course, but in the end it all depends on you. I know I offer something very specific to look at, but it’s also entirely based in the hope, the wish, the desire that through this relationship, this link, the meaning will emerge in the viewer.

This is another thing you have in common with Felix, but in a different way. With him, we also find the object, which is unique but which can be made available to everyone. We can take a part of it with us. And we can physically carry the memory of it, that is to say a fragment… In his case, the objects are always reproduced in situ, for the exhibition. For example, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) [1991], which is made of candy wrapped in shiny paper and whose physical form changes de- pending on how it is installed. Ideally it should weigh 175 pounds, which is the average weight of an adult male. When visitors take a piece of candy with them, the weight and volume of the piece decrease.

There you have all Felix’s radicality and lucidity. This way of liquidating the materiality of the work and handing it over to the owner, or the viewer, and saying, “Here, go ahead, do it, it’s yours.”

“We live through and in the artwork. It’s not a superficial relationship. To experience it, you have to be there, you have to be present, you have to be fully attentive”

This is something else you share with him and that appears, in a different way, in Well and Truly [2009–10], for example, which offers a fluid, liquid and rather fascinating experience. Water is often present in your work – for me there’s a link with the idea of nature. You’ve been very active in Iceland, very engaged…

It’s interesting that you bring this up, because for me water is like a mentor. As a child, my connection to water was already very strong, even if it wasn’t precisely articulated and was just content to be what it was. When I made Library of Water [2003–07], this collection of samples from glaciers all over Iceland, displayed as columns of water that brought the landscape into the room, I said to myself: “Okay, what are you doing here? You’re taking a transparent substance and putting it in a transparent tube. Fine, but what are you expressing with that? It’s transparent so what? Who cares?” And yet the result turned out to be so much more visual and engaging than I’d imagined. I liked the idea that there would somehow be nothing to see, but I was completely wrong about that. I think that in reality this idea of collecting water from different sources across Iceland was something that was important to me personally. I also felt that it was conceptually relevant. Today, some of the water in those columns is all that’s left of the disappearing glaciers.

We’re also showing the drawings from your 2016 series Dogs’ Chorus and your work around Emily Dickinson.

Dogs’ Chorus consists of a series of works that take clichés as their starting point. For me, the ready-made expression is a kind of linguistic icon, and I’ve always conflated the visual and the linguistic – I’ve never chosen one over the other. It’s the same for male and female: I refuse to choose, I want both. Words have always very naturally permeated my work, and I’ve never conceived of, nor wanted, nor represented a hierarchy between language and the visual. The Dogs’ Chorus series starts each time with three clichés, three English-languague expressions, for example, “a bat out of hell,” “at the drop of the hat” or “a fly in the ointment.” I then interweave these expressions with the phrase “dogs of war” – taken from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “Let slip the dogs of war.” A different relationship forms between the phrases that are cut up and reassembled. It’s not a violent act in itself, but when you take something apart and put it back together differently, it’s like a kind of meditation on meaning, or realignment of the language, of its content.

You and Felix are both political, in a way that empowers the viewer. To me, this seems far more effective than any didactic approach that only has short-term influence.

We live through and in the artwork. It’s not a superficial relationship. To experience it, you have to be there, you have to be present, you have to be fully attentive, which people aren’t so much these days. To me, the beauty of art lies in this dynamic with the viewer, which gives rise to a truly intimate and precise opportunity.

This conversation-exhibition with Felix is being shown at the Bourse de Commerce in the heart of Paris, which brings us to another thing you both shared – he very much liked Paris too.

For me, Paris is like a big forest. I find that every street and every vista is somehow seductive. When I started out as an artist, I was fascinated by French cinema and the Nouvelle Vague. And by French authors too. During my studies at Yale, I watched a lot of films. There was a film library at the university you could reserve the screening room and book a slot to see this or that film, whatever you wanted. All you had to do was sit down and watch Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped, for example. I also watched The Trial of Joan of Arc, a film that definitely influenced me a great deal on You Are the Weather [1994–96]. By the way, on that subject, did you know that 12% of Americans believe Joan of Arc was married to Noah, as in Noah’s Ark? That says an awful lot about America…

Felix Gonzalez-Torres – Roni Horn, of Roni Horn, until September 26th at the Bourse de commerce, Paris.