12

12

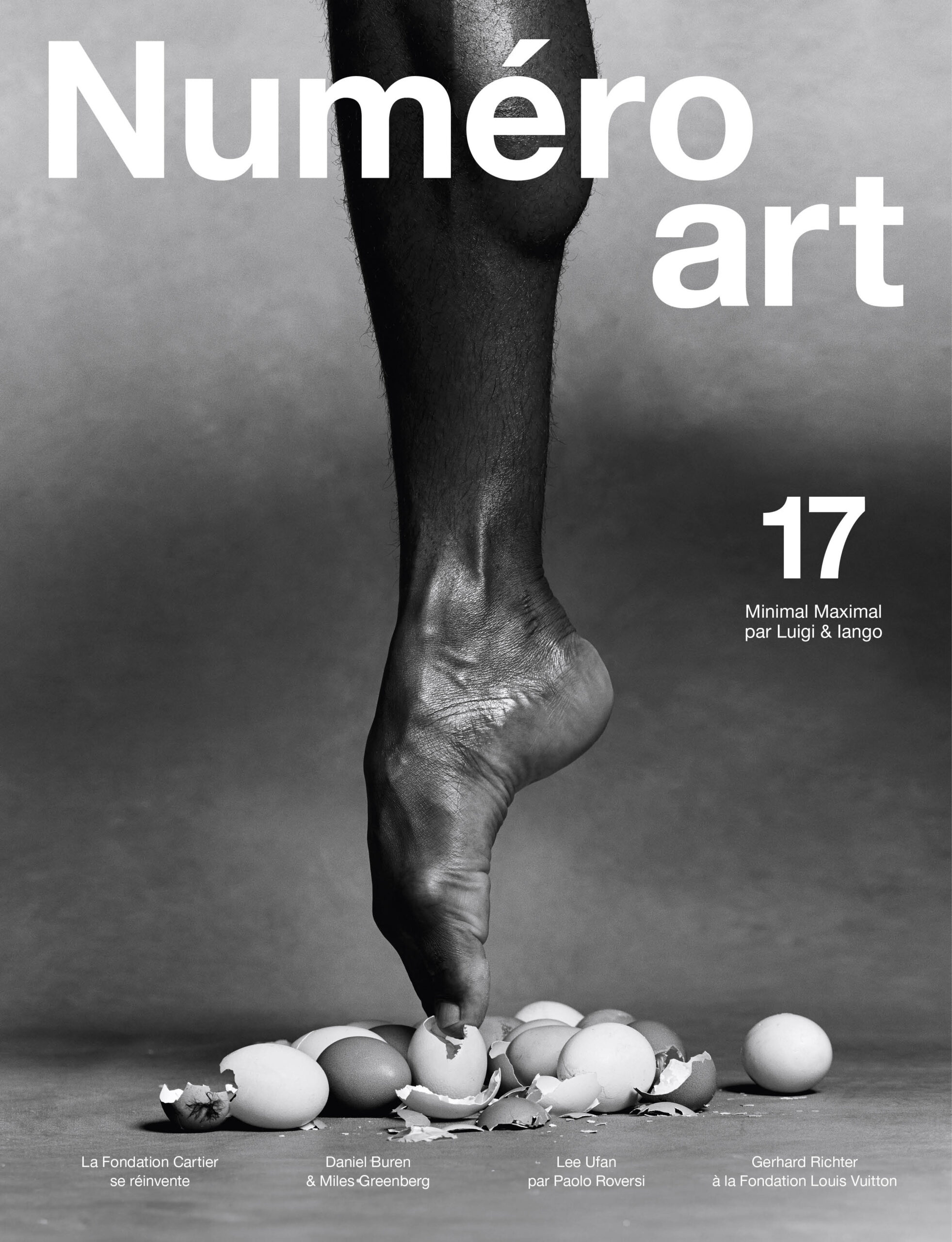

Minimal at the Bourse de Commerce: Behind the scenes of a landmark exhibition

After Arte povera last year, the Bourse de commerce is celebrating another major 20th-century movement: Minimalism. For Numéro art, James Meyer, a renowned specialist in the field, sat down with Jessica Morgan, director of New York’s Dia Art Foundation, who curated the exhibition. Showcasing masterpieces from the Collection Pinault alongside exceptional loan works, Minimal highlights just how much the movement’s legacy still reverberates today.

Interview by James Meyer .

Interview with Jessica Morgan, curator of the exhibition “Minimal” at the Bourse de Commerce

James Meyer: You’ve organized your exhibition in seven categories: “Light,” “Mono-ha,” “Grid,” “Monochrome,” “Balance,” “Surface,” and “Materialism.” How did you come up with these themes?

Jessica Morgan: Well, fundamentally, the exhibition did not start from an art-historical premise but from a very personal private collection, that of François Pinault. Therefore, it was clear to me from the beginning that there could be no strict chronology, because in order to really show the collection, we would be moving outside of specific moments in time or specific geographies.

This was never going to be a capital-M Minimalism show, because the collection really expanded in other directions, including Mono-ha. So then we started thinking about what the characteristics of the work were at that time across geographies and how we could articulate these, I hope, meaningful categories, which would neither reduce the works themselves nor the artists, but rather represent questions that were indeed interrogated as shared concerns in Japan, Brazil, Paris, New York, or wherever.

“This was never going to be a capital-M Minimalism show, because the collection really expanded in other directions, including Mono-ha.” – Jessica Morgan

![Dan Flavin, Alternate Diagonals of March 2 (1964) (to Don Judd) [1964]. Red and gold fluorescent light (Pinault Collection).<br>View of the exhibition “Minimal”, Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Niney and Marca Architectes, Pierre-Antoine Gatier agency. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur / Pinault Collection.](https://numero.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/minimal-bourse-de-commerce-exposition-numero-art-23-1024x683.jpg)

You’ve just said this couldn’t be a Minimalist show per se, and in fact many of the works displayed can and have been described as “post-Minimalist,” an open-ended term coined by the critic Robert Pincus-Witten in the late 60s to describe a set of formal possibilities opened up by Minimalist practice. Many works in the show share some of the concerns of historical Minimalism: an interest in “reduction,” purging the unnecessary; the particular qualities of materials exploited and revealed; geometric shape; somatic scale (sizing the work to a viewer’s body).

In your catalogue text you speak about a rejection of the strict “Calvinism” of Minimalist aesthetics. That made me chuckle. The notion of a “minimal” art came about to describe the three-dimensional work of Robert Morris, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Anne Truitt, and Sol LeWitt, among others. It then came to be applied to the painting of figures like Frank Stella, Brice Marden, Jo Baer, and Agnes Martin. Eventually it came to mean all kinds of things: the serial tendency in music (Steve Reich, Philip Glass); a type of fiction (Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie); and, by the 1990s, a kind of high-end interior design (John Pawson).

“This word “minimal” was in essence a way, hopefully, of having some resonance now.” – Jessica Morgan

At this point, “Minimalism” even refers to a lifestyle, the trend among some younger people to get rid of all this stuff, this clutter in our lives. You chose to title the show Minimal. Why is this term relevant in 2025? How does it still function in an art context?

I think it was important to me to still include it, even though it’s not necessarily Minimalism, precisely in order to pose the question of what it is we can find at that juncture of time in the 60s and 70s, when so many artists were simultaneously relinquishing pedestals and placing sculptural objects on the floor, making works that are questionably somewhere between a painting and a sculpture, and so on.

What has always been fascinating to me is this kind of embodied experience, this sense in which the work really began to move into the viewer’s space. Trying to find some link point that would be more familiar to people, this word “minimal” was in essence a way, hopefully, of having some resonance now. As I was researching the topic, it seemed quite funny to me how today the term has absolutely zero relationship to art for most people. So how might we bring it back to that? Is there something still to be unearthed, or brought back into common parlance?

“Minimal” has meant so many things. All of the artists who came to be called Minimalists disliked the word, which, at first, had a lot of negative weight. It implied that an artwork didn’t offer enough to look at. Or a certain disdain when artists like Flavin and Andre used industrial materials in a very direct manner, or Judd and Tony Smith hired fabricators to make their works. The adjective “minimal” implied that the works of these artists weren’t “art,” or not art enough.

“All of the artists who came to be called ‘minimalists’ disliked the word.” – James Meyer

And then it emerged as the name of a movement, a style, in classic avant-gardist tradition. “Impressionism,” “Fauvism,” and “Cubism” were also insults initially. One of the benefits of your structure is its non-linearity. The categories are distinct, yet overlapping; one doesn’t succeed the other temporally or in any other way; they are equitable. The structure seems suitable to this particular building.

It’s not only a way to organize the collection, but to adapt the presentation to the Bourse de commerce. I wondered about that. You have the seven sections, but then give certain artists – On Kawara, Robert Ryman, Félix González-Torres, and Agnes Martin – their own spaces. Was that due to the depth of Pinault’s holdings of these artists’ works?

Exactly. And also, of course, Meg Webster, who occupies the central atrium, the Rotunda. François Pinault has a wealth of work by Ryman, Martin, Kawara, and then there are artists like Webster and Charlotte Posenenske who are really my additions, and who we’ve worked with extensively at Dia [a major lender to the show].

A question about your categories. I was particularly struck by “Balance.” Some of your themes – the “Grid” and “Monochrome,” for example – have inspired entire literatures. “Balance” is less obvious, less expected. How did you come up with that one?

I would honestly say it very much came from the work, but perhaps also back to this dialogue with the visitor, since many of these pieces have a tangible relationship to gravity, to balance, to something oftentimes quite precarious. And so you have a physical reaction to it, which is, “Oh! Is this going to fall? Is it going to drop? How do I navigate around it?”

“Many of these pieces have a tangible relationship to gravity, to balance, to something oftentimes quite precarious.” – Jessica Morgan

And that seemed to be such a shared condition they were playing with in so many of these works, whether it was demonstrating the weight of a material, referring to an industrial process, or even a more traditional process that involves weights, or really thinking about the dialogue between form, materiality, and the space itself. It was striking to me that so many artists had explored this in one way or another.

The last category is “Materialism,” and includes works by Hans Haacke, Maren Hassinger, Walter De Maria, Dorothea Rockburne, Nobuo Sekine, Michelle Stuart, Kishio Suga, Jackie Winsor, and Iannis Xenakis. An interest in materials and materiality is a common concern of all the artists in Minimal. What makes the practices in this section uniquely “materialist?”

![Dan Flavin, Alternate Diagonals of March 2 (1964) (to Don Judd) [1964]. Red and gold fluorescent light (Pinault Collection).<br>View of the exhibition “Minimal”, Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Niney and Marca Architectes, Pierre-Antoine Gatier agency. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur / Pinault Collection.](https://numero.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/minimal-bourse-de-commerce-exposition-numero-art-20-683x1024.jpg)

View of the exhibition “Lygia Pape. Tisser l’espace”, Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Niney and Marca Architectes, Pierre-Antoine Gatier agency. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur / Pinault Collection.

“What I was interested in was the parallel history of Land Art.” – Jessica Morgan

What I was interested in was the parallel history of Land Art, which is impossible to bring physically into the gallery, although we gesture at it with Meg Webster’s piece in the Rotunda, which really is a kind of interior Land Art. I saw these artists as continuing that conversation, or perhaps troubling that history, whether through using twine and wood in the case of Jackie Winsor, creating something more geometric from something natural, or the kind of materialist immateriality you find with Haacke’s work, represented here by a condensation box, and Walter De Maria’s energy bar – energy is invisible, but we know that it’s there

I wanted to explore this sense in which materialism can be expanded to something quite abstract, emotional, or that even has a kind of Zen quality to it, and really think about the way in which artists were playing with the elemental qualities of the material they were working with, producing something that, again, references nature, but turns it in a very different direction.

![Dan Flavin, Alternate Diagonals of March 2 (1964) (to Don Judd) [1964]. Red and gold fluorescent light (Pinault Collection).<br>View of the exhibition “Minimal”, Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Niney and Marca Architectes, Pierre-Antoine Gatier agency. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur / Pinault Collection.](https://numero.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/minimal-bourse-de-commerce-exposition-numero-art-24-683x1024.jpg)

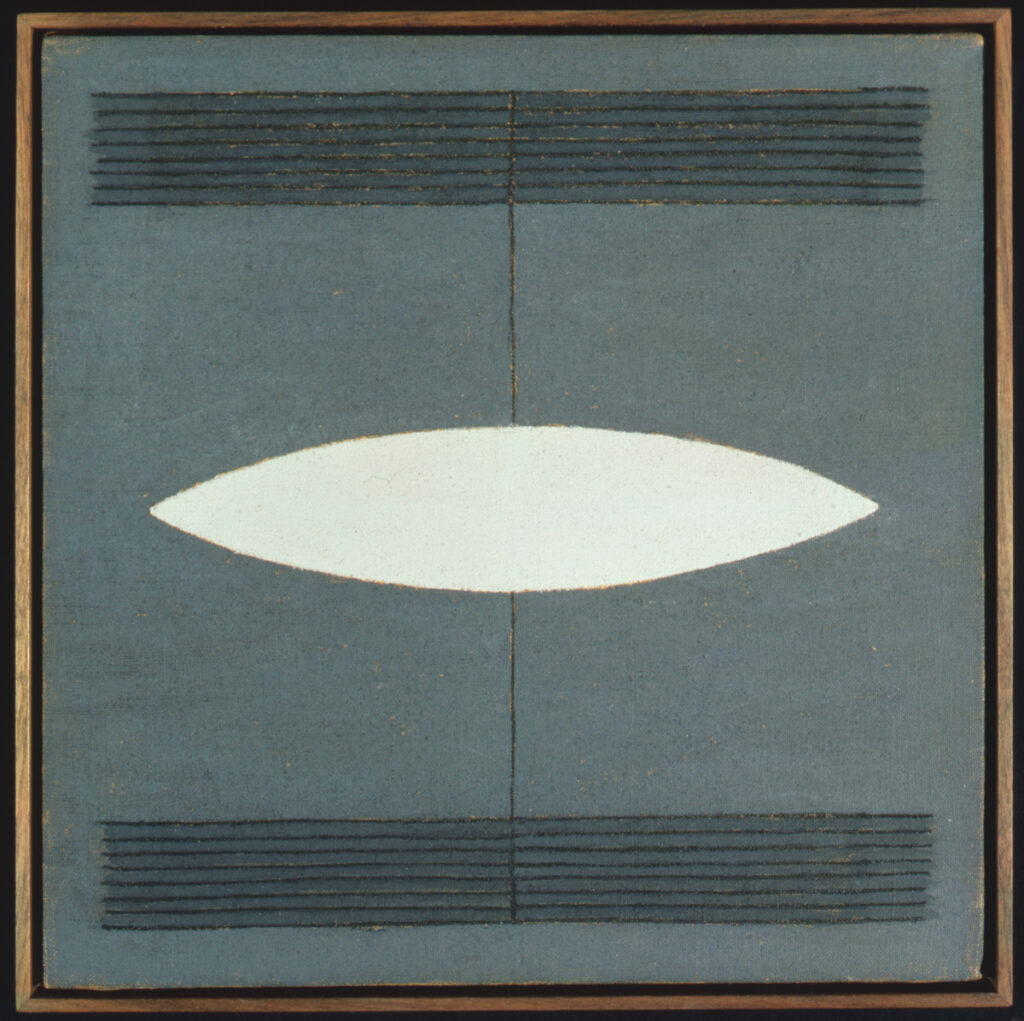

View of the exhibition “Minimal”, Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Niney and Marca Architectes, Pierre-Antoine Gatier agency. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur / Pinault Collection.

Can you share what Webster’s projects in the Rotunda will be?

Well, her work will inhabit an interesting space, with the historic ceiling painting that’s essentially a complex exploration of colonial extraction. So I’m excited about the fact that Meg’s work – large-scale installations that deal with locally sourced materials such as terre jaune de Commelle from Isère, terre rouge du Royans from Valence, sea salt from the Camargue, and local yellow beeswax, twigs, and flora—will be taking a very different approach.

Meg’s work really exemplifies this incredible ecological position she’s held now for decades, which was very much ahead of its time, but was also a landmark contribution to the art of its day with these extraordinary geometric forms. Meg’s participation is politically important too. Her work will have a very significant presence when you arrive. Which returns us to a fundamental question: when we think of Minimal art, are we thinking of steel? Are we thinking of bronze? Are we thinking of industrial materials? For here’s Meg Webster creating these very significant and impactful minimal forms entirely from natural materials.

“Minimal”, exhibition from October 8th, 2025 to January 19th, 2026, at Bourse de commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris 1st.