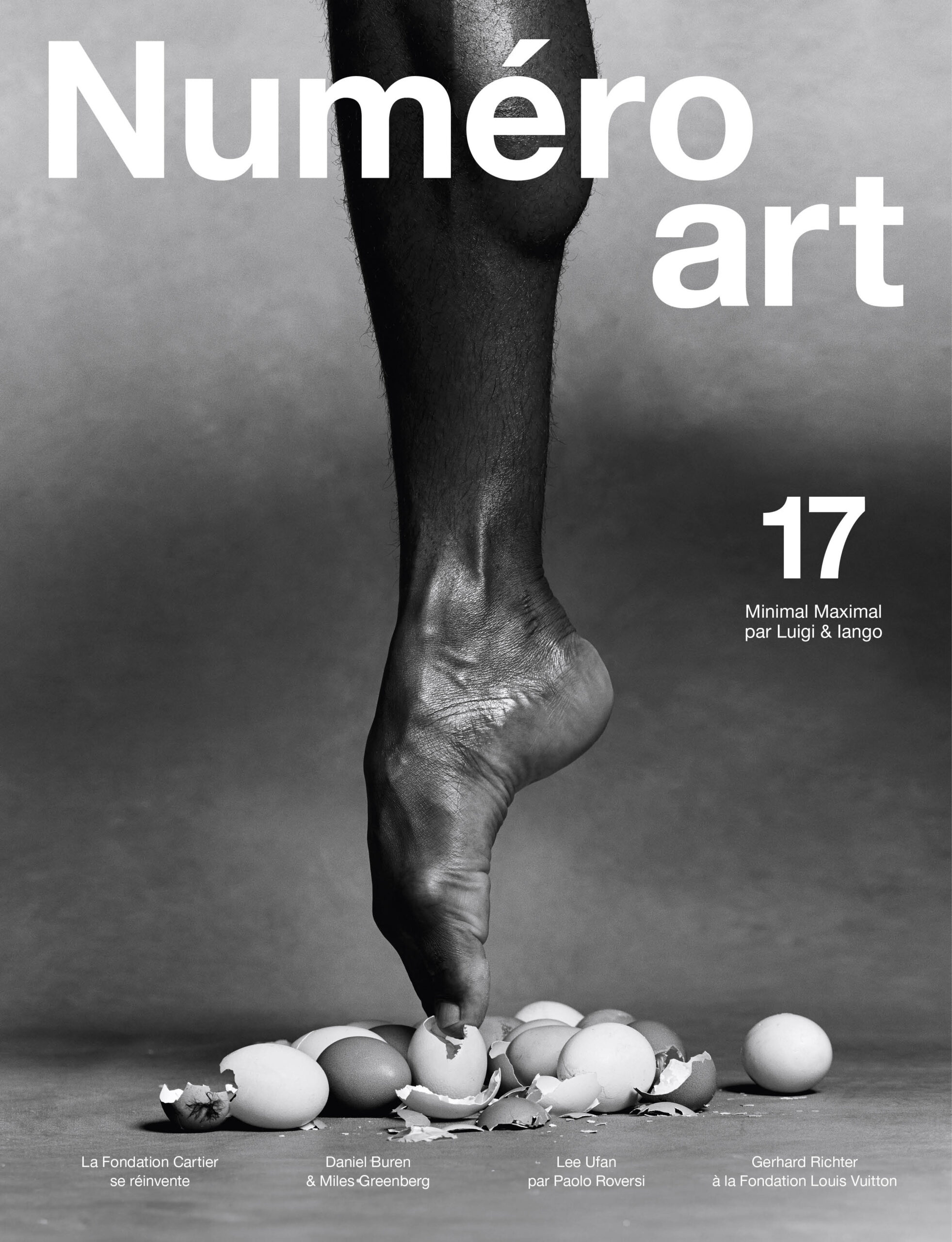

2

2

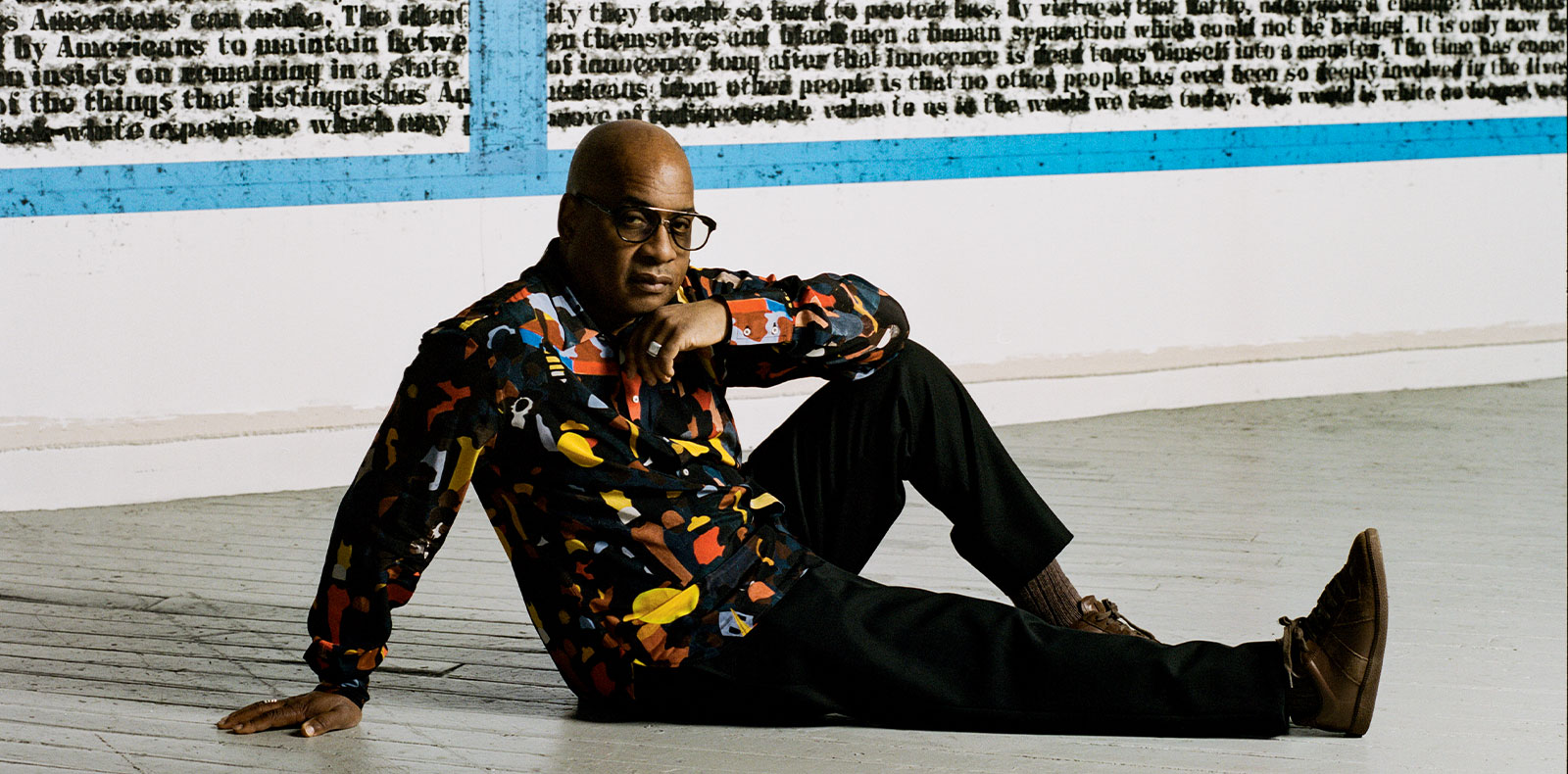

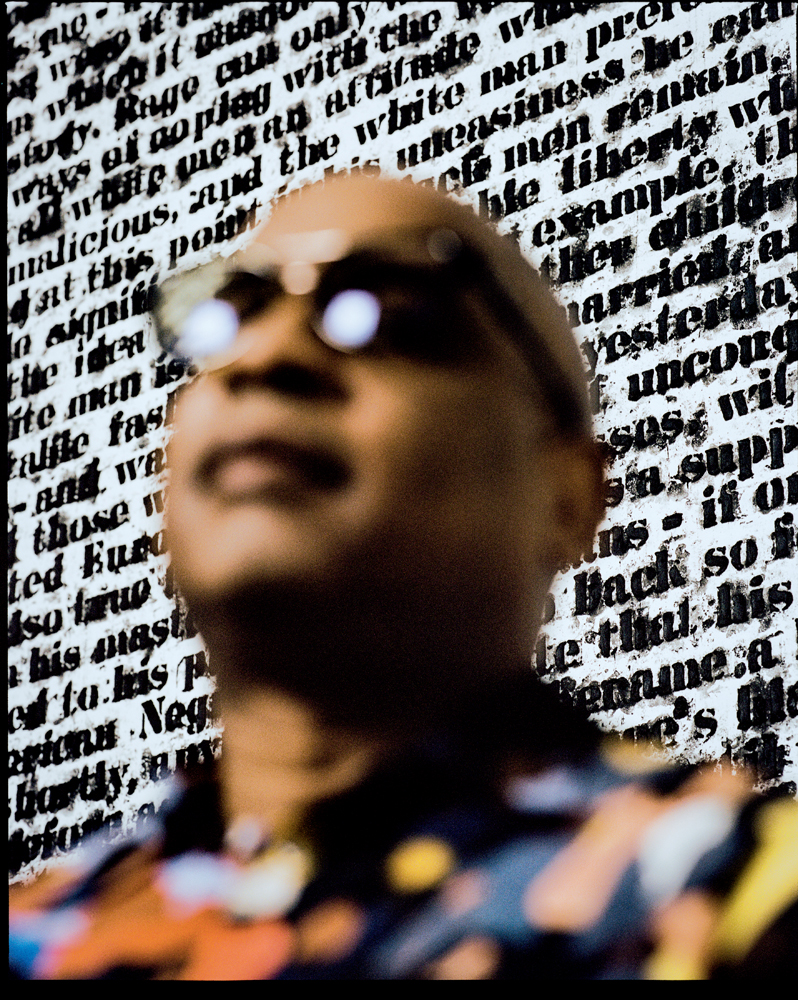

Meeting with Glenn Ligon, American art legend currently exhibited at the Carré d’art in Nîmes

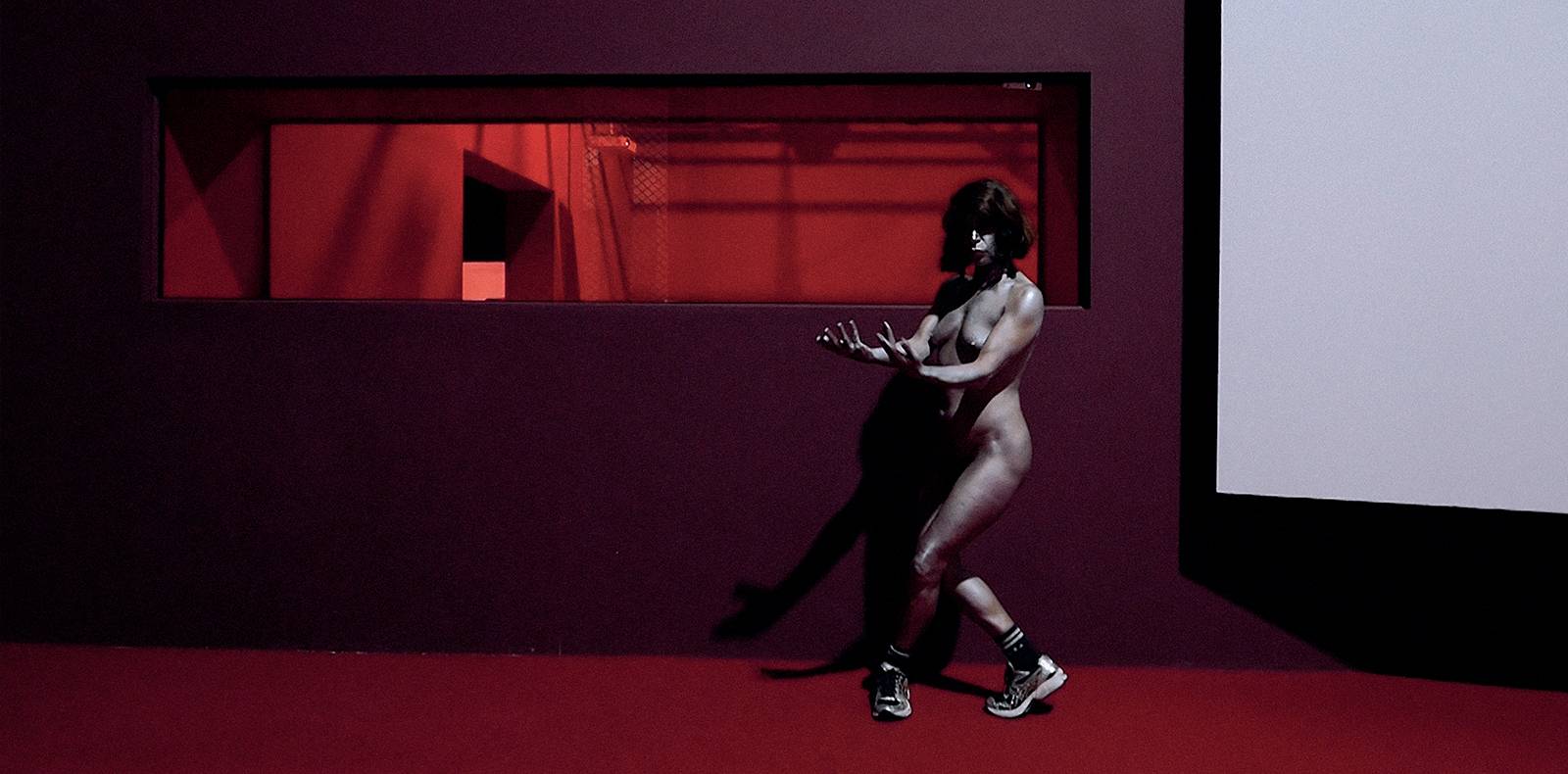

Since the mid-1980s, in a series of revelatory works, Glenn Ligon has been exploring american identity and questions of race and sexuality. Until now, this respected figure on the us scene had never been honoured with a solo show in france. from June 24th to November 20th, Le Carré d’art in Nîmes has at last put that right with its magnificent new exhibition, Post-noir, which occasioned the following conversation between ligon and art historian Huey Copeland.

Portraits by Dana Scruggs,

Interview by Huey Copeland.

“MALCOLM X WAS CONSIDERED BY THE FBI TO BE ONE OF THE MOST DANGEROUS MEN IN THE UNITED STATES. TODAY YOU CAN BUY A STAMP OF HIM. IT SAYS A LOT ABOUT HOW OUR VIEW OF ICONS CHANGES OVER TIME.”

And what about the Debris Field series?

This series is the result of a kind of experimentation I was doing with old leather stencils, which I normally use for my text paintings. I realized that so much of my work has been about taking text toward abstraction, but what if I started with the letterforms themselves, and took them directly to abstraction? What if I drew through plastic letter stencils with ink to see what shapes are formed? When I use ink as a material, it doesn’t retain the contours of the stencil, instead creating a distorted shape. What fascinated me was the idea of inventing a language, inventing a new form out of the letters themselves, and these paintings are much more improvisational because of that. They aren’t bound by lines of text or quotations but are much more about improvisation and composition.

In the same way I often start with Baldwin’s text or a kids’ colouring book, the process of making the Debris Field series started with source material. About five or six years ago, I made a set of etchings that I realized would make a good base composition for the Debris Field paintings. I took one of those prints to a silkscreener, had it blown up in scale dramatically and silkscreened it on canvas using etching ink, which is very stiff and creates voids and gaps, resulting in a ghostly appearance at times because the ink is not getting through the screen properly. Those were the first iterations of these paintings, in black and white, that I showed at the Thomas Dane Gallery in Naples in 2018. But then I wanted to work on them some more and realized I could make stencils of the abstract shapes in those paintings and then go back into them and stencil on top of the silkscreen.

The Debris Fields paintings in Nîmes include both the earliest iterations of those, which are mostly pure silkscreen with ink marker drawn on top, as well as the latest iterations with red back- grounds, with stencilled oil stick or etching ink on top of what had already been laid on the canvas. In that sense, they are much more like the traditional abstract paintings I used to make when I was first thinking about becoming an artist, in that I am really thinking about things like composition, whereas in text paintings there is a pre-existing structure. In some ways these works were more difficult to do, because I haven’t been engaged with those kinds of painterly decisions for a while. But there is also a kind of freeing up or liberation that occurs.

Huey Copeland: As is often the case in your work, the pieces in your Nîmes exhibition were produced by revisiting, quoting or annotating pre-existing visual and linguistic utterances, including your own. Could you talk more broadly about this creative process, and how it shaped some of the works in the show, such as the colouring-book series?

Glenn Ligon: Much of my work is citational in nature. For example, regarding the colouring-book works, I gave Afrocentric colouring-book images from the late 60s and early 70s to young kids, and I then used their inventiveness – the way they coloured those images in – to reflect on the distance between childhood creativity and its lack of boundaries around icons, and what is considered acceptable to do to a portrait. It’s a way of thinking about my own subjectivity, what I know about an image of Malcolm X, and all the historical engagement I bring to that image versus what a child might see, and how they’re going to react to and use that same image. In the same way, when I go back to my earlier work, I always try to approach it with a fresh eye. There is always a form of circularity in my practice. For my Stranger paintings, I look to James Baldwin’s 1953 essay Stranger in the Village and return to it repeatedly to create a series of works, one of which is included in the Nîmes show. This particular painting incorporates the full text of Baldwin’s essay and is the first time I’ve used it in its entirety, resulting in a canvas that’s almost 14 m long. It took me 20 years to get to this point, and that sense of working up to something is part of my practice.

“Painting has always been a touchstone for me, but I often find that I need to turn to other media in order to be able to deal with particular subjects more effectively.”

This moves you away from a painting on the scale of the portrait or the body, and brings you into dialogue with a radically different, though just as rich, American pictorial tradition.

This approach probably comes from my memory of the early giants of American painting – Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline, and Abstract Expressionism as a whole. But I am also deeply inspired and moved by the work of African-American artists Jack Whitten and Sam Gilliam, and the size of their paintings, their ambition in terms of what they were trying to address in their work through abstraction. When I was working on the Stranger paintings, I kept going to MoMA to see a Jack Whitten painting from the permanent collection. And every time I went, I found it different. That’s when I thought I wanted to paint something that would keep you coming back, just as I kept coming back to Baldwin’s Stranger in the Village.

You are mostly known – and rightly so – as a painter, but your exhibition in Nîmes also includes other media such as neons and video that seem to redefine and broaden our understanding of the conventional pictorial dichotomies that are figure/ground, gesture/composition, image/object, and so on. What does this prolifer- ation of techniques allow you to do that painting alone does not?

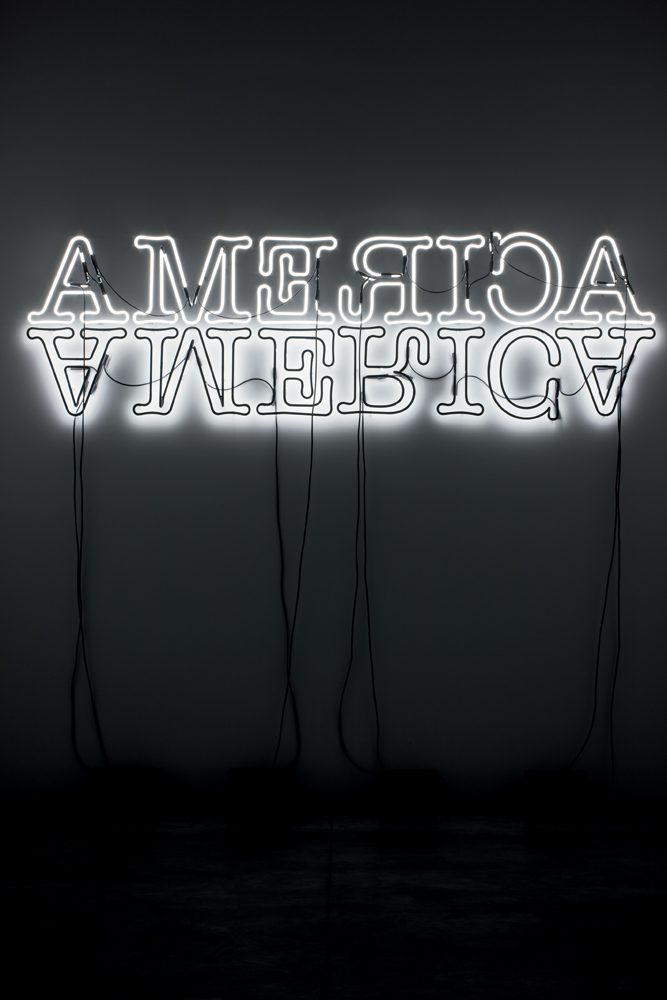

Generally speaking, I position myself first and foremost as a painter, but I realize that my painting practice is somewhat limited, though maybe it is only a limit of my own imagination. When I work with neon or with a film installation, I see these media as ways to do things that are not suitable for a painting project, or that I have not been able to approach through painting. I think of media as materials, in the same way that paint or even language are materials. The Americaneons, several of which are on view in Nîmes, encapsulate my thinking about the word itself as a material to be used, to be painted black, to be flipped horizontally, to be turned against the wall or to be flipped upside down. These neons have a connection to the painted word and the way language appears in my paintings, but they also allow me to move into the realm of sculpture. For me, painting has always been a touchstone, but I often find that I need to turn to other media in order to be able to deal with particular subjects more effectively.

“In the 1960s, the FBI labelled Malcolm X one of the most dangerous men in the US. But today, you can buy a stamp with Malcolm X’s image on it in any post office in America. This says a lot about how our view of icons changes over time.”

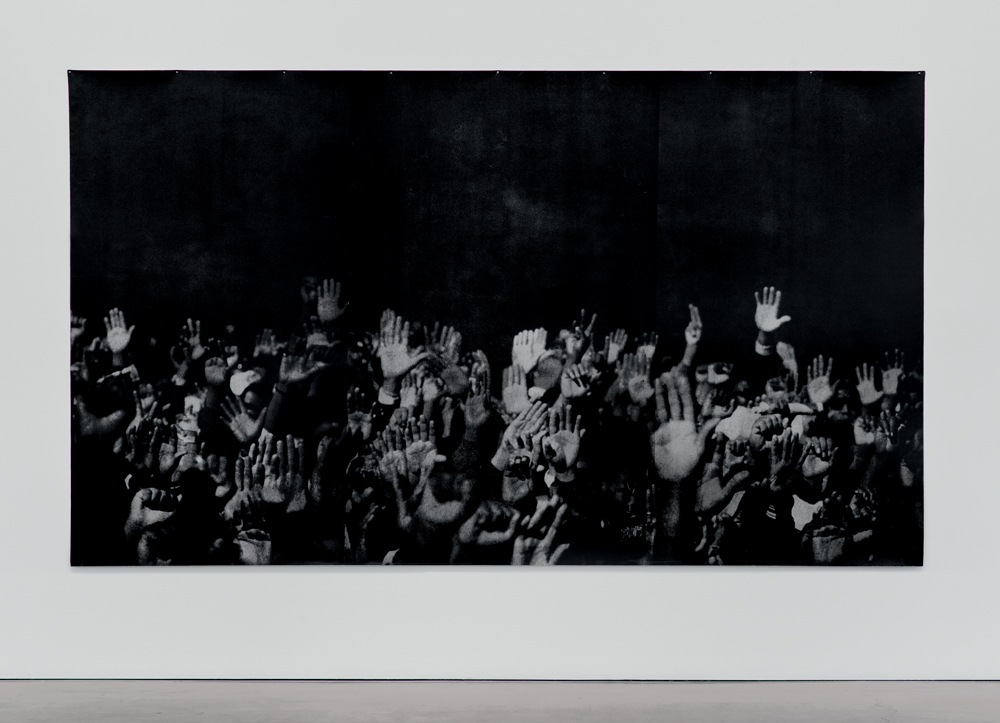

In your Nîmes show, several works depict American icons or reproduce their images, for example Malcolm X. Others, notably the Debris Field series, seem to want to break up the visual field – not to mention the “icons” that could emerge from it. Could you tell us more about this dialectic of recognition and fragmentation, and explain how it serves as a kind of critical strategy?

Like language, icons are constantly being made and re- made, and this idea has always been an operating principle in my work. For example, taking a word like “America” and using it as a material to be twisted, distorted, played with, or obscured. Or taking an icon like Malcolm X in order to think about how we treat the image of an iconic figure, how we choose to revise that image. What defines a historical moment? How was an image of Malcolm X perceived then as opposed to now? In the 1960s, the FBI labelled him one of the most dangerous men in the US. But today, you can buy a stamp with Malcolm X’s image on it in any post office in America. This says a lot about how our view of icons changes over time.

And what about the Debris Field series?

This series is the result of a kind of experimentation I was doing with old leather stencils, which I normally use for my text paintings. I realized that so much of my work has been about taking text toward abstraction, but what if I started with the letterforms themselves, and took them directly to abstraction? What if I drew through plastic letter stencils with ink to see what shapes are formed? When I use ink as a material, it doesn’t retain the contours of the stencil, instead creating a distorted shape. What fascinated me was the idea of inventing a language, inventing a new form out of the letters themselves, and these paintings are much more improvisational because of that. They aren’t bound by lines of text or quotations but are much more about improvisation and composition. In the same way I often start with Baldwin’s text or a kids’ colouring book, the process of making the Debris Field series started with source material. About five or six years ago, I made a set of etchings that I realized would make a good base composition for the Debris Field paintings. I took one of those prints to a silkscreener, had it blown up in scale dramatically and silkscreened it on canvas using etching ink, which is very stiff and creates voids and gaps, resulting in a ghostly appearance at times because the ink is not getting through the screen properly.

“What fascinated me with the Debris Field series was the idea of inventing a language, inventing a new form out of the letters themselves, and these paintings are much more improvisational because of that.”

Those were the first iterations of these paintings, in black and white, that I showed at the Thomas Dane Gallery in Naples in 2018. But then I wanted to work on them some more and realized I could make stencils of the abstract shapes in those paintings and then go back into them and stencil on top of the silkscreen. The Debris Fields paintings in Nîmes include both the earliest iterations of those, which are mostly pure silkscreen with ink marker drawn on top, as well as the latest iterations with red backgrounds, with stencilled oil stick or etching ink on top of what had already been laid on the canvas. In that sense, they are much more like the traditional abstract paintings I used to make when I was first thinking about becoming an artist, in that I am really thinking about things like composition, whereas in text paintings there is a pre-existing structure. In some ways these works were more difficult to do, because I haven’t been engaged with those kinds of painterly decisions for a while. But there is also a kind of freeing up or liberation that occurs.

How do you think your work will be received by the French public in Nîmes?

In some ways, it is a bold move to dedicate an entire room to America neons in a French institution. But I’m interested to see how a French audience might receive this work. People know I’m American and that my concerns are largely “American” concerns. Going back to James Baldwin, there is a documentary called From Another Place that follows him through the streets of Istanbul. At one point, he sees American warships in the distance, and we hear him say, “Ah, it’s impossible to escape American power.” There it is, that power, out in the distance. In one sense, I feel that, wherever you are in the world, you must somehow grapple with America. But I’m also interested in seeing how all of this will translate into the local context. What the exhibition means in that particular space could be very different from my own intentions, so naturally I’m curious. And guiding the idea of Post-Noir as the title rather than Post-Black is the question of translation that runs through the exhibition. There is currently a lot of debate in France about the ques- tion of francité and what Black identity means there. I want the visitor to think about how what I do enages with the cultural struggles of our time.