2

2

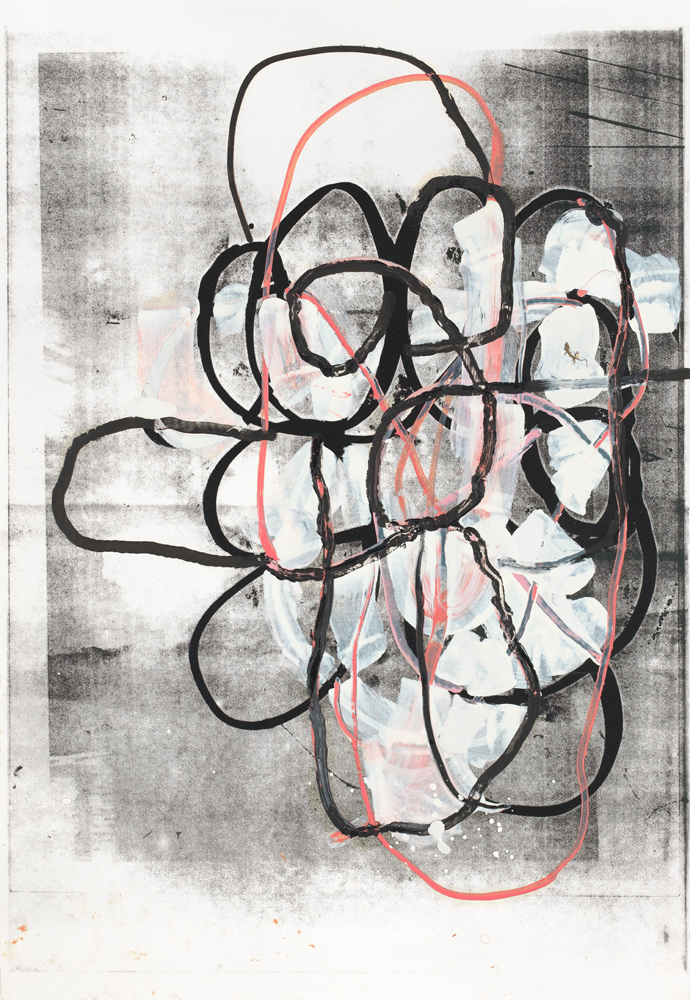

Meet artist Christopher Wool, the master who creates tension between painting and erasing, gesture and removal

Last June, Belgian gallerist Xavier Hufkens inaugurated the opening of his new space with a show by Christopher Wool (born 1955, lives in New York and Marfa, Texas). In this exclusive interview, Wool told Numéro Art about his idiosyncratic practice, which mixes and plays with all sorts of media and techniques.

By Nicolas Trembley.

Nicolas Trembley: After minimalism and conceptualism, the early 1980s saw the arrival of figurative artists. But you weren’t part of this discourse?

Christopher Wool: No, I think there was still a painting discourse. The late 1970s might have been a slow time in the art world, but when the Pictures Generation started showing – Julian Schnabel’s first show, etc. – there was a lot of dialogue about what was going on.

Would you say you come more from the Pictures Generation, with photography and film, or from paint- ing? People tend to talk more about your paintings…

Yes, I know. I came from the Studio School in New York, a more traditional, painting-oriented background. A lot of Pictures Generation artists rejected painting. I think I was just young enough – I was a year or two younger – that by the time the idea of rejecting painting had settled in, I didn’t need to. I could learn from them, the issues they brought up were important, but it didn’t stop me from painting.

You work with different media. Do you feel more at ease with a particular one or is it about the combination?

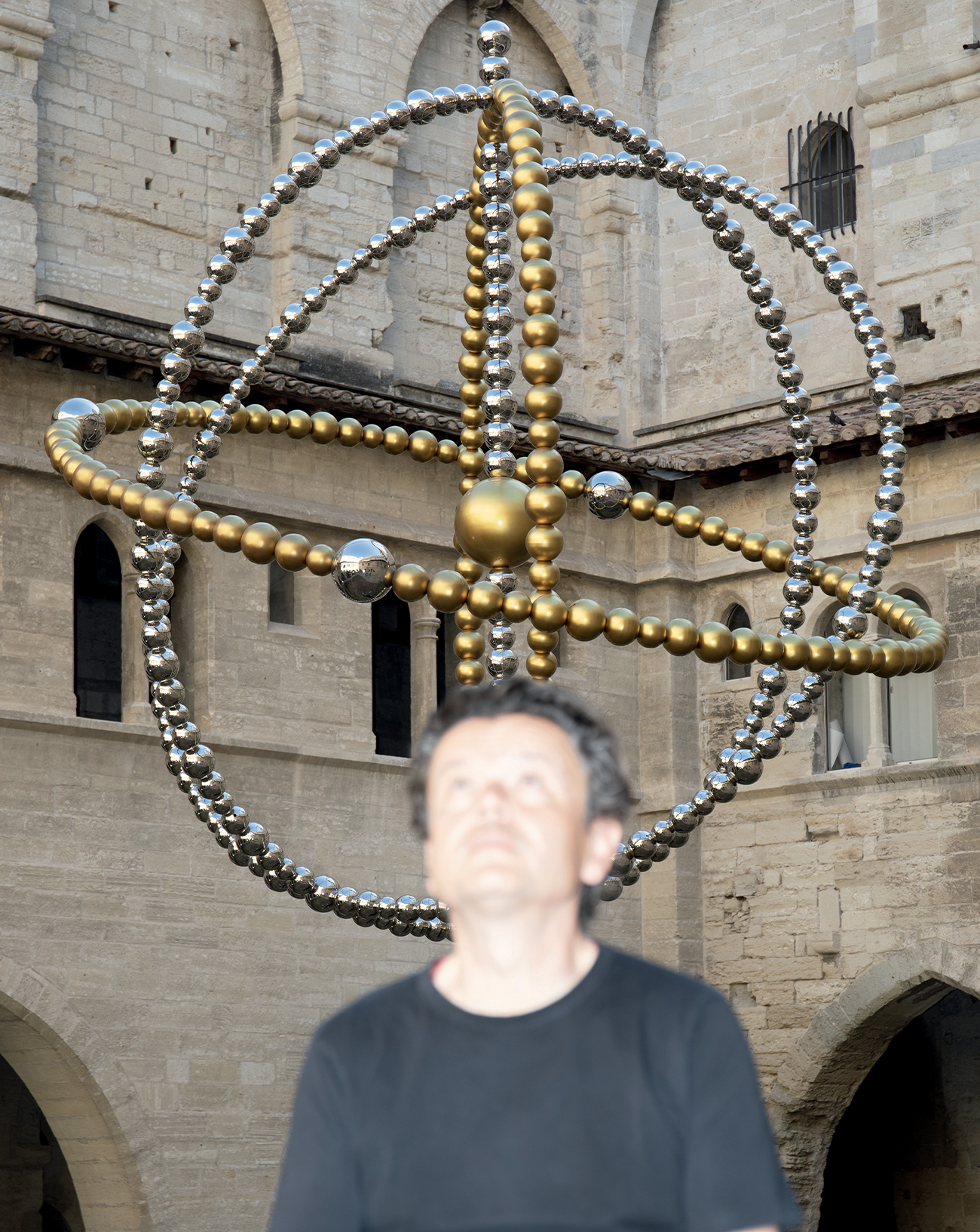

No, I think I’m still a painter mostly. Sculpture is new to me. Richard Prince described his use of photography as “practising without a licence”. I think that’s a great description, because I don’t think I come to photography like a pho-tographer would. It’s maybe the same for sculpture: I have to get used to three dimensions, it’s new to me.

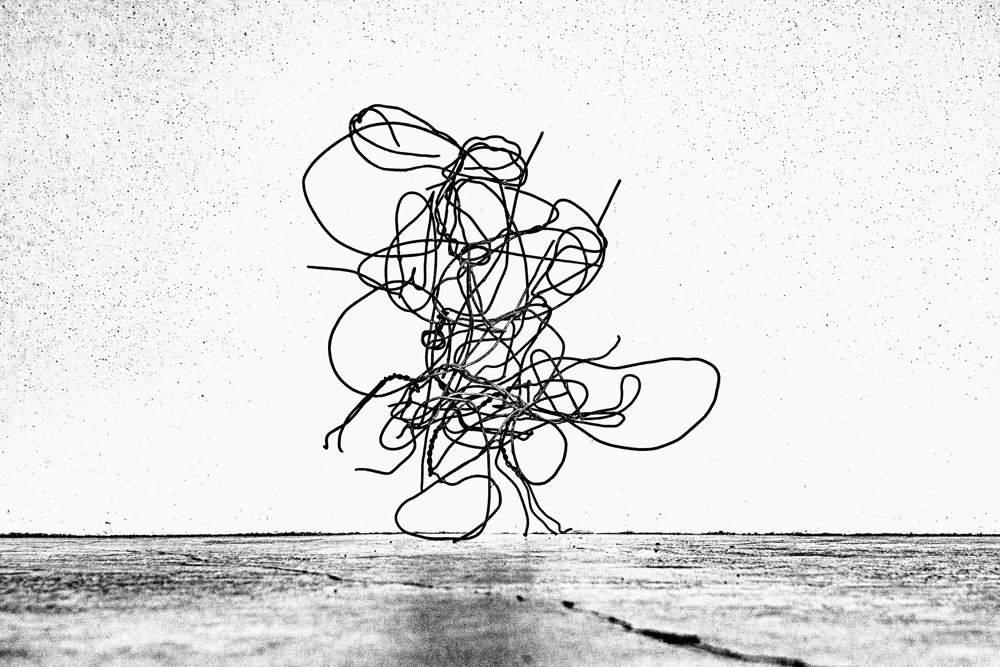

What got you started on sculpture?

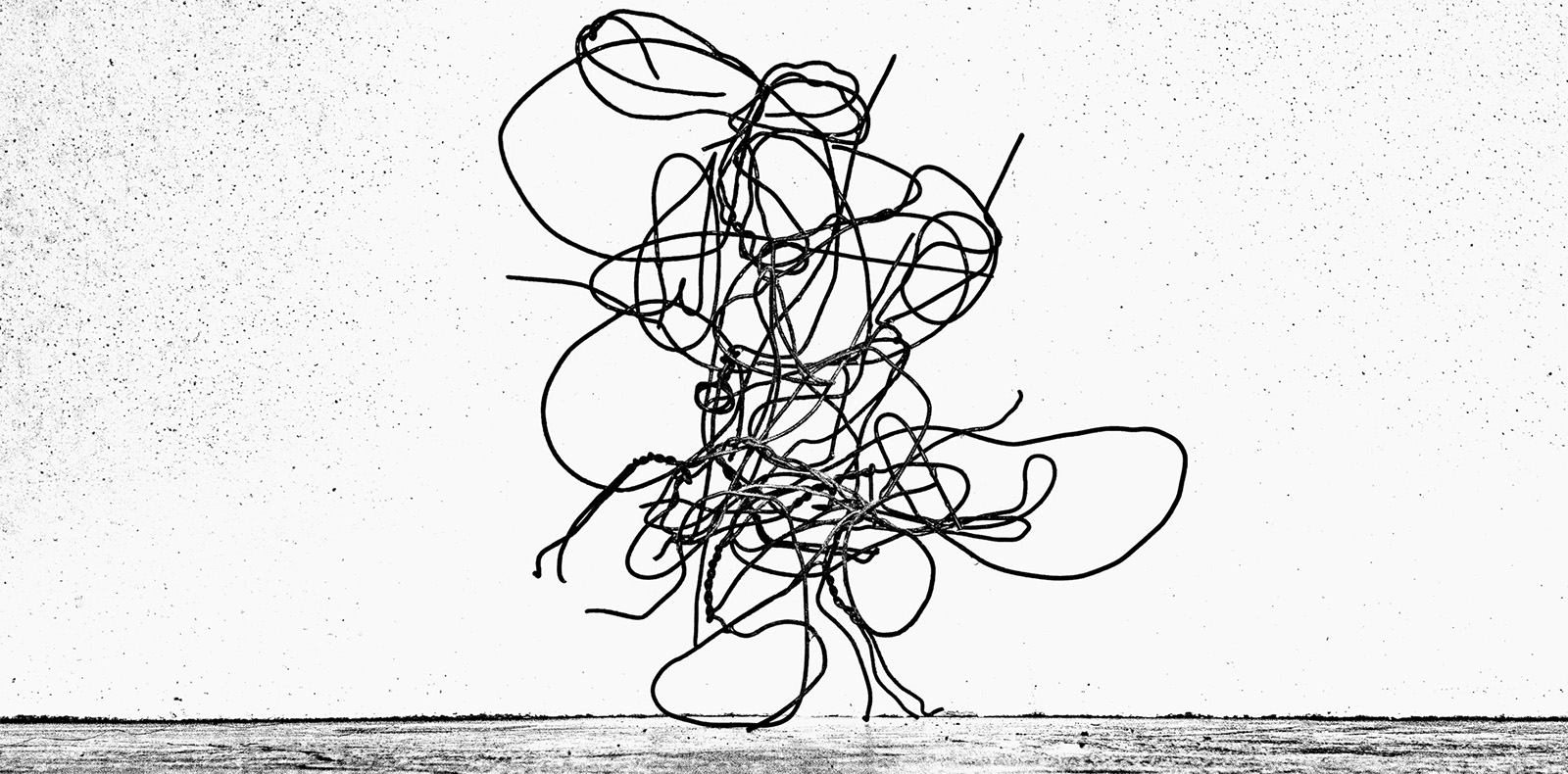

It was quite simple actually. When we first got a house in Marfa and started spending time there, it just seemed natural to think about larger three-dimensional things, just because there’s so much space. I had my camera and I started noticing funny, interesting, amusing things that were sculptural outside in Marfa – things people put in their yards in a silly way or any kind of industrial object. That became the book Westtexaspsychosculpture. The psychosculpture idea was borrowed from Kippenberger’s book Psychobuildings. So, I was thinking about sculpture without having any specific plans. Then I found all this fencing wire that was left around the ranch next to my house, which I picked up because it had a nice line to it, similar to the line I draw with. It took me a while, but eventually I started making the thing stand up and they became three-dimensional in a simple way. It took a few years before I actually got around to making it art.

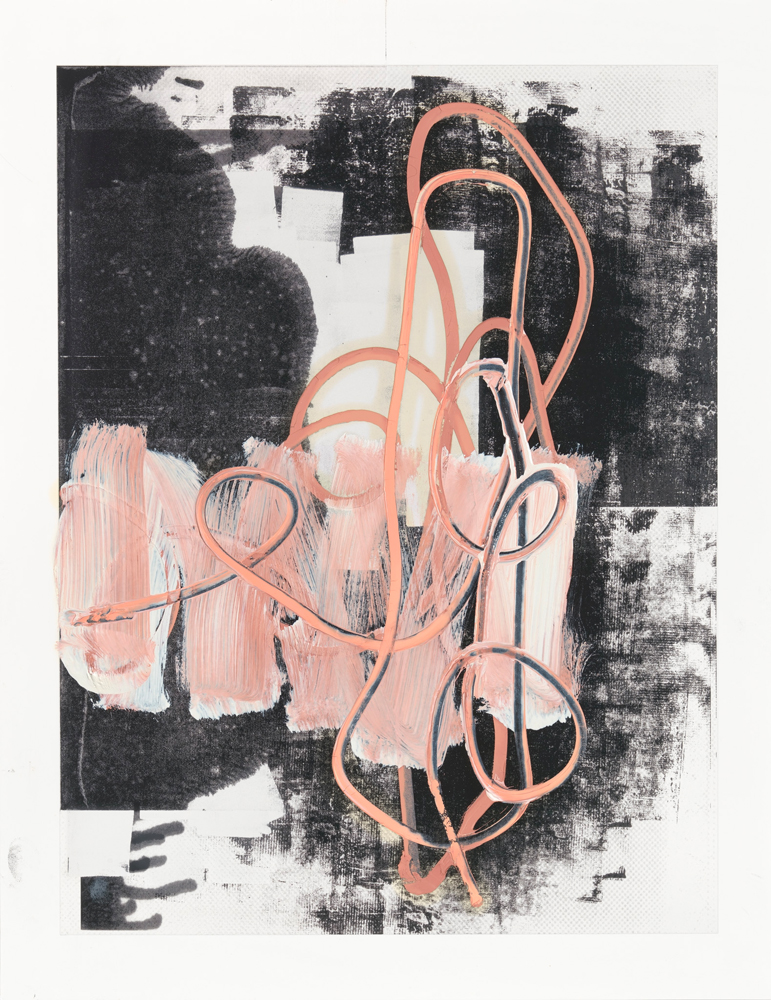

“I have left all the welts, so you can see the process of assembling,” you said. To me that’s like silkscreen, where you can see it’s handmade, but it’s a mechanical hand.

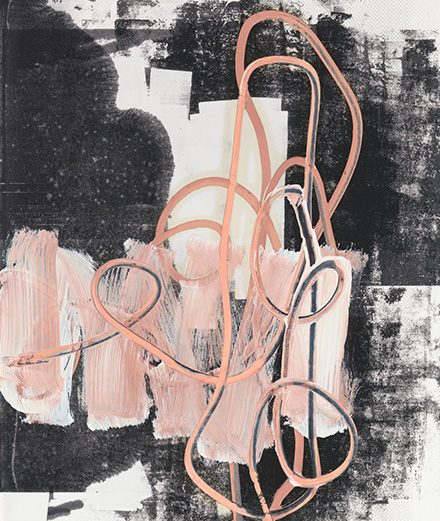

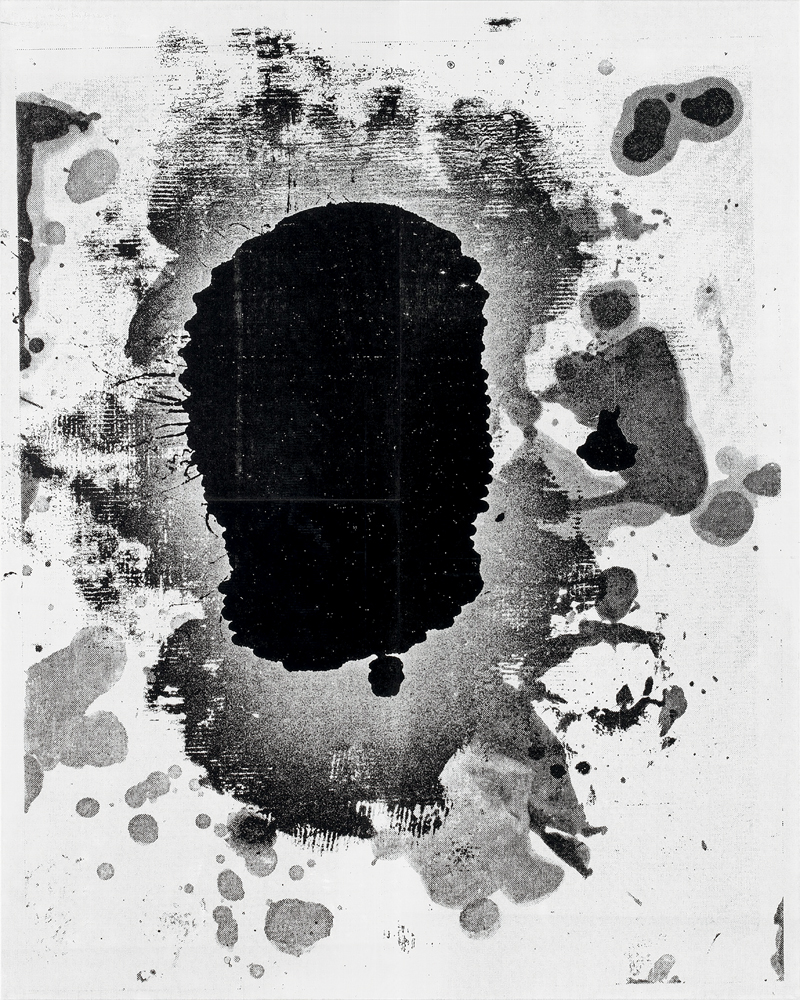

I use silkscreen like a brush. It’s just something between my hand and the painting. I do the screening myself and it seems like a very mechanical process. We know from early Warhol that there is an expressive way of working the silk- screen, so I have some control when I’m making the painting – density, focus, all kinds of things. To me, it’s one of those kinds of process that you can see, like a dripping in the painting, you can see it, you can feel that it is handmade. You know that it is not completely mechanical, it’s printed like a professional printer. I think that gives the audience an entrance into the painting. I think visual art has power, that’s the interest to me, and that should communicate to the audience. It’s not a specific message.

You’ve been working on some pieces for several years, coming back to them, using different techniques, scanning them, painting them, photographing them. When do you feel the work is finally finished?

Oh, that’s the million-dollar question! That’s the hard part. I think, with experience, I trust myself, so I can do it a little easier. But I’m always looking for something different and new, and I don’t know what that is until it happens in the painting. So that’s the challenge – to figure out how to finish the painting, and what it’s going to say. I used to work with Polaroids in the studio, and take lots of photos so that I could see where I was. I’ve kept all these photos in a box for ten years now. Looking over them, it was interesting to see all the paintings that got painted over, and all the paintings that weren’t “finished paintings” and probably should have been. I think, as opposed to the high idea of Modernism, there isn’t one particular perfect painting that you’re looking for. All kinds of different things can happen and be interesting. That’s the exciting part!