12

12

Interview with Lee Ufan, the living legend of contemporary art

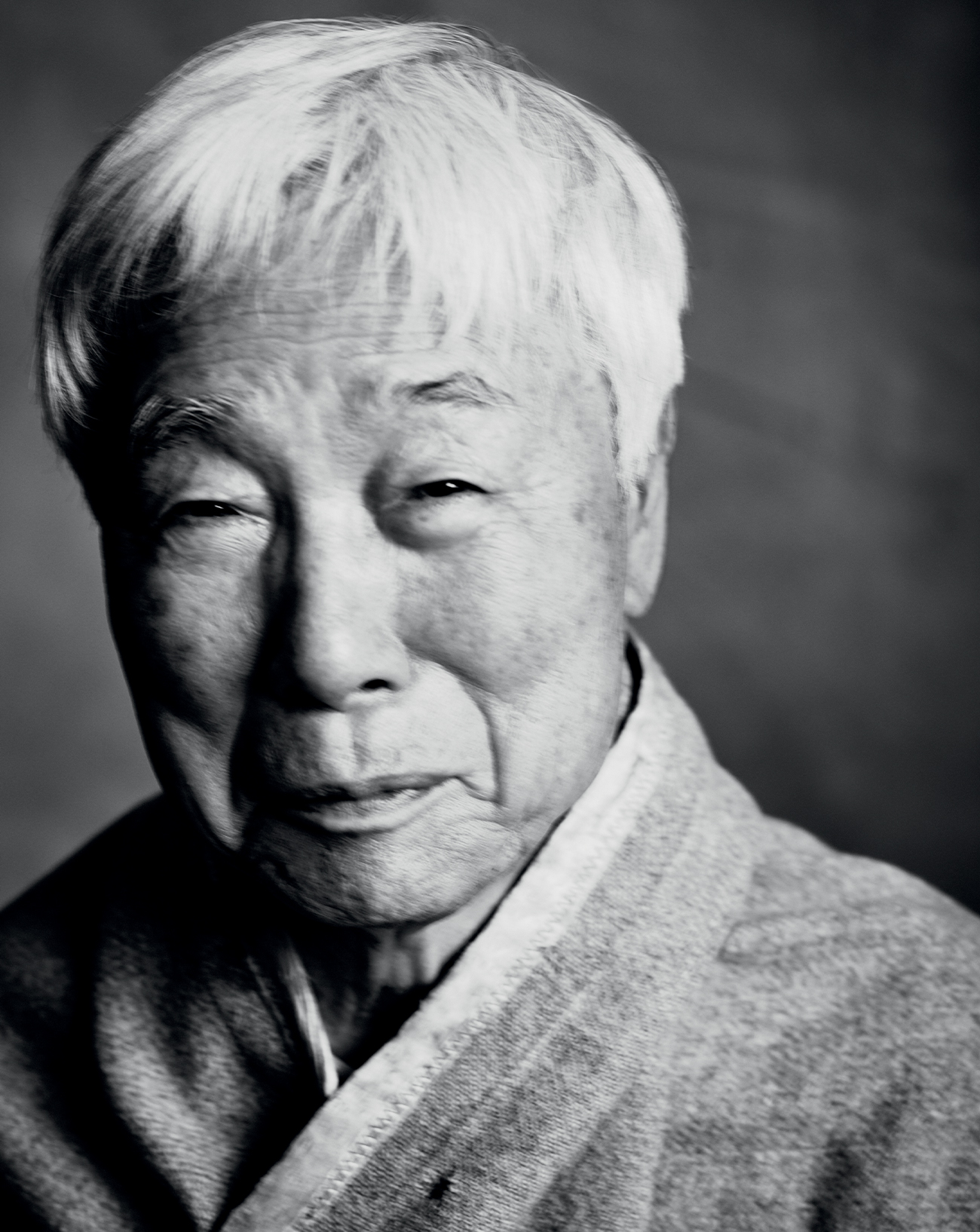

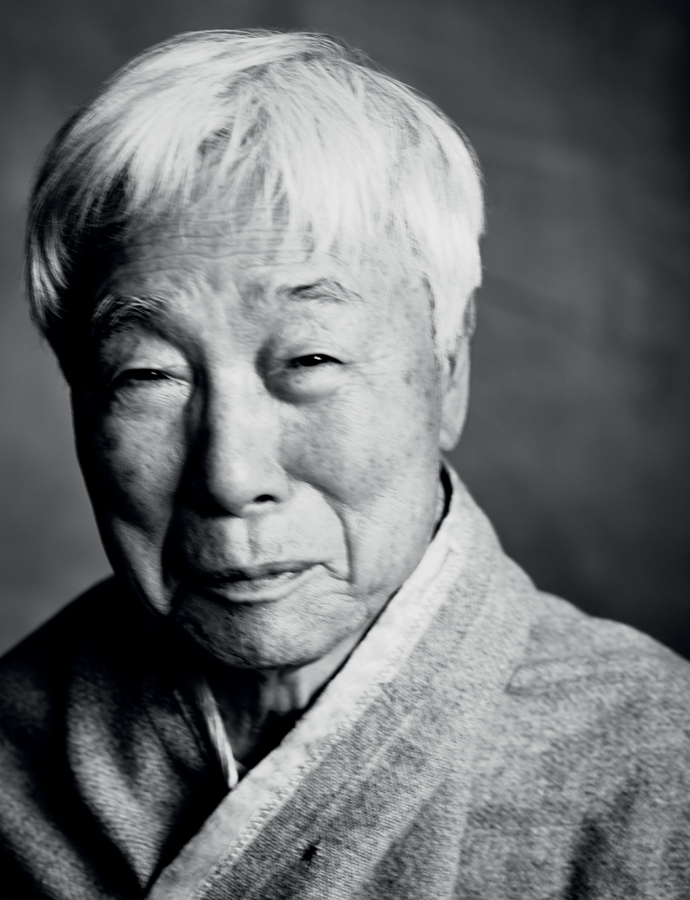

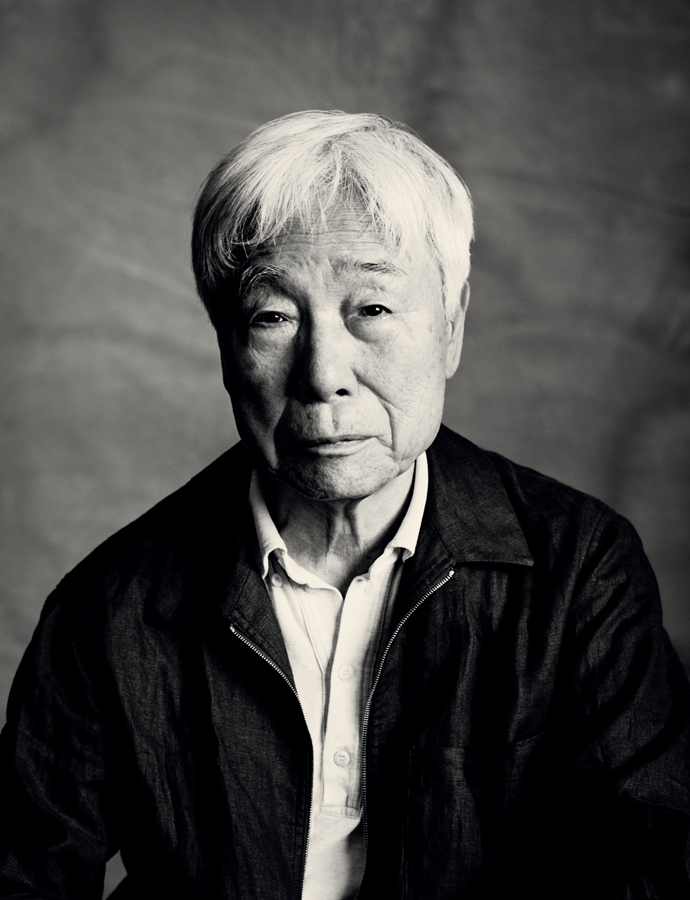

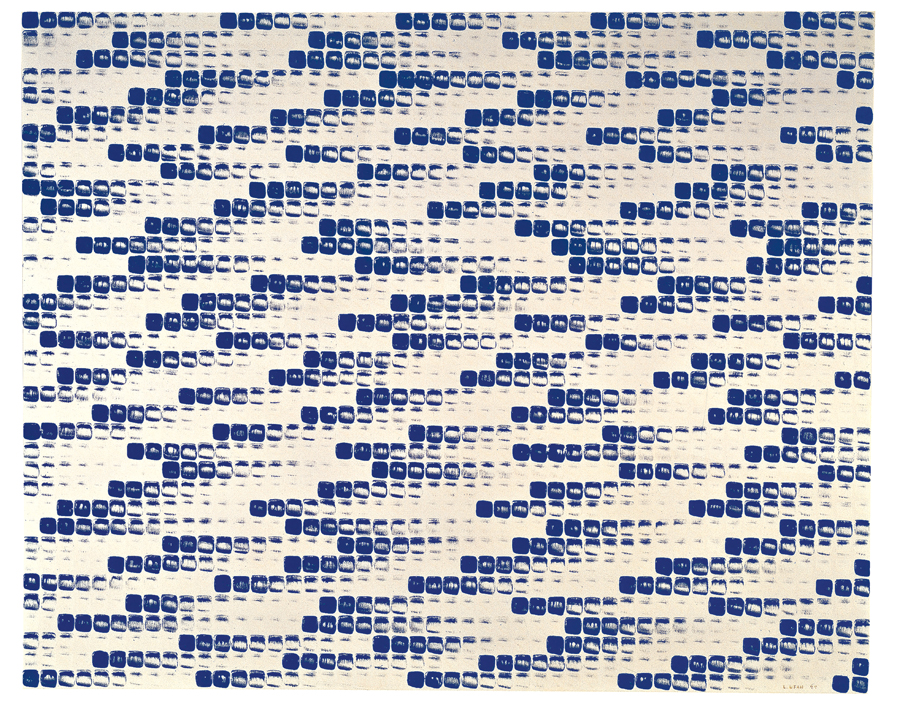

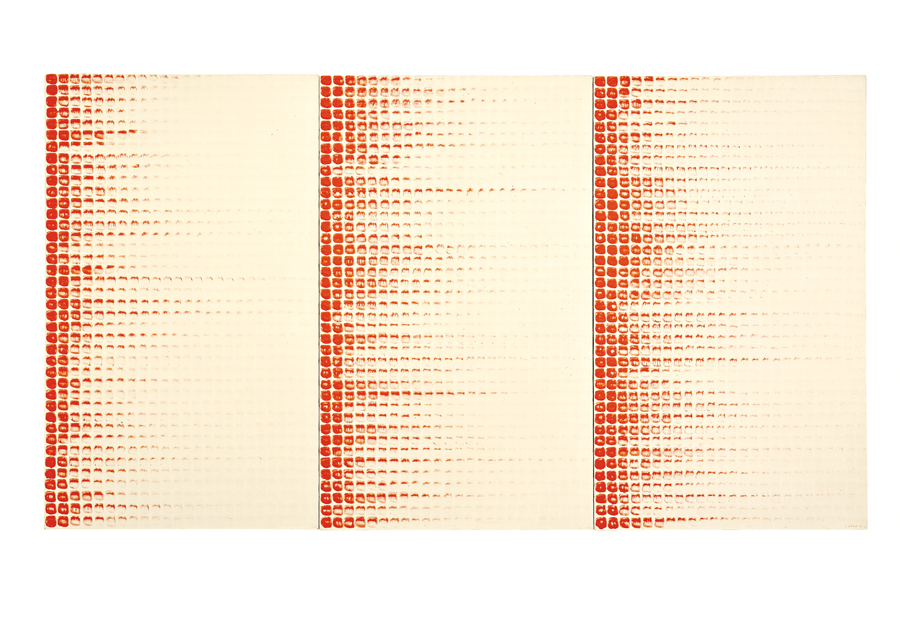

At almost 90, Lee Ufan is one of the most respected figures in the art world today. A painter, sculptor, theorist, and philosopher, he has been developing his very personal minimalist vocabulary since the 1960s. Simple components, chosen for their materiality (stones, sheet steel, iron bars, mirrors, paint pigment, etc.), are set in relation not only to each other but also to the space around them and to the viewer. The same goes for his paintings, whose emblematic touch consists of a flared square whose width is that of the brush he wielded with such extreme control and concentration. Numéro art met up with him in Paris, at his atelier, and afterwards at the studio of another great master, photographer Paolo Roversi, who took his portrait.

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok,

portraits by Paolo Roversi.

Numéro art 17 is available at newsstands and on iPad since October 18th, 2025.

Lee Ufan: A major figure in contemporary art

Lee Ufan was born in 1936 in Korea, but it was in Japan, where he moved in 1956 to study philosophy, that he rose to prominence as an artist, becoming a central figure in the Mono-ha (“School of Things”) movement. From the outset, Ufan viewed painting and sculpture as complementary practices. In the 1970s, his paintings explored the flow of time, repetition, and difference, in pursuit of infinity – in his practice, painting becomes an act of “concentration, breathing deeply and steadily to allow the organic forces of thought, hand, brush, colour, canvas, air, and time to come together.”

“Ufan’s work is above all an experience of space and tension revealed, between inside and out.” – Lee Ufan

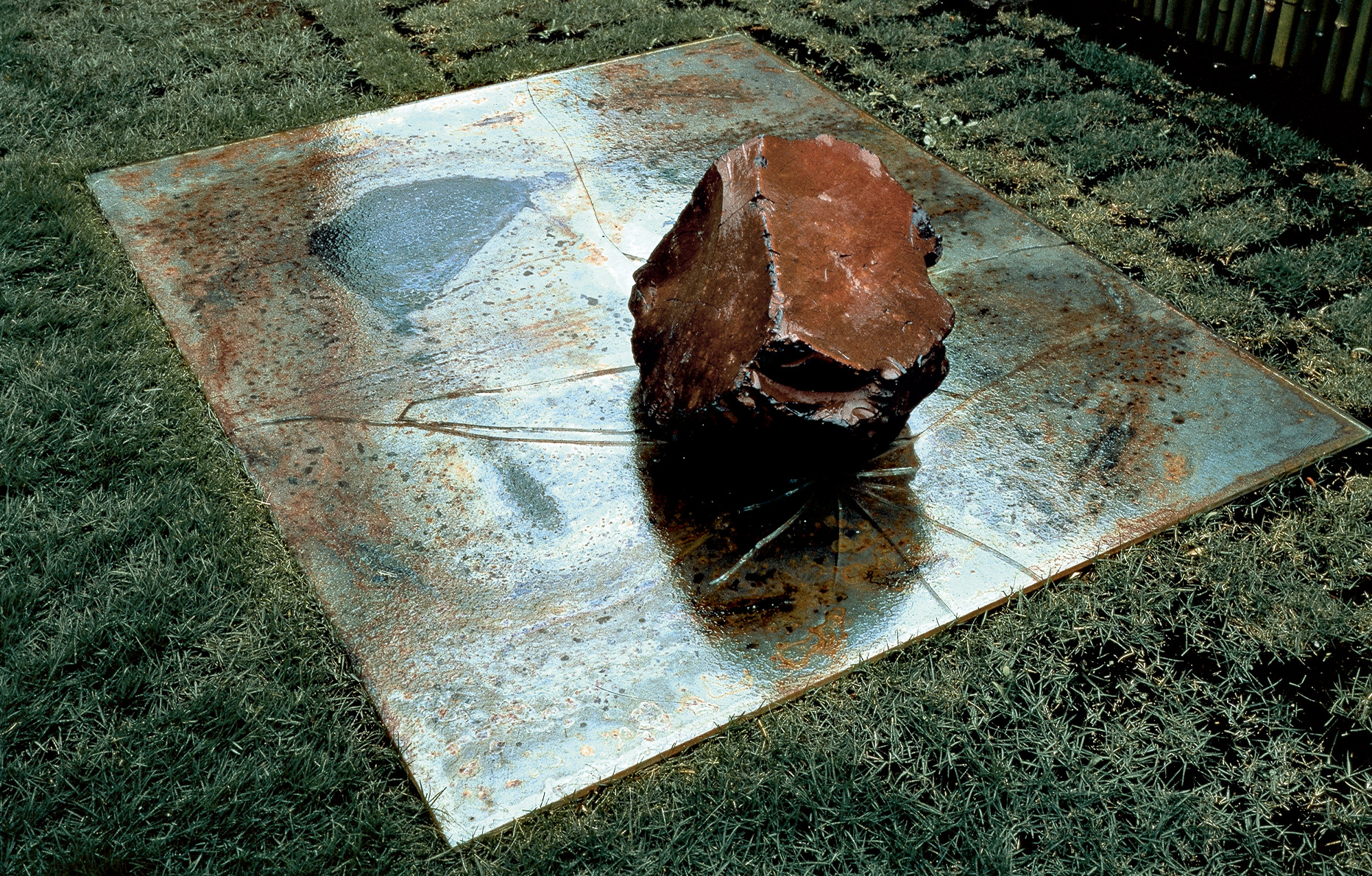

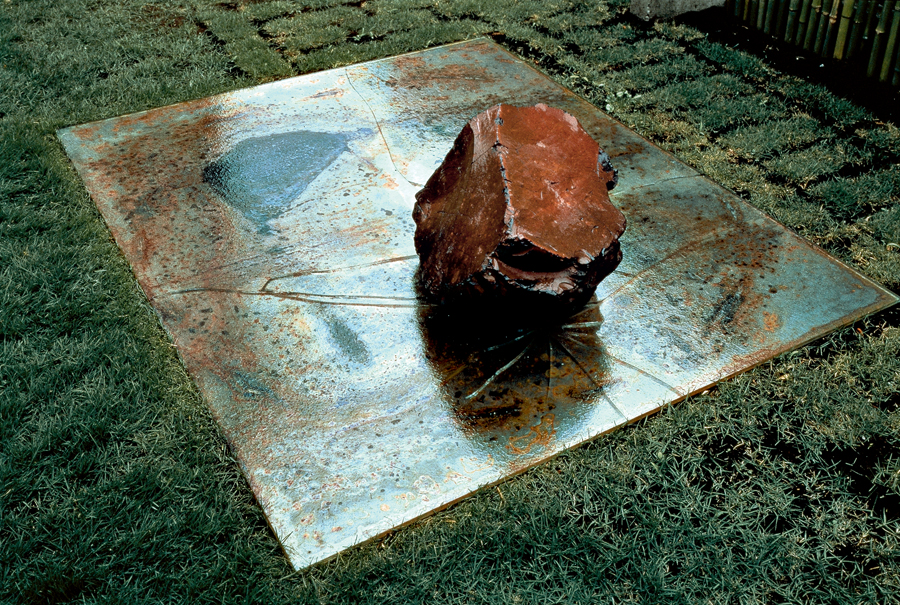

The canvases in his series From Point and From Line, for example, deploy rhythmic gestures, like breathing. In the 1980s, with his series From Winds and With Winds, Lee Ufan gave yet more space to the uncontrolled, while in the 2000s his Correspondence and Dialogue series radically reduced and concentrated the visible traces of his hand, the brushstrokes establishing a tension between themselves, with sometimes just one that entered into dialogue with the blank surface of the canvas. In his Relatum – the Latin for “relation” – series of sculptures, this interplay between space and related elements is yet further highlighted. Indeed, Lee Ufan’s work is above all an experience of space and tension revealed, between inside and out.

Interview with artist Lee Ufan for Numéro art

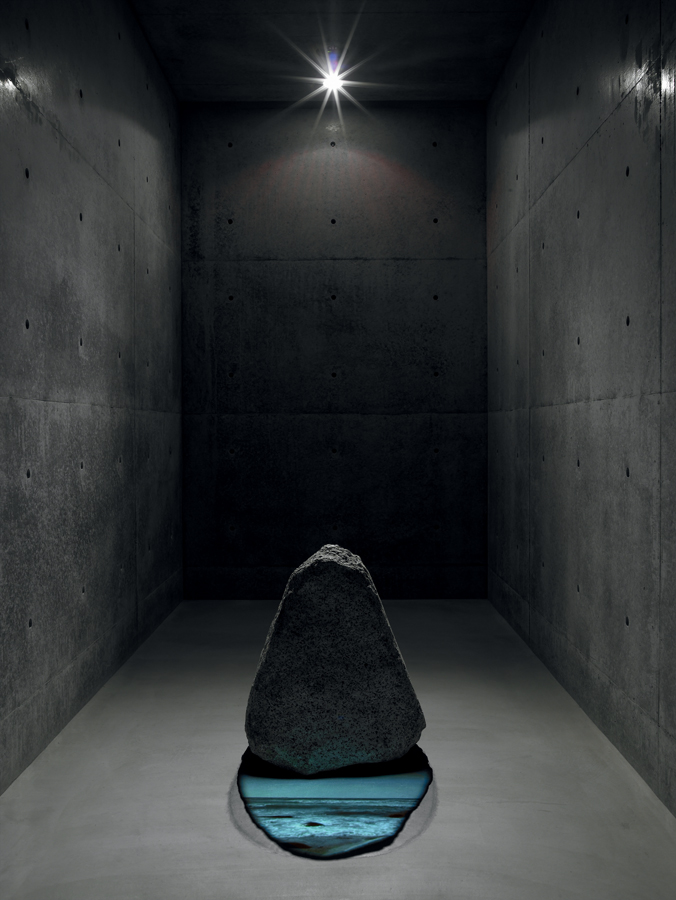

Numéro art: Your work can be found in many museums, in the Pinault Collection’s current hang, as well as at art fairs. But your museum on the island of Naoshima in Japan is perhaps the place where your work can best be understood. What does Naoshima represent for you? Lee Ufan: Naoshima is first and foremost the project of a great Japanese art collector, Soichiro Fukutake, who, in the late 1980s, had the visionary idea of transforming the abandoned land he had inherited on the island into a place dedicated entirely to art. He turned to Japanese architect Tadao Ando to build a complex of museums and hotels. The island was completely revitalized, and people from all over the world now go to see it. It’s a rather mysterious phenomenon. Art there is in direct dialogue with nature. You really have to take your time.

“Human beings are animated by life, by the vital force of the living. This connects us to the cosmos at a far greater scale.” – Lee Ufan

On Naoshima, contemporary art is an experience, an encounter with something unknown. Ando was pivotal in that. He’s often reduced to his use of concrete, without seeing what he actually does with it. When building a concrete wall in a space, he seeks neither to freeze nor to enclose it. Rather, he creates tension in the space, making it somehow move. Which means that an empty space no one had noticed before suddenly becomes visible. Naturally it was with him that I created my museum in Naoshima.

Could this way of engaging with space also apply to your own work? I’m thinking of the idea of tension created in a space – a canvas, a gallery – or the creation of tension between different objects, whether natural or industrial. You’ve understood our approach perfectly. That’s why, for me, the museum in Naoshima couldn’t be just another museum. I wanted to create a space that, like a cave, had existed since the dawn of time. You enter it like entering a mother’s womb. It’s a space that invites meditation. But I believe your question also alludes to the nature of my work. The way I make art never involves sitting cogitating at a desk. I always start from the space, seeking a dialogue. I don’t start from an object, nor is my goal to create one. Instead, I aim to bring forth a space and make it more conducive to dialogue. In Naoshima, this space evokes a cave. It invites a dialogue with oneself and with the universe. You enter it as if in resonance.

Is there a place for beauty in your work? Does the concept interest you at all? I studied philosophy in my youth, and read many books on aesthetics, so beauty is something I generally keep in mind. In contemporary art, the concept has been more or less rejected, particularly the Romantic ideal of beauty, which centred almost exclusively on the human being seen through the human gaze. Barnett Newman, for instance, preferred the term sublime [The Sublime is Now, 1948]. He sought to capture the sublime on canvas, to prove its existence. The idea is interesting, but I don’t share his approach. Moreover, the sublime is a part of beauty. In truth, I can neither categorically deny the notion of beauty nor assert its importance. Beauty has been part of our daily lives since time immemorial.

“The way I make art never involves sitting cogitating at a desk. I always start from the space, seeking a dialogue.” – Lee Ufan

We want to be beautiful, we take pride in how we look. The sense of beauty is inseparable from being human. But if we go back to primitive times, the experience of beauty was tied to nature in all its vastness. Today, however, the rise of artificial intelligence and digital data reduces the possibility of such experiences. Human beings are animated by life, by the vital force of the living. This connects us to the cosmos at a far greater scale. In this context, humanity is a mere grain of sand. We cannot be at the centre. Such questions cannot be dismissed, and we should continue to ponder beauty not as an answer, but as an ongoing enquiry, a perpetual quest. That’s my conviction.

You seem very critical of modernity’s tendency to place humankind at the centre of the world. Modernity can be interpreted in different ways. But adhering to it as an object constructed around our ego, the human ego, has, I believe, prevented us from understanding the essential relationship between inside and out. By focusing on the human ego, we no longer saw what surrounded us. But I think this approach was reduced to nothing after World War II. It’s essential to create a dialogue between what’s known and unknown.

“We should continue to ponder beauty not as an answer, but as an ongoing enquiry, a perpetual quest. That’s my conviction.” – Lee Ufan

The incomprehensible nature of things is essential. That’s why I told you I don’t create my works sitting at a desk. A work of art cannot be a pure inner reflection of my mind. Art is made in a specific place, in dialogue with the exterior. It weaves things and spaces together with connections and associations. My body also plays a role in bringing things into being. I am present in the space when I create, which allows me to welcome everything that’s there, and to create dialogues.

How, for example, did your Relatum series come to be? Naturally, I search for stones in quarries. But I’m not looking for beautiful stones. Some may inspire me, it’s true, they say something to me. But that’s quite rare. What’s important is space. I choose each stone in relation to the space. A stone of a certain size will be paired with a metal plate of a certain size. This dialogue between industrial society and nature creates a resonance. That relationship is essential because it’s what allows us to feel something stronger, something that was hitherto incomprehensible. And this only makes sense in a specific place.

“I always feel a mysterious force emanating from these stones. An absolute presence.” – Lee Ufan

I’ve been using stone in my work since the second half of the 1960s. My viewpoint has evolved, and yet something remains unchanged. Like when I visit Brittany or England and come across dolmens or menhirs – I always feel a mysterious force emanating from these stones. An absolute presence. It’s not just a block of stone – it’s something sublime, something beyond comprehension. These stones existed long before humanity. They are a fundamental, primordial material that humans have always needed to use, especially in art.

And how do you make your paintings? When I paint, sometimes I position my canvases on the wall, at others on the floor. They become a screen, a predetermined space. Something happens when I stand before the canvas and exert my full physical strength. Each of my gestures – a dot or a line made with the brush – is an opportunity to create a new vibration, new sensations.