27

27

Hyper sensations : diving in P. Staff’s work

This autumn, after their sublime video On Venus was screened at the Venice Biennale, the artist is exhibiting a mysterious series featuring knives at Paris’s Sultana Gallery.

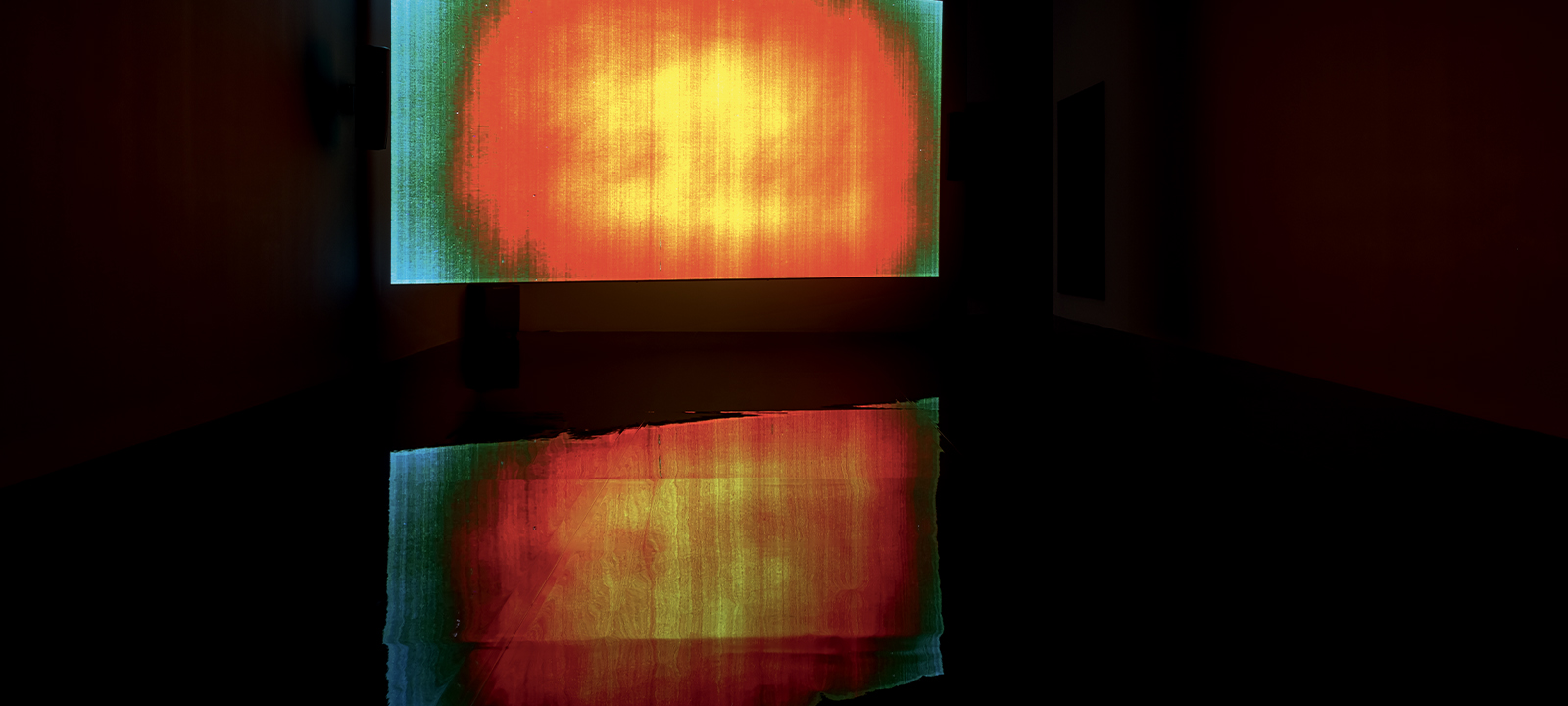

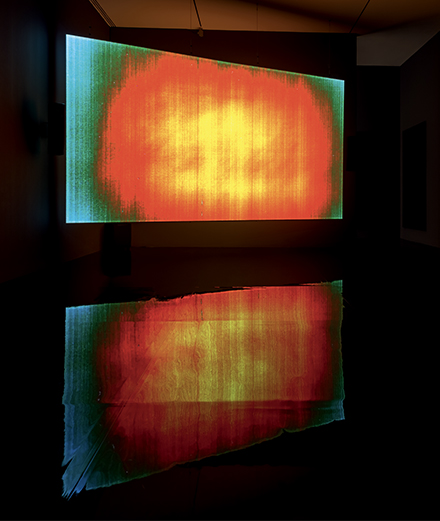

I’ll start with an oversimplification: language is a key component in nearly all P. Staff’s artworks. Poetry lines the lower half of the screen in On Venus (2019), a space usually reserved for subtitles, though here, since there is no speech, the words feel like an act of telepathy, translating the silent planetary language of the sun. In other works, such as Depollute (2018), text fully engulfs the frame, like a series of title cards with tender medical instructions to perform a self-orchidectomy, each step flashing rapidly, confidently, on screen. In Bathing (2018), words overlay the image of a person, dripping wet and dancing wildly in an empty industrial space; here the text is stretched, letters strewn across the moving image like dismembered appendages, dissected into delicate and gory parts.

Here’s the oversimplification: Staff’s writing – and by extension their images, moving or still – articulate the sensations of a body, and that body’s relationship to others, through sensuous, visceral images; descriptions of fluids exchanged, of pressure applied; descriptions of pleasure, pain, discomfort, relief, death, and desire. In several interviews, Staff describes their body as a lens through which they make their work. One practical example of this is videos that are edited to the rhythm of their breath, with cuts made at natural blinking points. Their idea is to translate their own somatic experience of the world into a visual artefact. The undergirding promise of this work, however, is not to decode, or perform the experience of their queer and trans body for an audience, but rather to map the hypersensuality of a trans body into a work, into a viewer. In a text Staff shared with me last month, the scholar Eva Hayward likens the trans body to that of a spider, whose small parts are covered in thin hairs that sense every slight change in wind direction and temperature. Hayward draws an analogous hyper-sensitivity in the transitioning body, whose experiences may include heightened ocular and haptic senses resulting from hormonal treatments. In Staff’s work, a body in transition – through hormones, surgery, or the experience of dysphoria – is liminal, porous, leaking into the world all the while letting it in. These vulnerabilities, this fluidity, are not weaknesses, but rather what makes the trans body highly discerning.

Staff is often misconstrued as a video artist, when in fact they have a deeply promiscuous relationship to the materials they use (film, video, photography, resin, holograms and existing texts). They are unprecious about each medium in their toolkit, and their works often result in an estrangement from the material. A video image is likely to be digitally coated with the viscosity of film solvents, photographs are drowned in resin, familiar sounds are divorced from their source. This perversion also applies to other people’s stories within Staff’s work: an autobiography, a play, a theory. In this slippery space, the personal or the proprietary is un- tenable, as is the case in Weed Killer (2017), where Staff recontextualizes scholar Catherine Lord’s recounting of her cancer and chemotherapy, likening it to transition.

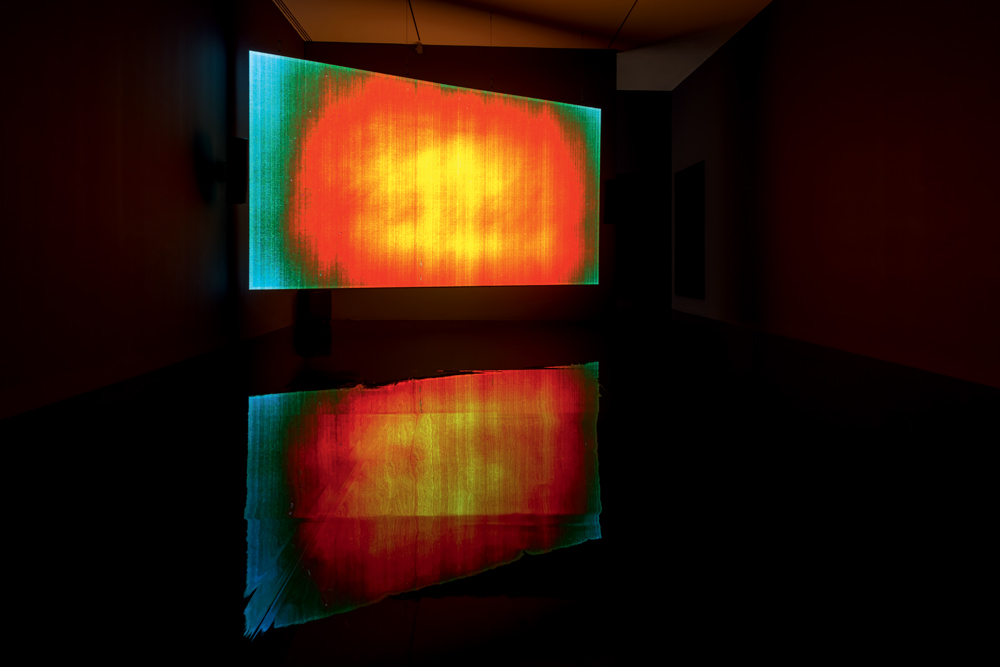

Here, experience is a collective material. The exhibition itself is also treated as a medium, with careful scenography that choreographs the viewer from one room into the next, pulled by sound, light or their joint absences. A prime example is the original installation of On Venus at the Serpentine Gallery in 2019, which began with the experience of the video: a mix of bright, colourful images depicting the sun juxtaposed with the skinning of a snake, animals walking to their slaughter and the extraction of hormones from mares. The images were both stunning and assaulting; the viewer was complicit in the violence on screen, yet safely removed from it in the gallery. But when the video went silent, the viewer became aware of a slow dripping sound in the space around them – Staff had lined the building’s piping with a mix of corporeal and chemical acid dripping into designated containers. The viewer’s body now contained its own visceral relationship to threat, the exhibition acting like a living organism, a parasite overtaking the architecture of its host institution.

This way of animating the “dead thing” that is a building, a structure, an institution, is a way of pointing at it, making it visible. So actually, instead of decoding their own body in their work, Staff is decoding institutions and the oppressive structures they represent, the structures that “foreclose” bodies, to use their own terminology. In this way, Staff’s work is also about “the slow violence of institutions,” to quote British filmmaker Sandra Lahire. Staff recently co-hosted a screening of Lahire’s trilogy Nuclear Film in Los Angeles: in their introduction, Staff created links between the various poisons that permeate their and Lahire’s work. Nuclear power, chemo, and hormones are both a solution and a threat. The societal structures that regulate and dispense the poisons loom large, but so do the bodies that reappropriate them for other purposes.

P. Staff’s artworks are not moral ; they say that “desire is ungovernable”.

Some of the stakes in Staff’s work seem to recast the queer behaviors that are commonly prejudiced – read as socially harmful – and convey them as pleasure-filled, all the while exposing the institutions that promote the marginalization of queer bodies as well as fixed ideas of desire —the oft-in- visible kind of moralizing that it is taken as fact. Staff’s work uncomfortably refracts the visibility and decoding that institutions demand of queer bodies onto themselves. In a sentence that stays with me from P. Staff’s 2019 work The Prince of Homburg – a fragmentary video restaging of a play on the revolutionary potential of dreams and ideas of discipline – former lawyer, trans activist, and veteran Debra Soshoux defines the law as “a consensus of a body politic at any given time.” This understanding of society as a corpus – and the malleability of the structures we commonly understand as fixed in society – feels like a key to Staff’s work.

Staff’s work is defined by the feeling of a push/pull. The things you want to look away from in their work (cattle walking to their massacre, a snake twitching to death, men pissing into their own mouths) are what hold your gaze. Some of the images are grotesque, many of the ideas are uncomfortable and unresolved, all of them are erotic. Lush images, rich colours, sophisticated typography – they seduce. Through their contradictions, these works find the eros of discomfort, displeasure, “dis-ease.” In interviews, Staff will acknowledge that it is complicated to liken illness and transness, but their works are not, and do not aim be to be, moral. They are actually about “the ungovernability of desire.” The works, like most things, are unreliable, volatile, and aim to betray the viewers’ comfort. They are about and comprised of “wrongness,” given society’s application of a label of “wrong” to queer-centered bodies and desires. Queerness is like a substance that cannot be contained, no matter how hard a rigid apparatus may try. In talking about On Venus, Staff will describe it as “conjuring a state of near-death that has parallels with trying to survive as a queer person in a heteronormative world.” A sensation of anxiety, pressure, dysphoria.

The apparent (and productive) contradiction in their work is that they identify misalignments as a form of suffering, and then later, identify suffering as a form of pleasure. The knives, blades and handles shown on these pages are here to remind you that sometimes what hurts also heals, that euphoria can disappoint you, and that dysphoria can be the catalyst to transformation. Or maybe they are not here to transmit any of that; they don’t need you to know. They are here to glow, to lend imprinted light to the photographic page. Their rich colours are a reminder of the colours you are made of, that the inside of the human body contains infinitely bright hues that transform upon making contact with air. Each sharp tool here also belongs to someone. They are portraits, psychic X-rays of an object, of simultaneous harm and care.