14

14

From Paris to Avignon: Jean-Michel Othoniel, a spellbinding artist

An exceptional guest of honour in Avignon this summer, Jean-Michel Othoniel has transformed no less than ten emblematic sites, from the Palais des Papes to the Church of the Jesuits. An enchanting journey through the French artist’s paintings and sculptures, the result is a triumph of glass, light, and colour.

Text by Colin Lemoine ,

portraits by Jonathan Llense.

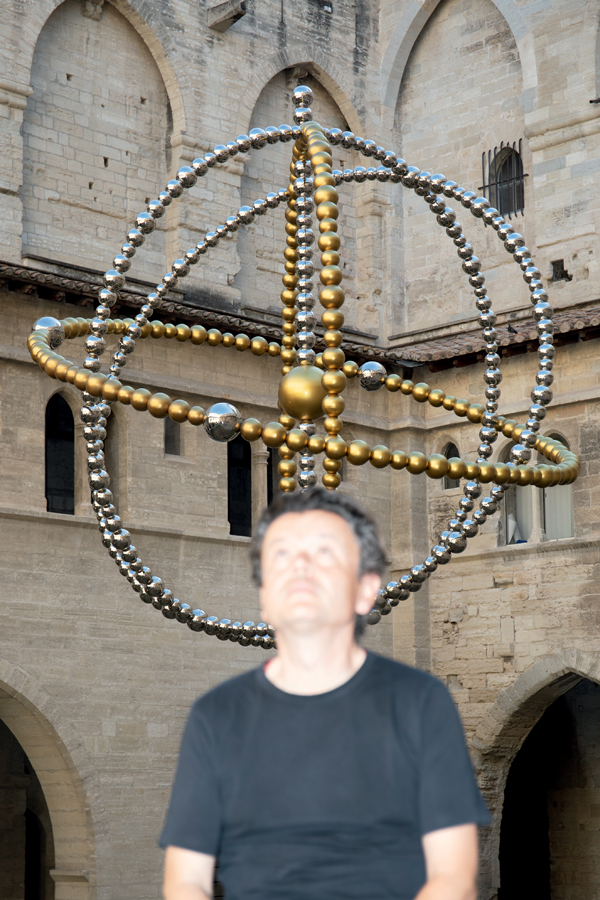

Jean-Michel Othoniel in front of L’Astrolabe in the cloister of the Palais des Papes. Portrait by Jonathan LLense for Numéro art.

Jean-Michel Othoniel in Avignon: A historic exhibition

It’s always intimidating playing a piano duet, hearing nearby octaves magically entwined with the music you yourself are making, seeing, near your own, ten foreign but euphonious fingers. When Jean-Michel Othoniel handed me the rather daunting score, it was a question of Avignon, of the Rhône, of grandeur, of Petrarch and Laura (the former so in love with the latter), of an impossible and perhaps improbable love (but truth doesn’t give a fig for authenticity), of palaces, popes, a bridge, chapels, the sun’s blonde glow, and the sparkle of glass; of phantoms and fantasies; of the sailor’s monument, so beautiful one could weep; of childhood and of what childhood infuses with eternal lightness in the heavy hearts of men; of secrets and silences; of scarlet sharp notes and powdery flat tones, and of that slightly crazy word that trickles over from holding three intensely liquid vowels within its belly – beauty. Beauty, with the water of poets and the architect’s T-square.

Beauty, that exact geometry which is orthogonal to joy. Beauty as an ancient watchword, a talisman that is still brandished by madmen, children, and artists. “Come, it will be beautiful” – such was, crazy and inaudible, the true slogan, the programmatic motto of this project, the political slogan, the motto that is now unpronounceable in certain capitals and under certain capitols, the true phrase because it is pure loss, because it is contrary to the law of figures, to the diktats of an eye for an eye, and to the dominance of the strongest, that insane phrase that Petrarch must have uttered on 6 April 1327, on that warm, cherry-flavoured day when, for the first time, his unmirrored gaze fell on Laura’s glorious body. A body like an apparition or a spectre – which are the worst, because they’re unbreakable.

A poetic journey across ten iconic locations

“Come, it will be beautiful,” Jean-Michel Othoniel said, handing me the score. We talked, closed our eyes in Paris, and opened them again in Avignon, in winter, beneath the bare plane trees, and saw the empty promised spaces, fallow, waiting, when the future is conditional. We told ourselves it would be beautiful if and it would be beautiful when, we opened doors and horizons, climbed steps, touched damp stone, imagined pearls and bricks, divined the future, augured, inaugurated, and silently sight-read the first score, the one that trembles, burns, and stutters. Then, now in tune, we at last played – he with colours and I with phrases – to form a text, an etymological fabric, weaving together our wishes and mingling our gestures. His watercolour, my ink. It was beautiful. Past tense.

“Come, it will be even more beautiful,” Jean-Michel told me on the phone. Published by Actes Sud, our velvety volume, Cosmos ou les Fantômes de l’Amour, is a sketchbook: it is filled with words, colours, lines, and wishes. It fuelled my desire to see it in real life – for real, as kids say when they seek to play adult-sized games. I wanted to see this planar beauty, hitherto confined to paper, come to life in space, see the score amplified by a third dimension, by the depth that transforms planes into volumes; I wanted to dive into reality, into this axonometric world where our real bodies circulate. Train, heat wave, crowds.

Avignon, then. Since this maze-like city rejects any form of coercion, Jean-Michel Othoniel plays with the tangle of streets, deploying a a diffracted, prismatic Map of Tendre so that each constellation in this cosmos can be observed in a thousand different ways, like the Great Bear which, on summer evenings, hides, reverses, or reappears depending whether the moon is full or gibbous, the clouds of ether or lead, our hands bound or unbound. And the Avignon night now offers precisely that: on the façade of the Jesuits’ church, today a museum of stone carvings, monoliths of sulfurized glass, set within vertiginous recesses, form celestial monuments, like the fireflies or shooting stars that, on these same summer evenings, get caught in the silver-studded canvas of the Great Bear, as if to remind us that wide-eyed dreams abolish both the near and the distant.

The city transformed, from the Alyscamps to the Requien Museum

In the morning, once the dream has dissipated, the church’s choir delivers a secular liturgy: everywhere bricks dialogue with steles, altars, fragments of antiquity, scattered bits of the past, and broken tombs, as though the Alyscamps were contained beneath a giant marquee whose central pole is a gigantic mastaba of gold and caramel bricks, a wailing wall on which to mourn the deceased and the beloved, the lost or the adored, adored because they are lost. The colour of amber with the sweetness of incense, Precious Stonewall, which was made in India, is a monumental amulet and a maharaja’s jewel.

At the Pommer Baths, the three vowels flow, the water of life sings, springing from glass geysers nestled in half-open cabins, like mouths of truth or fountains of childhood or youth. And this luxury is a joyful delta, a Ganges in which to bathe, abandon ourselves, and purify our corrupt and weary hearts, when the music adds a note hitherto inaudible on paper, an emollient note that is a caress and the continuous flow of lovers.

At the Muséum Requien we find the herbariums made by Jean-Michel, that Saint Francis who speaks to flowers, that Pasolinian archangel who knows by heart the spells cast by lilies, chrysanthemums, and roses, who saturates the cramped space – barely as big as a sacristy – with display cases as profuse as greenhouses and as mischievous foliage, one of which informs me that Lunaria annua is called monnaie-du-pape in French.

Works that open a conversation with history

Erotic language scorns literalism: it loves only literature. Symbolization. It takes a Palais des Papes to get the measure of this operatic machine in glass, steel, brick, pearl, serpentine consonants, and aspirated vowels. The astrolabe in the cloister, whose gold exalts that of the distant Virgin of Notre-Dame-des-Doms, reveals the melodic line of a score that knows nothing of hydroponics and grafts that won’t take; everything here is designed to embrace the sovereignty of the place, to repair and suture, like the Japanese art of kintsugi.

Each of Othoniel’s works is an epiphany that tears apart the austere veil of the past, that forces us to see differently the rib vaults, the ancient frescoes, and the soaring magnificence of the great chapel, which reminds us that, as in the Piombi in Venice, people loved, adored, dissimulated, and spoke a secret language that sanctified opulent beauty. I witnessed this: hordes of visitors slowing their leisurely pace during an otherwise dull visit, rubbing their eyes, breathing through gaping mouths as though they were watching fireworks or standing in the Sistine Chapel, caught up in billows of that never-exhausted emotion – wonder.

Jean-Michel Othoniel at the entrance of the Palais des Papes. Portrait by Jonathan LLense for Numéro art.

A minimalist gesture at the Collection Lambert

Love leaves its mark, good or bad, semen or blood, blood or flesh. The Saint-Bénezet Bridge, the Petit Palais Museum, and the Sainte-Claire Chapel, where Laura appeared to Francesco, offer pearlized treasures, diaphanous halos, and hearts laid bare, the scattered traces of love that has flown, the glittering fragments of a lover’s words, and the cosmic dust of stars that are said to be shooting.

But it is perhaps at the Collection Lambert that Jean-Michel, as a surveyor of passions, is at his most enchantingly implacable. In dialogue with Donald Judd, Robert Ryman, and Sol LeWitt, he plays a sublime, minimalist, almost dodecaphonic score that dissociates the merveilleux from the baroque, separates grandeur from pomp, and uncouples luxury from ostentation. With cardinal assurance, this exhibition is the splendid culmination of the artist’s entire oeuvre, which is obsessed with the brilliance of simplicity – that simplicity which makes beautiful the Great Bear, la petite mort, and the rosy-pink peony.

Come, it will be beautiful.

“OTHONIEL COSMOS or the Ghosts of Love”, on view until January 4th, 2026, across ten iconic locations in the city of Avignon: the Palais des Papes, the Pont d’Avignon, the Petit Palais–Louvre Museum in Avignon, the Calvet Museum, the Requien Museum, the Lapidary Museum, the Sainte-Claire Convent, the Pommer Baths, the Collection Lambert, and the Place du Palais.

“Jean-Michel Othoniel. New Works”, exhibition open until December 20th, 2025, at Galerie Perrotin, Paris 3rd.