14

14

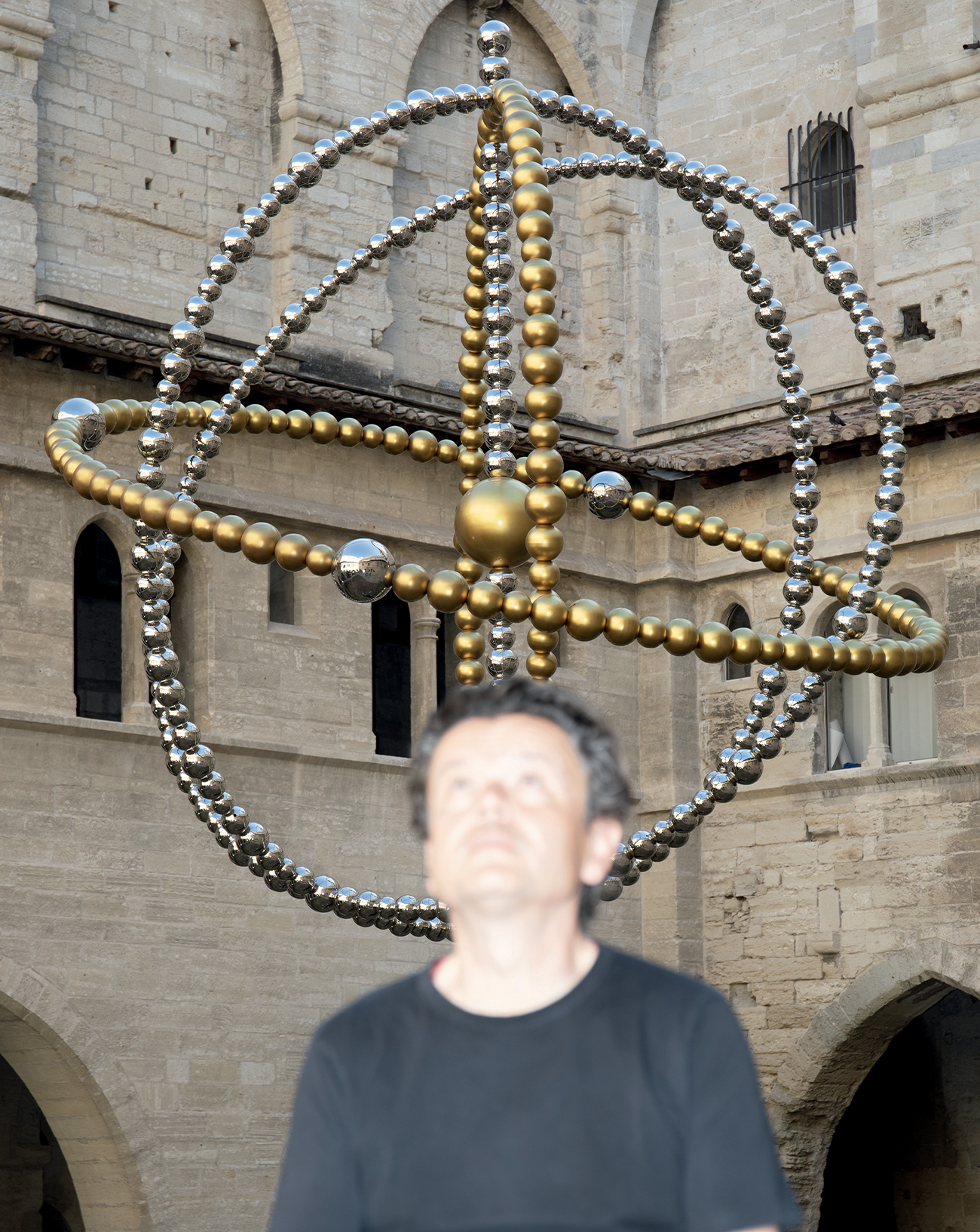

Artist Cyprien Gaillard : “Building in ruins is like going without sleep or having a fever”

A major figure in the international contemporary art scene, winner of the 2011 Marcel Duchamp prize, Cyprien Gaillard was back in his native France with a double exhibition at Paris’s Lafayette Anticipations and Palais de Tokyo presented in the Fall. For Numéro art, he sat down with the shows’ curator, Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel.

Portraits by Marc Asekhame,

Interview by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel.

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel: For HumptyDumpty, your double exhibition in Paris, you crisscrossed the city photographing the areas around the Eiffel Tower, the Concorde and other monuments currently being renovated ahead of the 2024 Olympic Games.

Cyprien Gaillard: The way cities try to preserve certain buildings has always interested me. Restoration policies are inevitably exclusive – you can’t preserve everything. There’s a hierarchy that defines which buildings and monuments take priority. These are the limits I want to explore – I’ve always been interested in fault lines. I’m old enough to remember playing marbles – you had to get the marble into a hole. For me, cracks in the ground are a space to aim for, to occupy. The theme of interstices often comes up in my work… I think every artist seeks an entry point into the world around them, a breach through which light can shine. In our increasingly rationalized, standardized cityscapes there’s less and less free space in which to project oneself or to experience anything other than oneself…

The HumptyDumpty project is an exhibition in two chapters, with an echo and resonance between the Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations.

HumptyDumpty refers to a character in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. He first appeared in an 18th-century nursery rhyme, and was perhaps also the name of a cannon. In Carroll’s book, Humpty Dumpty is an egg who lives on a brick wall. One day, he falls off and breaks. A group effort is made to put him back together, but, as the nursery rhyme explains, it’s impossible – “couldn’t put Humpty together again.” Even mended, he’ll never be the same. It’s the idea of an endless moving spiral, like the grooves on a record. The title seemed particularly appropriate with respect to the massive campaign to restore the centre of Paris in preparation for the Olympic Games, as well as to all the issues of destruction, but above all of preservation, surrounding the event.

“For me, cracks in the ground are a space to aim for, to occupy.”

You also decided to restore Le Défenseur du temps [The Defender of Time, Jacques Monestier’s giant automaton clock, installed in Paris’s Quartier de l’Horloge in 1979, which is being shown at Lafayette Anticipations].

Le Défenseur du temps was an obvious response to your invitation. I’ve always wanted to breathe new life into someone else’s work. I’m very interested in the fate of public artworks, especially those that end up in a state of anonymity. Le Défenseur du temps is all the more symbolic as a stopped clock. I remember seeing it work as a child and feeling a great sense of strangeness. It was an enigma whose nature or origin I couldn’t grasp. It was located in a side street near the Centre Pompidou, but in the eyes of a child it was much more interesting than the museum. I remember often passing through this interstitial, pedestrianized space, which lends itself to wandering. The clock is located between the Centre Pompidou and the Musée des Arts et Métiers, but has no place in either. It exists in a counterspace, as Foucault would say. If I hadn’t intervened, its days were probably numbered – it was filled with 300 kg of pigeon droppings and was in danger of collapsing. Questions of architectural and cultural conservation are only interesting to me when they’re linked to questions of the preservation of beings, of the self. I have an emotional relationship to architecture: for me, a building in ruins is like going without sleep or having a fever.

In HumptyDumpty, the human often has a complex relationship to history and the built environment, as can be seen in the other artists’ works you’ve chosen for the shows: Giorgio de Chirico’s anonymous figures digesting layers of architecture; Smithson’s drawings where signs of the city, language and myths implode in an internal crisis; Käthe Kollwitz’s figures that become monstrous by trying to protect childhood from the forces of time and the barbarity of war. What place does the human have in your own work?

The human appears very little in my own work. At one time I always kept a little Sony Handycam with me and filmed everything. For the video Lake Arches, which I made when I was very young, my initial idea was to shoot an idyllic scene with two friends swimming in the lake, starting with a close-up of the sky reflected in the water and then zooming out to show Bofill’s architecture – not a particularly good work to be honest. I started filming, one of them dived in a little too vertically and came out with a scratched, bloody nose. It aptly represents the idea of a confrontation between man and architecture, but also the way our bodies and environments are entangled. It reminds me of a work by Hajo Rose who, also when he was in his 20s, did a self-portrait with his face intertwined with the façade of the Bauhaus.

Heritage conservation developed over the 20th century with the idea of making objects permanent. Today there are 121 million items stored in French museums! But this obsession leads to a strange reality, since to preserve them the works must be cut off from the world in stable conditions, removed from the effects of time, seasons, day, night and light.

Yes, these are recent ideas. Moreover, it’s an obsession that goes against preservation of the planet, because keeping museums and their reserves at a constant temperature of 21° C has inevitable environmental consequences. The desire to preserve these works goes against preservation of the Earth and its living beings. It’s this jumble of issues that interests me: one is always preserved to the detriment of the other. But if there’s nobody left, who are these works for? The Palais de Tokyo’s cold draughts pushed me to show fragile pieces like Giorgio de Chirico’s The Archaeologists there, but I also had to find a way to install the painting without damaging it. The idea was to show it in a context different from normal museum standards so as to underline its fragility. But that meant altering it visually: a painting becomes a sculpture the moment it’s placed in a glass case. This idea of care and consideration is reflected in the subject of the painting itself: two figures each with one hand on the other’s shoulder, with a hydrometric control system at their feet like an artificial breathing device.

The fact that the preservation of certain things leads to the deterioration of others comes back in your work Love Locks, shown at the entrance to the Palais de Tokyo. They’re industrial-strength garbage bags filled with “love locks,” the padlocks that tourists attach to Paris’s bridges, whose combined weight threatens the bridges’ stability. What gave you the idea?

I thought about them one day while walking through the city. They aren’t put there by Parisians but by couples from the US, Asia and elsewhere. They symbolize the permanence of their love, sealed in the padlocks after the key is thrown into the Seine… It’s a gesture of great irony, isn’t it? The padlock as an expression of love, when it also represents imprisonment. I imagined this work as a readymade. These padlocks don’t pose an ethical problem so much as a physical one: at the Pont des Arts, their weight caused part of the railings to collapse, so in 2018 they were all removed and the wire railings replaced with large panes of Plexiglas. It’s like Oscar Wilde’s tomb at Père-Lachaise, which is now under glass to protect it from all the lipstick kisses left by his fans. But the glass changes it. These examples highlight the paradox: preservation destroys. The irony inherent in attempts at conservation is that they destroy our access to a work in the here and now while ensuring its continued existence for future generations.

In your piece Formation, Düsseldorf’s rather generic architecture is put into perspective through the presence of parakeets, which are considered an invasive species in the city. The question of an original, standard, normal state of place arises – a state that has been altered by the birds’ presence.

A few years ago, in New York, I became interested in birds. During the migration period they stop over in Central Park, which makes it a great place to watch them. I spent time observing them through binoculars as well as trying to understand the community of avid ornithologists eager to expand the collection of birds they’ve seen but haven’t possessed: for them, the mere fact of seeing a bird is enough to create a collection. That seems right to me: memory is a collection. But their way of observing birds is academic, directly linked to identification – male, female, juvenile, endemic, migratory, etc. Bird watchers are also interested in environmental issues and often perceive species introduced by man as harmful. This hierarchy of wildlife, as established by humans, caught my attention. The ring- necked parakeet, which is native to southern India, was introduced to Europe as a pet and gradually spread to many parks, such as London’s Kew Gardens and Paris’s Jardin du Luxembourg. The parakeet has a double identity: it’s considered harmful by some because it disturbs existing ecosystems, but is admired by others because it symbolizes a kind of freedom regained, since these are the descendents of caged birds. In my film, we see parakeets flying over the Königsallee in Düsseldorf. They’re non-migratory tropical birds that live in the interstitial spaces that are the streets and parks of Düsseldorf, finding legitimacy neither in freedom nor in captivity.

“I have an emotional relationship to architecture.”

The interstitial space that is the Königsallee is also their bio-corridor. I admire their resilience. But in wildlife documentaries, parakeets are only ever shown in their original habitat, the wild landscapes of southern India. In Düsseldorf they found virgin ground to occupy, a new interstice. So I filmed them using the codes of animal documentaries: long shots, slow motion and above all from a low angle, because seen from the ground the birds appear against the light, which means we can’t admire their plum- age. When it rains, like in my film, the parakeets fly quite high, passing in front of the Königsallee buildings, some of which date from before the war while others are more re- cent, like Daniel Libeskind’s Kö-Bögen, which reminds me of the Rheinmetall headquarters, which are also located in Düsseldorf. Rheinmetall is one of the largest arms producers in Germany and has been operating in the region since the late-19th century. Historically, the Ruhr was the centre of the arms industry – this is why Düsseldorf was heavily bombed during the war. These Indian parakeets flying over the Königsallee at twilight immediately made me think of a military formation. In an irony of history, this tropical bird has invaded the city and gradually gained the upper hand over German birds in a kind of reverse colonialism.