7

7

Leonardo da Vinci: new secrets about history’s most expensive artwork revealed in a film

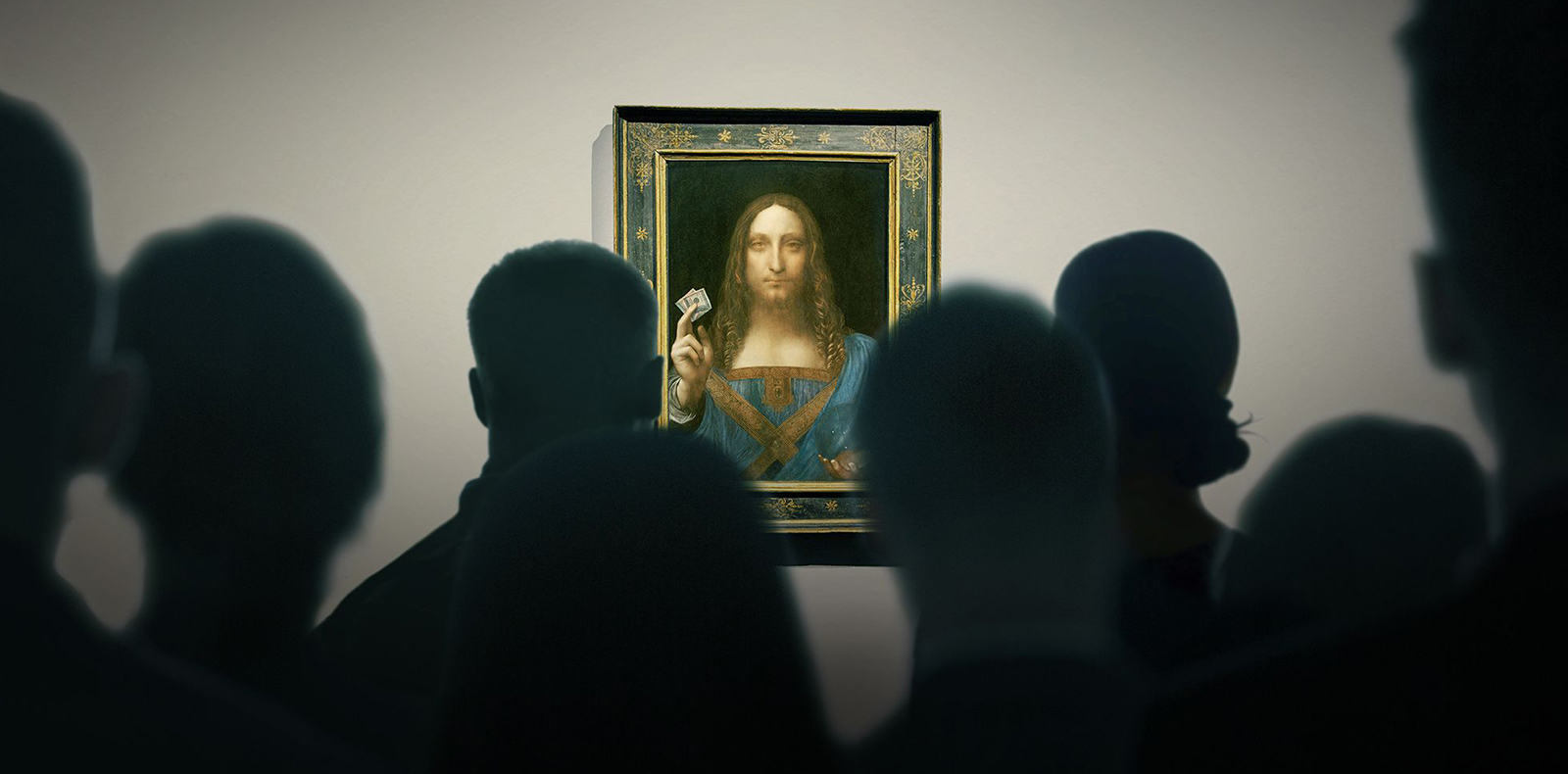

In 2017, the Salvator Mundi became the most expensive artwork in history at Christie’s auction sale. Since then, the canvas attributed to Leonardo da Vinci is at the core of many controversies, whether they are about its purchase by Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman or about the painting’s real connection to the Italian master. After the French journalist Antoine Vitkine, Danish director Andreas Koefoed recounts the epic of this fascinating piece of art in his documentary The Lost Leonardo, released on January 26th, 2022.

By Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 7 February 2022. Updated on 20 June 2024.

Five years after its sales record for an amount of $450 million, the Salvator Mundi has not yet finished to unleash passions. Attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, the painting has become the most expensive one in history at Christie’s auction sale. Now, it is the topic of a new documentary by Andreas Koefoed intitled The Lost Leonardo and was released on Wednesday, 26th January – only a few months after the screening of a film made by journalist Antoine Vitkine (available on the French TV channel France 5), which was telling the outlandish story of the artwork after a two year-long investigation. Indeed, the Salvator Mundi case has every element of a decent thriller: from its discovery in a sales catalogue in New Orleans and its auction sale at Christie’s for an amount about 400 000 times higher than its original price, to its exhibition at the National Gallery and its noticeable absence during a retrospective dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci at the Louvre in 2019, the artwork’s story is peppered with plot twists. Even more unbelievable given that the owner’s identity, Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman, gives the artwork a political dimension, while some experts question its filiation to the Renaissance master, and thus its market value.

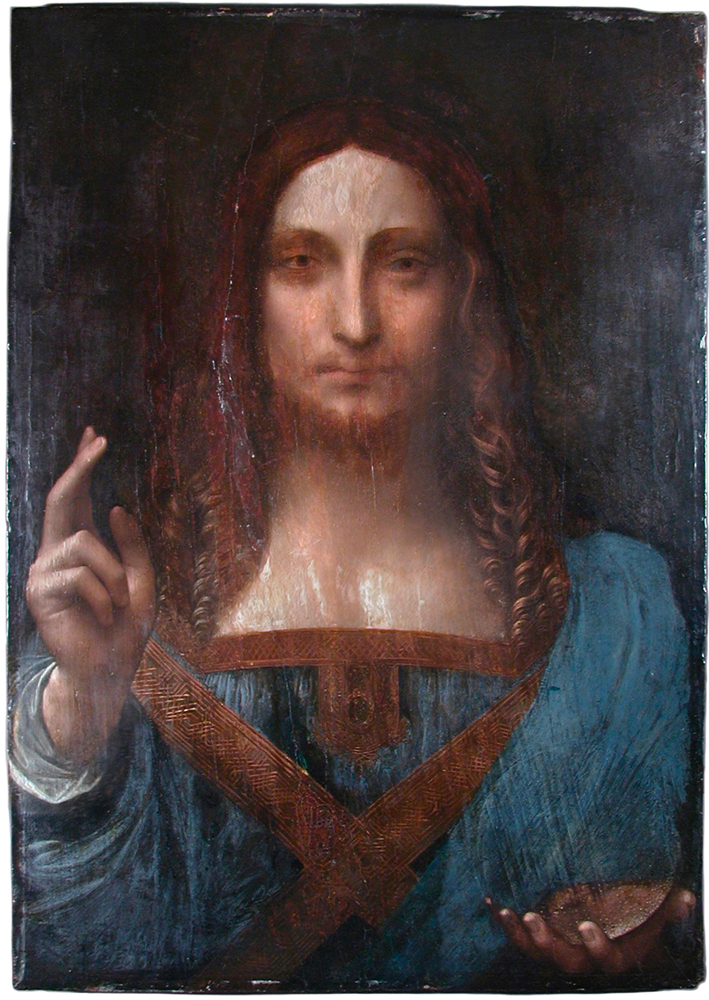

“Have you seen this canvas in the next auction sales in New Orleans?” It all started from there… a call made by art hunter Alexander Parish to American art dealer Robert Simon. In a sales catalogue, Alexander Parish noticed a very damaged canvas depicting Christ the Redeemer with his right hand up and his fingers clasped as a sign of benediction, along with the mention “after Leonardo da Vinci”. Convinced they got hold on an unknown work probably made by the master himself – only fourteen paintings by Leonardo da Vinci are known today – the two men bought it for the ridiculous amount of $1,175. From that point, the canvas’ huge story begins, as emphasized in the opening scene of Andreas Koefoed’s movie: mimicking the credits of Games of Thrones, an aminated map shows the painting’s route around the world for the last sixteen years. The artwork goes from art restorer and Renaissance painting around the world for the last sixteen years. The artwork goes from art restorer and Renaissance painting specialist Dianne Modestini’s hands, to the National Gallery’s picture rails for the 2011 retrospective dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci in London – the event officialized the link between the work and its author – and then into Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev’s hands, who bought it for $127.5 million before letting it go at Christie’s 2017 auction sale in New York. The artwork would make history between those walls, even before his owner’s name would be revealed.

If Andreas Koefoed’s film does not disclose any shocking element in comparison with the previous documentary, it surely deepens our understanding about some details in the case. We can find the main characters already existing in Antoine Vitkine’s documentary, such as the expert Martin Kemp and National Gallery ex-curator Luke Syson, who both agreed to host the Salvator Mundi within the London institution. Businessman Yves Bouvier himself is back too – he is the one who sold the canvas (for more than twice its original price) to the Russian oligarch. Going even farther than in Antoine Vitkine’s film, some protagonists confirm their belief in the “feminine Mona Lisa”’s connection to Leonardo da Vinci when facing the camera. The voice of the painting’s restorer Dianne Modestini is by far the most contrasting one from the first film. Among all the characters of the case, she is the one who kept the canvas with her for the longest time and who analyzed every single detail about it. No doubt here, the Italian master did it. For that matter, the numerous paint touch-ups she added were so well done that experts worldwide were convinced too. Known for his cynical and provocative stances, art critic Jerry Saltz remains cautious. He criticizes the amateurism of these valuations and declares that “the worst thing in this case is that the painting is not even a good one!” Following that sceptic position when seeing the restored version, expert Frank Zöllner is convinced that the canvas was made in Leonardo da Vinci’s atelier, but not solely by the master’s hand: “The artwork is more Leonardesque than Leonardo himself could have done!”

The Lost Leonardo brings up some opportune elements in the canvas’ story. Thanks to the film, we learn that the night before the sale at Christie’s, the future owner Mohammed bin Salman had already transferred $100 million to the house to show his interest in the painting, leading the organizers to question the mysterious collector’s identity, who clearly was not used to auction policies. It also exposes a testimony from a journalist present at the Louvre exhibition’s press release in 2019. While uncertainty surrounds the presence of the Salvator Mundi among the selected artworks, the journalist recalls walking in a hurry through the exhibition and witnessing an empty space limited by four hooks on one of the walls – a hint of the last-minute absence of the painting. Shortly after the opening, the Salvator Mundi was finally part of exhibition, but as a mere copy, thus emphasizing the doubts about the original. The film also reminds us that the Louvre edited a booklet that confirmed the canvas’ authentication – it was available to the public before being suddenly removed from the museum shop. If this removal could have been interpretated as proof for the canvas’ lack of authenticity, the documentary reveals that it may stem from another motive. Eager to strengthen the international aura of his canvas, his owner Mohammed bin Salman had denied the Louvre the loan of the work because the French institution refused to accept his terms: the Salvator Mundi should have stood next to the Mona Lisa – history’s most famous work of art in the world’s most visited museum.

Despite many enquiries and a long process of research, clear gaps remain in the Salvator Mundi case. Neither the National Gallery, nor the Louvre, are willing to speak out or display the result of their valuation to the public eye. The mystery surrounds the exact location of the work too. Journalist Kenny Schachter was the last one to disclose its presence on Mohammed bin Salman’s yatch back in 2019, but no one knows if it is still there today – some even dream of a coming resurgence of the work in museum dedicated to it in Saudi Arabia. A tad sensationalist, the one-hour-and-forty-minute-long documentary allows us to dive into the details of this fascinating case, fed by the intervention of 25 speakers. As the subtitle underlines it, it is an impressive case in its scope that unveils the contemporary intricate links between art, money, and above all, power.

The Lost Leonardo by Andreas Koefoed, screening since January 26th, 2022.