15

15

Keunmin Lee, painter of the body and soul torments

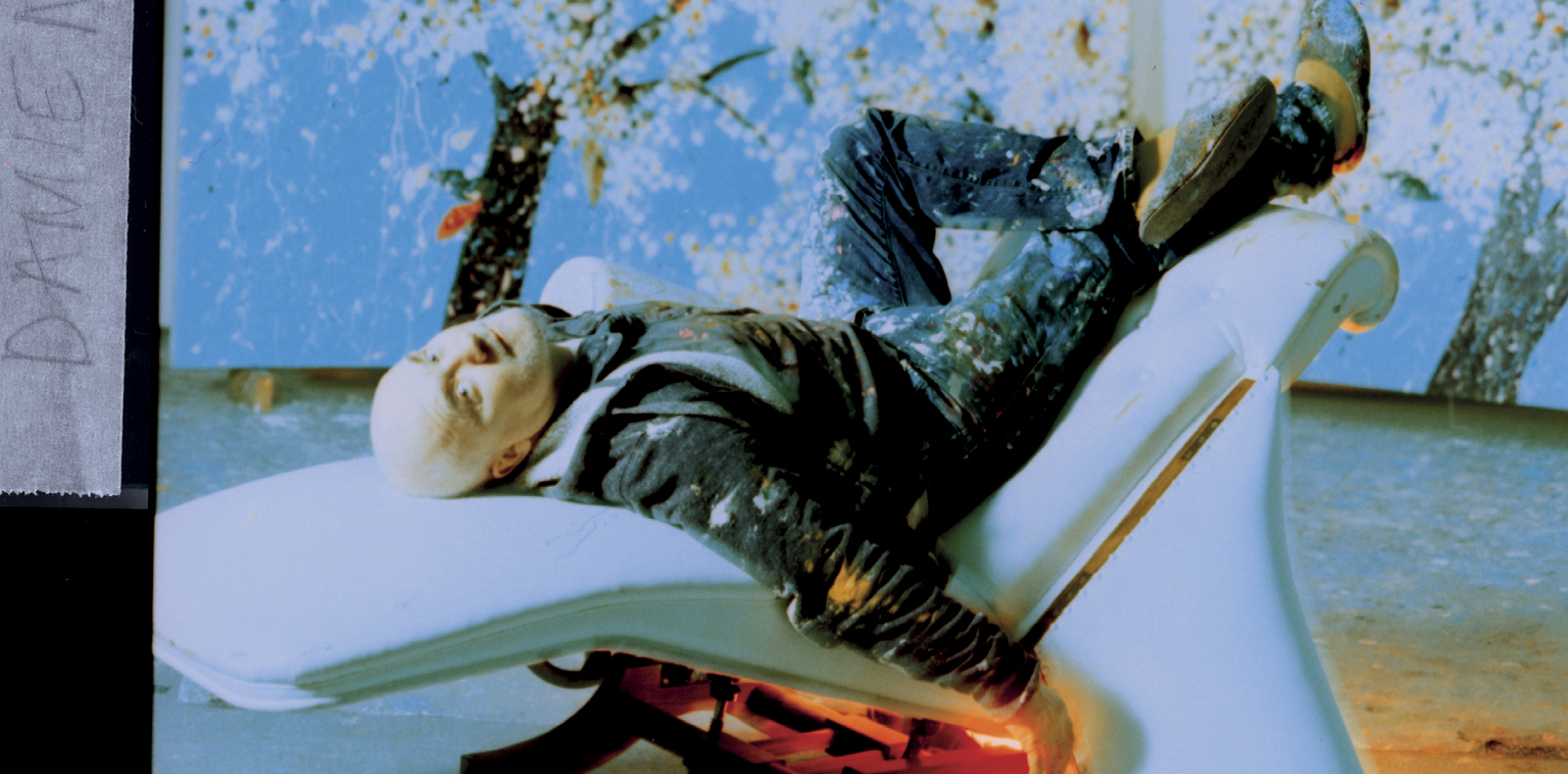

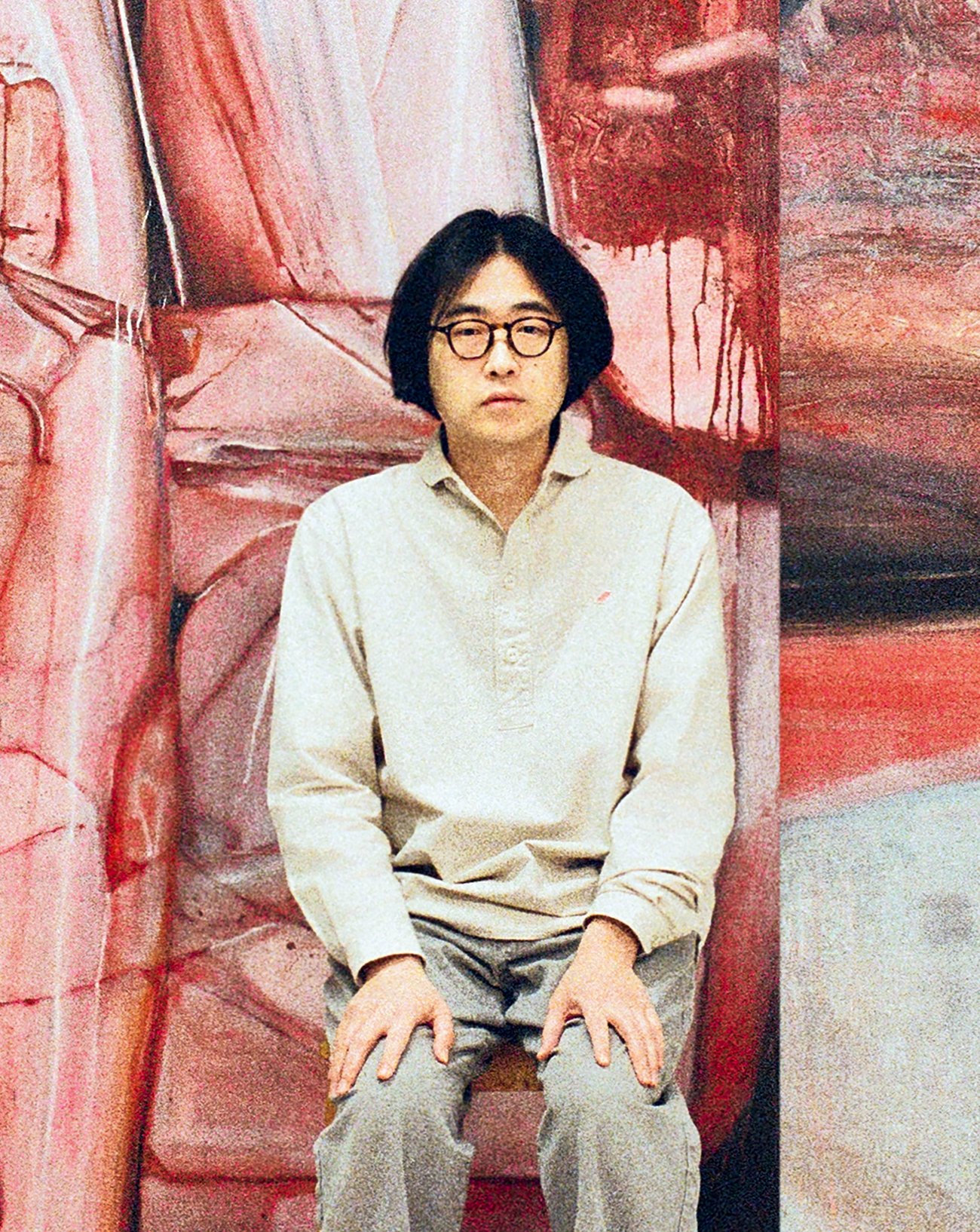

Inspired by his delusional episodes, Keunmin Lee’s impressive paintings thrust us into a crimson, carnal world made up of blood and viscera. Little-known in France, the 43-year-old Korean artist recently staged his first solo show in Paris at the Galerie Derouillon. Numéro art went to see him at his Seoul studio.

Photos by Narang Choi ,

Text by Marion Coindeau .

Published on 15 May 2025. Updated on 29 July 2025.

Assistant photographer: Eojin Park. Image editing: Junho Choi. Production: Yoonjin Choi.

Keunmin Lee: the painter of sensations

Keunmin Lee’s immersive paintings capture sensations experienced during delusional episodes, plunging us into the rich crimson hues of a body that knows neither boundaries nor externality. By sharing his personal experience of mental illness, he exposes the relationship between the body, social structures, and their systems of control.

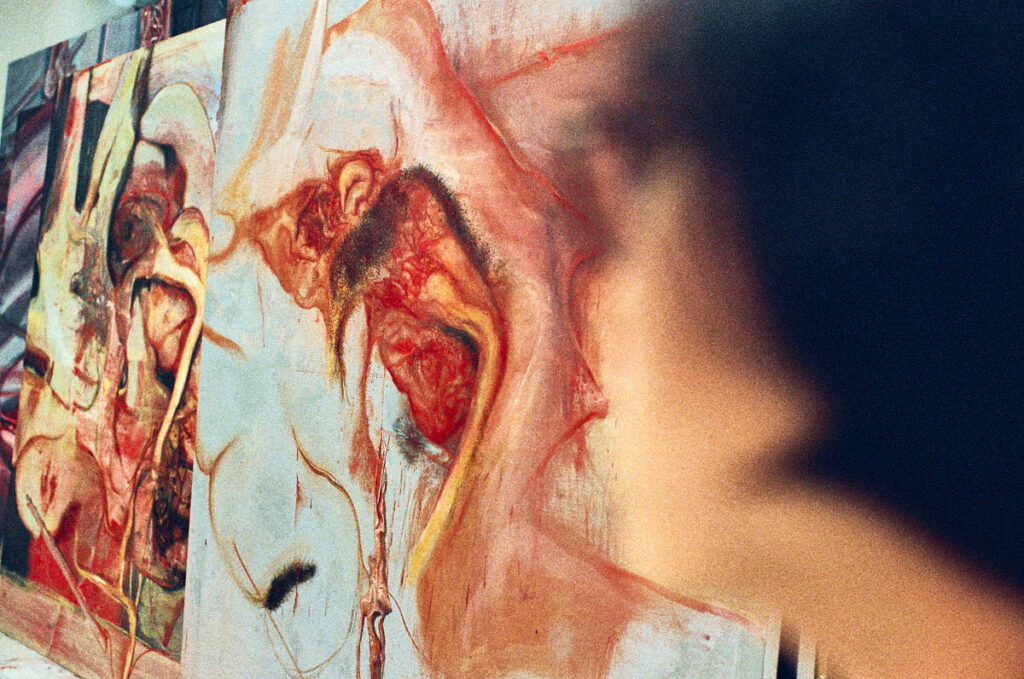

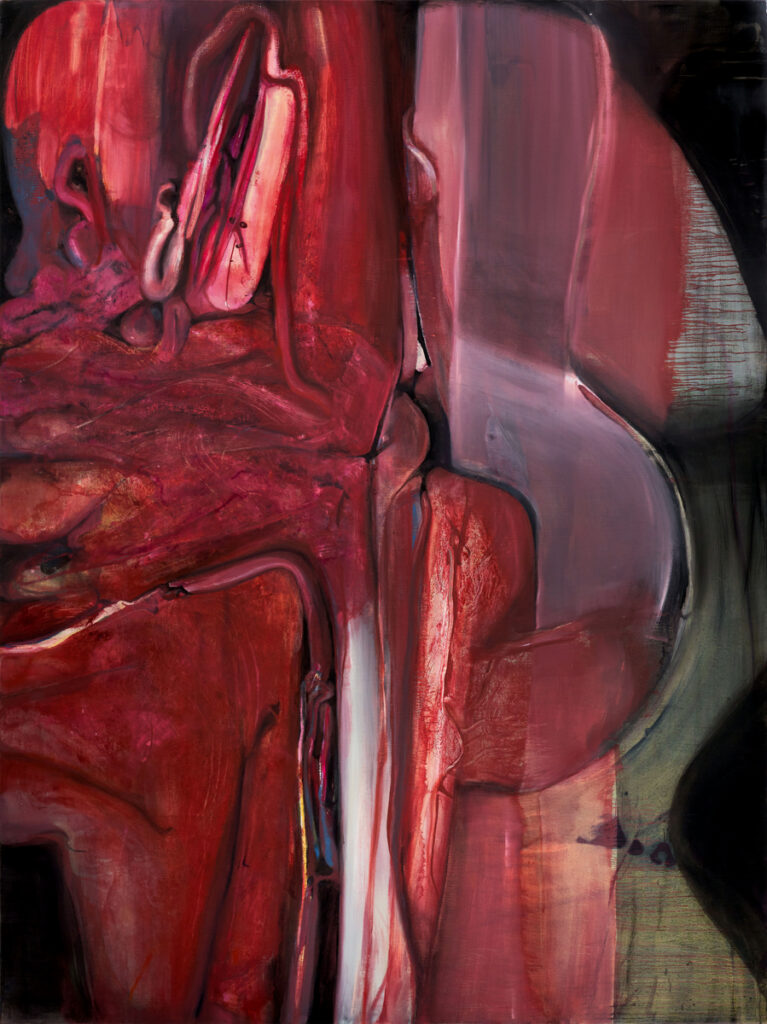

Francis Bacon saw painting as a way to “return fact onto the nervous system,” the same emotive nervous system we find at the heart of Lee’s work. His paintings depict what appear to be flesh, tendons, guts, and arteries rendered in variations of red, cold whites, dark browns, and grey-greens (Body Construction I, 2024).

Materializing social violence on canvas

If his work seems to engage our sense of touch before sight, it’s because it evokes the memory of sensations rather than precise images. For Lee, it’s a way of communicating the suffering body and the experience of violence without depicting it explicitly. It’s also about capturing those moments when we go through, or are seized by, violence and the emotions it brings – in this instance, the violence of illness and clinical rationalization.

Lee’s bodies are eminently political. “I’m interested in the violence of definition imposed by society. This is a result of my resistance to the duality of definition, which historically has labelled concepts such as primitivism, orientalism, foreignness, disability, and illness as by-products of civilization’s advancement.”

Art as a response to excluding and deathly norms

Inspired by Edward W. Saïd’s writings on orientalism, Lee’s approach is rooted in ideas about postcolonialism and Foucault’s exploration of insanity as a construct of exclusion and vested interests. At a time when many political reforms are increasingly exclusionary, it seems crucial to give greater voice to those on the margins.

Two decades ago, Lee was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, a term that spans a broad spectrum ranging from instability in relationships to extreme sensitivity to the environment. The cold rationality of this diagnosis appears like a cruel condemnation that reduces identity to illness.

Entering the torments of the flesh

Born in South Korea in 1982, Lee labors under the social expectation of a performative and productive masculinity whose accomplishment is hampered by his condition. Lee views vulnerability as a collective reality, bringing us face to face with the physical and emotional torments of the flesh in such a way that, when we contemplate his canvases, our bodies seem to enter another body (Connected Skin series, 2024).

Perhaps this is what a body cut off from all social context would look like, a kind of fragmentation, which is also found in the titles he gives his series and formats: Body Construction, Connected Skin, Psychiatrist’s Head, Organic Plate. Organic systems become a metaphor for social systems, which, in order to function, classify and digest individuals to the detriment of individuality and difference.

Rather than referring to an inherited visual culture, Lee triggers strong physical sensations through his paintings’ materiality. Blood is an essential component, a “bridge between a fantasized and a real space.” Lee accidentally injured himself during delusional episodes; the Connected Skin series features networks of blood vessels and red drippings, like so many threads linking viewer and artist.

“Incorporating my hallucinations into my artistic world (…) gave them subjectivity and deeper meaning.” – Keunmin Lee

Some of the small and medium-sized canvases include glued-on plastic film in apparent coagulation (Organic Plate, 2024). Then comes the delicacy of erased layers, like a palimpsest (Connected Skin I & III, 2023–24), whose softer greens and blues simulate the analgesic effect of time on these wounds – the healing of a metaphorical body through oil paints.

Painting as a act of resistance

Keunmin Lee reappropriates his illness through his artistic practice, an act of resistance that distinguishes itself from art brut in its constant self-reflection. Painting helps free him from the oppression of his diagnosis and symptoms. “For me, incorporating my hallucinations into my artistic world elevated them beyond mere symptoms of an illness. It gave them subjectivity and deeper meaning.” Only his drawings have a more personal vocation: rarely shown to the public, they form an extremely meticulous “daily pathology diary.”

In contrast to the lengthy process of oils, Lee seeks the immediacy of surrealist automatic drawing in order to keep idea and gesture in the same temporality. Lee’s art is an introspective and emancipatory process; by keeping this “pathological diary” he gives substance to experiences that escape societal norms and appeal to our deepest interiority.

Keunmin Lee is represented by the Galerie Derouillon in Paris.