26

26

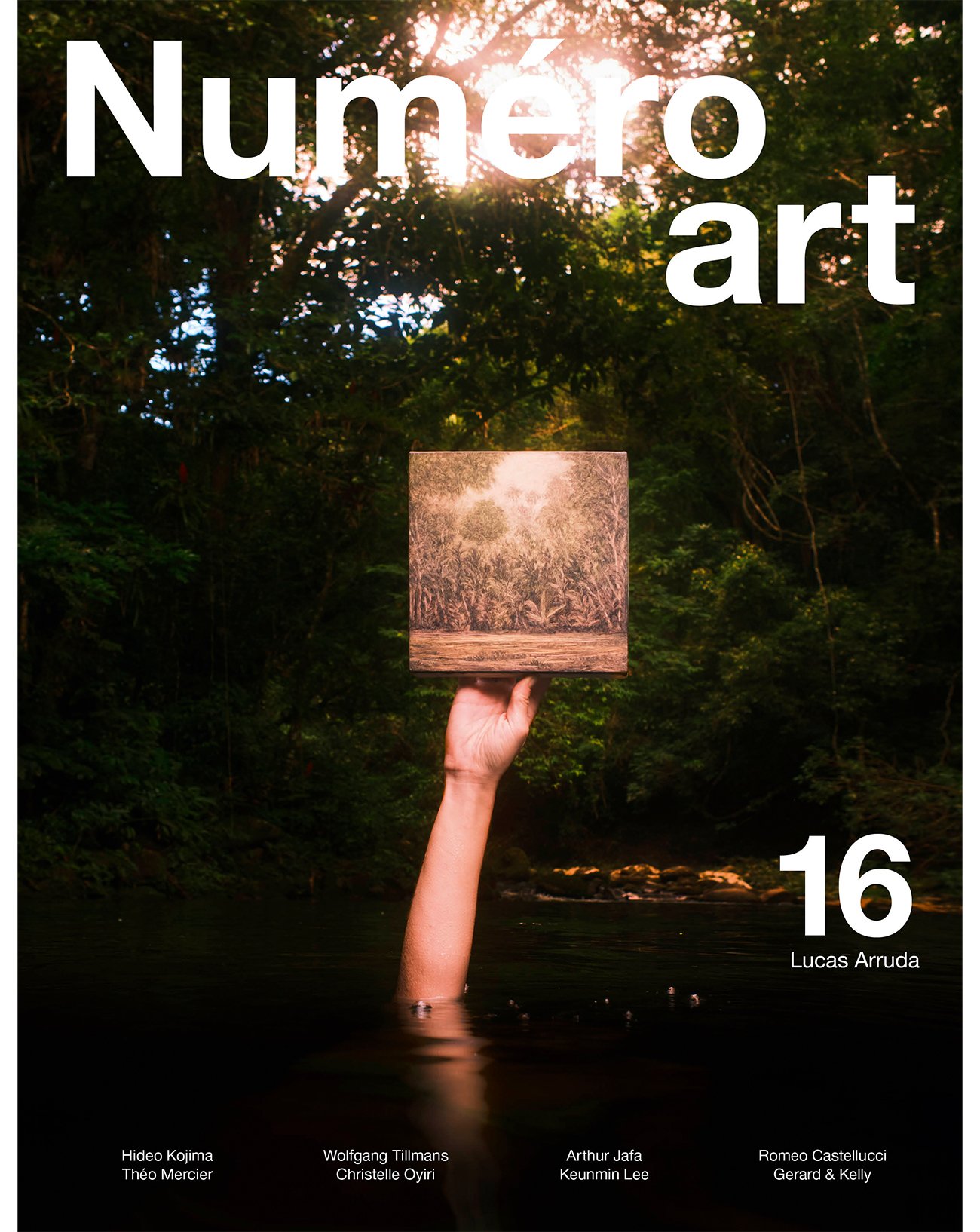

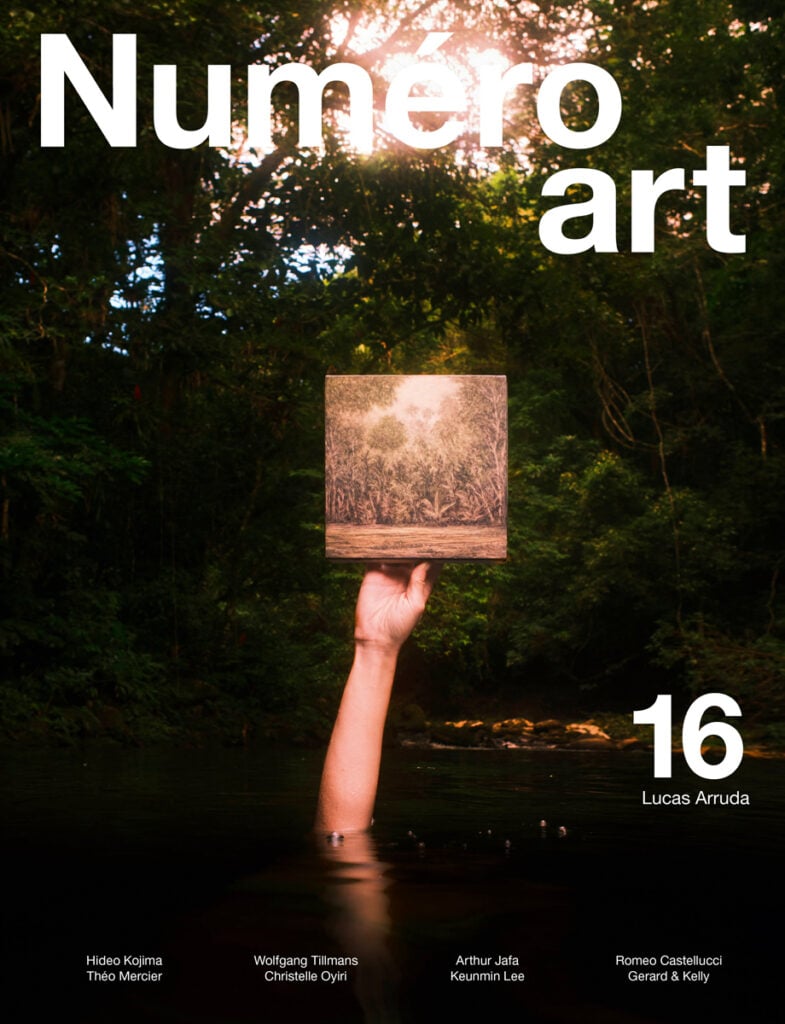

Interview with Lucas Arruda in Brazil: the painter on show at the Musée d’Orsay

Known for his small-formats of ethereal horizons and dense forests, Brazilian artist Lucas Arruda had never held a major exhibition in France before. It is now happening this spring, with simultaneous shows at Carré d’art in Nîmes and at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Numéro art traveled to Brazil to meet him and explore the landscapes that haunt both his canvases and his memory.

Photos by Vidar Logi ,

Interview by Fernanda Brenner .

Published on 26 May 2025. Updated on 7 July 2025.

Lucas Arruda, the painter celebrated at the Musée d’Orsay

“The curators and I agreed that Courbet’s La Mer orageuse should be positioned closer to my works,” Lucas Arruda told me on the telephone. There was something characteristically precise in this request – not the entitled demand of an artist full of his own importance, but the search for a necessary dialogue across centuries.

“It’s not about prestige,” he continued, as though answering my unasked question. “When I stood before that canvas, I saw Courbet wrestling with exactly what consumes me: that threshold where sky becomes water, not as separate kingdoms, but as transformations of the same substance.” The line went quiet for a moment. “That’s the space I’m trying to inhabit.”

This conversation took place midway through preparations for Lucas’s exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, a major event in the museum’s history since this is the very first time it has programmed an artist from the southern hemisphere. Showcasing the full breadth of his oeuvre, from ethereal horizons to dense forest interiors, Qu’importe le paysage, as the Orsay exhibition is titled, speaks to the universal language of Lucas Arruda’s work and to its resonance beyond geographical boundaries.

I couldn’t help but wonder why it had taken so long – the same colonial gaze that for centuries viewed Brazil’s Atlantic Forest as an infinite resource to be harvested had similarly determined who entered the canonical palace of European art history. But Lucas, as ever focused on the work itself, pivoted back to Courbet before I could wade into those political waters.

Endlessly painting the Brazilian horizon

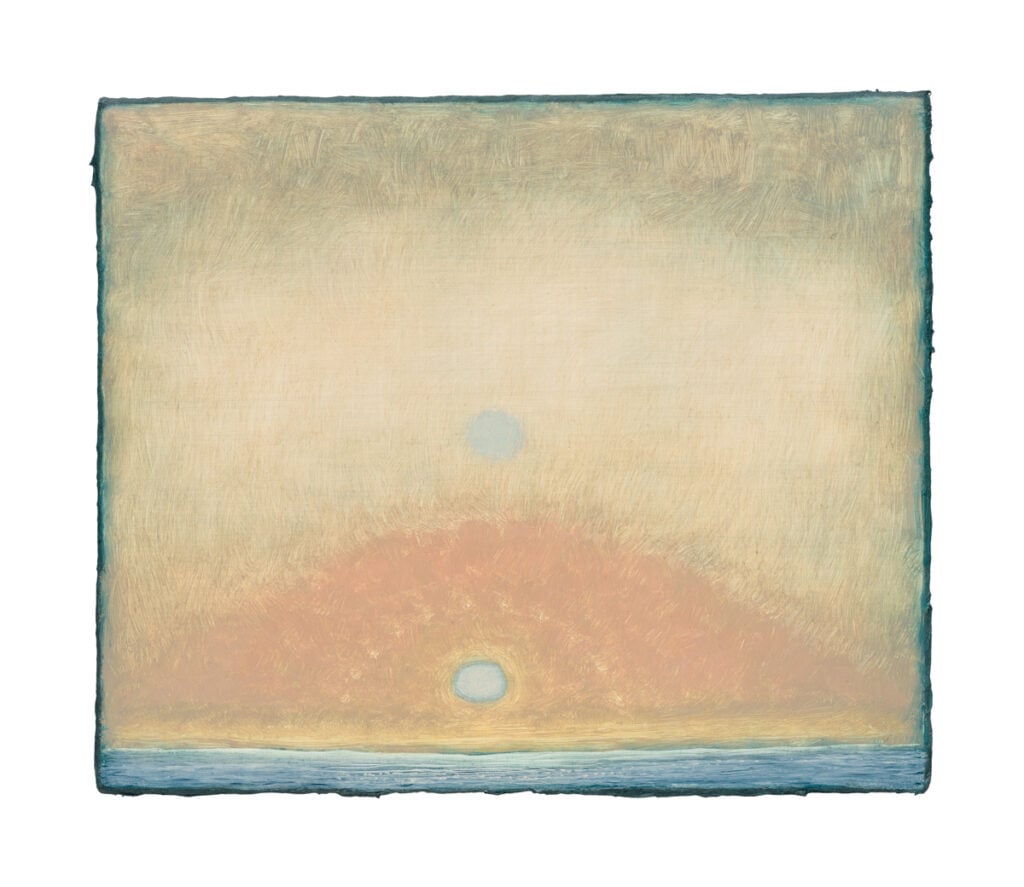

In 2010, when I first became acquainted with Arruda’s work, the Brazilian art scene buzzed with explicitly political pieces addressing social hierarchies and historical wounds. Against this backdrop, Lucas’s small, luminous horizons seemed almost defiantly introspective. In his São Paulo studio, a converted industrial space where everything seems calibrated with laboratory precision, works emerge under the single designation Untitled (Deserto-Modelo).

This ongoing series, which comprises dozens of pieces, encompasses not only those ethereal horizons and luminous,

monochromatic fields, but also his haunting 35 mm slide projections, his occasional film pieces, and the dense Atlantic Forest paintings, which have increasingly occupied his attention. All exist within this same conceptual framework – different materialities exploring a consistent philosophical terrain.

Lucas Arruda’s meditation on landscape

The umbrella title, borrowed from the Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto, suggests landscapes that exist simultaneously as physical reality and conceptual construct. “Engineers, armed with blessed projects, managed to build an entire deserto modelo,” Lucas once quoted, his hands moving in that deliberate way they do when he’s trying to articulate something essential. This desert, this ground zero of perception, acts as both subject and methodology in Arruda’s practice.

As Spanish art critic Victor del Río argues in Políticas del paisaje, the desert functions as the foundational figure of landscape itself – the emptied field where representation is simultaneously possible and questioned. It deactivates the symbolic importance of things, stripping away conventional signifiers to reveal perception in its most essential state. Through minimal gestures – the slightest calibration of tone, the whispered suggestion of a horizon – Arruda does not so much depict landscapes as evoke the very act of perceiving them.

A central subject: light

Though well versed in art-historical lineages – tracing, for example, precise connections between Agnes Martin’s meditative grids, Armando Reverón’s spectral luminosities, and John Constable’s cloud studies – Arruda resists designation as the heir to any particular tradition.

Once, after an hour of nuanced analysis of Turner’s technique, he paused, looking almost embarrassed by his own erudition. “But these are just tools, just references,” he said. “Light is my real subject. Not painters or movements, just light.”

This wasn’t evasion, but a distillation of his practice to its very essence. Years later, this remains the quote I always return to when writing about his work, not from laziness on my part but because it captures something fundamentally true about his approach, which is as quiet, precise, and elusive as the phenomena he paints.

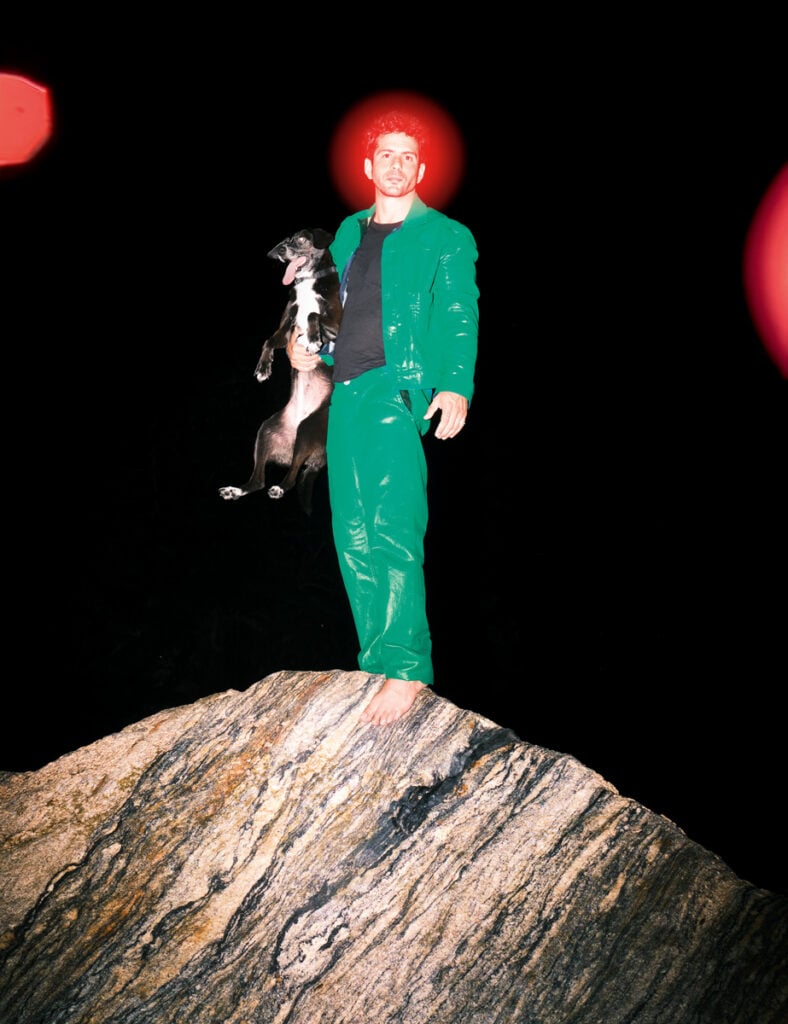

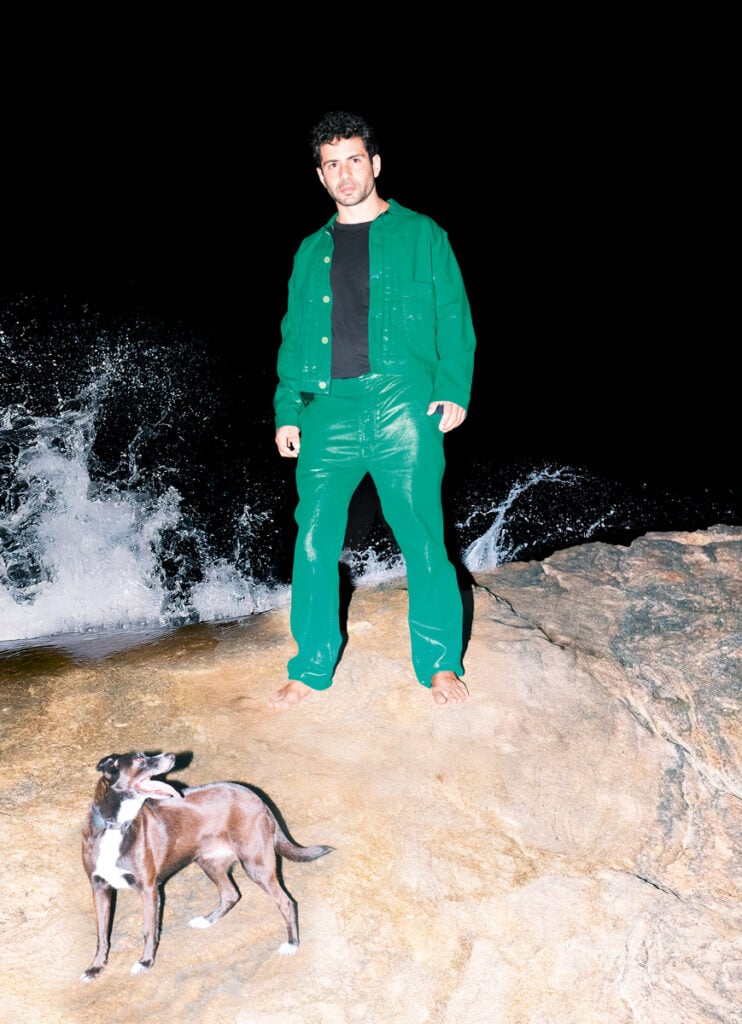

The artist’s studio in São Paulo

There’s a quality to Lucas’s studio I’ve never encountered elsewhere – a monastic hush that somehow persists even when São Paulo’s cacophony forces its way through the

windows. He works under artificial light that he adjusts with obsessive attention, as though light itself were a pigment to be mixed. His dog occasionally pads across the concrete floor, pausing to observe her master with an attention that rivals his.

Standing in this space, watching his canvases shimmer with what I’ve come to think of as the “Arruda flicker” – that visual instability where solid forms become translucent as the eye shifts – I often find myself recalling the opening lines of Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves: “The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it.” What Woolf captures is exactly the perceptual threshold Arruda pursues, that moment when distinctions haven’t yet clarified, when sea and sky exist as variations of the same substance.

Months of work and layers of paint

The most striking aspect of Lucas’s process is its dramatic oscillation between methodical patience and urgent intensity. His monochromatic works are built up through months of meticulous layering. He begins with pre-dyed canvases from São Paulo markets, matching them precisely to pigments.

White paint is banished – ”It yellows, it decays,” he once explained, with a technician’s attention to chemistry. Instead, he builds luminosity through complementary colors, creating what he calls “phantom light” that materializes gradually before the eyes of the patient observer.

© Lucas Arruda. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Mendes Wood DM.

© Lucas Arruda. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Mendes Wood DM.

His cold encaustic technique, which involves incorporating beeswax into paint, produces surfaces that seem to breathe with the room. “The paintings are like skin,” he remarked during a studio visit last year, running his fingers along a dried surface. “They record every interaction, every trauma. Nothing is permanent.” I thought then how this might apply to the Brazilian landscape itself, scarred as it is with the traces of centuries of extraction.

In contrast, his landscape works demand marathon sessions where he works wet-on-wet, allowing paint to dictate its own rhythms. During these moments, he becomes almost feral in his concentration – pacing, muttering, refusing interruption. This duality between slow accumulation and rapid emergence creates a visual tension that makes his works feel simultaneously ancient and newly born.

The forest: a portail to an imaginary world

The Atlantic Forest has long featured in Arruda’s canvases, though he doesn’t paint from direct observation. Instead, these dense, vertical compositions emerge from memory, the forest being a place he has visited since childhood, one whose atmospheres he carries inside him. “Memory is more accurate than looking,” he once told me, an approach that paradoxically connects him to the Impressionists, whose work surrounds his at the Musée d’Orsay. While Monet and his contemporaries painted en plein air to capture immediate sensations of light, Arruda retreats inward, finding that same immediacy in remembered experience.

“The forest is another kind of passage,” he explained. “Not horizontal like the horizon, but vertical and entangled. You don’t see through it; you see into it.” The conversation then turned to the forest’s destruction – today, its surface area has been reduced to less than seven percent of its original coverage as a result of centuries of colonial and industrial exploitation.

Though Lucas rarely makes explicit political statements, his refusal to fix locations or define territories in his work offers

its own quiet resistance to the commodification of land. As Victor del Río might suggest, by withholding the signifiers that would place these landscapes in identifiable territories, Arruda subtly undermines the very codes that have historically made the depiction and description of landscape a tool of power and possession.

A week after our phone call about Courbet, he sent me a text from the Atlantic coast, where he periodically retreats from the concrete intensity of São Paulo. “The horizon is always different here,” he wrote. “It moves even when I don’t.” In this simple observation lies the essence of Arruda’s practice – the recognition that what appears most stable is actually in constant flux. His paintings register this paradox, fixing on canvas the precise moment when light becomes visible, when form emerges from formlessness, when the eye first distinguishes sea from sky. They capture not the landscape itself, but that fleeting threshold where perception begins.

© Lucas Arruda. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Mendes Wood DM.

© Lucas Arruda. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Mendes Wood DM.

1. Translation from the English by Cécile Wajsbrot (Christian Bourgois éditeur, 2008).

“Lucas Arruda. Qu’importe le paysage”, exhibition until July 20th, 2025, at musée d’Orsay, Paris 7th. “Lucas Arruda. Deserto-Modelo”, exhibition until October 5th, 2025, at Carré d’art, Nîmes.