23

23

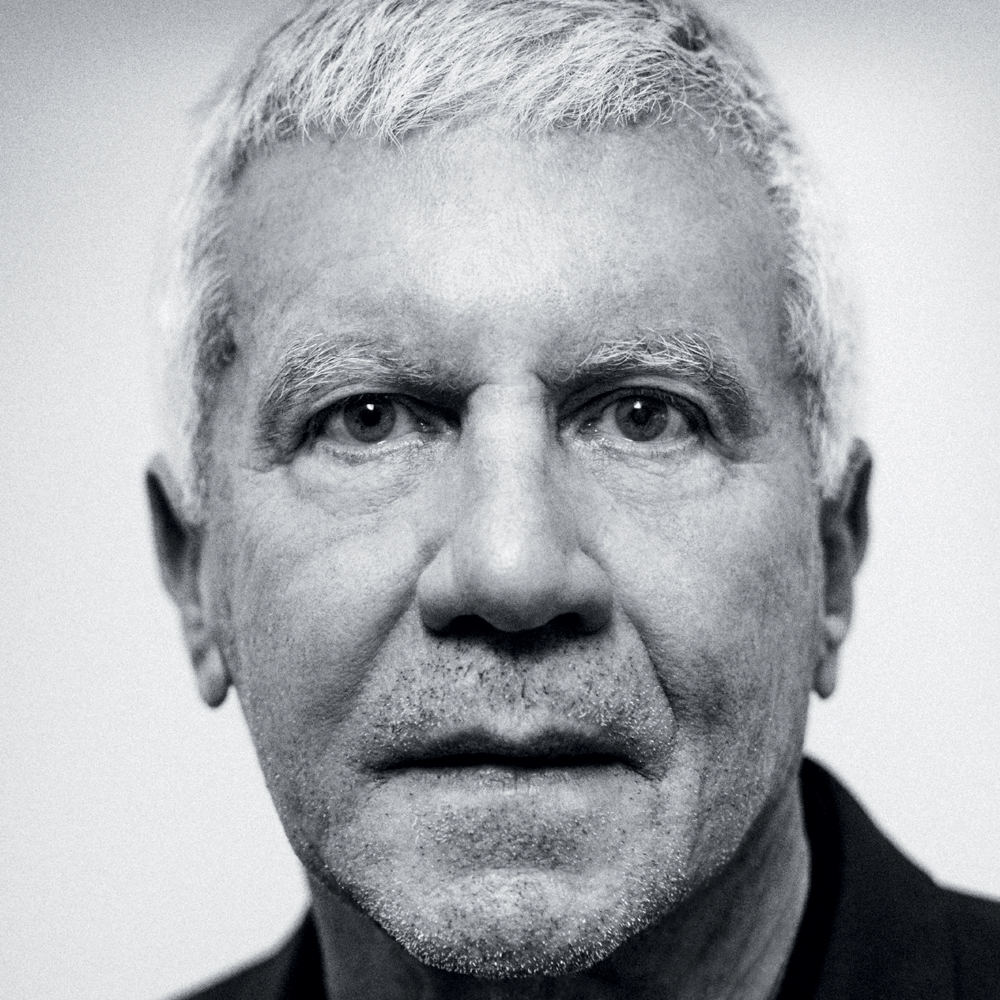

State of the Art: Conversation between Larry Gagosian and Roberta Smith

Roberta Smith, who retired from The New York Times in 2024 after a decades-long tenure, including 13 years as co-chief art critic, is one of the most feared and respected voices in American art criticism – closely rivaled by her longtime husband, Jerry Saltz. Larry Gagosian is the world’s most powerful art dealer, with a global network of galleries that has redefined the business of contemporary art. For Numéro New York, the two sit down for their first-ever extended conversation, a landmark, decades-in-the-making exchange between two titans of the art world.

Interview by Roberta Smith ,

portraits by Inez & Vinoodh .

The first-ever extended conversation between Roberta Smith and Larry Gagosian

Larry Gagosian and I have both been part of the New York art world for around four decades. I’ve seen many of his gallery’s exhibitions—reviewed some of them, too—and it’s likely he’s read some of my writing. But until this interview, we had seldom exchanged more than “Hello, nice to see you,” and the occasional air kiss. By now, Gagosian’s origin story is the stuff of legend: raised in a middle-class household near Los Angeles with no exposure to art, he earned a degree in English literature from UCLA. Casting about for something to do, he once saw someone selling posters from the trunk of a car and thought, “I can do that.”

The only way was up. An autodidact, he discovered his passion for art—and art dealing —through relentless looking, listening, and a few key mentors, most notably the legendary art dealer Leo Castelli. Cold-calling collectors and dealers with uncommon tenacity, he worked his way into the upper echelons of the art world, ultimately redefining what a gallery could be.

He pioneered a model that balanced landmark historical exhibitions with shows by contemporary—and occasionally emerging—artists. Describing himself as ambitious, competitive, and tenacious, he built a global network of galleries unlike anything the art world had seen, a network so expansive that, as he once put it, “the sun never sets” on it. Here we have our first real conversation, discussing the trajectory of his career, his epiphanies, his artists, and some of the nuts and bolts of running his empire.

Interview with Larry Gagosian

Roberta Smith : Let’s start where most interviews end: how do you see your legacy? You’ve been described as having reshaped the art world, taking art dealing to the level of a “blood sport.” How do you see it?

Larry Gagosian : I take a lot of pride in the fact that we—for better or worse—created a new model of what a gallery could be. And other galleries have followed that, opening galleries in different locations. I guess it’s flattering in a certain way. It was just an instinct that I had. I thought it would be an interesting way to build my business and offer things to artists that a single gallery couldn’t. It wasn’t some grand plan.

I was just curious to see what I could do. It just kept going. I thought it was fun opening galleries in different parts of the world. Also, we could reach collectors who don’t necessarily want to live in New York—or London, for that matter. What’s also been very successful commercially is that somebody will find a work in Athens and we sell it to somebody in Hong Kong. There’s a lot of art moving around within our structure that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. It’s a big headache in many respects, but I just enjoy the complexity of it.

What’s the chain of command? Are you okaying everything?

No, no. But I think, people kind of know what we want, what I want. Also, I can’t micromanage eighteen galleries. It’s impossible.

So would the situation arise where one of your non-New York galleries shows an artist or a body of work you’re not familiar with?

Not really. I call up almost all of my directors, almost every day.

Sounds scary.

Well, we get along pretty well. I hope it’s not too scary. I like to keep in touch, to use the telephone and I appreciate the immediacy of telephones. We’ve got really good people working for us and they’ve been there for 25, 30, 35 years. And so, after that much time and experience with—I hate to use the word—the culture [of the gallery], they kind of know how we like to do things.

From Paris to New York and Hong Kong

I’m being a trifle New York-centric, but I wonder, who are these out of town shows for? How many people see them? Do they perform the same kind of public service that your—or anyone’s— New York galleries provide the city’s portion of the art world. Are there real art publics?

Yes, I think so, in every city. There’s our public in LA; there’s our public in Hong Kong and Paris. Paris has become more relevant for our business recently.

Thanks to Brexit?

Thanks, in part, to Brexit.

Your New York shows tend to draw large crowds. Do you check attendance at the various galleries elsewhere?

Not so much, but I do keep in touch with profit and loss. I don’t want just a bunch of vanity galleries that are all fed by New York. They basically have to justify themselves in terms of P and L. They have to run their own books, so each one can tell me how they’re doing.

There must be instances where loss exceeds profit.

We had two galleries we shut down because it was a mistake to open them, and I recognized it pretty quickly. San Francisco was one of them.

When loss exceeds profit

I wanted to ask about that. It opened across the street from—and in tandem with the reopening of—the newly expanded San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. And was never heard from again.

That was a super annoying situation. I had someone working for me who was a smart and effective sales-person and who said they were really well connected in tech, who really wanted to help open a gallery in San Francisco. I let myself get worn down and said, “Okay, let’s do it.” And then I’d go to the openings, not all of them, of course, but a few, and there’s nobody there. So when you talk about people walking through the door, it was really disappointing. The location was not the problem; the city was the problem. And maybe that’ll change in the next few years, I don’t know, but I wasn’t going to wait around.

And where was the other one?

Geneva. That didn’t work either. Nobody showed up.

Looking at which Gagosian artists are showing in New York and which are showing in your galleries elsewhere, a clear hierarchy emerges. On occasion, the galleries outside New York can serve for what are basically out-of-town tryouts.

Like off-Broadway.

And you have something similar in town. The small gallery at Park and 75th also functions as a tryout space, as does the 21st Street location, at times, relative to the 980 Madison flagship.

That’s worked out well. Some artists say, “No way—I want you to represent me, but I want to start with a show at 980.” I say, “No, we’re not going to do it that way. We want to test the waters. We want to see if the relationship works, if there’s good chemistry, if we get along. If you don’t want to do it that way, fine—but I’m not going to always plunge straight into 980 Madison.”

You have two lists of artists on your website. One features around 100 artists the gallery actively represents with solo shows, etc. About a fifth of them are estates. Below that, a prompt says, “See All Artists,” which is startling at the bottom of such a long list. This second list includes everyone from the first list, plus many others—around 280 in total, including about 100 estates. In other words, it reflects a much broader swath of the gallery’s dealings and forms a kind of archive.

If you go on the website wanting to see what we’re active in—and what matters to the gallery—I sometimes wonder if it can feel a little too diffuse.

The first list doesn’t feel overly diffuse, considering how many galleries you have. But the second one is more intriguing—it reflects the full range of your activity. Take Eric Fischl, for example: you’ve never given him a solo show, but he’s appeared in a couple of your group exhibitions. Same with Jean Arp.

It seems very open, in a way—transparent?

It’s kind of self-aggrandizing, but it also maps out much of your involvement with art. It’s a great resource for everyone.

There’s a hierarchy in any gallery. Not everyone is Cy Twombly or Richard Serra. But I believe in being open to young artists and seeing what might happen. I like that approach. I don’t want to be limited. Matthew Marks, I think, is a genius in how he represents a very concise, distilled group of artists. It’s incredibly focused—but that’s just not how I’m wired.

It seems likely that most of your artists don’t hear from the gallery every month.

They may not be hearing from me directly, but they’re probably hearing from their liaisons at the gallery.

“I ran into someone on Madison Avenue with a sharp tongue who said, “You know why you got that Picasso so cheap, Larry? Because everyone hated the guy who sold it.” Worked out pretty well for me” – Larry Gagosian.

On average, how many artists is one person at Gagosian responsible for? How do you assign that?

I’m not sure how to quantify it. Some artists require a lot more time, energy, and engagement; others are more autonomous and pretty much run their own show. We’ve got about 300 people working for us. It’s the only way to manage this scale. I can’t cover all the bases myself. The horses are out of the barn in that regard.

When did you buy your first Picasso? And what was it?

It’s hanging in my dining room. I’m not sure it was the very first, but it was close. A beautiful Dora Maar portrait. It came up at Sotheby’s with a high estimate of $900,000. It was the last lot in the sale, and no one bid on it. I bought it for the estimate—$900,000. Today, it’s a $40 million painting. Afterwards, I ran into someone on Madison Avenue with a sharp tongue who said, “You know why you got that Picasso so cheap, Larry? Because everyone hated the guy who sold it.” Worked out pretty well for me.

You have been criticized for making art dealing a blood sport.

It’s rough and competitive; art dealers are a tough breed. But what gets to me is when people say I don’t love art. How could I possibly do what I do without caring deeply about it? There’s no way. Why would I put myself through it? There are far easier ways to make money. I’ve never met anyone who truly succeeds in this world without a real passion for the art itself.

Are you better at selling to private collectors or to museums?

Private collectors. I don’t have the patience for museums.

When did you first come to New York? Were you already an art dealer then?

No, I had nothing. I was still selling cheap posters. It was around 1975, and I came because I had a girlfriend living here.

And then you came back. The next time was…?

Around ’77. I bought a loft on West Broadway, right around the time I opened my first gallery in L.A.

That seems a little contradictory.

I realized that to be good at my job, I needed to spend time in New York—see what was happening, go to the museums, hopefully meet some artists, just get into the flow. And as it turned out, I fell in love with the city. Not long after, I knew I’d eventually move here for good. My first New York show was David Salle, right there in that West Broadway loft.

A knack for money-making?

I saw it. It might have been the first time I saw Salle’s work, I think. I remember standing in a bedroom of that loft—it was high up—looking at a wonderful Salle painting over the bed. Then I turned and looked down at the entrance to 420 West Broadway, way, way below. It was a vertiginous plunge. And in retrospect, it also felt like a target.

Just being there felt symbolic. It meant something.

You discovered your knack for making money before you got interested in art, back when you were selling posters.

Yeah, I was selling posters on the sidewalk, hung on pegboards, if you can imagine that. And it was all about making money. It was schlock. Maybe even a step below schlock. They were $15 with a frame, and I’d make about $10 on each one. That felt pretty good. I sold a lot of them. So from the very beginning—for better or worse—I was learning about art and the art world while also figuring out how to survive. I never separated the two. In some ways, I think it was a good way to start. Though I wouldn’t exactly recommend it.

But you’d already seen Twombly’s paintings in L.A.

At Nick Wilder’s gallery. He had a Twombly Blackboard show in 1968. I was blown away by the paintings. I really liked Nick, and we became friends. He was very open, and he let me sell things for him. I used to drive him to see his shrink—it became a regular thing because he didn’t have a driver’s license. He was a fascinating guy, and just talking to him helped me take art more seriously.

Twombly’s work quickly became one of the enduring artistic loves of your life.

He was one of those artists whose work immediately excited me, both to look at and to think about. At a certain point, he didn’t have a gallery, or at least not one that was really working hard for him. I wasn’t sure I was ready for an artist of his stature, but it turns out I was. His first show with me was in late 1989, and it was also one of the first at 980 Madison.

Tell me more about your involvement with Twombly.

We used to show Cy almost every year. At one point, word got back to me—no names, and I’m sure they meant well—that people were saying, “Larry just wants money. He’s driving Cy into the ground, making him paint.” And to some extent, it was true: I did push him to work. But, honestly, I take pride in that. If I hadn’t been his dealer during that phase of his career, always encouraging him and giving him a place to show, he might not have made all those late paintings. That may sound a little arrogant, but it became a kind of tradition: every time I opened a new gallery—Athens, Rome, Paris—we’d open with a Twombly show. It felt like good luck. And he loved it. He loved it because he got busy.

Cy Twombly and Larry Gagosian: From friends to allies

Very busy. You have given him 35 shows so far.

It’s amazing to think of all that work coming right at the end of a painter’s life. You know, like there was no slowing down or fading. It’s some of the most powerful late work I’ve ever seen from any artist in my lifetime.

Another early show I remember was in 1986 at your first New York gallery on 23rd Street: Andy Warhol’s Oxidation paintings. I’d never seen so many of them in one place.

Yes, that was the last painting show he had before he died. I remember being in the studio. I’d just started doing business with Andy, through Fred [Hughes], who was helping me. I’d go over there as often as I was allowed, have lunch with Andy, see what was going on, watch him paint—because he painted all the time. He was always working. One day, we were having lunch at Fred’s desk and I noticed a canvas rolled up in plastic.

I asked, “What’s that?” Fred said, “Don’t bother. Nobody wants those. They’re the Oxidation paintings.” I said, “Can we take a look?” We unrolled one on the studio floor—this huge, 10-meter piece—and Andy said, “You think you could sell these?” I said, “Yeah, I think I could.” That’s how it started. It was a different world then—completely. You could be spontaneous with someone like Andy.

There was a big 1962 Coke bottle painting behind Fred’s desk. I asked Andy, “Would you sell that?” He said, “I don’t know.” I said, “How much?” He said, “$200,000?” To that, I replied, “Okay, I think I can sell it.” Then, I called Si Newhouse, he came down to the studio, and he bought the painting. For me, that was pure magic.

I knew of the Oxidation paintings, but I don’t think they really registered until that show. It gave me a whole new perspective on Warhol— as a kind of Abstract Expressionist manqué.

Well, he made quite a few of them, but they never sold. Nobody wanted them, and they were rarely shown. I think Leo [Castelli] may have given them a show—or maybe it was [Alexander] Iolas. But after that, they basically disappeared. He’d given up on them commercially.

What qualities make someone a dealer?

There’s no single formula—one size doesn’t fit all. There’s Paula Cooper, there’s Hauser & Wirth, and there’s everything in between. I’m not sure how to answer that exactly. But I do think the most important thing is that you have to really love art. Without that, nothing else holds. In my case, I’d say you need to be competitive— which I certainly am—and you have to genuinely like artists.

To be a good dealer, you have to work hard, have drive. I never had a grand plan; I’ve always followed my instincts. Sometimes I got it wrong, but more often than not, I got it right. Still, it was never mapped out. It’s just not how I think. I just wanted to do more shows, with better artists— artists I found interesting. It’s a totally consuming job. It’s all I do and all I think about. So how did I get from A to B? I’m not sure I can give you a neat answer. It’s just been an organic evolution.

Basquiat, one of Gagosian’s loves

Another one of your loves is Basquiat.

Basquiat was a special case. You don’t come across an artist like that very often—someone doing some- thing you’ve never seen before. I was in my loft on West Broadway when Barbara Kruger called and asked, “Are you in New York?” I said, “Yeah—I mean, you just called me on my New York number.” She said, “I’m in a group show at Annina Nosei’s gallery around the corner. Why don’t you come to the opening?”

So I did—because Barbara invited me. Annina’s gallery had three rooms. [This was in the Prince Street space that later became Miu Miu.] The first one had some kind of geometric wooden sculpture. The next was Barbara’s work. Then I walked into the third room—and I had never seen anything like it. It was one of the most electrifying experiences I’ve ever had looking at art. I couldn’t believe how good it was. It made me physically vibrate. I’m not exaggerating. It was that powerful.

Then Annina walked out of her office, which was right next to the room and said, “Larry, what do you think?” I said, “These are amazing. I’m completely blown away.” She said, “Oh, you don’t know? This is Jean-Michel Basquiat.” I’d never heard the name. I’d never seen a reproduction. I had zero awareness of this artist. He was 20 years old. First thing I asked was, “What’s available?” She said, “Three aren’t sold.” I asked, “How much?” She said, “$3,000 each”—maybe $3,500. I said, “Would you let me buy all three?” And she said, “Sure, no problem.”

One of them was that great skull painting that’s now in the Broad collection. I should’ve held on to that one. But I sold it to Eli [Broad], and that painting is arguably Basquiat’s masterpiece. Some people definitely think so. I sold it for $80,000 and felt like I’d won the lottery.

It’s better than selling something and feeling ripped off.

I needed the money at the time, so I don’t look back. I don’t regret it at all. But Basquiat became a major part of my life after that. He and Twombly were the two artists who really lit my fire.

It’s interesting because their work is both very graphic in a certain way. Like all important painters, they invented a new way of making a painting, something close to writing.

There was nobody painting like Basquiat before Basquiat. Sure, you can mention the CoBrA school or something similar, but that stuff looks like crap now—[Asger] Jorn and all that. Basquiat was completely original. Artists like that don’t come along very often. I even offered to donate one to MoMA, and they turned it down.

You did? They did?

Yes. They finally got one, though, didn’t they?

“Basquiat was completely original. Artists like that don’t come along very often. I even offered to donate one to MoMA, and they turned it down.” – Larry Gagosian.

You also represented Brice Marden during the last decade of his life, but I hadn’t realized you’d been involved with his work for quite a while. You bought a painting before you even moved to New York, right?

I always liked Brice. He was one of the first artists I met in New York, and we became friends long before I was ever his dealer—we socialized for years. He knew I was interested, of course, but he was always with one gallery, then another, and then another after that. Still, he knew I cared about the work. I bought it, I lived with it, I placed it. And eventually, he decided to let me represent him. That was a great moment—for me, it meant a lot to finally work with Brice.

How did that happen?

It happened at my house in St. Barts. Helen and Brice were there for dinner. At one point, Helen said, “Come on, Brice, what do you want to say to Larry?” And Brice goes, “Well, yeah, I thought maybe… maybe we could do a show. I like your gallery in London. Maybe we could start there.” Then Helen jumps in—and I’m paraphrasing—she says, “Come on, go all the way. Sure, London’s great, but you also want to show in New York. You want to show in L.A. You want Larry to represent you.” And Brice just said, “Okay.” That was it. That was the conversation.

Helen was a tremendous force in his life, his work, and his career. I don’t mean that in a bad way—it’s just hard to imagine everything he accomplished without her.

That’s very true. Without her energy and her devotion.

And without her traveling and collecting and great eye for real estate, to put it plainly.

I was really happy to see her new paintings, too. I just went up to Tivoli last week and spent the day with her. Since Brice passed, her work has really blossomed.

Maybe that’s not so surprising.

She’s working at a larger scale now, and the paintings are really strong. She’s still using shells and things like that, though less than before—but she’s still working with resin, color, and that glossy surface. Some of the pieces are really, really beautiful.

Selling, exhibiting… and discovering artists

What aspect of your work has given you the most pleasure?

Selling is a thrill. Exhibiting is a thrill. Honestly, it’s all thrilling in different ways. I love selling big paintings— expensive, famous paintings. That’s incredibly satisfying, and it’s an adventure in itself. But what really excites me is being able to juggle all of it over the years—working with young artists, established artists, and estates, while also staying in the game when it comes to selling a Mondrian or a Cézanne. I wouldn’t want to stop doing any of it. What keeps me going is the way it all plays off itself— the shows, the deals, the relationships. It’s the whole thing that excites me.

Of the 20 or so Picasso shows your gallery has mounted, it goes without saying that the standouts are the blockbuster, museum-quality exhibitions, usually staged on 21st Street and overseen by the gentleman and scholar John Richardson.

The first one we did was Mosqueteros in 2009. Then we did The Mediterranean Years in London (2010), followed by Picasso and Marie-Thérèse in 2011. After that came Picasso & the Camera (2014), and then a show comparing Picasso and Françoise Gilot. And you know, the moment we finished one, John would immediately ask, “So what are we doing next?” He was relentless—in the best way. It reminded me a bit of working with Cy [Twombly]. People used to say, “Larry’s exploiting Cy,” or “Larry just wants money for his private plane.” But I’ll tell you—if I hadn’t pushed him, Cy wouldn’t have made a lot of those late paintings.

Maybe you were Helen to his Brice.

I’d say, “Come on, Cy, I’ve got a new gallery—let’s make it the opening show.” I don’t think that’s a bad thing, and I don’t think it’s unusual either. It’s like having an audience right there, waiting. He wanted to stay in the game. Opening new spaces with a show of his became a kind of tradition for us. He painted right up until the end. That summer—2011—I was in the south of France, and we spoke on the phone just a few days before he died.

He was on oxygen, fading, drifting in and out, shutting down, but he was still describing the next body of work he wanted to make. Then I got the call that he had died, and I flew to Rome for the funeral. Cy only painted when he had something to say—an idea he was chasing. When that happened, he’d go to the studio and work like a madman. Otherwise, he didn’t feel the need to paint. He’d travel, read—he’d live.

But things were percolating…

The traveling and the reading—that was the percolating. He never forced it. If he didn’t have something to say, he kept his mouth shut.

I think it was great that he had you.

It was even greater that I had him.

It’s just occurring to me—maybe this interview isn’t going to work. In a way, we’re mostly just talking shop.

But isn’t that the best part? I’m a shopkeeper, after all.

Lighting Director: Jodokus Driessen. Photo Assistant: Fyodor Shiryaev. Production: Michael Gleeson, John Nadhazi. Post: Stereohorse.