14

14

Fondation Louis Vuitton explores how Basquiat and Warhol’s collaboration became historical

In 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol began producing works as a duo, inaugurating a prolific four-handed production that would last two years. The Fondation Louis Vuitton presents until August 28 the extent of this exceptional and ultra-prolific collaboration of the two Americans, which definitively changed the course of their careers and their practice.

by Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 14 April 2023. Updated on 20 June 2024.

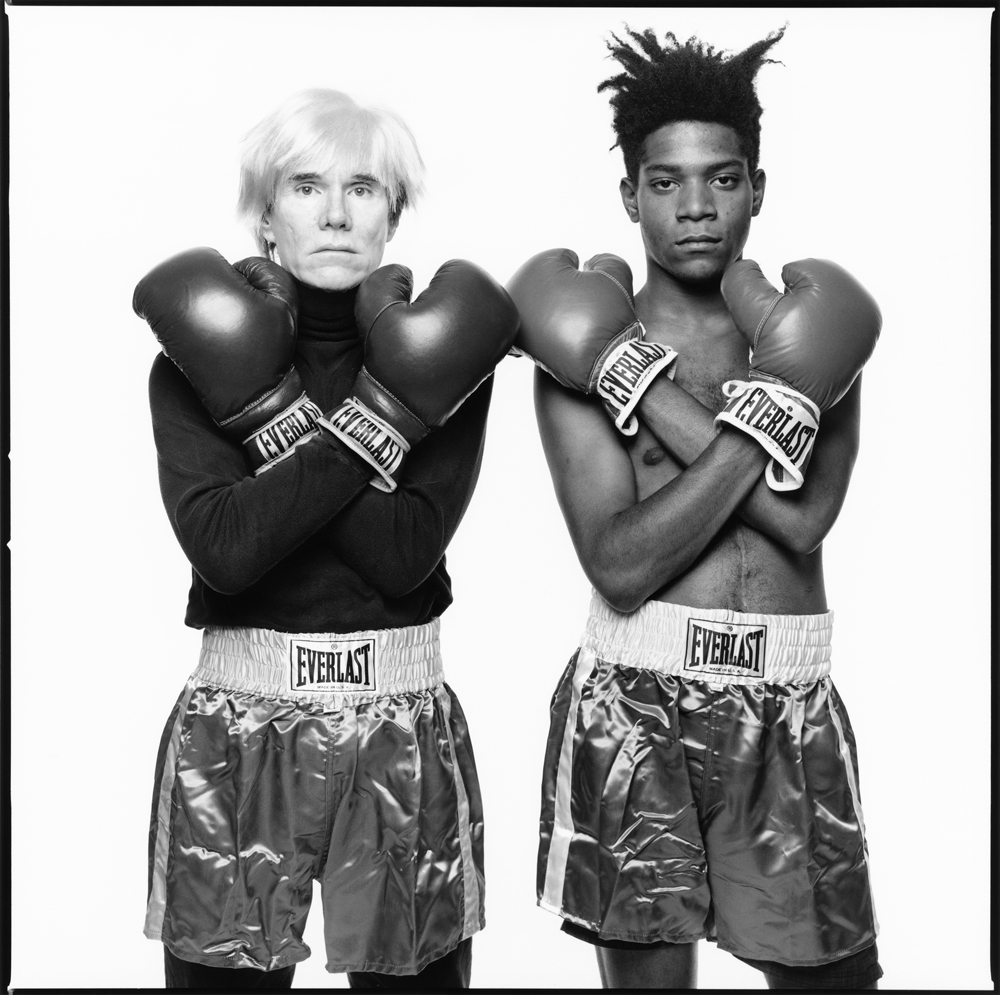

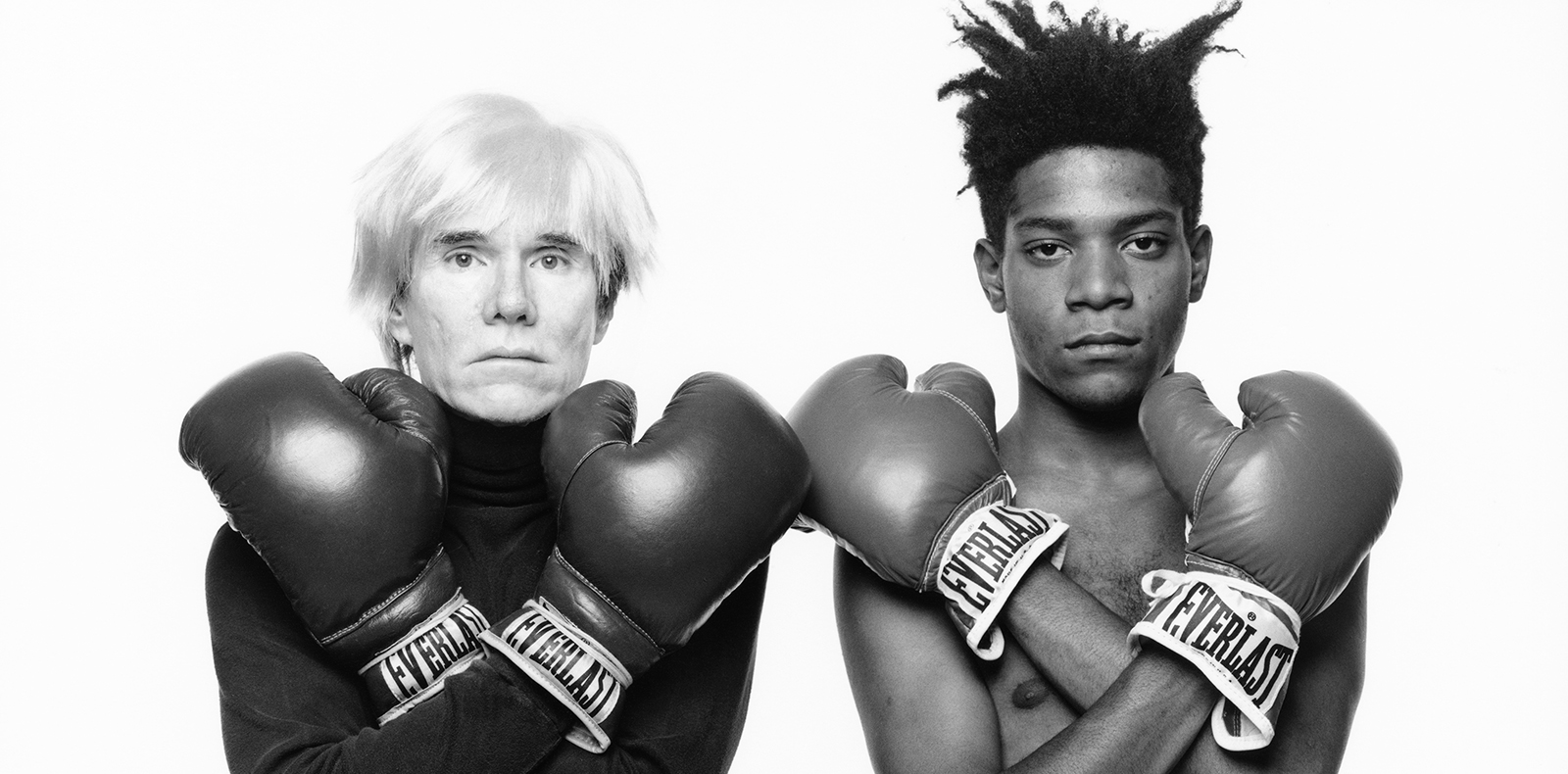

Standing side by side, their arms crossed with Everlast boxing gloves and shorts on, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat are set for a fierce match on the poster for the “Basquiat x Warhol” exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Rather than confronting each other, these two major figures of the New York underground art scene in the second half of the 20th century, here photographed by Michael Halsband in 1985, team up to face the visitors. A powerful way of introducing their prolific artistic collaboration, which began in 1983. For two years, the two artists produced around a hundred “four-handed” artworks, often monumental canvases that link together two complementary approaches and pictorial styles. Until the end of August, the Parisian institution will focus on this rich encounter through an exhibition of 300 works asserting how much this episode has marked the careers of both artists and the history of art.

Because it represents the unexpected encounter between two major artists

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) might never have met. In addition to a 32-year age gap, the two artists came from completely different backgrounds. The first one is a native of Pittsburgh, who graduated in fine arts and made his debut in advertising and shoe design in New York in the 1950s. The second one grew up in Brooklyn in the 1960s, raised in a family of Haitian origin, and started his career as a street artist under his now famous signature alias, SAMO. Although 1982 is often cited as the year the two of them first met over lunch, they had already met three years earlier. At the time, Jean-Michel Basquiat was only 17 and spent his days calling on passers-by in the street to sell his postcard collages. One day, he saw Andy Warhol with Henry Geldzahler, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in a restaurant in Soho. Basquiat, who admired Warhol, took matters into his own hands and approached them with two of his artworks, which they bought for $1 each. Although that moment was unforgettable for Basquiat, it wasn’t as memorable for Warhol, who remained rather dubious about the New Yorker’s potential over the following years.

The famous lunch on October 4th, 1982, brought about major change. That moment of passionate conversation set up by their common gallery owner Bruno Bischofberger immediately inspired the two artists – Andy Warhol immortalized Jean-Michel Basquiat with his Polaroid, before entrusting his camera to the gallery owner so that he could take a photo of the two of them. Jean-Michel Basquiat then left the two men before the end of th meal to work on a painting immediately afterward, which his assistant would come to present to them two hours later. In the now iconic portrait Dos Cabezas, the young man is depicted on the right-hand side with a smile on his face and a shaggy hair style against a blue background, while the thick lines drawing Andy Warhol’s facial features stand out on the left-hand side of the canvas. When presented with the artwork, the father of pop art admitted he was impressed by Basquiat’s speed and enthusiasm and would nurture a mutual admiration from that moment.

Yet, the conversation that sealed their artistic collaboration took place a year later on the other side of the Atlantic. While Basquiat was staying at Bruno Bischofberger’s place in St. Moritz, the gallery owner was amazed to discover the New York painter’s stroke on the drawings of his three-year-old daughter. A brilliant idea came up – to invite the young art prodigy, whom he had just begun to represent, to create artworks with other renowned painters, in order to allow his talent to shine through. When he presented the idea to an enthusiastic Jean-Michel Basquiat, the latter immediately mentioned Andy Warhol’s name. The project came at the right time to stimulate the latter, who, after a flourishing decade in the 1960s, was now more discreet, less daring, and mainly realizing portraits for celebrities and rich businessmen. The gallery owner also suggested Francesco Clemente, a great Italian painter close to Basquiat, as a third participant in the project. In 1983 and 1984, the three artists agreed to produce about fifteen pieces together. Their six-handed collaboration was launched.

Because it offers a new take on painting

Liquid bodies and spectral faces covered with frenetic strokes, symbols, sentences, and photocopied and silk-screened images… Basquiat, Warhol, and Clemente’s earliest canvases display a shape-shifting aesthetic, in which the plot and the protagonists are decentered and invade the whole painting. At a time when neo-expressionism was flourishing in the United States, the works of the trio were similar to those made by their counterparts Julian Schnabel, David Salle, and Enzo Cucchi, while differing from them in the multiplicity of techniques used and in their formal hybridity. By taking up the exquisite corpse process dear to the Surrealists and under the guidance of Bruno Bischofberger, the three artists contributed to its renewal by adding their personal touch. Each one of them freely took over a part of the canvas without informing his fellow artists of his intentions. They all waited for the last one of them to paint to reveal the final composition. Eclectic and composite, their pictorial vocabulary ranges from symbolism and fauvism to graffiti and advertising.

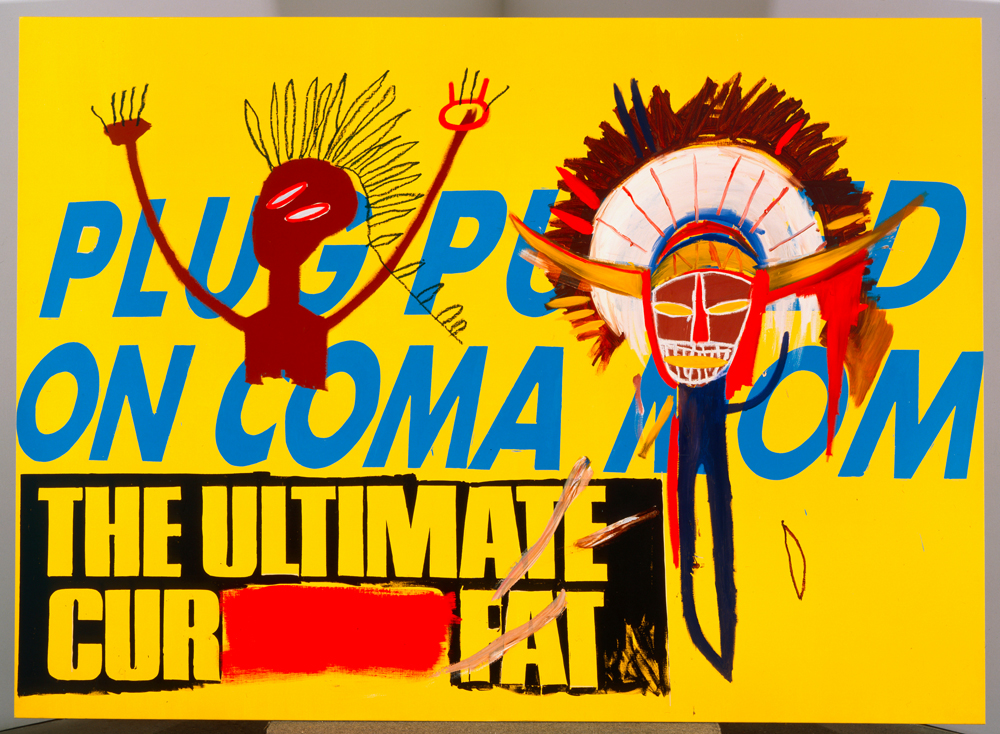

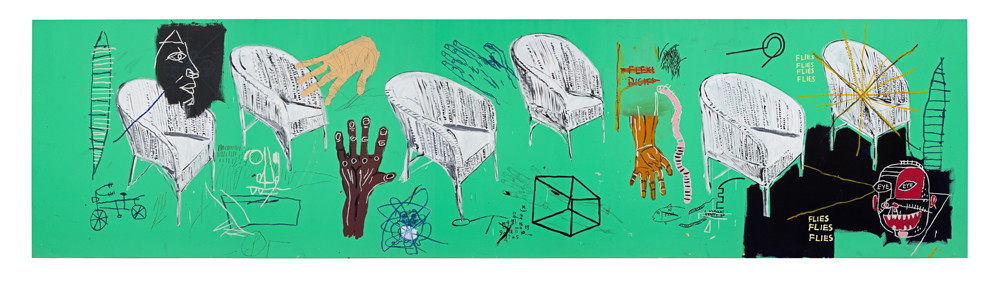

Stimulated by these pictorial exchanges, this six-handed work took new turn when Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat decided to extend their collaboration as a tandem. At the Factory, where the two painters produced artworks together this time, their stroke was freer as the formats of their canvases increased to 8 meters wide (Chair, 1985) and almost 3 meters high (6.99 and Mind Energy, 1985), further blurring the lines between fine art and mass visual communication. Unlike Francesco Clemente’s ghostly human figures, who invaded the early Collaborations and softened them with their more academic and symbolist touch, Basquiat and Warhol’s compositions expose large and empty areas of bright, plain colors to foster the expressiveness of their style. Here, the complementary nature of the painters prevails more than ever. As the artistic director of the Louis Vuitton Foundation Suzanne Pagé analyses it, the works combine the “raw and direct”, almost primitive aesthetic of the Basquiat, who himself recognized he was inspired by children’s drawings, and the “distance, even indifference, not without irony” of Warhol. Both men found their own pace to produce an extensive series of works. While Basquiat coated the canvases and painted them on the floor, Warhol took over the walls to create a variety the shapes that he would later add to the silkscreen.

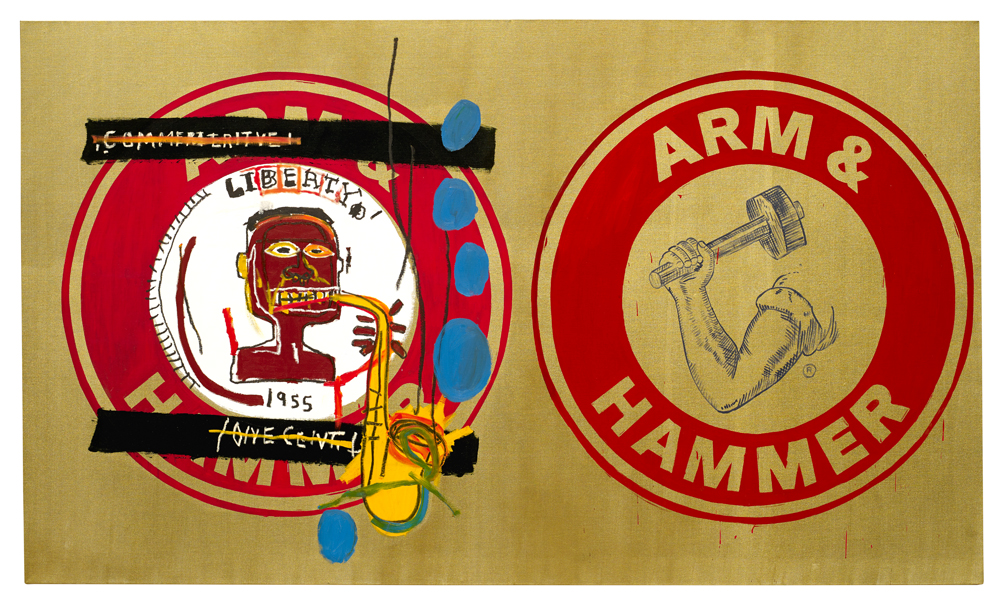

From one painting to the next, recurring elements arise. For instance, we find Warhol’s reproduction of the GE logo, from the American multinational energy company General Electric, and of the map of China, a country that had fascinated the artist for over a decade because of its culture, its president Mao Zedong, and the visual codes of communist propaganda. As a tribute to Warhol’s iconic album cover of The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967), in which a banana portrays the band, Basquiat regularly brings the fruit in the picture, along with African masks, to which the two painters devoted an entire piece in 1984. The two men often respond to each other with their respective interpretation of the same subject – Basquiat’s grinning mouth full of sharp teeth echoes to Warhol’s smooth dentures, while the lightning bolt logo of the electronics brand Zenith crosses paths with wild bodies unleashed by electric shocks. Opening the exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the artwork Arm and Hammer, named after the eponymous brand of cleaning products, explicitly shows that artistic mirroring with two juxtaposed subjects circled in red on a golden background – on the right-hand side, the muscular arm lifting a dumbbell with the brand’s logo on it was added by Warhol, while Basquiat signed the black face playing saxophone on the left-hand side of the canvas. Although the curves of the instrument echo those of the biceps on a formal level, the two elements offer two conceptions of masculinity above all. The smooth and organized appearance of the logo contrasts with the much more expressive, yet less structured character.

Because it marks a turning point in the careers of both artists

“When Basquiat and Warhol showed me their first collaborations – about forty paintings – it was incredible,” Bruno Bischofberger recalls. “I thought to myself, ‘they hid that from me!’” In the spring of 1985, the gallery owner was indeed surprised to see how his original idea had paid off, to the point that the two artists took it over without even informing him. When he exhibited around twenty of these works for the first time a few months later, the critical reception was almost unanimously negative. The quite radical approach of the young Jean-Michel Basquiat was still far from winning over the public, and the art institutions, which were “not yet ready” for him according to the gallery owner, were completely uninterested in the project. Only a few collectors saw the potential of the encounter between an established artist and his protégé. Basquiat, who was very sensitive, was deeply affected by the lukewarm reception of his work. He decided to put an end to his collaborations and to distance himself from his elder brother. More seasoned and used to criticism, Andy Warhol saw the limits of that collaboration when The New York Times described Basquiat as a “mascot” he had manipulated to gain that prolific production of artworks.

Although the two artists never worked together again after 1985, this episode in their careers gave a new and salutary impetus to their practice. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s mission, which was to give Andy Warhol a taste for painting, was accomplished. Lamenting on the end of their collaboration, the king of pop art confessed that the young man got him “into painting differently”. “Warhol was an old wild animal, but he became even wilder under the effect of his enthusiasm for Basquiat,” their gallery owner acknowledged as he witnessed the former’s new solo paintings as “collaborations” deprived of the latter’s touch. Basquiat, for his part, kept developing his silkscreen and ceramic practice following the same process he previously used with his idol and worked with other artists from the New York scene such as Keith Haring, Stefano Catronovo or Kenny Scharf on posters, vastes and even clothing. The two artists remained friends until they passed away in the late eighties, a year apart. Far from anticipating the huge posthumous success of their common œuvre.

“Basquiat x Warhol. À quatre mains”, until August 28th, 2023, at the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, 16th arr.