7

7

French artist Nadjib Ben Ali finds the raw material for his flamboyant paintings in football, rap videos and Hitchcock movies

Once again, Numéro art teams up with Gucci to showcase the young and promising talents of the French artistic scene. With a hunger for forms and colors, young French artist Nadjib Ben Ali finds the raw material for his flamboyant paintings in football, rap videos and Hitchcock movies.

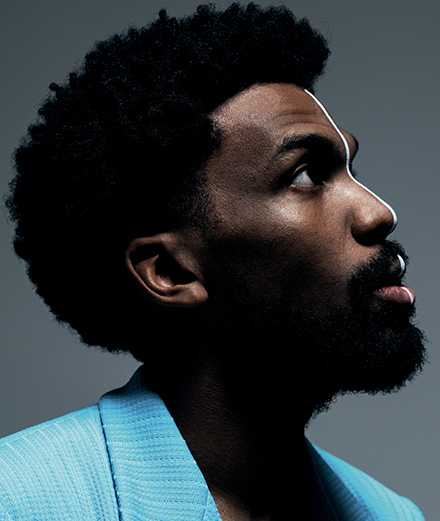

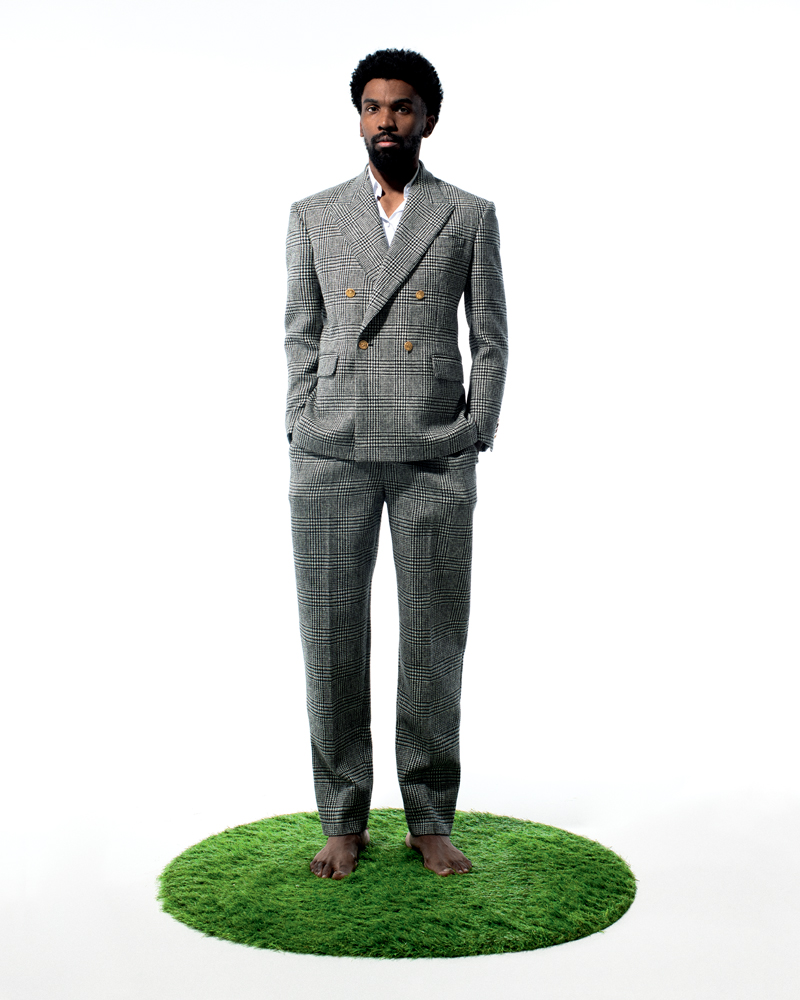

Portraits by Eva Wang,

Styling by Ferdi Sibbel Thibaut Wychowanok.

A “real image cannibal”

Nadjib Ben Ali is a football fan. But you can’t really say he watches matches; rather, he dissects them, like a critic scrutinizing an Alfred Hitchcock movie shot by shot. When he sees a frame he likes he takes a screenshot of it, which he then stores in a database to rival the Cinémathèque française. “I’m a real image cannibal, hungry for shapes, colours and compositions.” Some remind him of the master of suspense, others of Michelangelo. Hands touching, a close up of the back of the neck, a wide shot of a crowd. Legs intertwined. Faces marked by failure or victory. Ben Ali then compiles and reproduces these scenes as drawings – the physical manifestation of a virtual fantasy. If necessary, he reframes them, the spontaneous line of the marker pen giving them (new) life. Then comes the moment when they are transposed into paintings.

“My goal has always been to reproduce a marker-pen line in my painting.” To this end he invents his own tools: paint pencils made from glue sticks into which he inserts synthetic fabric (a soccer jersey, for instance). “For me drawing is like learning a choreography, memorizing a gesture that I’ll reproduce later on canvas.” Plunging his DIY pencils into acrylic paint, he mixes the pigments to recreate the brilliance of the screen on which the image first appeared. If necessary, he adds a little glycerol, “for a brighter black in the eye.” When he paints, Ben Ali looks as much to his drawing (for the materiality of the line and the gesture) as to the original image (for the composition). “But painting always wins,” he concedes. “I can change a colour, even if it is not identical to the screenshot or drawing because the balance of the painting calls for it.” Which he sometimes does to the point of abstraction.

A strong taste for dramaturgy

Ben Ali is not the first artist to take an interest in the dramaturgy of soccer. In 2006, Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon made Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, for which they filmed the soccer star with several cameras from different angles for the entire duration of a match. Every move was captured, alongside nervousness, indecision, indifference, solidarity and isolation. After 90 minutes, these fragments come together to form a whole, a vertiginous over-presence of a man, a dramatic hero. This same feeling of drama and dizzying wholeness is found in Ben Ali’s paintings. “I’m not interested in a particular soccer player but in professional soccer, the big sponsor ads, the spectators in the stadiums. I want to be in their place, I want it all to belong to me. I like the dramaturgy. Soccer players aren’t actors; they’re focused on the game and aren’t in control of their affects. Their weakness is exposed. I like this idea, them lying down, overwhelmed, wounded.”

An eclectic approach to painting

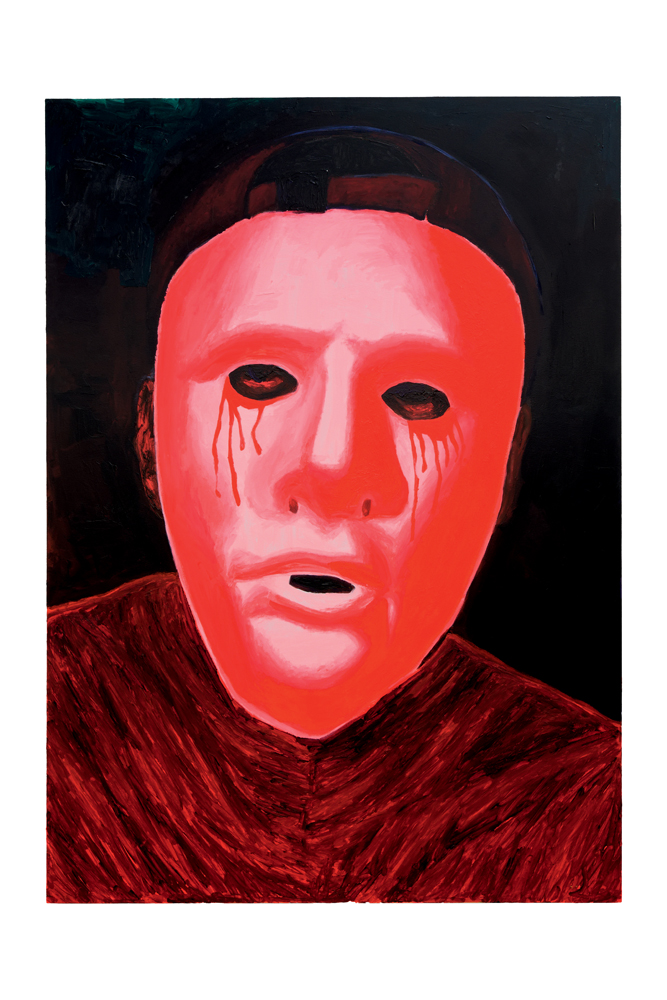

The artist has developed an obsession with necks, like the Dardenne brothers who filmed their actors from behind as way of showing a character in a weakened state. Viewers become voyeurs, stalkers with total power over their prey. In Ben Ali’s work, the nape of the neck becomes a source of eroticism, the viewer glimpsing a patch of skin peeking out between the hairline and the jersey. This fetish for body parts, and the clothing that dissimulates them, feeds an underlying homo- eroticism. Beyond Hitchcock, the movie reference here is Brian de Palma, another master of composition and patent fetishist (Pulsions, Body Double). One of Ben Ali’s recent canvases once again focuses on a face, but it is wearing the white mask of John Carpenter’s Halloween serial killer. The fluorescent red light that illuminates it against a black background radiates violence and absence; it is impossible to interpret the expression. Upon closer inspection, one sees the character is shedding tears of blood.

“My new Mixtape series is based on images that aren’t necessarily from soccer. The mask was worn by a young boy in PNL’s Simba video. Then I saw it again in another rapper’s video. I had my image: a bleeding world. Now I’m working on finding that light so specific to computer screens, more so than in my soccer series. For this I use fluorescent, almost phosphorescent colors. The whole thing is more Pop, very 70s.” It recalls the paintings of Nina Childress, the mode by turns figurative and abstract, exploring styles with a certain extravagance. Both respond to the question of how to turn an image into painting using multiple approaches: hyper-realist, almost to the point of caricature, combining classicism, kitsch, Pop art, bad painting and Abstract Expressionism. These stylistic deviations are in themselves a powerful commentary on the hierarchies within art and society – like finding Michelangelo at a soccer match.