7

7

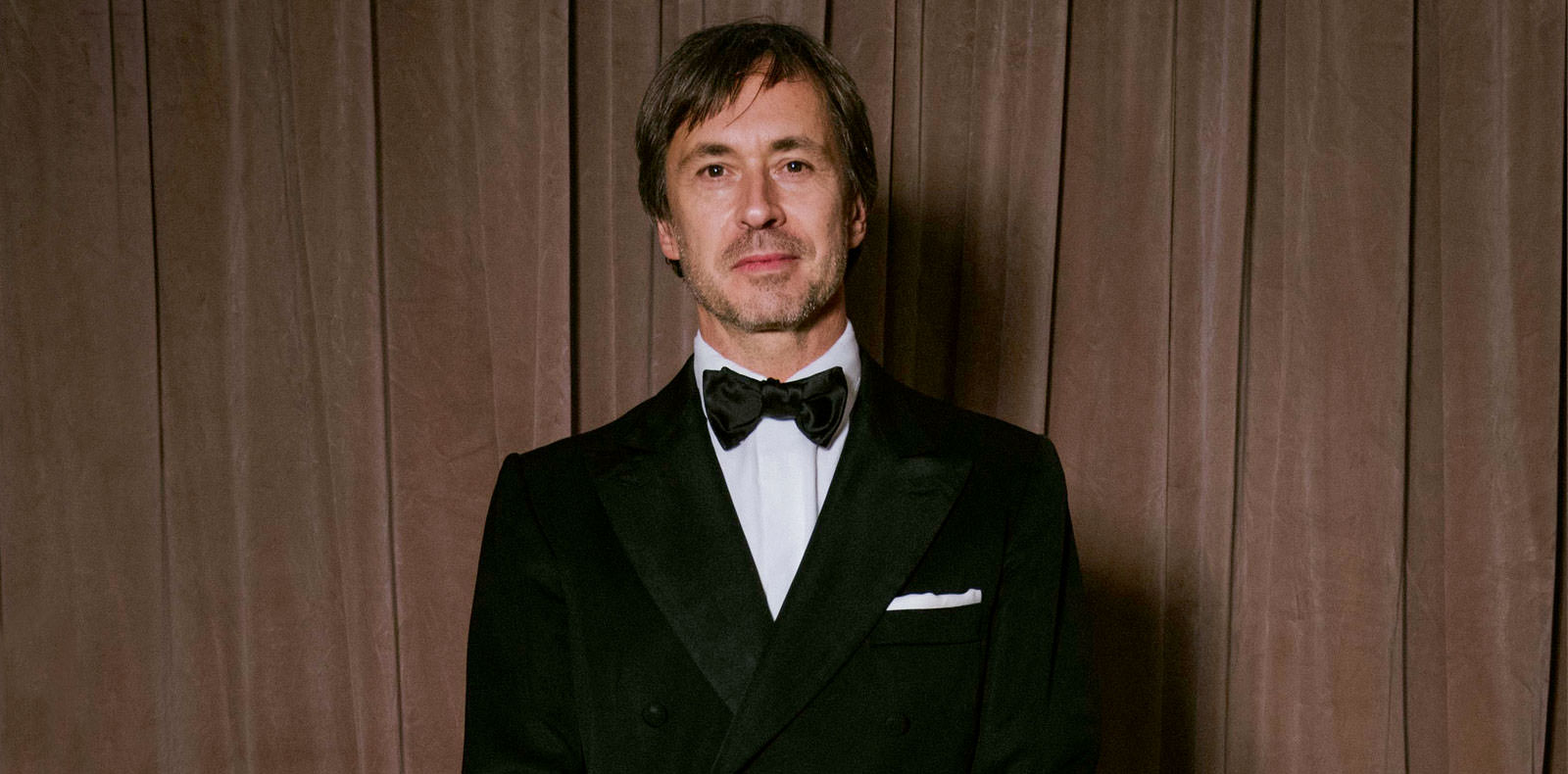

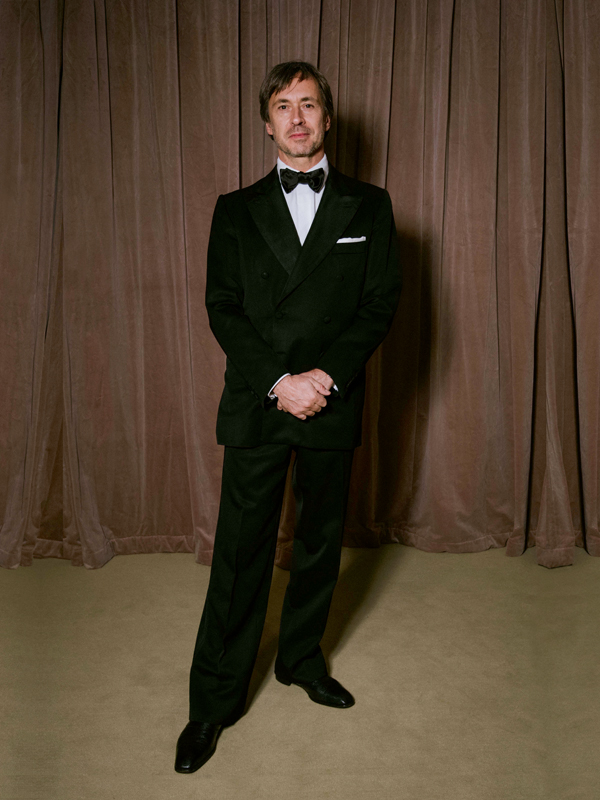

Confidences of Marc Newson: star designer

One of his early pieces recently sold for more than 1 million, a consecration by the market for a creator who, whether working on furniture, aeroplanes or watches, is always driven by the same passion for excellence. Numéro met him.

By Olivier Reneau,

Portrait: Ben Broomfield.

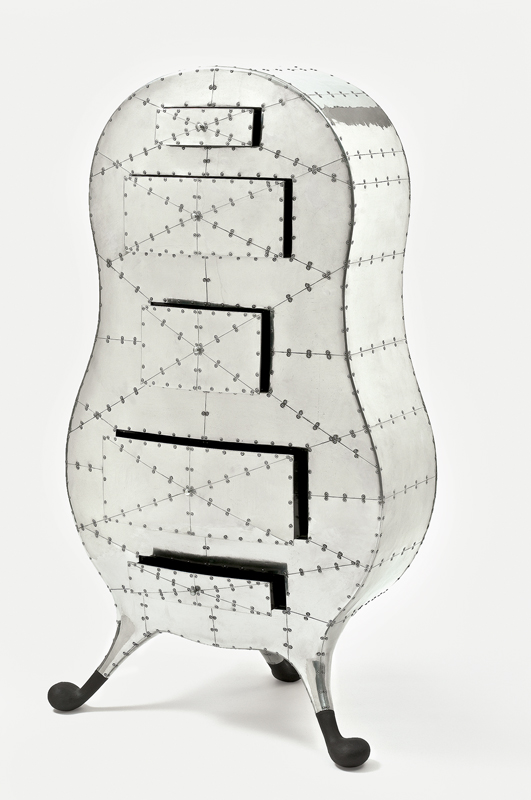

Australian designer Marc Newson made his mark on the international scene in the late 1980s with his fluid lines inspired by the worlds of skate and surf. Curious about the planet he lives on, Newson believes that his job consists in finding solutions to a particular problem, and that consequently nothing is beyond the designer’s remit, from everyday objects to one-off pieces of furniture, from interior design – of aeroplanes in particular – to watches, clothes, or the relooking of an iconic brand such as Riva speedboats. Over a 30-year career, Newson has earned a réputation as a larger-than-life figure, an all-terrain “super-designer” who can intervene with ease in every aspect of contemporary culture. Last October, one of his oeuvres de jeunesse, Pod of Drawers – a stylistic digression in riveted aluminium plates that was inspired by a 1920s chest of drawers by André Groult – was sold at auction house Artcurial for the previously unattained sum of over E1 million. For Numéro, the Australian prodigy, who is today based in London, talked about his approach to design and his ability to undertake a highly diverse range of projects, which always result in an exceptional object – as though he had the power to transform everything he touches into gold.

NUMÉRO: In Paris at the end of October your Pod of Drawers sold at auction for over E1 million, a price that confirms that your work now dominates design sales. How do you feel about this enthusiasm for a piece from your early days?

MARC NEWSON: I’m really not the person who could tell you what makes the difference between my work and other people’s! As for the reasons for such high prices, let’s just say that in the art world people don’t exactly object to the price of the works. Moreover it should be remembered that 50 or so years ago the decorative and the fine arts were considered very similar – the great schism only happened recently. But where the art market is concerned, the level of speculation is astonishing – you might just as well be investing on the stock market! I’m very happy that my work is appreciated, particularly because, in most cases, my limited editions were an opportunity for me to undertake technical experiments that I couldn’t otherwise have done. For me they remain essential creative exercises to the extent that, unlike my industrial commissions, I worked on them without a brief and was therefore free to fix my own parameters. But pieces like Pod of Drawers then go on to have a life of their own; each has its own personality which seems completely detached from mine.

For ten years you designed clothing for G-Star Raw. Is fashion different because it’s ephemeral?

Fashion, music and film are among the creative fields I want to remain open to. This openness is an essential source of inspiration for my work. I like to know what’s going on around me, particularly with respect to architecture. As for fashion, it’s simple: I wear clothes, so I want to be able to design what I wear. But that doesn’t make me a fashion designer or a couturier – I don’t claim that title at all. With clothes, I’m just experimenting in another creative domain, just as I’ve done with cars or watches… It’s always exhilarating to go beyond certain limits. To my mind an industrial designer must be capable of that. I’m often asked how one person can design a watch, a plane, a pair of shoes… But for me it’s simply a question of logic and language applied to objects which, from a technical point of view, are not so different. The challenge is more or less the same. If you call yourself a designer, you have to remain aware of popular culture, take the pulse of society, otherwise you’ve no legitimacy or pertinence. I really liked working for G-Star Raw, it was a very natural collaboration. In the fashion industry, the process from design to manufacture is very fast, whereas in industrial design it sometimes takes up to a year or even more before your pieces are realized.

You seem to love everything that flies – jets, spaceships and even one-man flying machines. When did this passion begin?

Long before I knew what they were about in terms of materials and technology, I adored the speed, aerodynamics and intrinsic beauty of planes. For me air travel was the best way for an ordinary person to have an extraordinary, “out of this world” experience. My dream was one day to jump in my own private plane for a quick jaunt somewhere! In Australia, where I grew up, some of my friends learned to fly before they le a r ne d to dr i ve – in the Outback, for example, to go from one sheep farm to another. Gliding was also a very popular sport. So none of these ideas seemed like a complete fantasy.

Would you say that your work as a designer is sometimes more a question of artistic direction?

I’m purely and simply a designer. That describes what I do: I solve problems

How do you approach luxur y brands like Riva, Beretta, JaegerLeCoultre or Louis Vuitton?

From a design point of view, I don’t see a fundamental difference between a car, a watch, a bottle opener or a boat… To be honest, while a car involves greater complexity, a bottle opener can turn out to be more technical because new types of plastic and polymers are currently being developed which offer some quite radical possibilities. But when I work with a brand that has an iconic side to it, I never lose sight of the fact that you have to respect its DNA. My work consists in mixing the brand’s DNA with mine in the hope that the final result will be as beautiful as it is innovative.

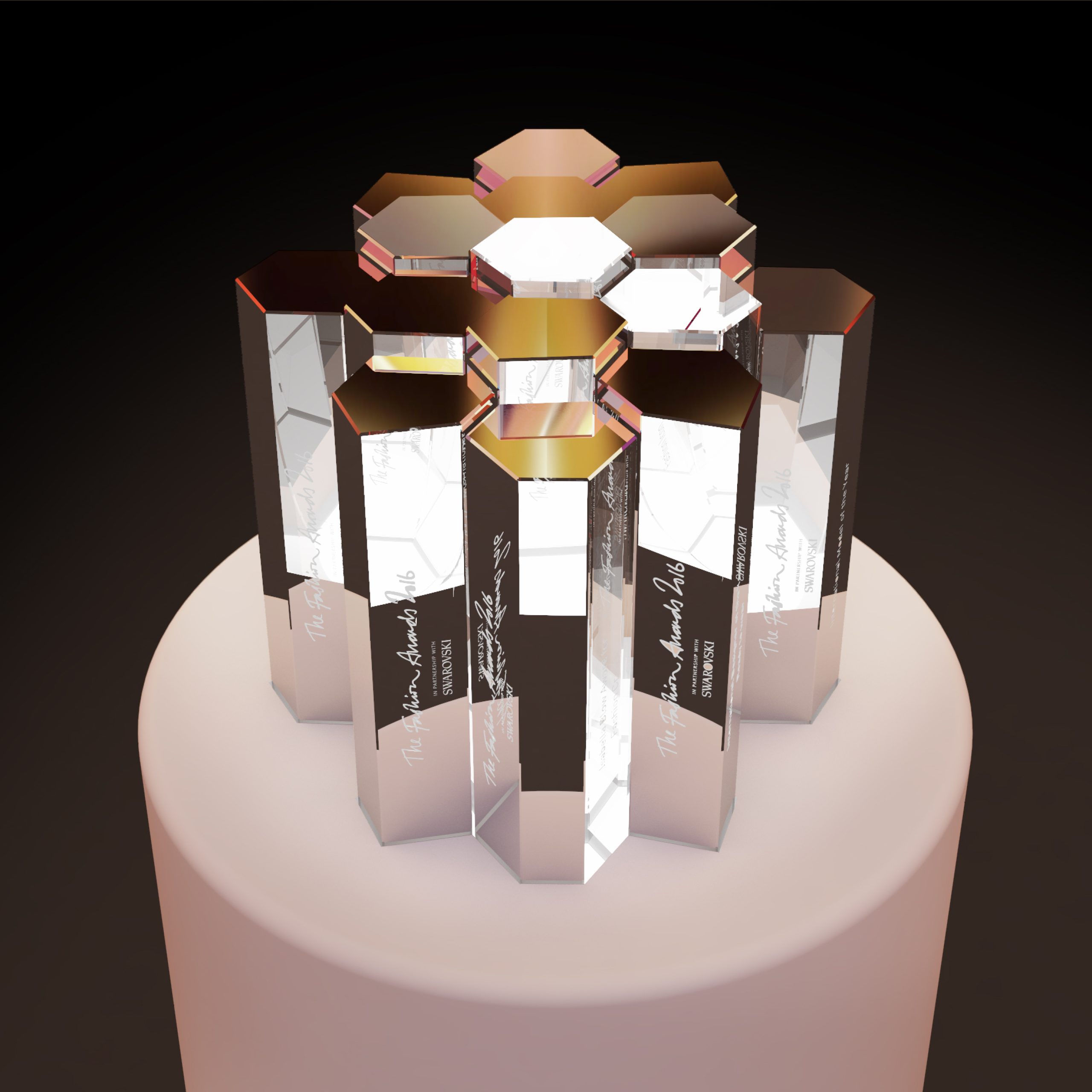

With Swarovski you’ve just designed the trophy for the 2016 Fashion Awards. Was this the first time you worked with this firm and/or with crystal?

Even if up until now we had never worked together on any kind of commercial project, I’ve known Nadja Swarovski for many years. So for me this was a fantastic oppor tunity to work with cr ystal, which is a fascinating material.

What makes an object without a function, like a trophy, different from a functional object like a drinking glass?

Ah, but on the contrary, a trophy like this has several functions: it has to be spectacular, it must express dynamism, and it must feel solid when you pick it up. In this particular case, the trophy also had to be divisible, in a simple and efficient way, into several individual trophies. Having said that, at the end of the day it was first and foremost a question of design, and that’s my profession. Each project has specific design problems that have to be solved.

Is there a type of object you’ve never worked on that you’re dying to have a go at?

There are loads: a train, a fridge, a swimming pool… The level of design for so many things is scandalously bad, and I’m itching to find replacement solutions. But what I’d like to design more than anything is a space station.

MORE: Portfolio: "Here, There, Nowhere" exhibition at Carpenters Workshop Gallery

WE RECOMMEND: Beyoncé invites R'n'B duo Chloe x Halle and singer SZA to join her for Ivy Park

![Horsphère Bois (III) [1967] de Jean Degottex (provenance : Galerie Jean Fournier, Paris). Huile et grattage sur panneau, 120 x 80,4 cm. En bas : console-table (1902) de Carlo Bugatti. Bois laqué noir, cuir, métal et incrustations d’os, 70 x 116 x 70 cm. Ensemble présenté sur le stand de Sceners Gallery. © Courtesy of Sceners Gallery.](https://numero.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/pad-london.jpg)