6

6

7 contemporary artists who give ceramics a new breath

At a moment in time when contemporary artists all seem to be mad about ceramics, Numéro art has selected seven of them whose work stands out from the crowd, contradicting dominant trends.

Photos by François Coquerel,

Text by Nicolas Trembley.

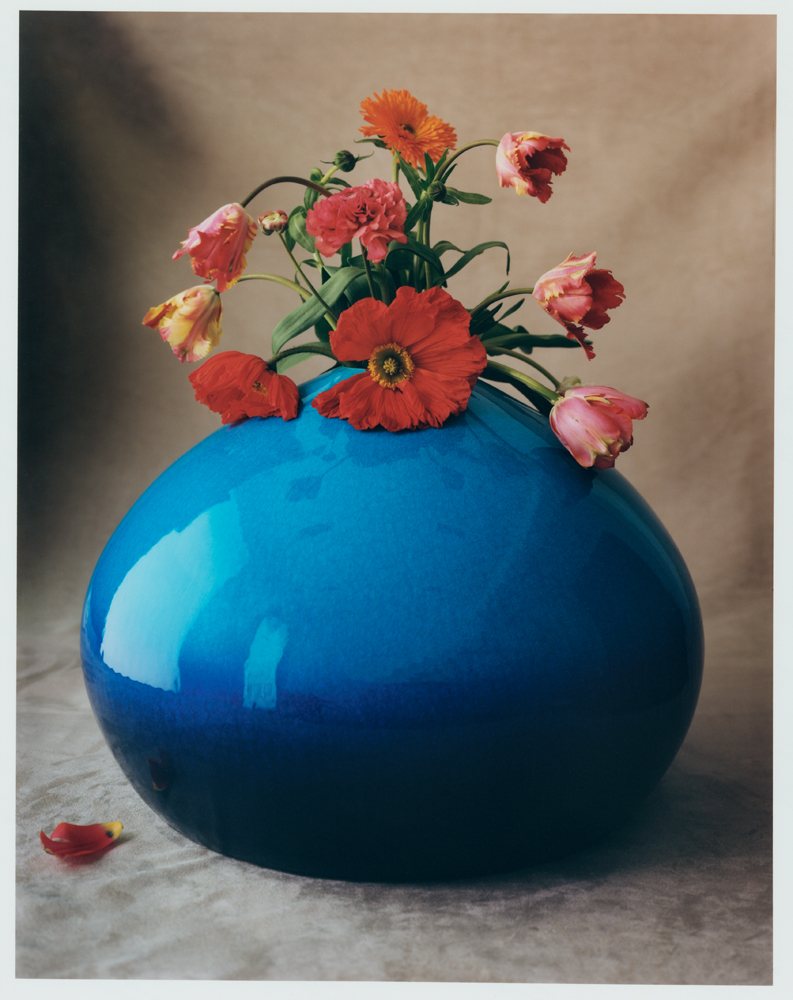

1. Yoshiro Kimura

Yoshiro Kimura was born in 1946 in Japan and works in Hiroshima. He had no intention of taking up ceramics, his first ambition being to become a Buddhist monk. After his studies, he began to travel the world, and it was during a trip to Europe, and more particularly while crossing the Aegean Sea, that he had a revelation about the different shades of blue in its waters as they reflect the Mediterranean sky. Blue, a colour historically used in Chinese porcelain from the Ming and Qing periods, became a nodal point in his practice. Kimura’s interest in all things Zen can be felt in his production of simple, minimal forms expressed as vases, bowls and dishes. The centre of his objects is often emphasized with a dark colour that resembles the famous cobalt of ancient-Persian ceramics, and then gets lighter and lighter towards the edge, culminating in a rich celadon. These variations are found in his vases, which are dark at the base and become progressively lighter towards the top. Kimura uses a traditional Japanese blue-glaze technique known as hekiyu, which he mixes with a decorative ripple technique called renmon. He has received many prestigious Japanese and international awards, including the Tanabe Museum Excellence Award and recognition at the first International Ceramic Biennale in Korea.

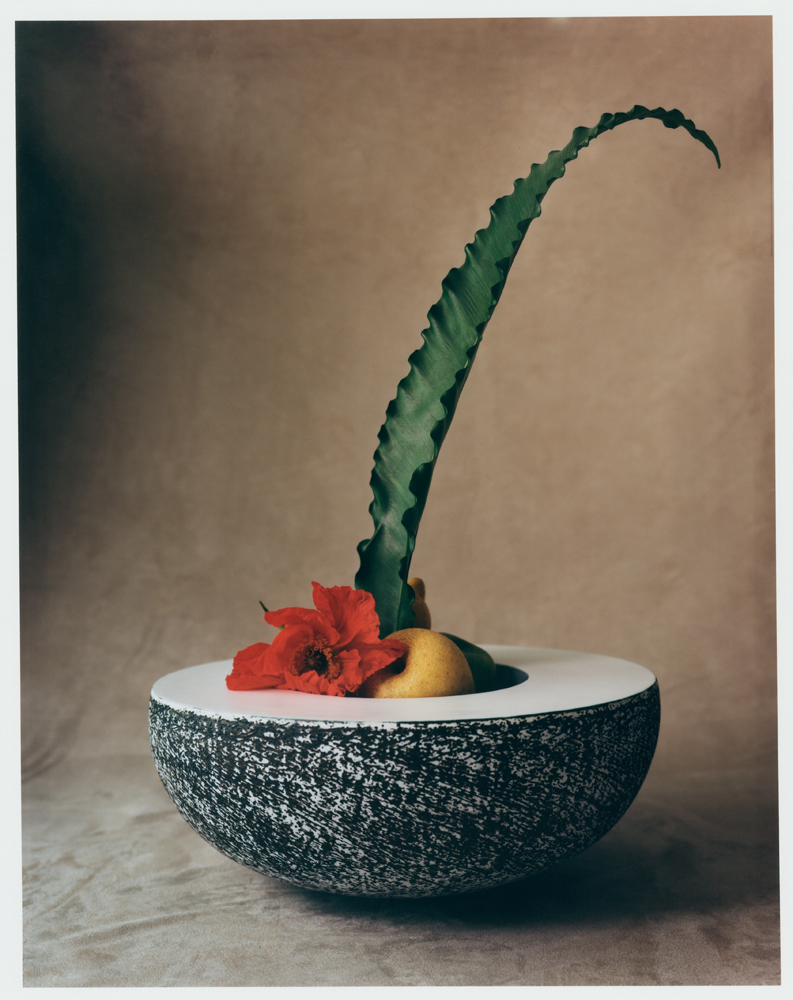

2. Kristin McKirdy

Kristin McKirdy developed her culture through her travels back and forth between France and the United States. She studied at Parsons School of Design in New York in the late 1970s and completed a master’s degree at UCLA in the early 1990s. She went on to do a master’s degree in art and archaeology and wrote her thesis on the history of modern ceramics at the Sorbonne. This dual training as an artist and art historian provided McKirdy with a profound knowledge of forms and enabled her to develop a sculptural vocabulary far removed from any “domestic” function. Her pieces, with their archaic and anthropomorphic forms, refer to the techniques of the earliest Mediterranean civilizations, and she often uses tools found in antique shops to create them. McKirdy’s ceramics, which are initially thrown as basic geometric volumes, are afterwards enhanced with various coloured additions in soft, round organic shapes that, she says, are reminiscent of candy. Playing with surface contrasts, she will often rough up or scratch her outer surfaces, while the inner glazed parts are rendered milky smooth and shiny. Some of her sculptures seem to have been cut in half, like fruit, and are displayed in groups, at times in the form of a screen and at others hung directly on the wall.

3. Akiyama Yo

Akiyama Yo is a pioneer of ceramics in post-war Japanese art history and is regarded as one of the most important figures in contemporary art. He is one of the heirs to the Sodeisha movement (1948–88), whose philosophy was founded on the refusal to copy objects from the past all the while distancing itself from the then dominant Mingei movement, which advocated a simplicity of form. Yo con- sequently eschews the classic small bowl in favour of massive sculptures that can measure up to dozens of metres in height or length. There is a primitive aspect to his practice and his relationship to clay, which he doesn’t throw but leaves almost in its raw state, as well as refusing to glaze his works, in defiance of Japanese tradition. He is a master of kokuto, also known as “black fire”, a process in which carbon-impregnated clay is fired at low temper- atures and is blackened on its surface with soot, giving it the appearance of charred wood. To obtain his effects of cracks and breaks, he uses a clay that is low in malleability and consequently difficult to handle. He likes to say that he seeks to “give form to clay and then destroy that form.” His works can be found in all the world’s major museums, such as London’s Victoria & Albert.

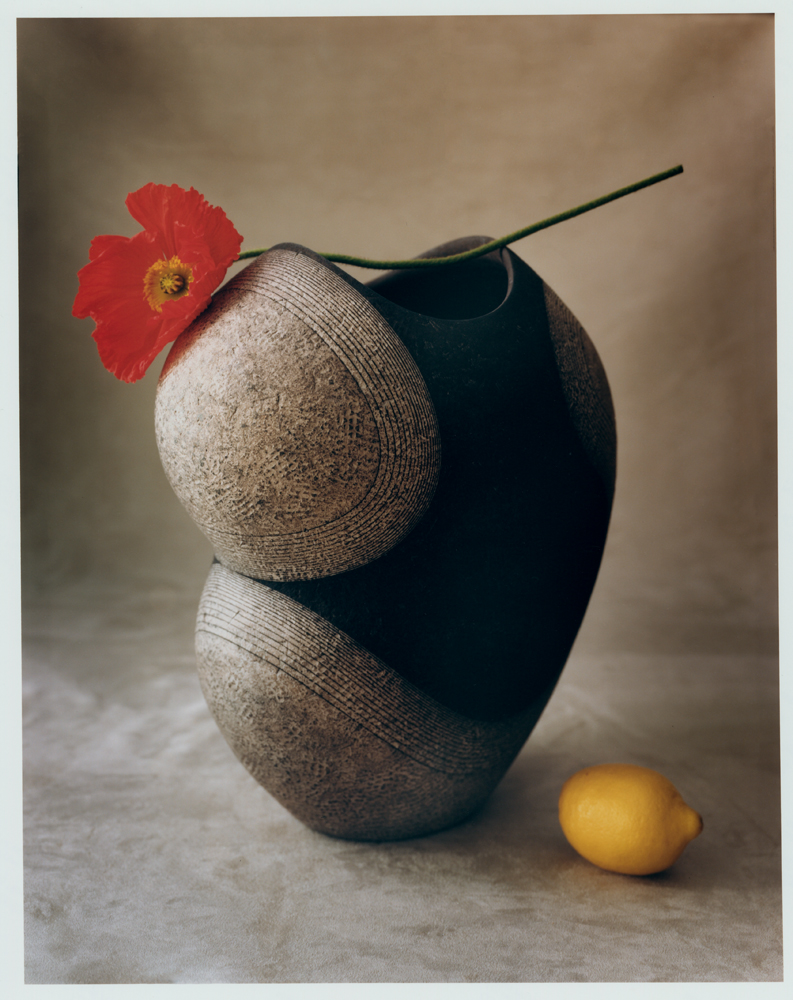

4. Daisuke Iguchi

Daisuke Iguchi was born in 1975 in Japan and, after studying at university and the Mashiko Pottery Institute, returned to his native Tochigi to set up his own workshop where he draws inspiration from the potters of the Yayoi period (400 BCE–300 CE), who produced a new type of Chinese-style ceramics, as well as iron and bronze objects. What is particularly striking in Iguchi’s work is his loyalty to a palette made up of shades of grey, reminiscent of pebbles and burnished or oxidized metal. His signature surfaces are the result of extensive technical research and a complete mastery of the firing process at different tem- peratures, as well as the use of ash in the manufacturing process. Once they have cooled, he works the surface of each vessel with a wire brush to obtain a lightly textured effect, producing a very particular finish that defies tradi- tional ceramic conventions. Then, using thin masking tape, he creates geometric patterns with a silver glaze, often in the form of sinusoidal lines. His extremely elegant sculptures, with their soft, curved forms, appear timeless, engendering a feeling of contemplative harmony close to the sacred, as though they had come down to us from an ancient civilization.

5. Takuro Kuwata

Takuro Kuwata is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating ceramicists on the contemporary Japanese scene. Born in the early 1980s in Hiroshima, he first studied the traditional techniques used to make the famous tea-ceremony bowls, but soon began to disrupt, deregulate and move beyond these classic codes to produce spectacular sculptures that are reminiscent of computer-generated 3D images. Kuwata makes his own pigments for his glazes, which are extremely complex, and are obtained using ancestral techniques such as kintsugi, a gold-powder lacquer-based method of repairing broken porcelain. In a similar way, he practises kairagi, a method that involves applying several layers of white glaze, or shino, which produces a more orange-hued result. His experiments with firing times and temperatures leave ample room for chance. Sometimes his works are blistered by ishiaze, a technique that consists in deliberately leaving small stones in the clay that explode during firing and deform the surface of the objects. His “bowls,” produced in a range of show-stopping colours – silver, blue or red –, and which appear to have melted, are so extraordinary that in recent years they have become highly sought after, his work often being exhibited in galleries as a form of sculpture.

6. Sterling Ruby

While the porosity between craft and contemporary art has not always been accepted or understood, artist Sterling Ruby has become one of the most accomplished ambassadors of this kind of cross-over practice, which allows him to free himself from the presuppositions of specialization. Painting, ceramics, sculpture, collage, drawing, textiles and even fashion collections – everything has inspired this 1972-born jack-of-all-trades, who works in Los Angeles and is as much at home with epoxy resin as he is with bronze. Ceramics are also very much part of his craft culture, which he acquired when still a teenager, long before he received any formal training as an artist.

Ruby’s ceramic pieces, in which he frequently seeks to defy conventional technical limits, are finished in ultra-shiny glazes that are reminiscent of the famous post-war German “Fat Lava” pottery that his mother used to like to collect. He pushes classic firing processes to the extreme, and knows exactly how and when to manipulate them. “I know what clay to use,” he explains, “what proportion of cham- otte [a type of calcined clay] to include, how much a piece will shrink, what role a brick and the different parts of the kiln play, how to control convection and air circulation during firing, how temperature affects colours and how some pieces will inevitably explode.”

When an explosion does occur, all is far from lost: the broken pieces can be reused and combined in new works, often with other – frequently organic or primitive – shapes, forming giant ashtrays or flowers, which he sees as a kind of fantasized archaeology. Paris will soon have a chance to admire the results of his labours, since Ruby’s work in clay will be included at a major exhibition on ceramics, entitled Les Flammes, which is scheduled to open at Paris’s Musée d’Art moderne in October of this year.

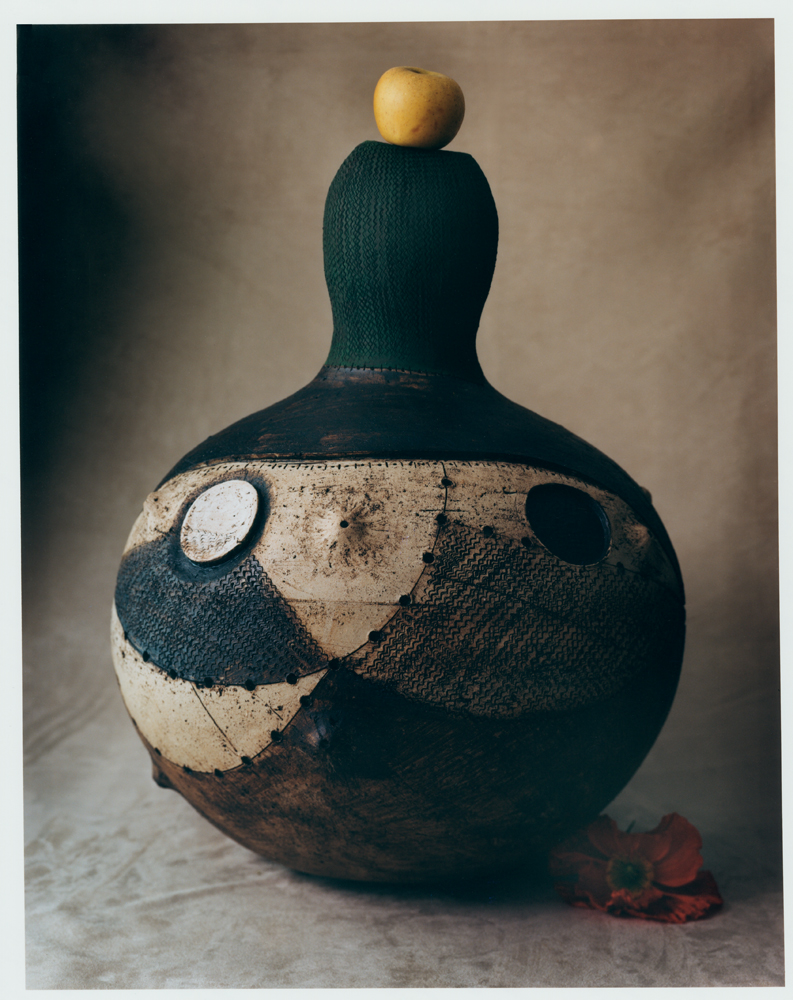

7. Simphiwe Mbunyuza

Contemporary African ceramics have not always enjoyed the same visibility as those from other parts of the world, such as, for example, Southeast Asia. Perhaps too often associated with the traditional daily life of the different local populations, African pieces, whether household crockery or funerary jars, are made by hand, generally by women, who do not use a potter’s wheel. In recent decades, however, a new generation of artists has emerged, bringing new perspectives to the medium. Born in 1989, Simphiwe Mbunyuza grew up in South Africa in a village close to those inhabited by the Xhosa people. His large-scale sculptures are often reminiscent of a calabash, a cucurbit that serves as a container or soundbox for certain African musical instruments. Mbunyuza’s richly textured works are made of materials as diverse as stoneware, leather, fabrics and even steel. He juxtaposes all these different components by borrowing from the Xhosa their centuries-old ancestral “colombin” technique, which consists in superimposing small balls of clay to make up larger-scale pieces, to which other parts can be added in various different materials. With their patchwork of techniques, Mbunyuza’s works pay tribute to the old African traditions, all the while resolutely projecting them into the world of today.