21

21

Diana Campbell curates two biennials inspired by the broken heart

For the past 15 years, Diana Campbell has been promoting a more inclusive and less Western-dominated vision of art, initiating dialogues between under-represented artists and more acclaimed figures. Bringing together established and emerging scenes, this brilliant curator is currently planning events in Uzbekistan and Bangladesh that take as their theme the trials and transformations of heartbreak.

By Diana Campbell.

Published on 21 November 2024. Updated on 2 December 2024.

Diana Campbell draws inspiration from broken hearts in contemporary art

“Don’t ask me for the same love my sweetheart I thought that life was radiant because of you Why complain of worldly woes, once in your love-affliction Your countenance brings eternity to the youth of spring What else is there in the world but for the beauty of your eyes If you were mine, my destiny would surrender to me […]”

Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Pakistani poet

These words by the Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz could not resonate more for me, even though I first read them 40 years after his death. The way the world feels today, any romantic kind of heartbreak I may have known in the past seems trivial given the much bigger heartbreaks that exist on a planetary scale. In my curatorial practice, I’ve been thinking a lot about heartbreak recently, and about the role art can play in healing a broken heart. My project Recipes for Broken Hearts will open the first edition of Uzbekistan’s Bukhara Biennial on 5 September 2025 – an event organised by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation.

The first Bukhara Biennial in Uzbekistan

Interestingly, Faiz Ahmed Faiz also visited Uzbekistan, in 1958, co-founding the Afro-Asian Writers Movement in Taskent. While working on this biennial, I’m also building the seventh edition of the Dhaka Art Summit, which responds to the heartbreak expressed by a young visitor to our 2023 edition, who wrote messages on our walls to a woman named Tondra, such as “Everyone is here, but you are missing from my life.” Furthermore, I’m a member of the facilitation group of AFIELD, an international network of socially engaged artistic practices that supports creative practitioners who try to heal societal heartbreaks. Their artist-led initiatives battle many forms of injustice around the world. Refusing to capitulate to heartbreak, all these projects seek to allow learning and healing by transforming past the breakage.

The heart, a complex instrument

Recipes for Broken Hearts looks at a complex instrument in need of constant maintenance as it beats over the course of a lifetime. More than a physical organ pumping blood, the heart functions as a locus of identity and loss, connecting the mind, the soul, and the body and bridging the material and spiritual worlds. The heart’s pervasive awareness means that we feel it breaking with extreme intensity.

From climate change to conflicts and polarization, many of our environments are teeming with heartbreak. But, like any form of rupture, heartbreak can be a dynamic space for transformation. It is one of our greatest teachers, a universal experience that can be felt both individually and collectively and that links us to all times and places, especially through creative expression.

Gulnoza Irgasheva, Sanam Khatibi: when artists tell the story of separation

The Uzbek artist Gulnoza Irgasheva and the Belgian artists Sanam Khatibi and Miet Warlop are among the people with whom I’ve been thinking through ideas of personal heartbreak. In her 2023 film Devordagi Bolalik Suratim (My Childhood Photo on the Wall), Irgasheva takes us into a relationship falling apart. The artist and her former partner used the camera and phones to share their intimate stories over 30 days, working across different formats and viewpoints. Based on a true story, the video follows the relationship between the two protagonists as it unfolds against the backdrop of cultural differences and the pressure of family expectations. Through candid conversations and meaningful pauses, the heartbreak of their separation is expressed ever more poignantly, leaving the viewer with an intimate sense of belonging and a profound awareness of unspoken implications.

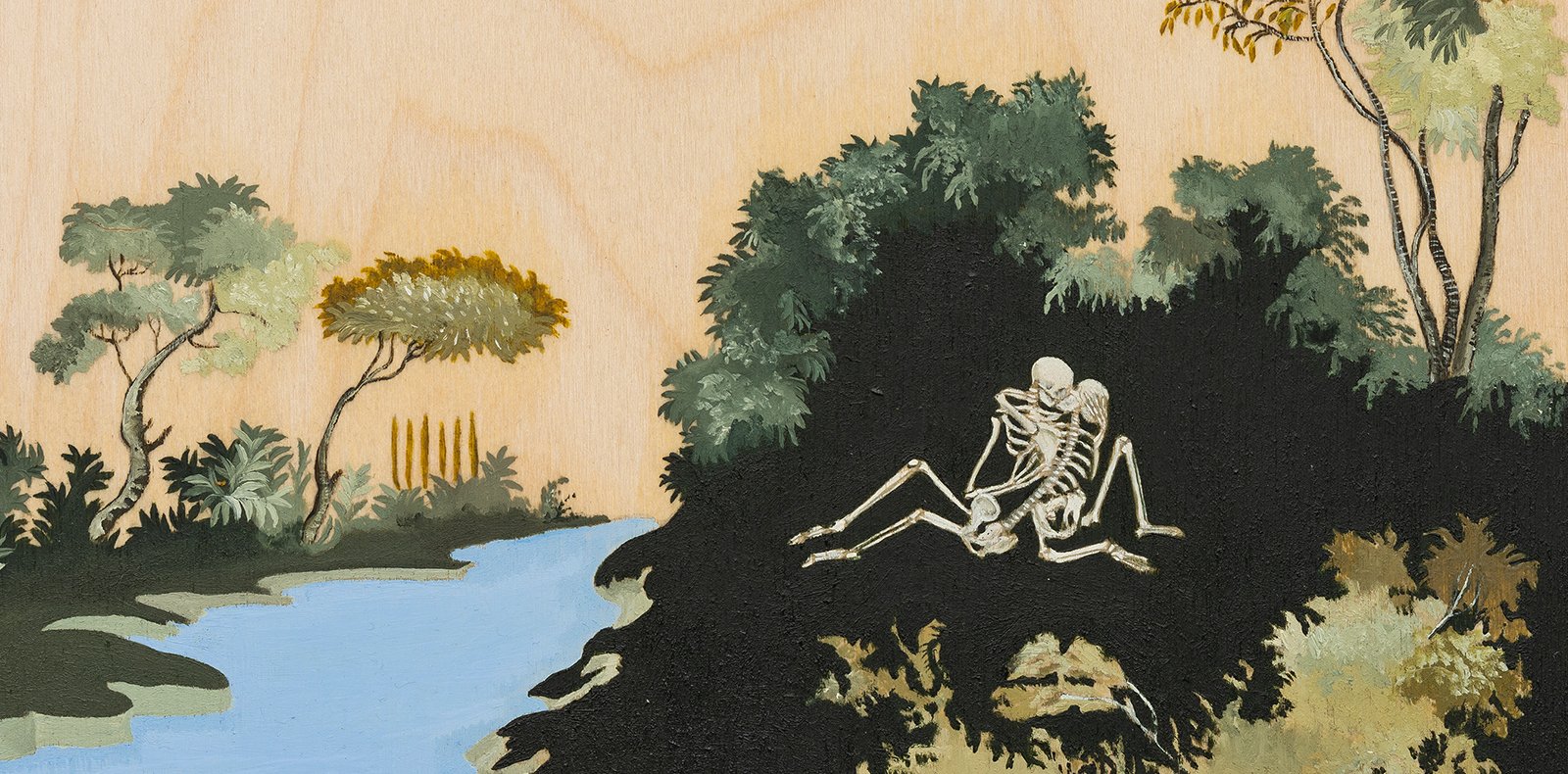

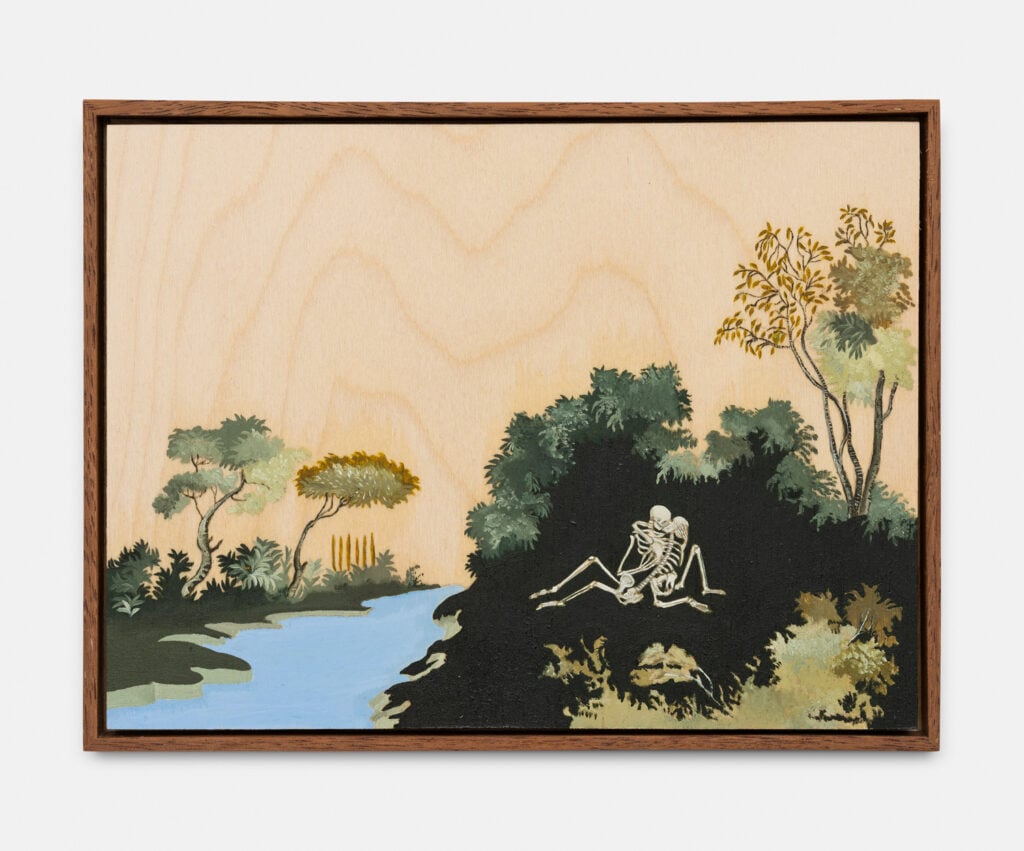

In 2023, Khatibi began painting in a manner where making the work also became a process for personal transformation. The series of pictures she painted that year – with titles such as I Would Give the Skin off My Bones and I Wanted Everything with You – explored what happens when the soul of a relationship dies, leaving only the skeletons of what was. Referencing artistic movements of the past, Khatibi reminds us that heartbreak and disillusion are universal experiences that connect us to all of humanity’s past, present, and future. She further allows us to see that humanity proliferates because we do not give up on the idea of finding love.

Himali Singh Soin, creator of the largest ikat ever woven

Also related to the universal and timeless experience of grief, Warlop’s practice emerged in the wake of her brother’s suicide, when she made art to understand how, overwhelmed with death and darkness, one can continue in this world. She connects with audiences through performances that push our ideas of what “liveness” can be. “Knock knock. Who’s there? It’s your grief from the past,” she says in One Song (2022). In this performance, 12 actors in sports uniforms warm up to the endless repetition of a song that one of them sings on repeat at different tempos while running on a treadmill for an hour until everything collapses, including the other performers and their fans in the bleachers who cheer them on to death. “Grief is like a liquid,,and it never goes away,” the song continues, but we can find meaning and moments of joy as grief shifts shape, turns sweet, and becomes a grape (in Warlop’s metaphors).

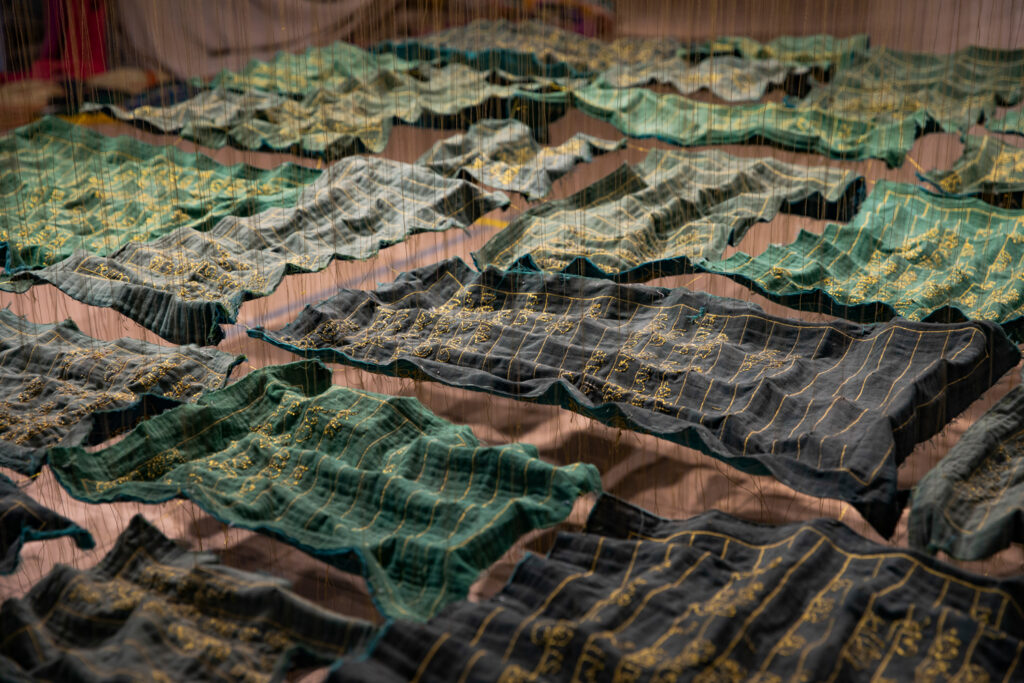

There are many forms of heartbreak beyond those of human-to-human bonds, like the heartbreak of planetary collapse, which is acutely felt around the world. Art can be part of a process that sensitizes us to these wider heartbreaks. In her poetic practice, Himali Singh Soin speaks from the perspective of resources such as salt and water to show how we are all connected. She and I are working on creating the world’s largest ikat fabric to tell the story of the erasure of the Aral Sea in Central Asia. Himali pointed out that some of the other drying seas in the region are also shaped like hearts.

Lauren Bon, The Smallest Sea with the Largest

Heart, view of the installation at Desert X 2023. Photo: Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X.

Heart, view of the installation at Desert X 2023. Photo: Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X.

Lauren Bon: a giant heart immersed in salt water

For DesertX 2023, the American artist Lauren Bon and I worked on The Smallest Sea with the Largest Heart, an installation inspired by California’s Salton Sea, another evaporating lake. A lace-like steel sculpture of a to-scale blue-whale heart was submerged in a pool pumped full of borrowed Salton Sea water. Rather than presaging death, the sculpture metabolized and created energy and clean water that was deposited back into the atmosphere, fueling the potential for future life across the run of the exhibition and visually transforming itself in the process.

Ashfika Rahman, winner of the Future Generation Art Prize

Environmental heartbreak is often related to societal heartbreak – for example, sexual violence in Bangladesh increases in areas with floods because it is harder for police to reach them. Behula These Days (2022–23) is a community healing project by the Bangladeshi artist Ashfika Rahman that reinterprets the mythological love story of Behula and Lakhindar through a feminist lens, highlighting the systemic violence against women in one of Bangladesh’s most flood-prone areas.

By tracing Behula’s journey, Rahman collected stories of women affected by gendered climate-based violence, challenging the cultural ideals of sacrifice and isolation imposed on them.

Fernanda Laguna: the heart as architecture

Also working on community projects and societal healing, the Argentine artist Fernanda Laguna uses hearts as characters in many of her artworks, highlighting themes of care, empathy, and solidarity in her efforts to uplift and support underrepresented groups. An artwork that still touches me since I first saw it at LACMA in 2017 is Laguna’s Plano de mi Corazon (para entenderme) (Map of my Heart (to Understand Myself), 2001), which presents the artist’s heart as an architectural floorplan, with various entry points and also an emergency exit. My heart swells when engaging with the topic of heartbreak, and I hope that after this three- year cycle of research, my collaborators and I will be stronger and better able to help others find the emergency exit to defeatist thought that holds us back from healing.

1st Bukhara Biennal: “Recipes for Broken Hearts”, organised by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, in September 2025 in Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh. In 2025.