15

15

At musée du Quai Branly, ayahuasca opens the doors to a new world

What does the world look like under the influence of ayahuasca? Until May 26th at the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, the exhibition “Shamanic Visions” explores both the effects of this hallucinogenic plant, which originated in an indigenous community in the Peruvian Amazon, and the ways in which its use has shaped artistic creation in that region and in Western countries. A captivating journey into the depths of the human soul.

By Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 15 December 2023. Updated on 20 June 2024.

In 1990, when asked by a journalist whether he would be able to create without using any substances, the writer William S. Burroughs spontaneously delivered an eloquent answer: “I don’t think so”. The American novelist’s work has greatly been nourished by experiments with alcohol, heroin, morphine and opium, to the point where these substances have become an integral part of his lifestyle and creative process. Among his various experiences, one moment marked a major turning point in his life – the first time he tried ayahuasca during his trip to South America. This beverage, made from vines of the indigenous Banisteriopsis plant, has the ability to induce a trance-like, mystical experience to its users. The latter experience hallucinatory visions and presences, while their sensory perception is transformed and increased tenfold. According to popular belief, this experience purifies the body. For centuries, this unique state of consciousness inviting dreams into reality has been at the heart of the collective and traditional rituals of the Shipibo-Conibo, an indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon, who use this preparation for ceremonial, spiritual, and therapeutic purposes. Their experiences with ayahuasca have given rise to a fascinating and enigmatic body of artistic work. The exhibition “Shamanic Visions” offers a fascinating insight into the topic until May 24th, 2024, at Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. It also helps bring about a better understanding of these unprecedented forms of spiritual elevation, which have gradually won over Western artists and writers in the age of globalization, and keeps being a source of inspiration today.

From ayahuasca to patterns drawn on textiles and ceramics

“The ayahuasca vine helps you connect with the invisible”, a Shipibo-Conibo woman explains in a video, as she prepares a pot to cook the plants that will eventually be ingested during collective rituals. While this first cooking usually causes nausea and vomiting, one has to wait for the second cooking to experience the eagerly-awaited visions. The invocation of visions is traditionally accompanied by shamanic chanting. Despite its ‘invisible’ nature, the world encountered during this mystical experience generates precise shapes in most minds – regular, thin, curved, or straight lines, forming crosses, squares, triangles, and other small circles which, when joined together, give birth to some kind of labyrinth… The Shipibo-Conibo have called these patterns ‘Kené’ and have even attributed several meanings to their drawings according to their own beliefs, before attempting to reproduce them themselves – one evokes the wings of birds, while the other represents the spirit of the eye.

Like other abstract and geometric motifs found in many different civilisations, from the Moucharabieh in Morocco to the Asanoha in Japan, Kené is also the bearer of an age-old history. Painted on textiles or ceramics, the techniques are passed down from one generation to the next, usually from mother to daughter, and are generally a guarantee of protection. The recent works by contemporary indigenous artists featured in the exhibition are proof that ayahuasca has given rise to a creative tradition based on an inner, personal experience, constantly opening the doors to new interpretations. In one of her embroideries on cotton fabric, Shipibo-Conibo artist Chonon Bensho has reinterpreted Botticelli’s Venus with characters from her community and a landscape decorated exclusively with Kené patterns.

Fascinating works of art celebrating the Amazon

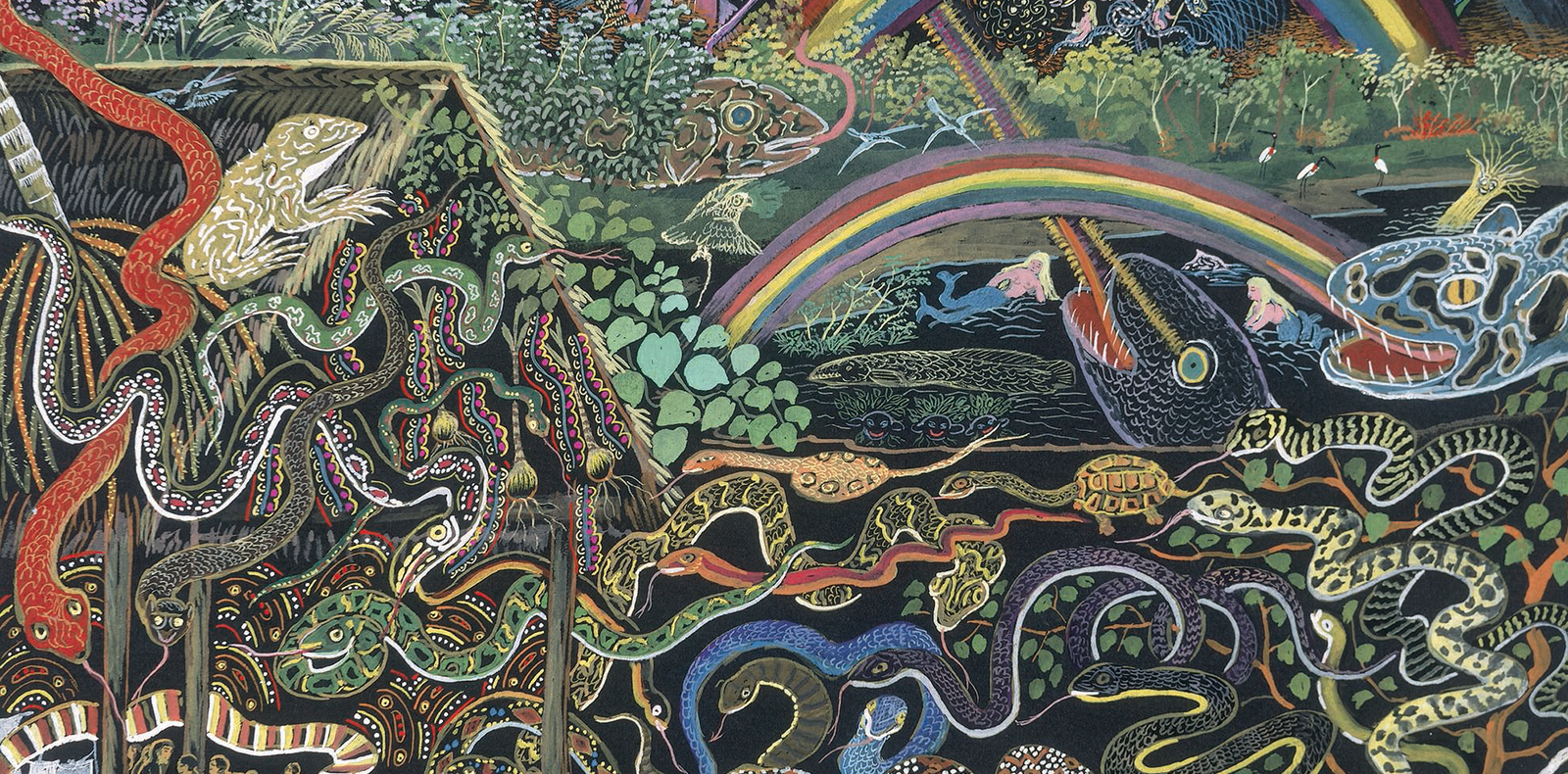

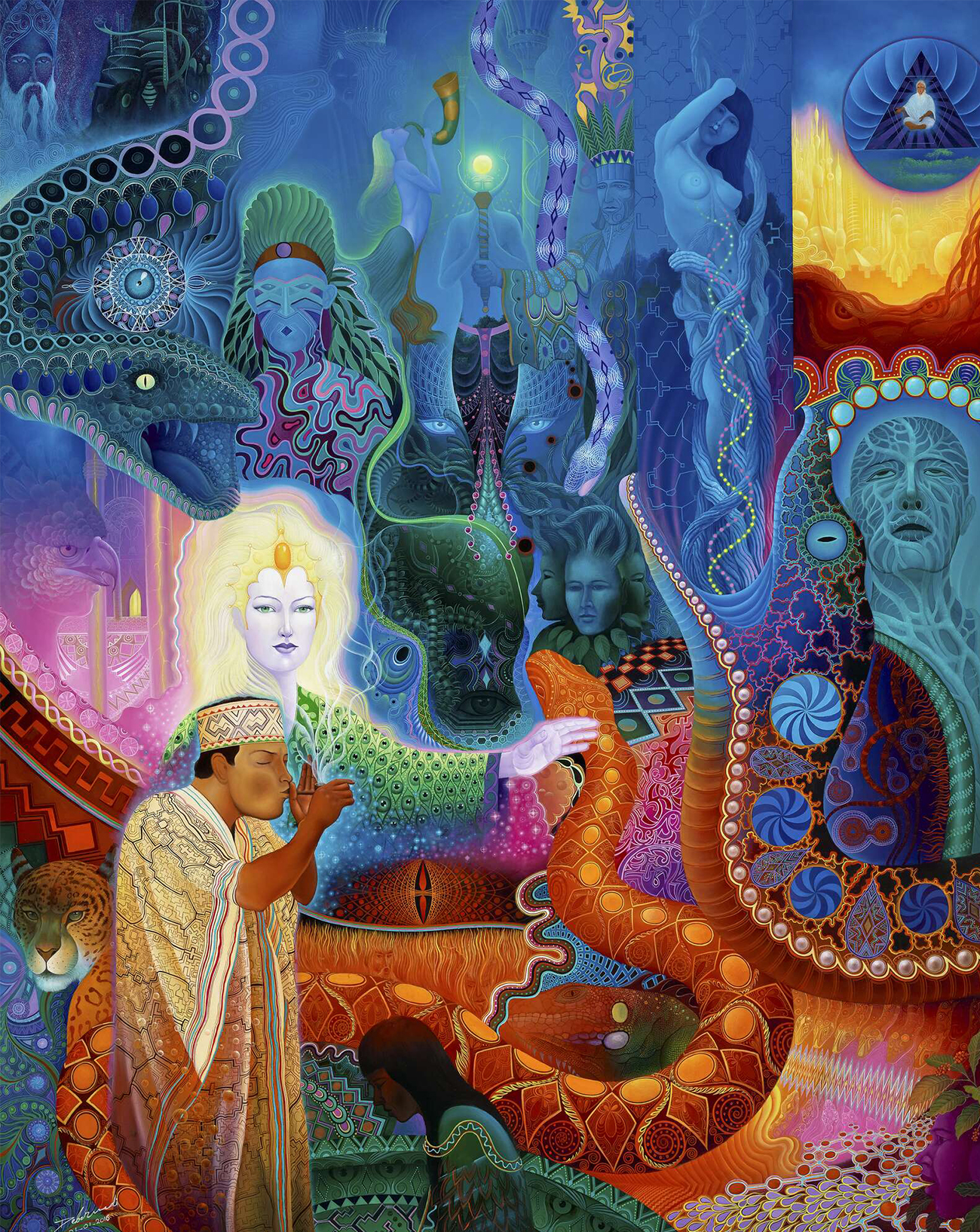

Presented above the museum’s pre-Hispanic and South American collections, the exhibition “Shamanic Visions” reminds us that the artistic angle, nourished by ethnographic and anthropological research into the Shipibo-Conibo community, prevails over a scientific approach that would attempt to study how ayahuasca works and the symptoms it induces. When exploring the exhibition, one is drawn into the dense, colorful paintings of Peruvian artist Pablo Amaringo, with their almost Boschian compositions filled with luxuriant vegetation and fantastic animals. One can also witness the astonishing divine creatures sculpted in wood, then covered in painted motifs, by José Tamani and Jheferson Saldaña, and try to decipher the symbols on the canvases of Roldan Pinedo, another member of the Peruvian community. While a number of recurring elements sheds light on the content of the visions, such as trees, birds and, very often, myriads of snakes, all these works seem to converge towards the same goal. Pablo Amaringo himself clearly expressed it in the 1990s: “to preserve and respect the nature around us”. It is hard not to read a reminder of the current critical situation of the Amazon rainforest, the ‘green lung’ of our planet.

Shamanic visions are spreading from the Amazon to Western countries

It was only a matter of time before these transcendent experiences found a resonance outside the Amazon. As the exhibition shows, the international diffusion of ayahuasca experiences reflects the history of the Western domination in the Americas, from the colonial exploitation of the Amazon in the 19th century to the development of “shamanic tourism” from the mid-20th century onwards. Writers were openly fascinated by these experiences. While the names of William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Aldous Huxley stand out in the exhibition, it is hard not to think of Charles Baudelaire’s 1860 collection Paradis Artificiels (Artificial Paradises), in which the poet already described both the creative benefits and dangers of hashish, or Henri Michaux’s Miserable Miracle (1956), a collection of texts and drawings produced by the artist under the influence of mescaline. All these Western authors have demonstrated in their own way that, while psychotropic and hallucinogenic substances can indeed open the door to another world and nourish the imagination, their qualities are quickly overtaken by the many dangers associated with their use, which is very different from the Shipibo-Conibos’s ancient healing and divination at the core of the community’s mythology and philosophy.

The Western perspective and conception of art is so distinct from that of the indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon that it will probably never be able to provide a true understanding of the Shipibo-Conibo creations born of ayahuasca. Beyond their undeniable artistic qualities, the artworks displayed in the exhibition barely succeed in accurately transcribing the experience. However, at the end of the exhibition, French filmmaker Jan Kounen sets out to meet this challenge through virtual reality, taking visitors on a fifteen-minute hallucinatory journey. The 360° journey through snake jaws, arachnid baths, cathedral-like rose windows, and other ossuaries is a praiseworthy attempt to have a better understanding of this occult world. Yet, the unisensory and inevitably individual experience of ayahuasca, here deprived of the direct connection to nature, smells, or human interactions, keeps us a long way from total immersion. And so much the better… in order to retain its exceptional power, ayahuasca cannot give up all its secrets so easily.

“Shamanic visions. Ayahuasca arts in the Peruvian Amazon”, from November 14th, 2023 to May 26th, 2024 at Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 7th arrondissement.

Translation by Emma Naroumbo Armaing.