6

6

Who is Yuko Hasegawa, a japanese art authority ?

2018 is a great year for japanese art in France, with a whole host of concerts, dance shows, theatrical events and exhibitions being planned. Top of the bill is hang at the Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild, the work of Yuko Hasegawa, the greatly respected chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

Interview by Emmanuelle De Montgazon,

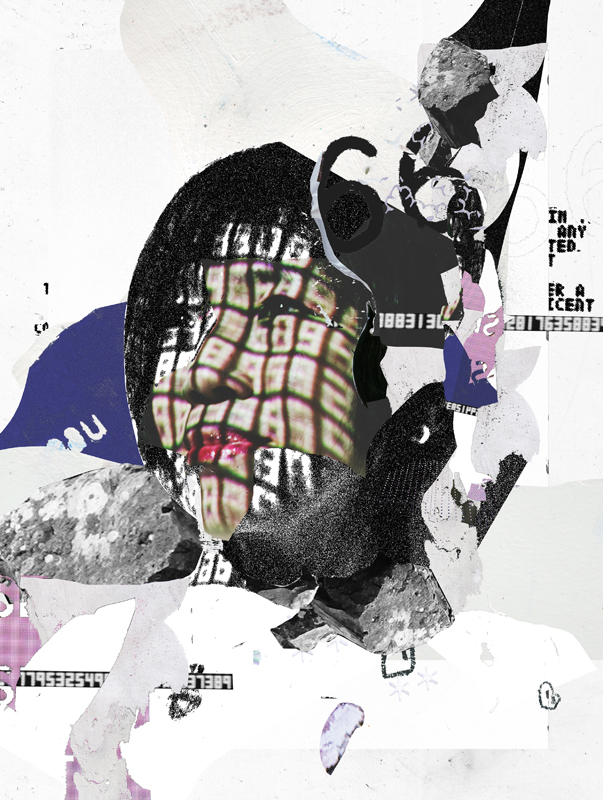

Portrait by Raphaël Vicenzi.

Numéro art: For 20 years you’ve been one of the most active Japanese curators on the international scene, addressing the changes taking place in the contemporary world from a unique perspective in shows such as De-Genderism [Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, 1997], Sensorium [MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, 2007] and New Sensorium [ZKM, Karlsruhe, 2016].

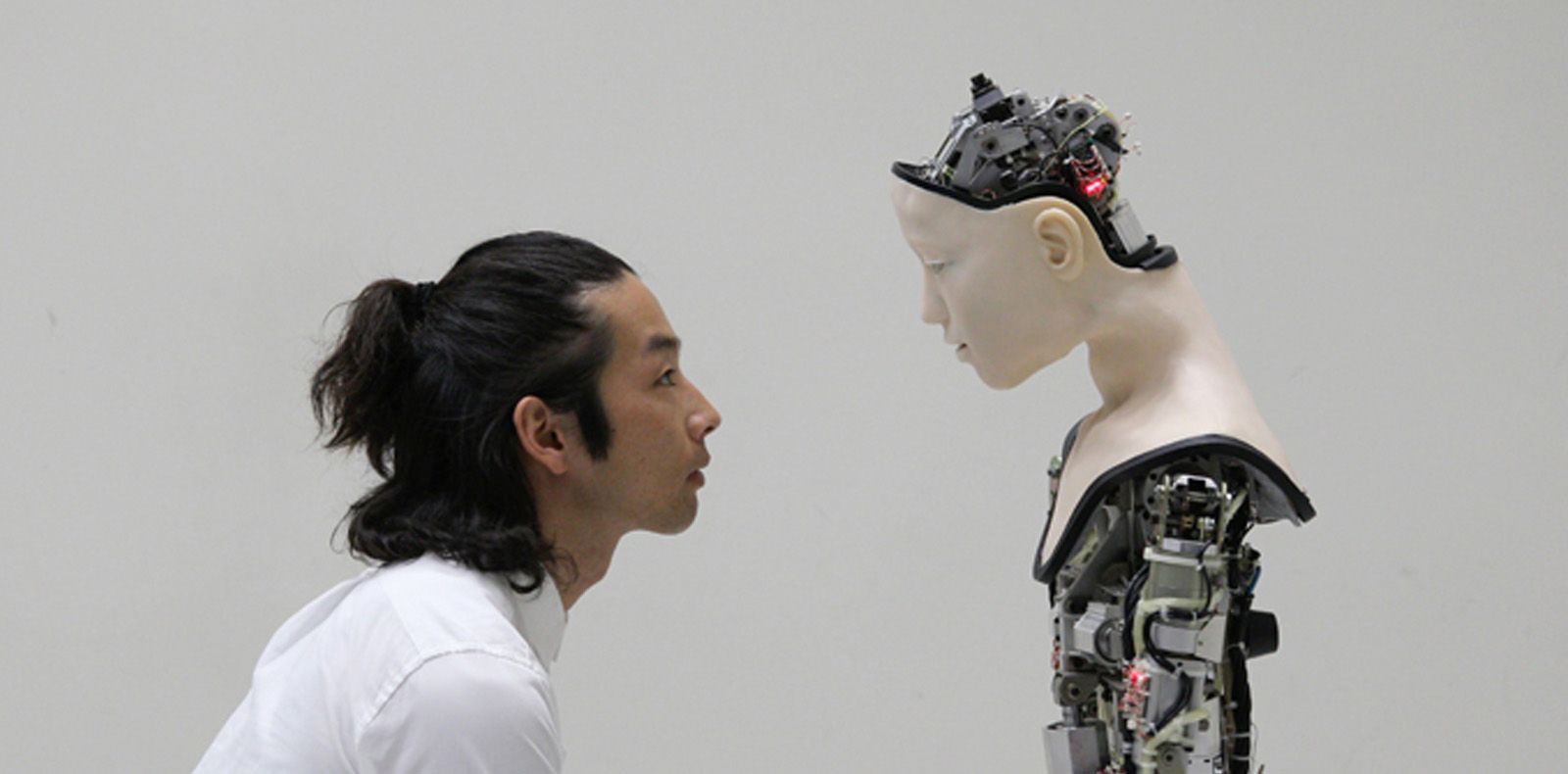

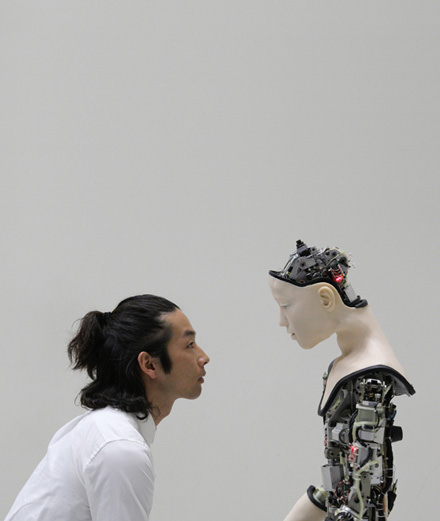

Yuko Hasegawa: I’m particularly sensitive to how we think about the body, and the way perception of it affects artistic practices. Our environment is constantly evolving, there have been radical changes in the media, and our bodies respond differently to these new parameters. They’re the transmission zone that allows us to still be connected to others and to handle change. That’s why I’m interested in all types of artistic practice, be it art (especially performance), fashion or design. I’m as interested in the physical body as in the “subjective” and “augmented” body because it’s an intrinsic part of our identity, which is a combination of our origins, our identification as a human being and the memories contained within us. The subjective body is an augmented body, so it’s a question of adjusting these corporeal memories to the multiple layers of our environment.

“The strange, the disturbing and the grotesque are important concepts found in many works, like those of Takashi Murakami or Yoshitomo Nara, references to the kawaii [cute] movement.”

Your interpretation of art in Japan is one that distances itself from Western influences.

Unlike the 1986 Centre Pompidou show Japon des avant-gardes 1910-1970, which aimed to highlight the link with Western culture and thought, I offer another perspective on this relationship. The concept of the avant-garde is a purely Western idea, and you could call my perspective post avant-garde to the extent that I highlight artists who developed their practices at a distance from Western influence. For example, the Mono-ha movement, which emerged in the late 1960s, is constantly compared to Arte Povera. The artists of Mono-ha obviously knew Arte Povera, but their thinking was original and their ideas totally different. Similarly, in the 1980s, the techno-pop group Yellow Magic Orchestra developed its aesthetics outside of the Western canons, combining an innovative electronic sound with influences from folk and ethnic music.

For the Japanorama show at the Center Pompidou-Metz, you and architect Kazuyo Sejima divided the space into six themes, like the islands of an archipelago.

The six islands acted as a constellation of concepts that came together and overlapped in a completely fluid way. Human nature is intrinsically connected to matter, both alive and inert. The “Strange Object/Post-Human Body” section was important in this sense as it touched on the fact that humans, in both body and mind and as “pliable subjects,” are connected to matter, nature and the animal – in short, to the whole of their environment. In art, for example, the various strands of the Pop movement stem from sources as different as animistic spiritual thought and subculture. “Pliable subjectivity” is linked to this multi-faceted environment. That’s why the Japanese are gifted when it comes to coexistence, collaboration and collective participation. Kazuyo Sejima’s space encouraged visitors to become “pliable subjects” as they crossed the islands, which weren’t really separate and, because of the transparency, could be seen from any location.

The show was somewhat ambivalent and troubling…

The strange, the disturbing and the grotesque are important concepts found in many works, like those of Takashi Murakami or Yoshitomo Nara, references to the kawaii [cute] movement. We also find them in Haruka Kojin’s “landscapes” and in the characters of Izumi Kato and Aya Nakano. They make us realize that it’s hard to rely on our perception, which constantly pushes us to discover new areas of sensibility.

And women artists?

All the great female artists, architects and fashion designers, such as Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Rei Kawakubo and Kazuyo Sejima, came from well-to-do backgrounds, which means they were aware of their freedom and could disobey. Toyo Ito said of Sejima that she was ahistoric and free of all influences. This can also be said of young artists like Sputniko!, Sayaka Shimada and Haruka Kojin. All three trust in their perception, which is what makes their work unique.

In post-war Japan, art was anti-establishment and political, with the Gutai movement and groups like High Red Center. Is this still the case?

In post-World War II Japan, the worlds of art and activism were very close. It was a period that permitted types of art that deliver a message. Artistic activism diminished greatly during the economic bubble of the late 80s and early 90s.

“In Japan, the individual does not oppose society, but you can escape Japan’s rigid and oppressive social code through new communities, which you might call “colonies” or “tribes,” that explore other ways of being.”

There’s no longer open opposition to society?

In Japan, the individual does not oppose society, but you can escape Japan’s rigid and oppressive social code through new communities, which you might call “colonies” or “tribes,” that explore other ways of being. Rather than being destroyed, society is disappearing with the arrival of alternative colonies; it’s a form of “soft power.” Artist Koki Tanaka does collaborative works and exchange platforms through which he creates a system of thinking that you might call “soft conceptualism.” In a very different genre, the Chim-Pom collective takes a much more journalistic approach to produce an art of action that is funny and exists in tension with politics. Its members are part of the post-Fukushima generation, which is coming back to activism through satire. And through clever use of social networks, they’re also building a larger community.

You’re curating a personal show about the collective Dumb Type at the Center Pompidou-Metz. How important is it in the Japanese art scene?

Dumb Type is like a huge tree whose branches just keep on growing. In the mid-1980s it developed its own protocols by radically rejecting conventional, dogmatic systems. Dumb Type doesn’t openly criticize society, but offers an alternative, poetic way of living together. Democratic and non-hierarchical, it produces art that is particularly open and free. By pushing the limits of art, Dumb Type artists broaden the scope of our perception and bring us to new cognitive levels. They’re the precursors of an emerging ecology of new media.

What does technology bring to artistic creation?

There’s no real antagonism between artifice and nature. Our relationship to technology and new media helps bring us back to our own “physicality.” I call this the “ecology of new media.” It’s linked with animist thought. I’ve been watching its development closely for many years. Some artists from younger generations are revisiting the relationship with the artificial, positing that material has its own autonomy or “life,” like Yuko Mohri with her installations. But this new ecology can also be immaterial – for instance collectives like Rhizomatiks use algorithms and internet flows in their work.

The West and Japan perceive time in a very different way.

In Japan, the free appreciation of space can also be found in a different perception of time, which corresponds to a centripetal mode of thought, as Augustin Berque calls it. This is very important: if time isn’t linear, as in Western thinking, it’s much easier to create all kinds of hybrids.

You’ve pointed out the complexity of these hybrids.

We must consider the concept of hybridization without duality or linearity. It’s pure experience, a rhizomatic existence in which contrary concepts coexist. Each “subject” has a multitude of answers and lives in a space of ambivalent coexistence. This joins up with what I call “organic soft didacticism.”

You also talk about physical intelligence.

Experiencing the world through the body is essential. Take the art of floral composition, the tea ceremony or traditional theatre: knowledge is transmitted through the body, and interpretation by the body takes on an intellectual dimension. Kazuko Okakura’s The Book of Tea can be considered a work of philosophy in that it allows us to address a variety of philosophical questions through corporeal practices.

Tell us about the show you’re preparing for Japonismes 2018 at Paris’s Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild.

It’s intended as a dialogue between creativity and innovation in Japan across the ages. I wanted to highlight thematic dualities, not by opposing them, but instead showing they can work side by side, or even become one and the same environment. A dress by designer Anrealage, for example, evokes the terracotta decorations of the Jomon prehistoric era; a painting by Anne Laure Sacriste echoes Shibata Zeshin’s traditional lacquer and silk work. In some ways we’re dealing with philosophical landscapes inspired by the animistic beliefs still popular in Japan, which transcend hybridization or synaesthesia. The show’s approach is aesthetic and philosophical, an alternative to Western dualism and human-oriented thinking. I want to emphasize the concept of “organic didacticism,” which is inspired by contemporary animism and which places the human and the non-human on the same level. It’s something that you also find in certain theories developed by European socioligists in the 1980s. We can’t change the world, but we can change the way we look at it. We must find a way of being in the world that doesn’t exclude others.

Exhibition “Fukami, une plongée dans l'esthétique japonaise”, until the 18th of August 2018 at Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild, Paris.