12

12

Who is Emma Reyes, the Colombian artist known for her lush canvases, recently rediscovered?

The life of this illiterate Columbian artist, born in 1919 and raised in a convent, is as novelistic as they come. At 18, she escaped the nuns, in her 30s began to paint, and ended her days in Périgueux, France, where a school now bears her name and where, in 1988, she painted a 14 meter-long fresco on the walls of the town library. Her fascinating life and work are at last being rediscovered.

By Éric Troncy.

An extravagant body of work that long remained unknown

“After a thousand things, I’ve finally arrived in Paris,” wrote the young Emma Reyes in 1947. Born in 1919, the Columbian painter and writer, who died in 2003 at the age of 84, had come to France after obtaining a grant from the Fondation Roncoroni to study at the Académie André-Lhote. During the voyage, she met the man who, 15 years later, would become her husband, the medical doctor Jean Perromat. Born in Bogotá to an unknown father, abandoned by her mother on a railway-station platform, and brought up in a Catholic convent from which she escaped on reaching her majority, the illiterate Reyes, who wasn’t yet 30, was obsessed with one idea: “I’m going to make pictures, the sort people hang on walls.”

Twenty years after her death, at a time when her name has been forgotten – or was never even familiar –, she has come back, it seems, to France. It is thus with a certain astonishment that one has discovered her extravagant and hitherto unknown oeuvre through a series of recent exhibitions.

Galerie Crèvecœur is presenting a remarkable exhibition of her work in Paris

Between October 2023 and January 2024, Geneva’s Musée d’Art moderne et contemporain (MAMCO) showed several of her canvases from the 1980s and early 90s, while as of March 2025, Bordeaux’s CAPC is showing a handful of paintings that constitute “a hang within the hang.”

This summer’s exhibition at the Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie du Périgord, Emma Reyes, une artiste haute en couleur, allowed the public to discover some of the 209 works she bequeathed to the museum, while one of her paintings featured in the main exhibition at last year’s Venice Art Biennale. This autumn, the Galerie Crèvecœur has dedicated an extraordinary exhibition to Reyes in its three Parisian spaces, the first solo show of her work since her death.

In other words, over the past couple of years various opportunities have arisen to see her output, a phenomenon that is in no way supernatural but is due to the passion of Reyes’s great niece by marriage, Stéphanie Cottin, who is president of the Emma Reyes Society, and to the commitment of two young French art dealers.

Emma Reyes: A childhood spent in a Colombian convent, dreaming of the outside world

After their mother abandoned them, Reyes and her sister Helena were placed, or rather locked away, in the Convent of María Auxiliadora just outside Bogotá. During her adolescence, embroidery constituted her principal occupation. For Emma Reyes, life outside the convent was an entirely abstract concept, since she never left the building and only heard about the wider world from new girls entering the institution.

“I spent my childhood in a convent without ever leaving,” she told the journalist Gloria Valencia de Castaño in 1976. “I lived in a world of dreams and abstraction, because we referred to everything that happened outside the convent as ‘the world,’ as though we lived on another planet. Naturally, this absence led our imaginations to become huge, crazy. We went so far as to imagine that the trees outside were a different colour, that people took other forms, and the anxiety about what lay out there in the world became so enormous that one day I decided to escape.”

The myth of Emma Reyes

Seizing her chance at the age of 18, Emma Reyes jumped into a train for Bogotá. “Everything was so unreal, because I’d never seen a train, or a tram, or even a car.” She recounted this escape, and her extraordinary, tragic childhood in the book Memoria por correspondencia (published in 2012, it topped Columbia’s best-seller list that year). Indeed so exceptional was her childhood that Columbian television broadcast a 14-episode series about it in 2021 titled Emma Reyes – La huella de la infancia(Emma Reyes – the Traces of Childhood).

Last century, it was normal to have doubts if an artist’s biography seemed to occupy more space than their work, and offered far more exciting narrative angles than the switch from figuration to abstraction or the sudden abandoning of colour… But in the 21st century, these stories have taken on greater importance. As the art correspondent to the French daily Les Échos, Judith Benhamou-Huet, wrote almost 20 years ago in her 2007 book Art Business, “In the art market as we know it today, an artist’s work can also be read through the prism of the myth that might be associated with it.”

In the case of Emma Reyes, the myth found an uninterrupted succession of occasions to express itself – reminding us perhaps that we sometimes expect artists’ lives to be so different from ours, so that all the fantasy of their existence, even when horribly cruel, will avenge us for the ordinariness of our own.

“I lived in a world of dreams and abstraction, because we referred to everything that happened outside the convent as ‘the world,’ as though we lived on another planet.” – Emma Reyes in 1976.

After leaving the convent, Emma Reyes lived in Paraguay, travelled all over Argentina before working for an architect’s office in Buenos Aires, moved to Washington, helped organize the first monographic Frida Kahlo exhibition, spent time in Mexico City, where she taught at the fine-arts school, moved to Rome in the 1950s, went out with Alberto Moravia, frequented the Roman intelligentsia, and finally moved to France in 1960…

There isn’t an instant in her life that is not propitious to the fabrication of the myth, including the current show at the Galerie Crèvecœur in Paris, a city where she first showed work in 1967, at the Galerie de Beaune. In her lifetime, she only had four exhibitions in French galleries, and no French dealers represented her long term.

A curious relationship between humanity and nature

The Galerie Claude Bernard showed her work in the 60s, but it also represented her friend Fernando Botero. Although he lent her his studio in the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, and had long discussions with her about the use of colour in her canvases, he refused to allow his gallery to represent any Colombian artists other than him. Alix Dionot-Morani and Axel Dibie, founders of the Galerie Crèvecœur, got the full measure of the Reyes myth when, after discovering her work two years ago, they went to Cali in Colombia to meet with a family that owns a large number of the artist’s paintings.

“From the start, we’ve been leading an investigation, and we discovered Reyes’s work in Cali, where this family owns canvases that date from 1953 to 2000. There’s a real variety, and for us the chance to see all the series she experimented with.” While exploring the archives, they came across other unexpected finds, such as a portrait of Emma Reyes by Paul Thek (1933–88) and the guest book from her 1967 rue de Beaune show, signed by figures such as the actor Jean Marais, the painters Henri Cueco and Fernando Botero, the author Edmonde Charles-Roux, and “Johnny Hallyday, yéyé singer,” as the French rock star described himself in it.

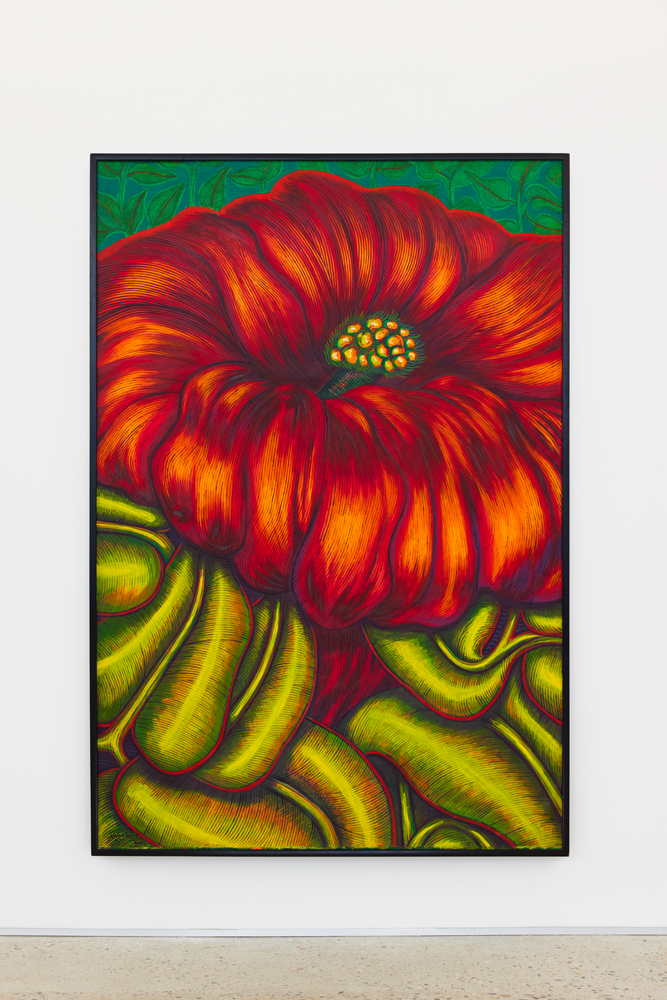

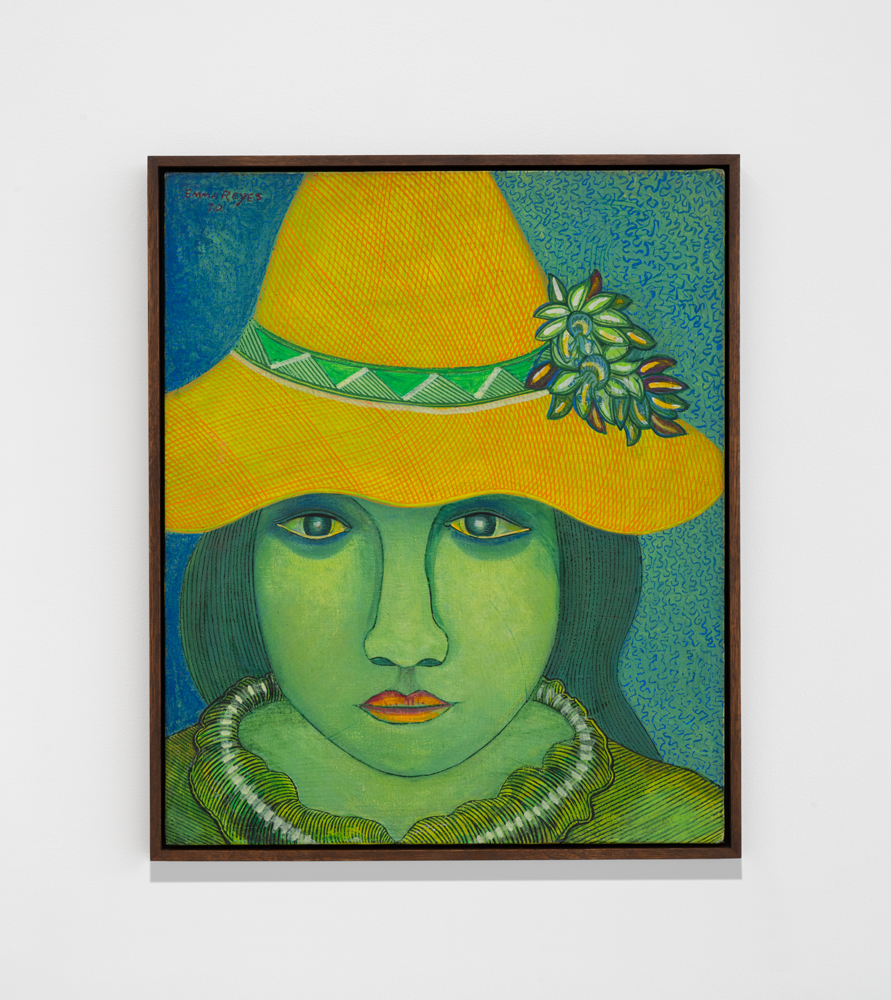

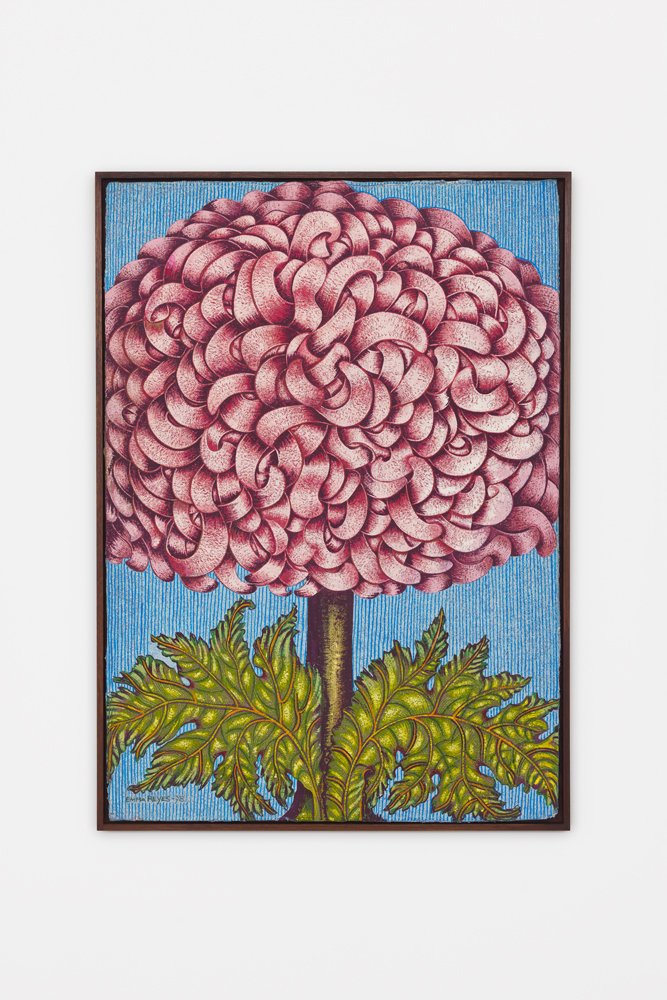

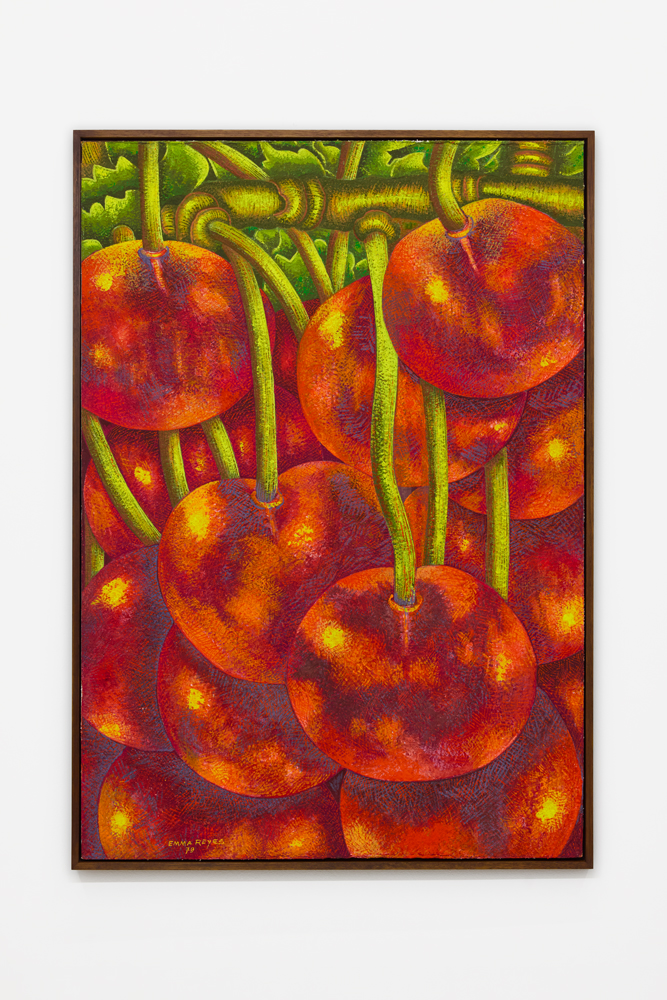

So much for the life – what about the work? We see it today in all the mysterious retrospective coherence of an idiosyncratic style that was rather hastily labelled “magic realism,” for want of a better term. Over a 50-year period, we find portraits and representations of plants, the former often mixed with the latter, creating a curious relationship between humanity and nature.

Close-ups and explosive colors

Her colours are explosive and expertly put together, and her way of framing her subjects in closeups that make them somehow bigger than the canvas recalls to a certain extent Georgia O’Keeffe, although her manner of painting is very much her own, characterized by volumes and shadows that emanate from the English text fine black lines that striate the surface.

While the influence of Colombian muralists can be felt as much of that of Cubism or Op Art, what one sees above all is the expression of a world that is hers alone, a world that is perhaps on the point of overwhelming us, like in the 14 meter-long fresco she painted in 1988 on the walls of the Périgueux Municipal Library, where giant flowers seem set to devour the readers – or to draw them into her imaginary world. If she ended up in Périgueux, it’s because her husband, Jean Perromat, had taken over his father’s surgery.

She had lost touch with him, then found him again; she didn’t agree to join him in the south, but stayed in Paris where she painted every day until 6.00 pm on the dot. But she promised she would go live him when he retired, which she did. A Périgueux primary school now bears her name, which is rather ironic given that she was never taught to read during her convent upbringing. Finally revealed to a wider audience, who is discovering it today, Reyes’s oeuvre is now out there in the world, and has found its own singular place, several decades after its creator’s death, in the history of art.

“Emma Reyes. Naturaleza muerta resucitando”, exhibition open until November 29th, 2025, at galerie Crèvecœur, 9 rue des Cascades, Paris 20th.