9

9

The success story of painter Nina Chanel Abney, exhibited at Perrotin

Nina Chanel Abney always dreamed of being famous. Less than twenty years after her debut, she has finally made it. Her paintings now sell for over a million dollars. In the 3rd arrondissement of Paris, the Perrotin Gallery is showing the first exhibition of this brilliant African American artist’s work until October 11th, 2025.

Nina Chanel Abney’s works are setting the Perrotin Gallery alight

“I always said I wanted to be a famous painter. I just never knew what that really meant,” she told Vanity Fair ten years ago. Since then, she’s had plenty of time to work it out, especially since the day in 2021 when one of her canvases went under the hammer at Christie’s for almost $1 million, three times the estimated figure. Back then, the market was not in today’s moribund state, tolling the bell for galleries one would have imagined better cushioned against bankruptcy.

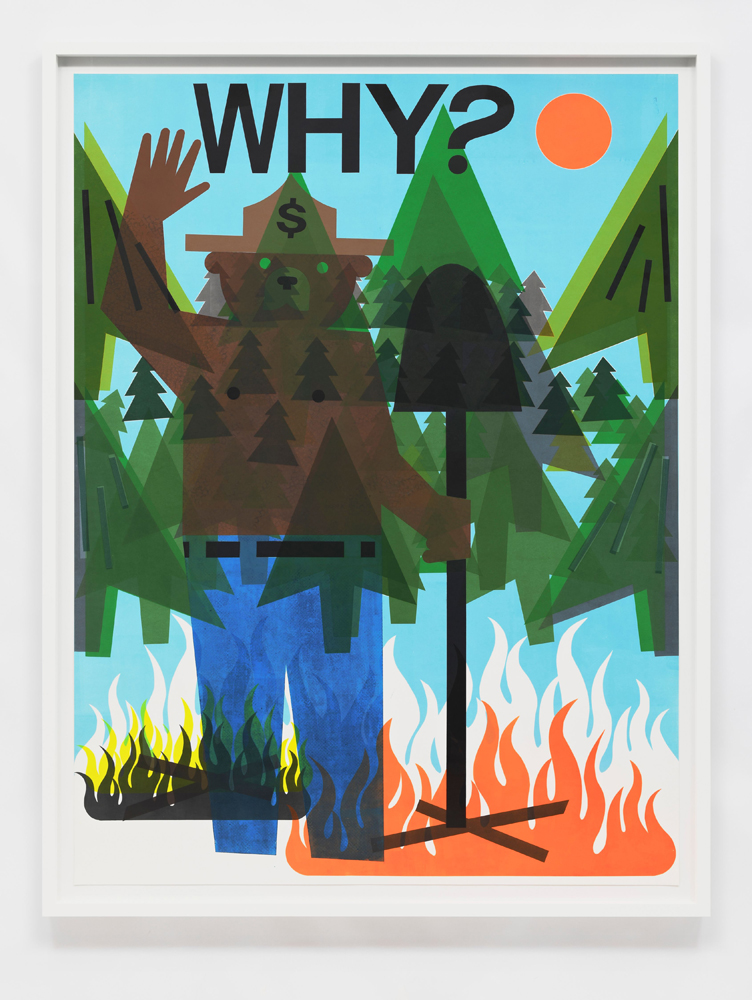

It must be said that these past few years Nina Chanel Abney has spared no pains, putting on shows and starting new projects at supersonic speed – a cadence that matches the incessant productivity of her working method. Until 11 October, at Perrotin in Paris (her first time with this particular gallery), she’s showing an exhibition full of fire, water, and catastrophes.

“I looked at the thesis show as my only chance to get the attention of a gallery.” – Nina Chanel Abney.

Now aged 43, Nina Chanel Abney was born in Harvey, Illinois. She attended several Montessori schools, studied in a liberal arts college (Augustana in Rock Island, Illinois), and then at Parsons in New York, the city where she still lives today.

As her time at Parsons came to a close, she was very conscious of what was at stake. “I looked at the thesis show as my only chance to get the attention of a gallery,” she recalls. “If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have known what to do. How else was I going to get someone to see my work? It was do or die for me at that thesis show because I absolutely did not want to have to go and apply for jobs. I knew I did not want to come all the way to New York and then have to do something I don’t want to do.”

The discovery of a promising artist

The day of her diploma, in 2007, she showed only one canvas, albeit a far bigger one than those she usually painted, titled Class of 2007. “I took everyone’s photograph and then I painted them as African Americans, and then I decided to paint myself white because, at the time, I was the only Black student in my class.” Curiously divided into a diptych, the work depicts its creator as a gun-toting blonde prison guard, while her classmates wear orange jail overalls.

“It was a standalone painting,” she explains. “It’s a two-year programme, and in the last few months you come up with something for the final show. I knew I had to create something pretty major because I was going to graduate and a lot of galleries come to your thesis show to look for artists to represent. I thought I was going to make a humungous painting.” Indeed, many gallerists attend these end-of-semester exhibitions to seek out new talent, and among those who showed up at Abney’s were Marc Wehby and his spouse and associate Susan Kravets, who were struck by Class of 2007.

Legend has it that Dirty Wash, Nina Chanel Abney’s first show at the Kravets Wehby Gallery in New York the following year, sold out in just a few days, including Class of 2007, which was bought by the celebrated American collectors Don and Mera Rubell.

Nina Chanel Abney’s unique creative approach

These days, one generally approaches an artist’s work by looking at the ideas they seek to express, but it seems to me that Abney’s oeuvre should be approached the “old-fashioned” way, via the most particular characteristic of the work, her technique. To make her images, she has invented special fabrication strategies that are so sophisticated and complex that no one else really understands them.

After applying layers of colour onto a magnetic plate, she

prints the paper on an engraving press between eight and 14 times, using between 14 and 20 colours. Extremely restrictive, this process, which allows a play on transparency that creates new hues, sets her oeuvre in a technical frame that is rather difficult to escape. Printed yet unique, her pictures feature bright, clear colours that are chosen to confound the viewer’s expectations.

A “colourfully seductive” body of works

She describes her work as “colourfully seductive” and “deceptively simple,” and the forms are indeed simple and distinct, as though cut out, which echoes her interest in collage, an absolutely fascinating technique that, curiously, seems to be out of favour with today’s generation. Her process, about which she gives away scant information, produces a very particular result in which colour has the leading role, with gratifying possibilities of invention. The minute an artist starts using flat primary colours and geometrical forms, it’s difficult to escape the shadow of Matisse; and the moment an artist paints the human body in abstract form, Cubism will come to mind…

These two references are regularly inflicted on Abney, but, without thinking too hard about it, one might also add Warhol, as her show Flagged at Chicago’s Anthony Gallery this year encouraged one to do. Whatever the truth, there is a consensus around the “familiarity” of her work, which is perfused with all sorts of references. Personally, she makes me think of Shirley Jaffe and, because of the letter U that appears in different iterations throughout her images, Wade Guyton.

Nina Chanel Abney’s political and abstract art

As for the subjects she tackles, clever is he or she who can find a link between them. From Black Lives Matter to questions of gender and ecology, they form a sort of catalogue of today’s preoccupations, or “contemporary cultural issues,” as they’re often obliquely referred to. “There’s so much information that comes at an individual during the course of a day,” says Abney. “In 24 hours, I may read the paper, get on the Internet and browse through YouTube, my Facebook timeline, look at Twitter, watch the news, watch Bravo, VH1, read gossip blogs, listen to music, and do all this while talking on the phone and texting, so it’s impossible for me not to cover a multitude of topics. I’m living in an age of information overload.”

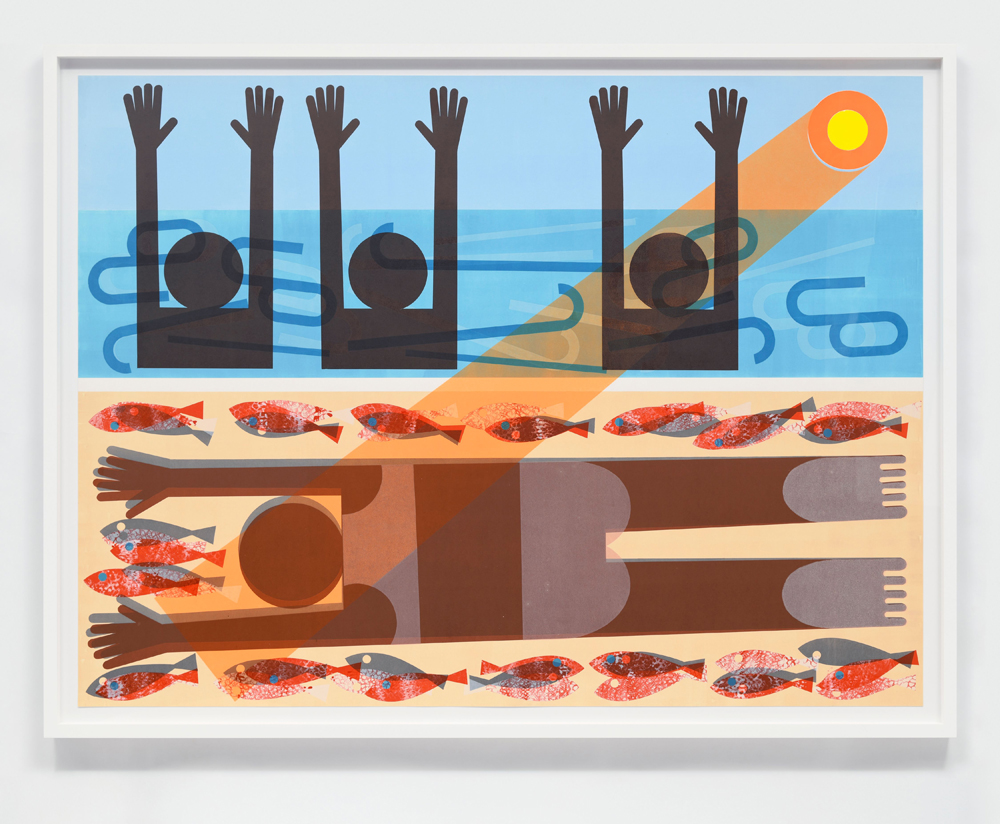

But the rather generic faces of her characters (a result of her technique) often prevent one from identifying their gender, and the great number of elements she includes result in compositions that encourage an open interpretation, with no precise message. “I’ve become more interested in mixing disjointed narratives and abstraction, and finding interesting ways to obscure any possible story that can be assumed when viewing my work,” she confirms. “So I don’t necessarily aim to send out a particular message. Rather, I want the work to provoke the viewer to come up with their own message, or answer some of their own questions surrounding the different subjects I touch on in my work.”

Social, environmental crisis and fashion collaborations

Her 2024 show Lie Doggo at New York’s Jack Shainman Gallery, or 2025’s Winging It at Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles, show the extraordinary health of an oeuvre that seems ready to go down any path as long as it lends itself to adventure. Some of her canvases are radically abstract, others display a palette that veers away from her usual predilections, and her large-format polyptychs are often mesmerizing, like the four-panel Breaking Bread (2024), her reinterpretation of The Last Supper, which shows characters in T-shirts marked “Brown family reunion.”

At Perrotin, the works tackle today’s social and ecological crises, and as such are firmly in the spirit of the times. Over the years she has also engaged in multiple “collaborations” with the likes of Nike, Crocs, and Tiffany & Co., while waiting to create her dream inflatable for Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Furthermore, she has authored memorable murals, such as the one she created at the Palais de Tokyo in 2019, or another that same year at the Musée d’Art contemporain during the 15th Biennale de Lyon, not to mention all the others she has done, in Chicago, Memphis, Portland, Detroit, Gwangju, Toronto, Boston, Cleveland, etc.

Her Perrotin show is full of fire, water, floods, and drought. What, one wonders, does it all add up to? For the particularity of her work is that the narrative is never complete. Are her figures in water drowning or enjoying a vacation? Are the fish around them dead or bursting with life? Abney’s work reminds us that there is nothing more disturbing than not knowing.

“Nina Chanel Abney. Now What ? Or What Else ?”, exhibition open until October 11th, 2025, at the Perrotin Gallery, Paris 3rd.