10

10

The exclusive interview with James Turrell, star of contemporary art exhibited in Paris

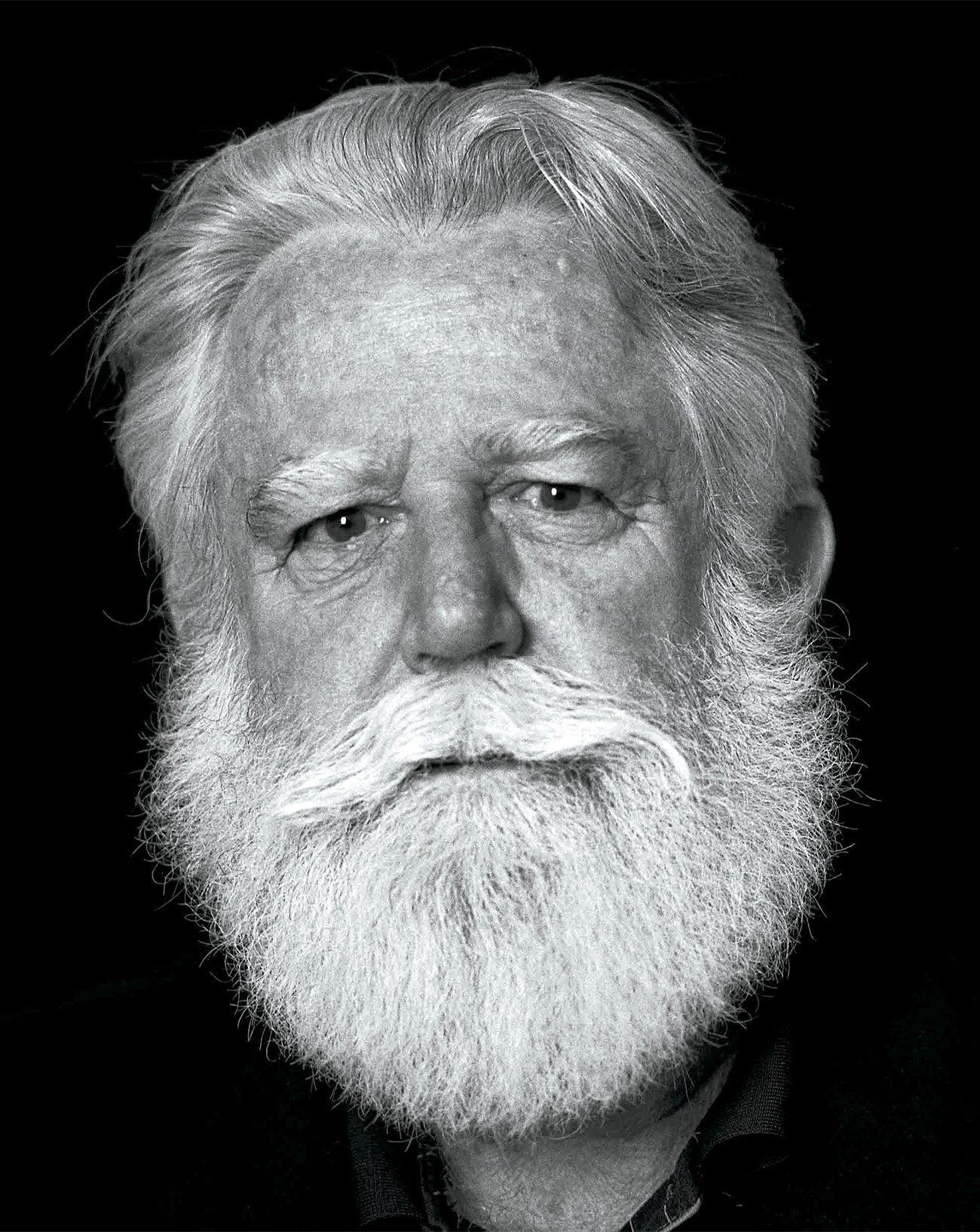

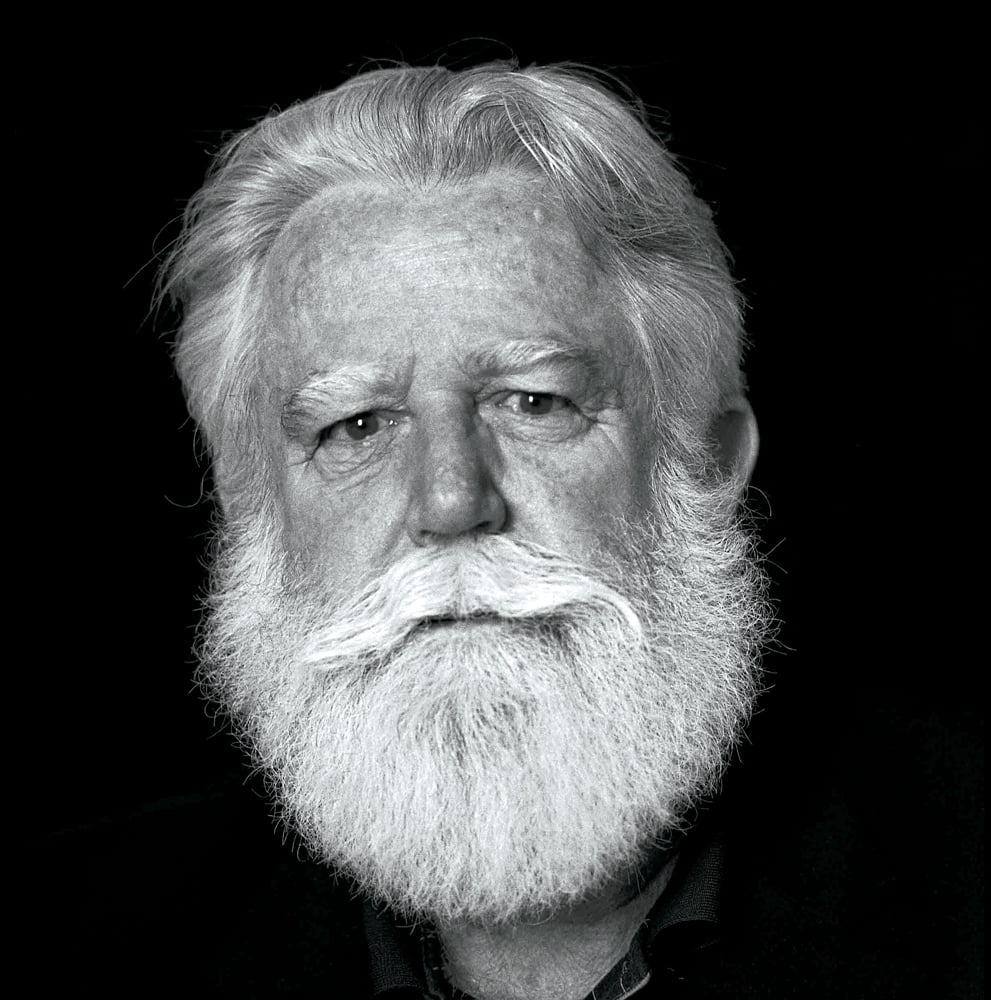

In the site-specific works of James Turrell, contemporary master of light, sky and earth merge to plunge visitors into a dizzying sensation of pure color and weightlessness. An adored artist, all the more so as he knows how to make himself rare, the American has been working for forty years on his life’s work, Roden Crater, an observatory nestled in a volcano he acquired. Until this monumental project is completed, the public will be able to rush to Gagosian in Le Bourget until summer 2025, to experience the intangible and fascinating art of the Californian.

Interview by Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 10 January 2025. Updated on 13 January 2025.

Interview with the artist James Turrell, exhibited at the Gagosian gallery in Le Bourget

In September 2022, artist Michael Heizer inaugurated his City in the heart of the Nevada desert. It took him over fifty-two years to create this gigantic ‘city’, made up of several colossal concrete sculptures. Long before him, Auguste Rodin worked on his famous Gates of Hell for over forty years. As for Europe’s largest public sculpture, made by Bernar Venet, its inauguration only dates back to 2019, even though the project began in the mid-1980s.

Despite the frantic pace of the art world and its constant demand for productivity, these examples are a reminder that artists have never ceased to put their heart and soul in long-term projects, without knowing for certain whether or not their artworks would be completed one day. These laborious quests can nonetheless give birth to true masterpieces, reminding us just how necessary risk-taking is to creation and history.

It has been forty years since James Turrell has been dedicating himself to the work of his life: a sky observatory nestled in a 300,000 year-old extinct volcano in northeastern Arizona. Property of the American artist since 1977, the Roden Crater and its surrounding site have been transformed as part of his ambitious project throughout the years. Luminous tunnels, galleries open to the sky and bathed in light…

The Crater Roden crater, the work of a life as mythical as it is mysterious

All in all, some twenty underground spaces are gradually weaving the architecture of this exceptional estate inspired by both the Mayan pyramids of Central America and the history of the Hopi, the Native American people who primarily lived in that region. While the site still remains closed to the public for now, it has already proven to be the apex of the work of the artist born in 1943. There, nature, architecture and light come together with the promise of creating a unique sensory experience, close to the total work of art so idealised by the Romantics.

“You know that one friend who’s been working on his thesis for ages, telling you that he’s about to finish it but in fact never does? For me, the Roden Crater is a bit like that”, the artist says, amused, before adding that the pandemic, inflation and rising production costs have considerably lengthened his deadlines. From his studio in Flagstaff, the closest town to the site, the now eighty-one-year-old American artist stands in front of a huge photograph of the volcano, as if a window had been opened to reveal this panoramic view, where a rainbow surprisingly seems to form a halo of light around it.

That incidental image is but an eloquent one to say the least. James Turrell is now considered as one of the ‘legends’ of contemporary art, not only thanks to this long-term project, but above all thanks to the creation of a radical and innovative body of work based on the immaterial, which has been spread all over the world for the past six decades. Also known as the ‘master of light’, the artist is presenting a new major solo exhibition this autumn at the Gagosian Gallery in Paris, which has entrusted him with the keys to its space at Le Bourget, just a stone’s throw from the airport. A rather fitting venue for an artist who is highly regarded in France, but whose public appearances are becoming increasingly rare.

Light, James Turrell’s favourite and exploration material

Born in Los Angeles, the American artist first came to public attention in the mid-1960s. One of his first works, Afrum Proto I (1966), consisted in the simple projection of a white light onto the angle formed by two partitions. The hexagonal shape drawn by the dazzling light gave the illusion of a cube emerging in relief from the wall. The foundations of Turrell’s work were laid – for him, an artwork comes to life through a skilful interplay between space, light and colour, which challenges the viewer’s perception thanks to the detailed study of physical phenomena. These principles quickly became the hallmarks of the new Light and Space artistic movement, whose emerging leading figures are James Turrell, alongside Larry Bell and Robert Irwin.

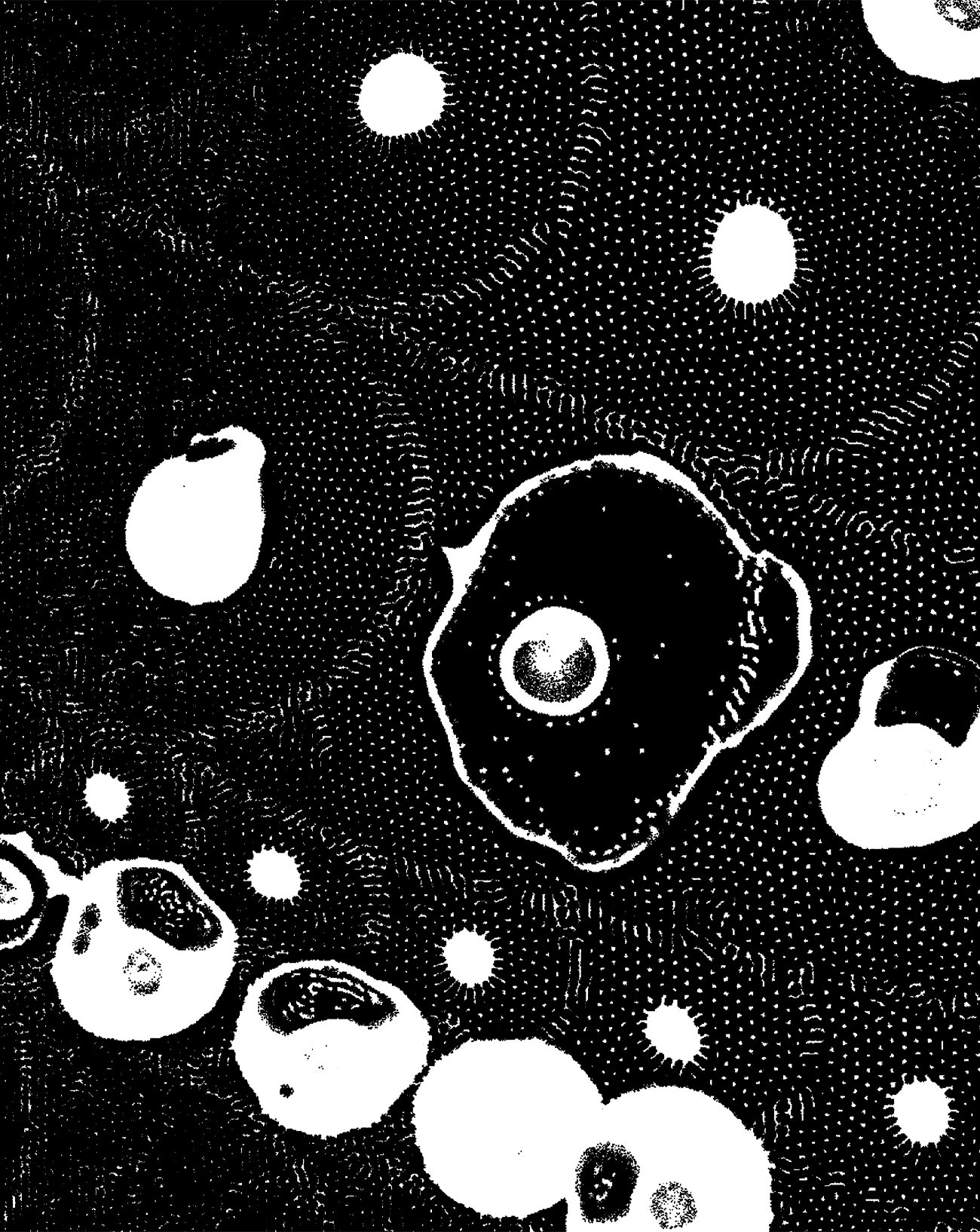

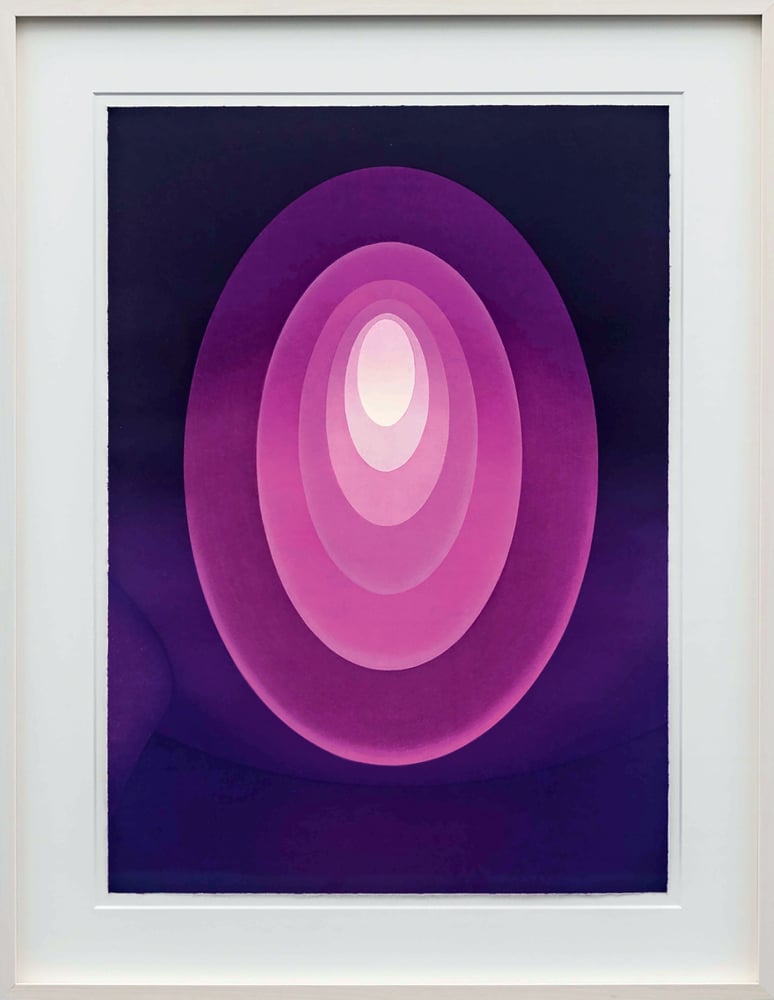

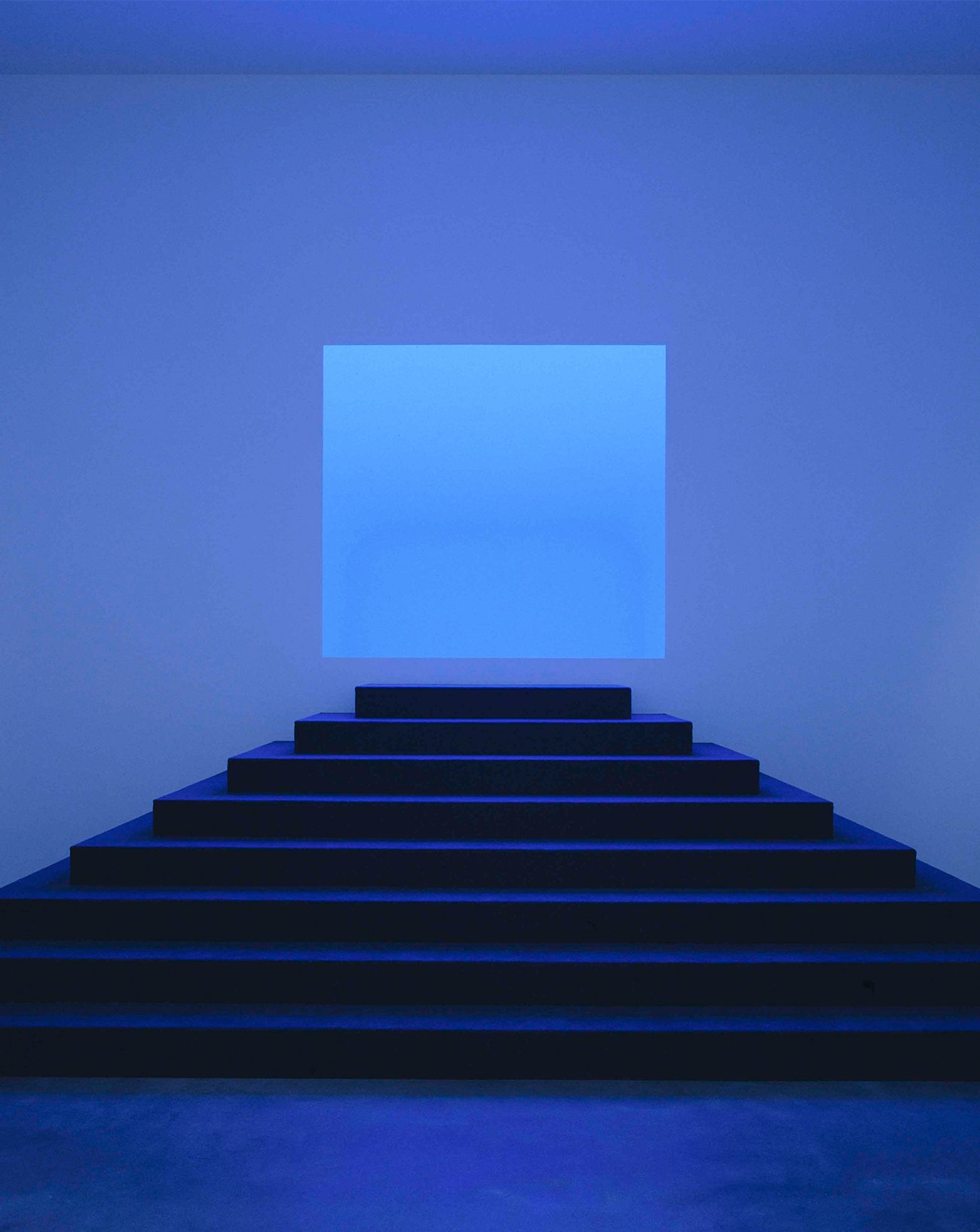

“My art has no object, no image and no focus”, he summed up a few years ago. His Ganzfeld, a series of works he started in 1974 based on the eponymous effect occurring when the exposure to a uniform, featureless field triggers a state of sensory deprivation, are a testament to that. Conceived on a human scale, Turrell’s installations immerse the viewer in a monochrome bath of red, pink, blue or green, in which saturated and unified colours are so intense that they engulf the viewer to the point of causing accidents. In 1980, a visitor broke her wrist as she leaned on what she thought was a wall and fell into one of Turrell’s installations. She claimed $250,000 from the Whitney Museum, which then claimed it back from Turrell, leading to years of litigation. In 2011, another woman destroyed an artwork after violently walking through a wall, thinking she was “jumping into a cloud” at the Venice Art Biennale.

“We’ve lost the habit of getting into paintings, and I want my pieces to revive that experience.”

James Turrell

Since he graduated in psychology of perception before completing his education at an art school, the Californian artist pays close attention to the audience’s behaviour when facing his works. “I’ve always been interested to see how everyone enters these new landscapes with no horizon, where there is no longer a top and a bottom, or a left and a right”. This loss of reference points is sometimes followed by an uncomfortable sensation of dizziness and vertigo, affecting those who might appear tough at first sight. “At one of my exhibitions in Russia, Vladimir Putin stayed in my installation for barely twenty seconds before pressing the button to get out!” Today, Turrell causes this effect at regular intervals to avoid completely disorienting the viewer.

Visitors at the Gagosian Gallery will be greeted by one of the artist’s last Ganzfeld. In this cornerless pavilion, with its blank, curved walls, an LED screen and coloured backlighting do all the work. Despite its structure, the artist considers this work to be much more pictorial than sculptural as it recreates the impression of a purely two-dimensional flatness in a three-dimensional space. “We’ve lost the habit of entering canvases, and I want my pieces to recreate that experience,” the artist explains as the aura of the work of art is essential to him. An aura that he can find in the paintings of Vermeer, Goya, Turner and the Impressionists, precisely because of their skillful mastery of light.

A universe nourished by his passion for the celestial world… and aviation

Despite the obvious spiritual dimension of his works very often experienced by the public, James Turrell has always spoken of light as a concrete, palpable entity. “I want to feel it, to sense its presence in space and the way it inhabits it,” he states. “We must not forget that we eat light; it’s food. Our balance is disturbed without it. We need it for melatonin, serotonin, vitamin D…”. While as a child the artist hoped to touch the light of dreams and bring it into the daylight, he now seems to use his work to build bridges between the realms of consciousness and the subconscious, and enrich our experience of the world in doing so. “We dream with many more colours than when our eyes are open. It’s no coincidence that those who have near-death experiences put a strong emphasis on light.”

These works are emblems of the Californian artist’s career and would probably not have seen the light of day without his all-consuming passion for aviation. As the son of an aeronautical engineer, the young man’s eyes were riveted to the sky as he dreamt of flying

from an early age. At the age of sixteen, he obtained his pilot’s licence and began flying. His most overwhelming sensory experiences all happened off the ground: “I remember once flying in the middle of tule fog, a thick ground fog specific to California. There was a stratus cloud above, and the sun was about to rise, which turned the sky red, then orange, and eventually yellow. Crossing this completely abstract landscape was gripping.”

James Turrell, an artist adored by critics and the public

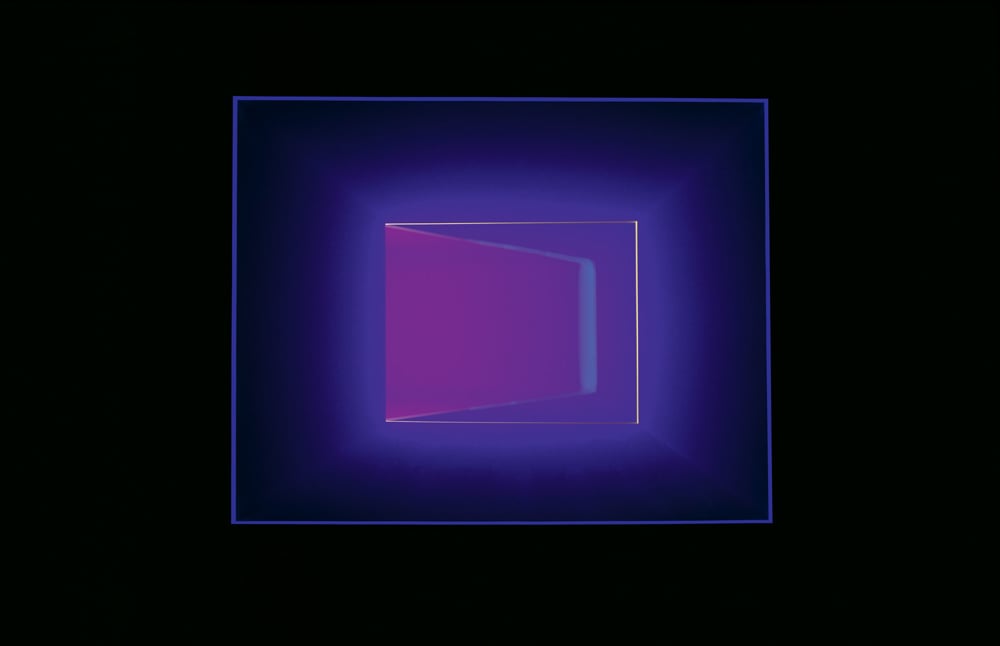

In 1969, that exceptional epic adventure inspired him to create the Wedgeworks series, a recent example of which can also be seen at the Gagosian Gallery. By projecting fluorescent coloured lights onto reflective surfaces in a room, Turrell creates an impression of depth that extends beyond the walls. “We pilots are often described as people and spouses who are difficult to live with since flying leads us to perceive things differently from others,” the artist comments. The latter is precisely working on giving the audience a glimpse of his highly singular paradigm. His passion for the celestial world has also inspired his most popular works to date, the Skyspaces, which are some kinds of outdoor capsules that can welcome a handful or dozens of people. Thanks to an opening to the sky on the roof and the combination of natural and artificial lights inside, the luckiest visitors can indulge in moments of intense contemplation.

While the first of its kind, built in 1974, is now part of the collection at Villa Panza in Varese, the Skyspaces have since sprung up all over the world, from Australia to Argentina and Norway. Today, eighty-five of them exist. Among the most impressive ones, the one located in Mexico City stands out for its oval shape, which looks like a moss-covered UFO, as well as the one installed at the University of Houston, whose pyramid-shaped structure topped by a large square roof offers ideal acoustics for live performances by the musicians on campus, in addition to the light experience. Nestled beneath the surface of the volcano and its cinder cone, Roden Crater contains several Skyspaces. In 2019, Kanye West unveiled some of them in his film Jesus is King (2019) shot on the natural site. The rapper, who sees James Turrell as one of his greatest inspirations, has also invested ten million dollars to help the artist complete his work.

“Like Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin, two of my art heroines, I found my source in the desert of the Southwest.”

James Turrell.

Over the last forty years, numerous plans, photographs, holograms and models of great aesthetic quality, considered to be artworks on their own, have followed the evolution of the project. Some of these objects are displayed in the exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery. Above all else, they unveil the artist’s love for the Arizona landscape, ever since he flew over it for seven months in 1974. “Like Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin, two of my art heroines, I found my source in the southwestern desert. (…) That’s why I try to go on walks every single day”. In addition to his daily walks in the desert, the artist still flies on a regular basis, even at eighty-one years old. “As long as my insurance allows it”, he adds, with a mischievous smile.

Today, James Turrell works with two architects daily, and visits the Roden Crater almost every day. His wife looks after the finances and investments, and helps him run the vast ranch on the site, whose profits help subsidise the project. Regarding the production of his works, a delegation of specialist contractors handles it, depending on the places where the artworks are to be shown – French manufacturers are working on the Gagosian exhibition for instance. It’s a well-oiled machine that enables the artist to remain as productive and visible internationally as ever, thus ensuring his longevity. Despite an exemplary career of sixty years and international recognition, the octogenarian has not managed to win over his family, who are very conservative Protestant Quakers.

James Turrell, isolated despite global recognition

“They don’t believe in what I do. According to them, art is vanity, an ego booster. Yet I’ve created several meeting houses [dedicated to Quaker meetings], as well as an installation in a newly renovated Lutheran chapel in Berlin… It wasn’t until I bought the ranch next to the volcano that they considered that I’d finally come to my senses. At last, I was going to make myself useful by farming and feeding my fellows!” From his French father, he says that he has inherited a special bond with France and its culture. In 1991, he was made Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by François Mitterrand and gained national recognition with his exhibition at Confort Moderne in Poitiers the following year.

To this day, James Turrell remains evasive regarding the opening date of the Roden Crater to the public, originally scheduled for 2024, and is still keeping up the myth to pique his fan’s curiosity. One question remains: how do you manage to stay on course for so long, without getting discouraged by such laborious work and the difficulties associated with it? “Basically, we don’t change, we just reveal ourselves gradually,” the artist replies, implicitly reminding us how much the journey takes precedence over the destination. “As time goes on, we learn more and more about ourselves.” A quite Socratic philosophy that also echoes the thinking of one of his greatest literary role models, writer and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “The earth teaches us more about ourselves than all the books in the world, because it is resistant to us. Self-discovery comes when man measures himself against an obstacle.”

James Turrell. The exhibition “At One” will be open from October 14th to summer 2025 at the Gagosian Gallery, Le Bourget, Paris.

Traduction Emma Naroumbo Armaing.