6

6

Striptease, activism and contemporary art, interview with Cecilia Bengolea

Born in Argentina, but living in Paris since 2001, this highly original visual artist has shaped her practice around dance. As well as being recognized for her collaborations with other artists, such as Jeremy Deller, François Chaignaud or Dominique Gonzalez- Foerster, she has made a name for herself with her “living sculptures.” For Numéro, she explains what gets her moving and grooving.

Interview by Nicolas Trembley.

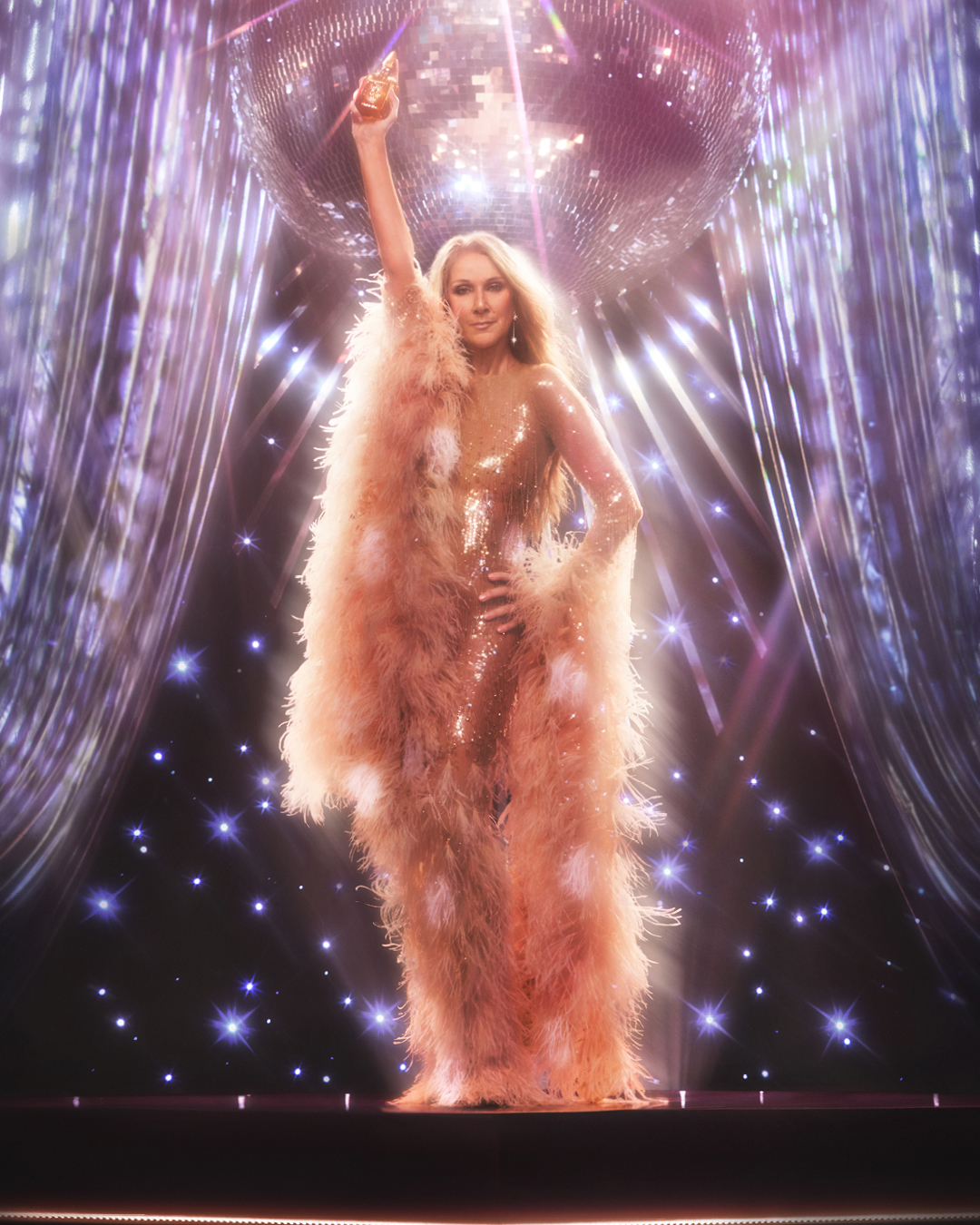

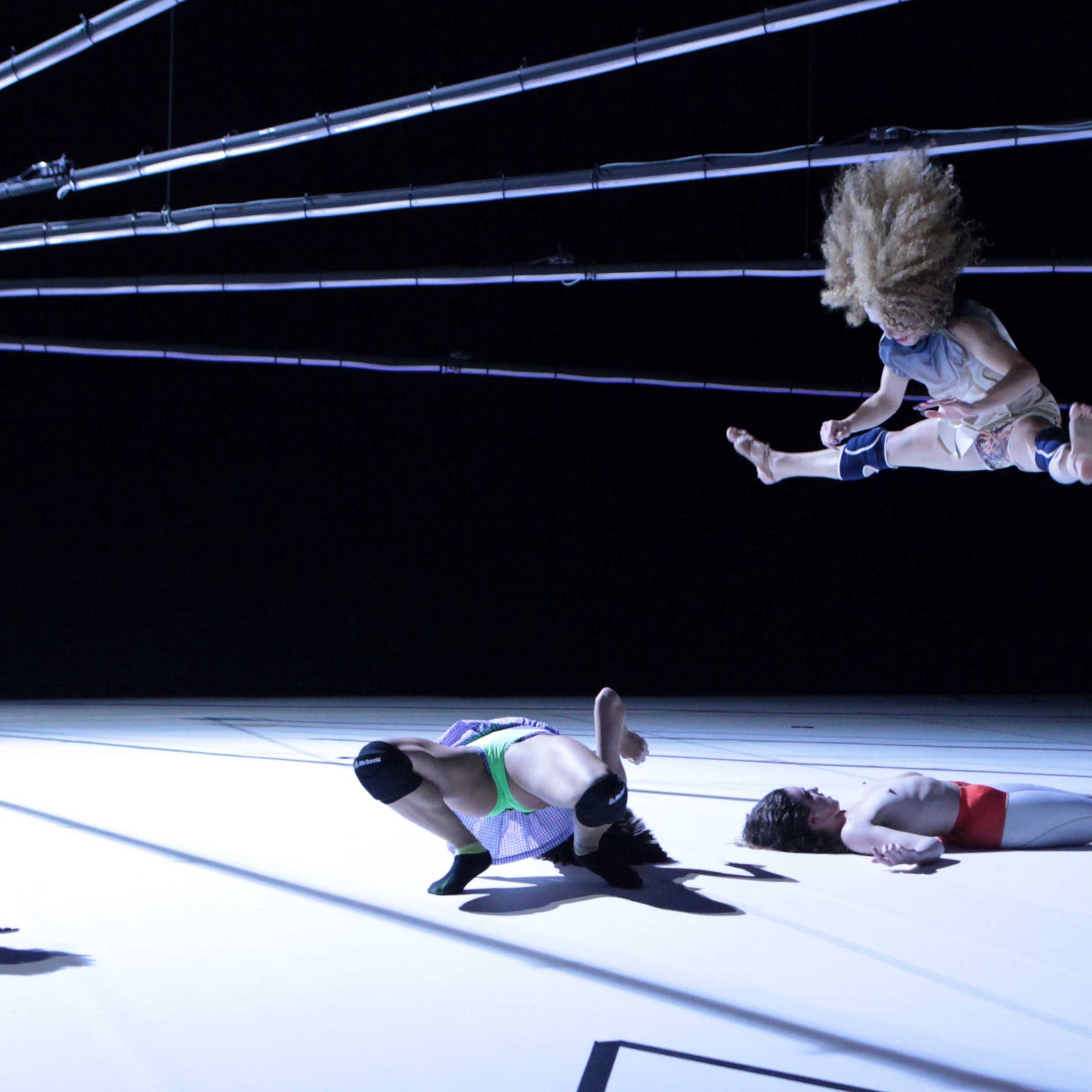

Cecilia Bengolea was born in Argentina in 1979 but has lived in Paris since 2001. Before graduating in philosophy and art history in Buenos Aires, she studied under Eugenio Barba, founder of the International School of Theatre Anthropology in Denmark. In France, Bengolea honed her contemporary-dance-based practice with Mathilde Monnier, but always with a basis in an ethnological approach to street dance. Ragga, hip-hop, dancehall – Bengolea does them all, to every kind of music, and sometimes even puts on ballet points for classical dance. As well as founding, with François Chaignaud, a dance company with a difficult-to-pronounce name – Vlovajob Pru –, she continues to collaborate with con- temporary artists. At the 2015 Biennale de Lyon and the 2016 São Paulo Biennial, she showed videos that she made with Jeremy Deller, while more recently she has taken part in performances by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. This relationship with fine art is natural for her, since she sees dance as an animated sculpture – often humorously, as was the case, for example, with Same Same Joy, her piece inspired by Thai boxing that was shown in early 2017 at the Elevation 1049 exhibition in Gstaad. For this extraordinary performance, she danced to techno beats in a fluorescent catsuit against a colourful video backdrop projected onto a ski slope.

Numéro: How did you come to make an artistic career out of dance?

Cecilia Bengolea: In Argentina, film, theatre and literature are very popular disciplines, but not so much dance. At 18 I went on a self-discovery trip to the north of the country where I met indigenous tribes who organized rituals to help me understand what I wanted to do – rituals involving fire, snakes, mushrooms and tree branches.

Do you consider yourself an artist, a choreographer, a dancer or a per- formance artist?

Dance is a means of expression within a structure – choreography. I like to have choreographic ideas, but also to let dance speak freely, without choreography. A performance is about sharing an experience. In my videos, I can show dance from a different angle to in a gallery or a performance. If I chose dance it’s because it seemed to me the most immediate medium with which one can communicate.

“At the time, I was stripping on the Champs-Élysées, not only to pay my bills, but also because I was conducting research into erotic dance and the social conscience of sexual objects.”

Which artists have influenced you?

Dancers from Jamaica – Dancing Rebel, Black Eagles, Oshane Overload Skankaz, Dhq Nickeisha – Michael Clark (especially in the film Hail the New Puritan), the book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, but also Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster for the conversations I had with her, and not forgetting George Condo, particularly through his jokes and his anecdotes about Keith Haring.

“It seemed to us that prostitutes and dancers had a lot in common, such as working with their bodily fluids, pleasure, pain, the idea of limits…”

How did your “animated sculptures” appear in your work, and what do they represent?

Lots of children have ideas about animism, and as a child I felt that stones held knowledge about the world. In 2009, I created a work with François Chaignaud in which there were several bodies vacuum-packed in latex bags. In the piece, our bodies became fetish objects, and I was suddenly conscious of being an animated sculpture. Moreover, when I started my performances in Paris, in 2004, I was doing striptease, and the fact of changing every evening into an erotic object was a huge pleasure. This ability to be two people at once gave me a special power: I was an object, and at the same time a subject who was master of her encounters.

You founded a company with François Chaignaud called Vlovajob Pru. What does the name mean?

It doesn’t mean anything. But perhaps “vlova” sounds a bit like “vulva,” “job” makes you think of work, and “pru” could be a humorous version of “pro.” François and I met in 2004, in Pigalle, at a demonstration by sex workers who were fighting for their social rights. At the time, François was writing a book about the history of feminism, while I was stripping on the Champs-Élysées, not only to pay my bills, but also because I was conducting research into erotic dance and the social conscience of sexual objects. It seemed to us that prostitutes and dancers had a lot in common, such as working with their bodily fluids, pleasure, pain, the idea of limits…

You recently presented a video piece at Dia Beacon and Dia Chelsea in New York. How impor- tant is video in your practice? François and I were in residence at Dia Beacon for two years, and in May 2017 we showed a series of performances which were filmed over a period of three weeks in the Dia basement with the work Fence by Dan Flavin. While performance is all about the here and now, photo and video interest me for their “archival” aspect. When you’re dancing in the street in Jamaica, you can’t transpose the specific context to a gallery or a theatre. In video and photography, the relationship between bodies and their environment is an integral part of the work.

Is there anything in particular that you’d like to get across through your work?

I’d like to make people want to dance, because the way a person dances reveals their personality. It’s a discipline that connects you directly to your emotions, and which can open us towards others, facilitating empathy.