27

27

Kohei Yoshiyuki and the voyeurs of Tokyo’s parks

By photographing the voyeurs who’d come to spy on couples having sex in Tokyo’s parks, photographer Kōhei Yoshiyuki confronts the viewer with his own impulses. Frightening clichés for some, a chronicle of a miserable Japan for others, the nocturnal coitus of his series The Park traps us and in turn, makes us voyeurs…

By Alexis Thibault.

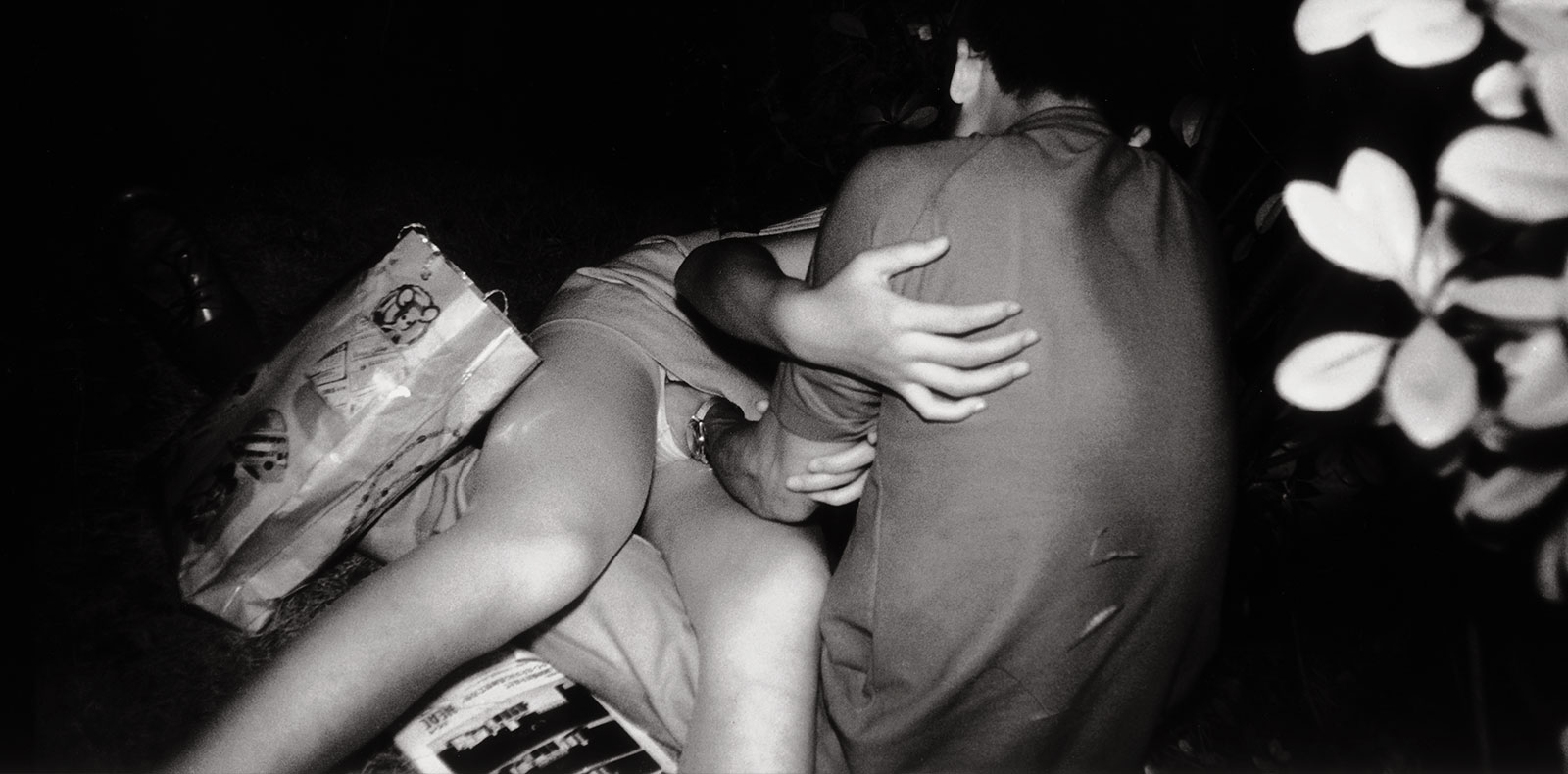

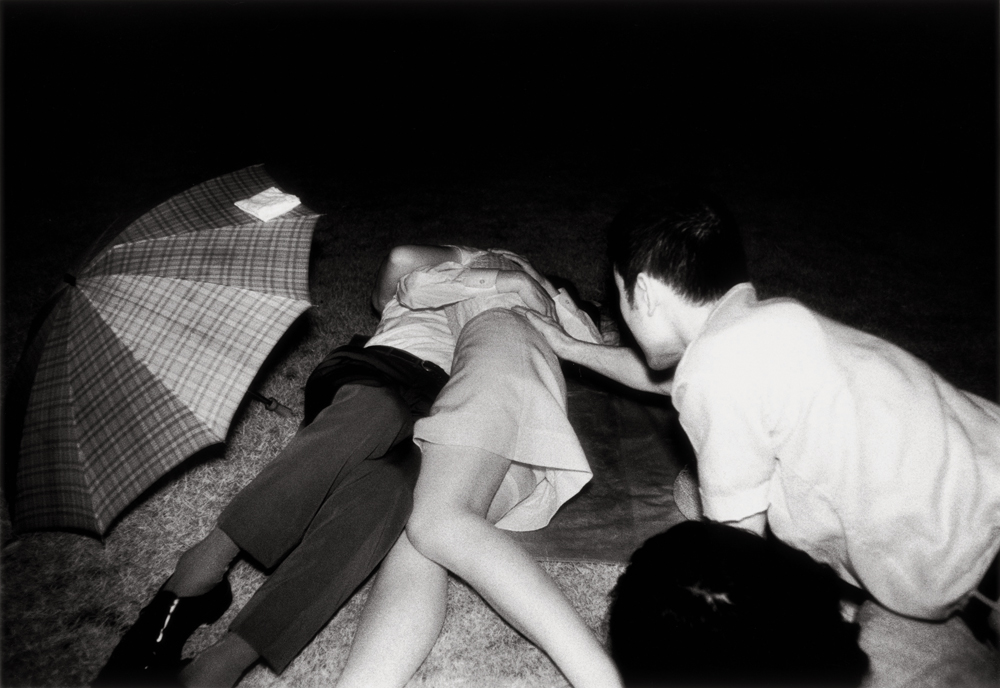

1. Lovers in Tokyo park

An umbrella hid the couple who had come to embrace in the imperial garden of Shinjuku, one of Tokyo’s most important parks… While the lovers tenderly curl up in each other’s arms, our gaze lingers on the young woman’s bare legs stretching out on the lawn. But other bodies also invite themselves to the party. Men crouching down and watching, illicit spectators of nocturnal coitus. These experts in voyeurism, were caught on film by Kōhei Yoshiyuki, a Japanese photographer in his twenties at the time. In the seventies, he infiltrated a community of libertines – of all sexual orientations – who made love in the capital’s parks, sheltered by bushes and dark nights, spied by onlookers who sometimes joined them in their quest for ecstasy on the grass. “At the time, Shinjuku Park was the ideal place for young couples to pass through after a romantic evening,” the photographer confided to journalist Dorian Chotard for Fisheye in 2015. “Seeing other couples in action like them seemed to excite them and I don’t think they had heard of peeping toms…” Scary shots for some, a chronicle of a miserable Japan for others, this photographic series entitled The Park was done with a 35mm lens, infrared film and a flash. It particularly fascinated the British photographer Martin Parr, who summarised it as follows: “The Park captures the loneliness, sadness and despair that accompanies human and sexual relationships in the great, rough metropolis that is Tokyo…“

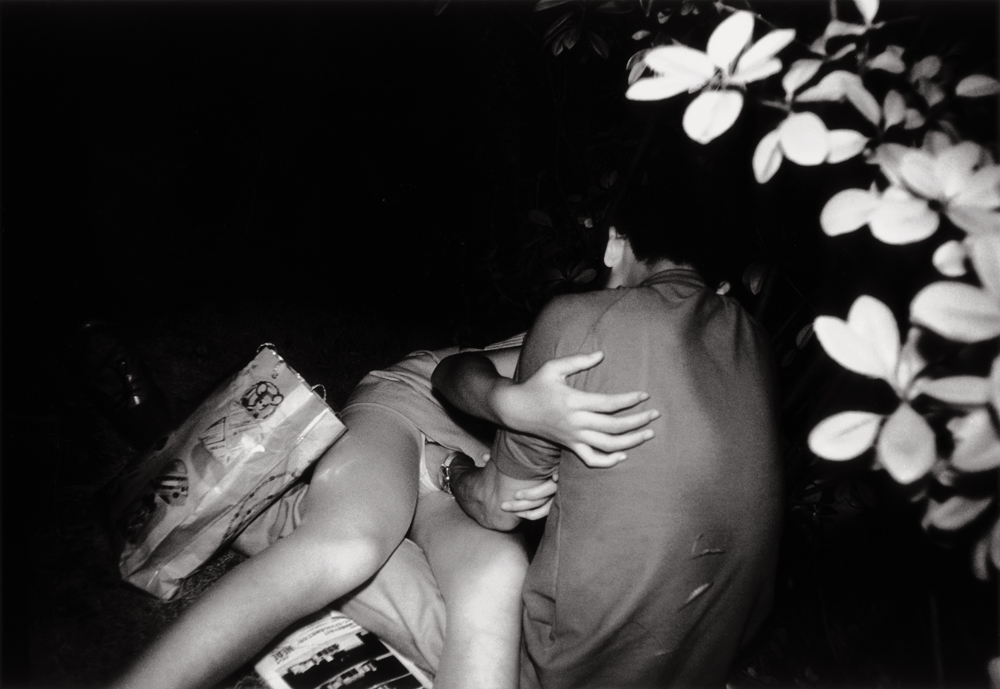

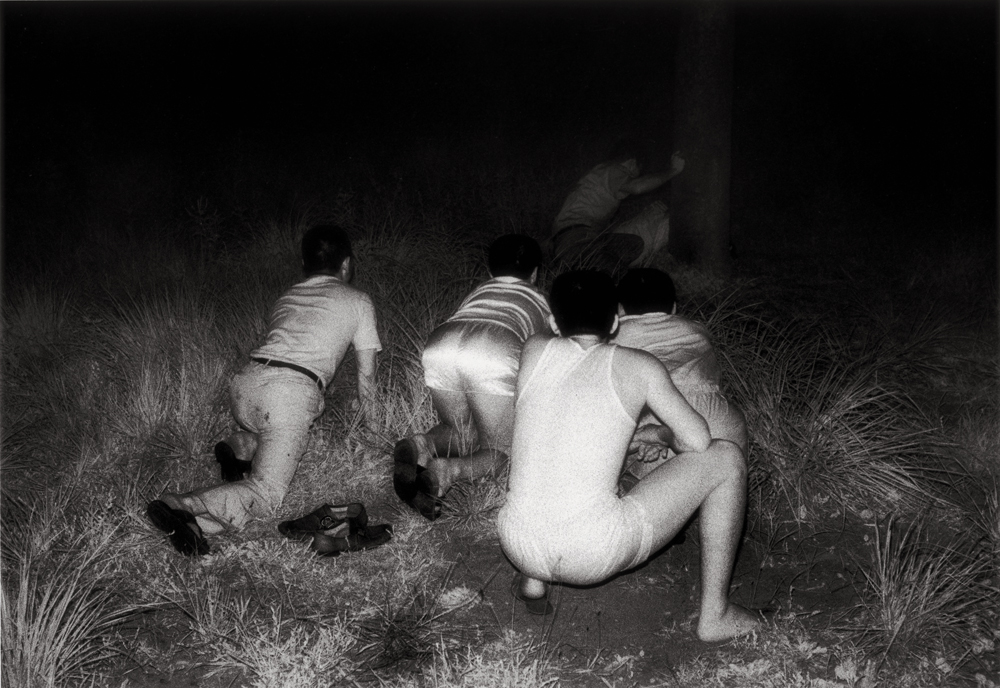

“The voyeurs would slowly approach behind the man and pretend to be him as they touched the woman. Often she didn’t realize anything… and neither did the man.”

2. Censorship and role reversal

When Kohei Yoshiyuki exhibited the results of his walks through the parks of Shinjuku, Yoyogi and Aoyama in 1979, he imagined a device as disturbing as the subject of his work: in the basement of the art gallery, a dark place without any windows, he arranged huge prints that each visitor, entirely immersed in the dark, had to illuminate with a torch… Visitors saw silhouettes hard at it in the night and men crawling, like soldiers, in the thickets to get an eyeful. “The voyeurs would come up slowly behind the man and pretend to be him when they touched the woman. She often didn’t realise anything… and neither did the man.” Kohei Yoshiyuki’s work shocks as much as it fascinates. And most of his black and white images were censored for almost three decades. Yet the photographer insists: “Voyeurism is an integral part of the photographic act.”

At its exhibition Exposed [2010], the Tate Modern presents 250 photographs taken surreptitiously or without the explicit consent of the subjects.

3. What cannot be seen…

According to the Larousse definition, voyeurism designates a (harmless) disorder of sexuality in which pleasure is derived by the covert vision of erotic scenes. By popularisation, it extends to everything that is likely to excite scopophilia, the pleasure of possessing the other through the gaze according to Sigmund Freud’s theory. A skilful combination of thrilling entertainment, macabre curiosity and the overcoming of one’s own shame, voyeurism immediately replaces the imaginary. As Jacques Lacan wrote: “What we look at is what cannot be seen.” In the age of social networks, camgirls, globalised surveillance and the dismantling of intimacy, it seems that human beings take as much pleasure in looking as in being looked at… or in looking at themselves. A haven for photographers.

In 2010, at its exhibition Exposed – Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera, the Tate Modern in London presented 250 photographs taken surreptitiously or without the explicit consent of the subjects. The show included images from the 1930s by Walker Evans, taken in the New York underground with small hidden cameras. But also photographs of nudes or lovemaking – including Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency – which put the photographer, like the visitor, in the position of voyeur. Voyeur par excellence, the photographer pushes us into voyeurism. And some, like Kōhei Yoshiyuki, even play with this trick by immortalizing the voyeurs in turn. Others, like Elliott Erwitt, attempt to artificially attenuate their own curiosity with the help of windows and mirrors. Does passing through the reflection, i.e. through distance, generate greater modesty? Windows can also be found in the controversial series by the American Merry Alpern, Dirty Windows [1995]. This photographer spent six months sitting in the dark, dressed in black, behind her camera on a tripod, scrutinising complete strangers like James Stewart in Hitchcock’s Rear Window. When she commented on her photographic series in the press, she unknowingly summed up this whole strange mise en abyme: “As the project went on, a feeling of paranoia set in: was anyone watching me?”