20

20

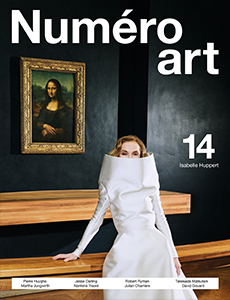

How Manon Wertenbroek’s sculptures enhance human body’s biggest taboos

For each issue, Numéro art showcases the French artistic scene most promising young talents. Today, focus on Manon Wertenbroek’s visceral sculptures, whose very delicate savoir-faire meets with organic and trivial inspirations, from sloughed skin to the bowels.

Portraits by Lee Wei Swee,

Styling by Samuel François,

Text by Matthieu Jacquet.

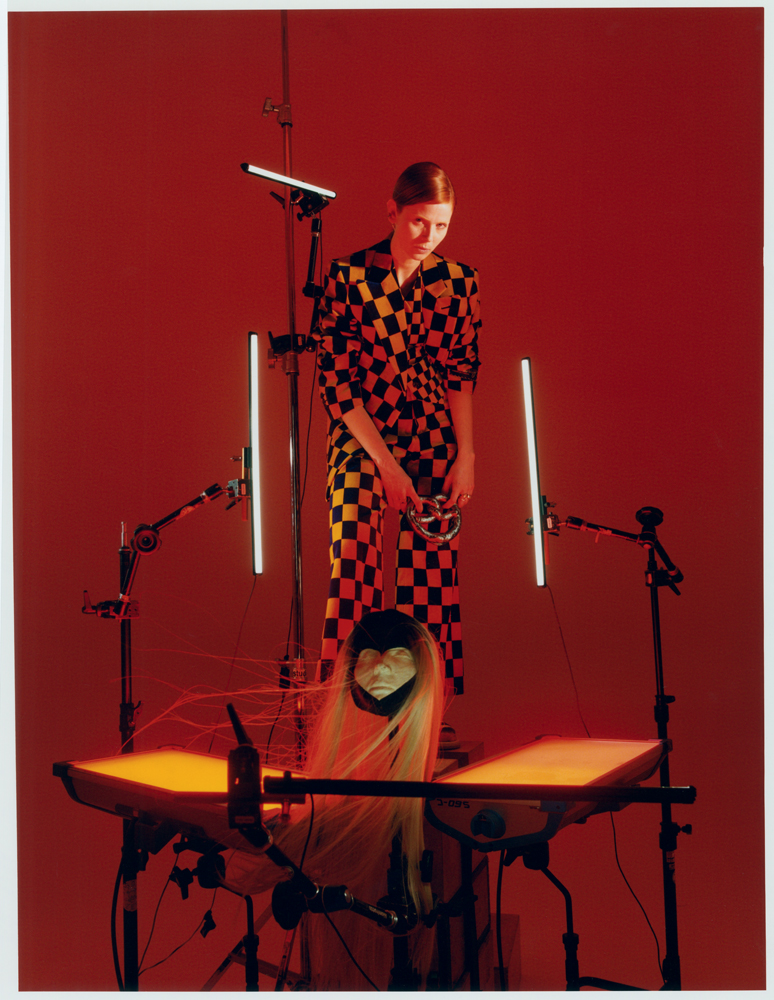

In 1974, French psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu formulated the concept of “moi-peau” [skin-ego], in which the palpable surface of the skin that covers the inside of our bodies reflects the surface of the more abstract “me” enveloping our psychic apparatus. Any attack on the skin is thus an attack on the self and the precious contents within. Half a century later, artist Manon Wertenbroek, born in French-speaking Switzerland to Dutch parents, seems unconsciously to have given the concept form, systematically materializing the skin without a body. With a vertical zipper glued to the wall and melted into its surface, the epidermis becomes that of the virgin wall hidden underneath the fastener; in window-like square frames, black and red leather evokes skin, stretched or creased by metal staples, bringing out its suppleness; with a jumpsuit on a hanger, the epidermis takes the form of flesh-colored latex, moulded to the artist’s form as though sloughed off like a snakeskin, and pierced with silver chains forming diamond-shapes like a Harlequin costume.

In her work, Wertenbroek speaks constantly of the body without ever representing it directly. She first tried her hand at photography, already fusing together objects, human beings and the environment at the fleeting moment she pressed the shutter. Her decision, just a year and a half ago, to work only as a sculptor was a revelation: she could finally base her approach on tactile contact with the material, evoking delicacy bordering on fetishism. “I care for my pieces almost as though I were treating them,” she explains of a body of work that demands precision, detail and thoroughness. When she attaches brown fasteners to the wall and threads a rope through them, they evoke the even, intimate, crossed lacing of a corset. Like with her zips, she dissimulates the ruse with filler and paint, which she applies layer by layer and smooths for hours, painstaking work that is doubled by a more explicit pain: when Wertenbroek pinches and twists leather, for example, she imagines piercing skin with a needle. “These pieces of leather are actually pieces of the body!” she says, summing up the sensuality and suggestive violence of her techniques.

But behind the luxurious surface of these delicate creations also lie more trivial inspirations. Fascinated by the liberating role of carnival in medieval Europe, Wertenbroek transposes taboos into her works, like intestines whose membranes are stretched and compressed in the same way as her red leather. The pretzel, one of her favorite themes, emerges in sculptures made of painted bread whose shape is at once a grimacing face, an ouroboros [a snake eating its tail] and excrement. Simultaneously attracted by the texture and preciousness of the pretzels and repelled by their inedible composition and fecal form, moved by the almost erotic excitement of the zipper and the frustration of not being able to open it, the viewer is trapped in her paradoxes. More cynical than they appear, Wertenbroek’s works bring humour to the gallery: where Anzieu penetrated patients’ psychic membranes to discover the twists and turns of their consciousness, she mischievously lifts the skin curtain of intimacy to reveal the mysteries of the self, exposing her own vulnerability with courageous temerity.