3

3

Death of Richard Serra, the artist who turned sculpture into architecture

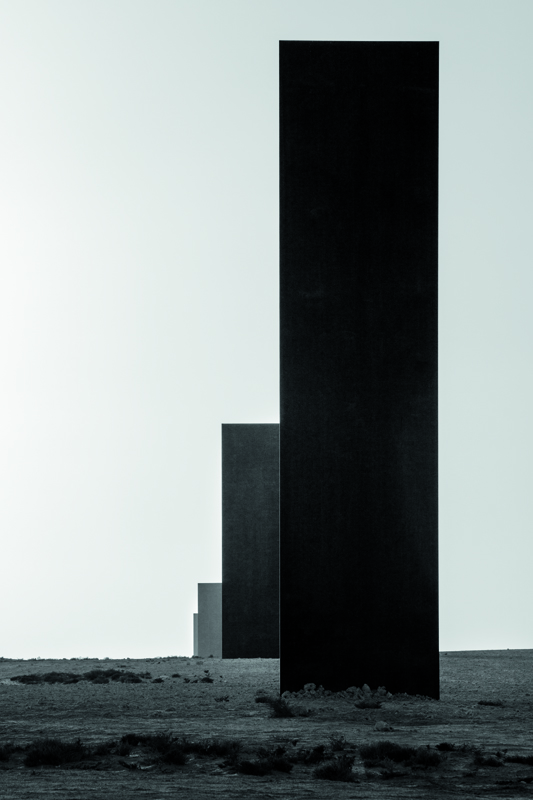

From the late 1960s onwards, Richard Serra (1938-2024) has revolutionized sculpture with his gigantic lead and steel installations, first set up in natural landscapes, then inside the world’s greatest museums. The American artist died on the night of Tuesday, March 26th, at the age of 85. Throwback to one of his most powerful works, East-West/West-East, captured by photographer Aitor Ortiz in the vastness of the Qatari desert in 2020.

Text by Thibaut Wychowanok,

Photo by Aitor Ortiz,

Introduction by Camille Bois-Martin.

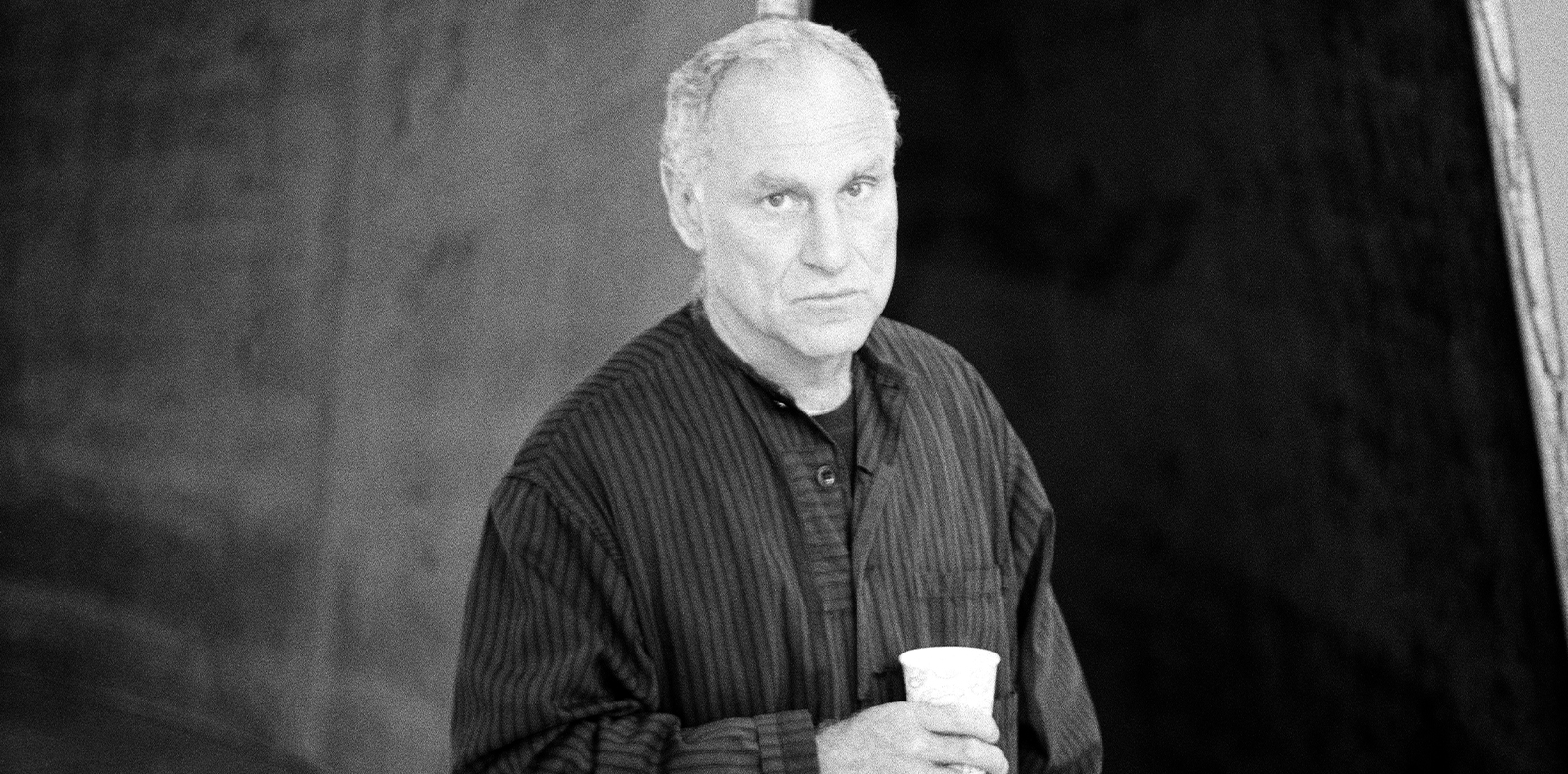

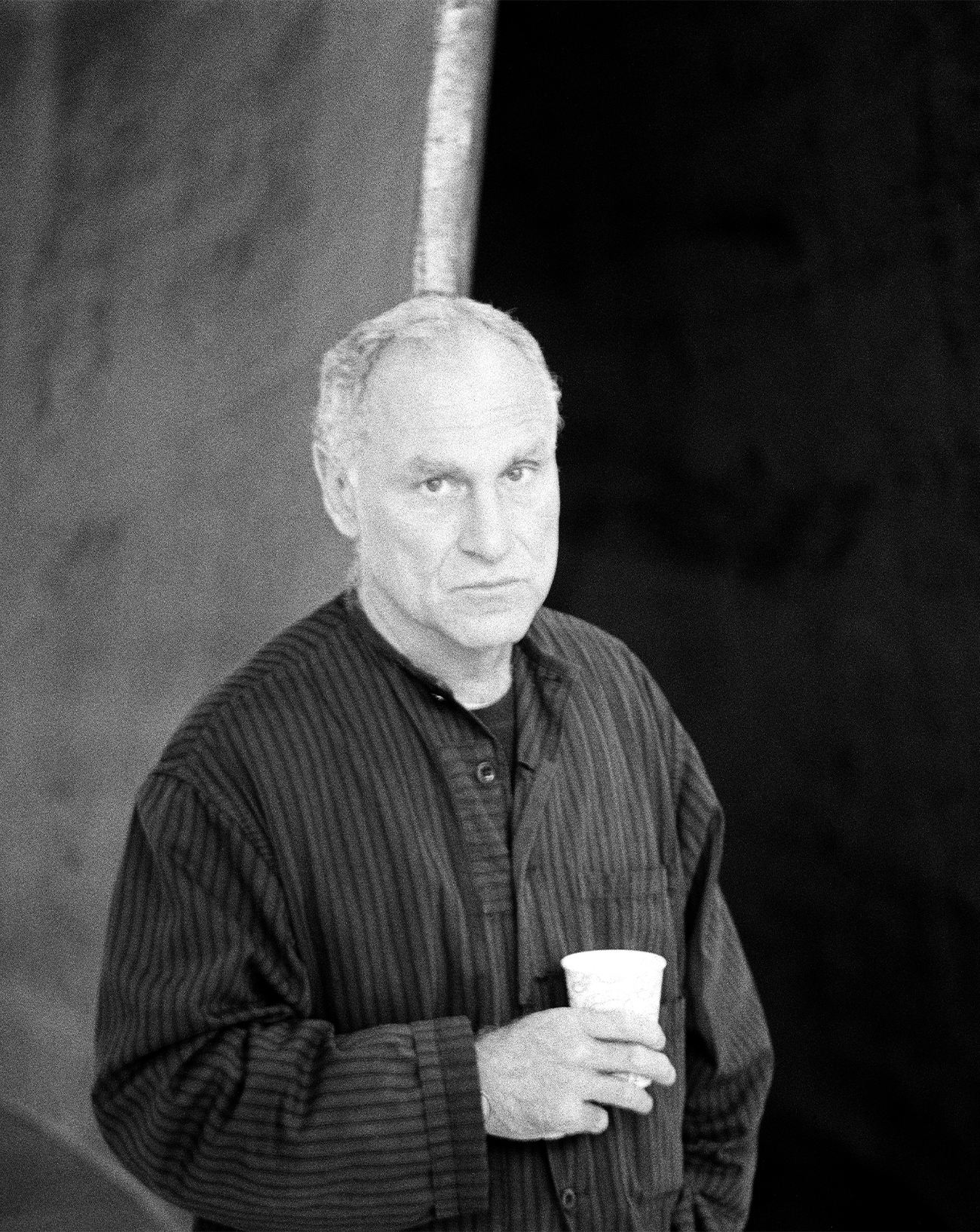

The leading figure in abstract sculpture, American artist Richard Serra passed away

On Tuesday, March 26th, the contemporary art world lost one of its most historic figures. Richard Serra died of pneumonia at the age of 85. With his five decade long career, the American has greatly contributed to the radical turnaround in Western sculpture as early as 1969, as he unveiled One Ton Prop (House of Cards), a cube made up of four one-meter-long lead plates. There, the principles that would later govern his practice were established – the use and alteration of metal, lead in particular, the lack of figuration, and the creation of elemental forms with pure, radical lines. Born in California in 1938, the American artist grew up among the work tools of his Spanish-born father, a welder in a San Francisco shipyard. After spending endless summers working in steel mills, the young man studied art at the Yale School of Art and Architecture before traveling to Europe, where he discovered the work of Brancusi (1876-1957), who was a revelation to him.

Fascinated by the pared-down curves and volumes of the Franco-Romanian artist’s sculptures, Richard Serra abandoned painting to dedicate himself to sculpture, working with every metal he used to be in contact with as a child. Oscillating mainly between weathering steel and stainless steel, he gradually erected metal plates to build architectural installations that are both imposing due to their immensity – they reached 78 feet high in Qatar in 2011 – and enveloping because of their shapes – they feature straight lines, such as the rectangular, triangular or trapezoidal structures, or curved ones, like spirals, waves, semi-circles… The scale of these structures determines the flow of visitors and transforms their spatial experience, to the point of losing them in their labyrinthine meanderings. Still, one characteristic color remains, that of the rust of weathering steel, also known as Corten steel, which has eventually become his signature.

In 1972, the artist published his own sculpture manifesto, listing several hundred verbs linking his practice to physical movements and actions: “Curve”, “Split”, “Press”, “Heat”… Although Serra’s approach brings him closer to his minimal and conceptual art counterparts, such as Carl Andre, Tony Smith, Bernar Venet, he distinguishes himself by the monumental dimensions of his works exhibited all around the world, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the MoMA in New York.

Numéro takes a look back at one of his flagship projects, a series of gigantic rectangular steel slabs, erected by the sculptor in the sandy plains of the Qatari desert in 2014. In 2020, photographer Aitor Ortiz visited the site to shoot a series for Numéro…

Artist Richard Serra erects monoliths in the Qatari desert

Among sand dunes and in spite of the scorching heat that often exceeds 40°C, four 50 feet high steel plates cast their seemingly infinite shadows onto the ground, like black brushstrokes on a canvas of sand. Since 2014, American artist Richard Serra’s installation East-West/West-East has punctuated a desert, lunar and sublime landscape located 50 miles away from Doha. The term sublime is to be understood in its original meaning, as the artwork raises our awareness about the fragility of mankind in the face of the omnipotence of the world, in the manner of 19th-century German Romantic painters, such as Caspar David Friedrich. Except that here, the viewers can wander around inside the painting. In fact, they can paint it to some extent, depending on their viewpoints – on top of the dunes or diving headlong into the deep shadows – and on the time of their visit, during the day or at night.

The desert wasn’t an obvious choice for the 80-year-old artist born in San Francisco by the seaside, and whose madeleine de Proust was the gigantic metal silhouettes of the ships cutting sharp the horizon at the shipyard where his father used to take him. However, the invitation sent by the true culture queen of the kingdom, Sheikha Al-Mayassa, princess and chairwoman of Qatar Museums, might not have been so far-fetched. In 2019, Richard Serra told The New York Times that the sea was “like the desert with water”.

The man who is now considered as the world’s most famous American sculptors has not always worked with steel, monumental curves open to welcome visitors, or large vertical slabs – Parisian audiences can remember his installation at the Grand Palais in 2008. In the 1960s, the young artist, who freshly graduated from Yale, tried his hand at painting, while financing his education by working in… a steel mill. Shortly after, during a stay in Paris, Richard Serra discovered Brancusi’s studio, which was reconstructed by the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, as well as the work of Giacometti in particular. His fascination with steel thus gained an artistic purpose – the artist tranlated the weight, density and gravity characteristics of this industrial material into plastic qualities.

In the same 2019 interview with The New York Times, the artist explained that “if you’re dealing with abstract art, you have to deal with the work in and of itself and its inherent properties”. Radical, simple and austere, his pieces never intended to convey a political or social message about the context in which they were integrated. They represent their sole point reference. They conjure up mental experiences of the physical force of the world for the viewer. Yet, it doesn’t prevent them from raising metaphysical questions about humanity. In Qatar, these large plates of rusted steel draw endless minimalist and abstract reinterpretations of Giacometti’s Walking Man, a figure whose irresistible momentum and weary inclination are reminders of his frailty. Power and vulnerability are at the core of Serra’s works. They proudly rise up to the sky, all the while suffering from the wind, sand and sun. Steel then takes on hues of ochre, red, orange, brown and amber, in the manner of an alchemical canvas in constant evolution until it withers away.

It was in 1969 that the artist turned to industrially manufactured Corten steel. The Qatari slabs were crafted in Germany and then shipped to Doha. There, they were turned into funerary monuments of the desert erected to the glory of mankind in all its fragility and omnipotence – a human embodiment of the Vulcan god, whose creations reach for the stars. “What I make is the opposite of an object,” Serra shared to Le Monde in 2008. “I create an object with a subject – the person who will enter it and experience it. Without that person, there is no artwork.”

Faced with the artist’s monolithic menhirs, which are reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Stonehenge standing stones, men are compelled to fully measure themselves against their own creations. They surpass them, but still are nothing compared to the vast expanse of sand and of the star-filled sky. “I don’t want to place sculptural objects in a space, but rather to fit the entire space into a sculpture,” Richard Serra explained to Le Monde. The blades of steel cut through the space and recompose it, forming a yardstick that measures its infinity.

Traduction Emma Naroumbo Armaing