6

6

Interview with David Chipperfield, the architect who dreams up new cities

What will the ideal city look like in 20 years’ time? This is the question that british architect David Chipperfield and his young swiss confrère Simon Kretz spent 24 months thinking about as part of Rolex’s Mentor & Protégé programme. Numéro asked them what answers they’d found.

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok.

For the past two years, the brilliant minds of British starchitect David Chipperfield and his young Swiss confrère Simon Kretz have been joining forces to think about the future of our cities. They came together under Rolex’s Mentor & Protégé programme which, every two years, brings together an established heavyweight and a young talent in artistic fields such as music, art and architecture. Their only obligation: to spend two years together coming up with ideas for a better world. Chipperfield and Kretz have been thinking about how the design of cities – where 54% of the world’s population now lives – might be improved. Numéro caught up with them as they went to press with their conclusions, which will also be the subject of a lecture series in Berlin.

NUMÉRO: One of the principal challenges for cities in the future is the question of the new and the old – how much should our architectural heritage be preserved? Which is better, Paris’s museum approach or London’s building frenzy?

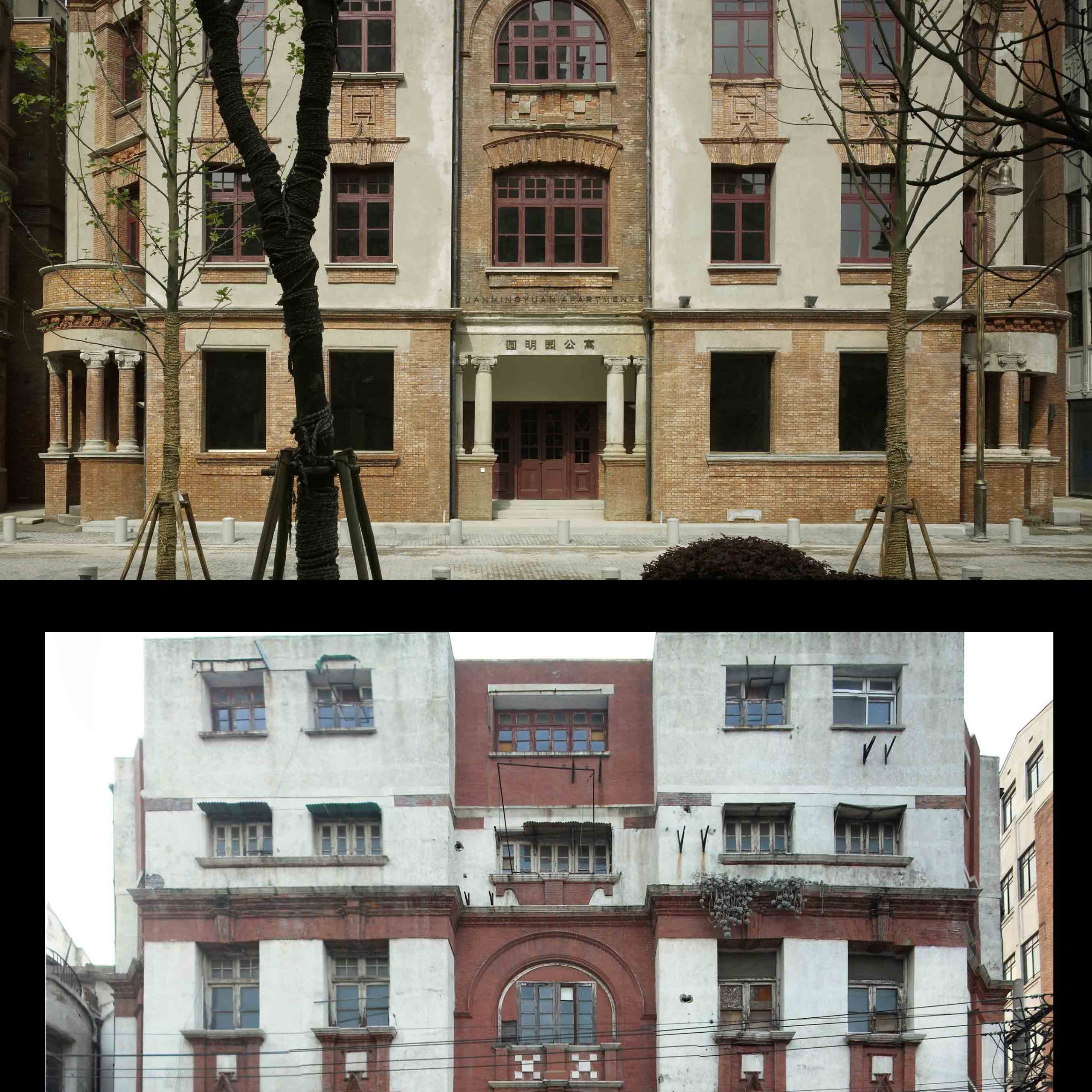

DAVID CHIPPERFIELD: Let me tell you two stories. The city of Munich asked my advice with respect to a development that involved destroying buildings from the 1950s. Were they architecturally interesting? No, rather mediocre. And yet they’re part of Munich’s memory. Destroy them, and it’s a whole chunk of the city’s soul and history that disappears. In Shanghai, I was involved with a development concerning a building on the north of the Bund. The developers wanted to demolish it. Once again, it was mediocre, but the authorities, who are becoming more sensitive to the idea of preservation, wanted it kept. In China, the simplest solution is to demolish and build an exact replica but with better materials. The Chinese are amazing when it comes to copying! I had to fight to convince them that we needed to work with the existing architecture. But after ten years of restoration, I couldn’t help saying to myself, “My god, all that work for this?! You’d think we hadn’t done anything at all.” But something interesting has happened since: people often stop to take photos of our building. Just nearby, another building has been demolished and replaced by a copy. And guess what? Nobody stops to photograph it.

“The problem with towers, as I see it, isn’t so much that they spoil the landscape – the problem with towers is on the ground at their bases!” David Chipperfield

Imagining the city of the future… Isn’t that rather a quixotic exercise in an age of anarchic megalopolises such as Shanghai?

DAVID CHIPPERFIELD: As a society we have indeed relegated all ideas of urban utopia to historical limbo. But it has to be said that the utopias of the 20th century generally turned out rather badly… What have we done instead? We’ve put in place a laissez-faire system, a blank cheque given to property developers who are supposedly devoid of all ideology this time around. Except that in reality what’s going on, particularly in American or British cities, such as London, is a logic of free-market liberalism that is just as ideological. Developers have all the power, and their primary goal is maximum return on their land, an increase in rental value that sets off a process of gentrification, a multiplication of towers to maximize the profitability of each and every square metre… Around 100 towers have been built in London over the past ten years, and another 300 are planned! Public authorities have been relegated to a role of oversight with respect to urban development – the “develop- ment control board” as they call it – which, in reality, is no longer globally planned in advance. There’s no proper planning anymore.

SIMON KRETZ: Because economic factors have imposed a narrative which claims that the municipality and the state are incapable of pro- ducing efficient urban planning.

For the past two years, you’ve been working together under Rolex’s Mentor & Protégé programme to come up with models of ideal urban development. What conclusions have you drawn?

SIMON KRETZ: The first publication that’s come out of this process doesn’t claim to offer readymade solutions. And it’s not so much that architects’ or developers’ schemes are necessarily bad, but rather that their manner of evaluating projects is problematic. We absolutely have to consider the effects of our planning decisions beyond the particular site concerned. If you’re a developer, you build your tower and along with it the car park that you think you need. But if you look at the situation on a larger scale, if you enlarge your perimeter of analysis, perhaps actually it would be more profitable (both for you and for society) to renovate an underused car park nearby?

DAVID CHIPPERFIELD: The main problem with today’s development plans is their inability to provide decent public space. The interconnections between the architectural project and its environment aren’t taken into account. We find ourselves in a situation like in Doha where the streets have disappeared. Nothing links the towers to each other. The problem with towers, as I see it, isn’t so much that they spoil the landscape – the problem with towers is on the ground at their bases!

The book On Planning. A Thought Experiment by David Chipperfield and Simon Kretz would be available in February at Koenig Books, www.koenigbooks.co.uk , and at the Serpentine Gallery, www.serpentinegalleries.org

Conferences and closing ceremony of 2016-2017 cycle Rolex’s Mentor & Protégé programme in Berlin, 3 February 2018 – 5 February 2018, www.rolexmentorprotege.com