9

9

Nanténé Traoré, the photographer of absence exhibited at Reiffers Art Initiatives

The work of photographer Nanténé Traoré is being shown until May 10th as part of the exhibition “1000 milliards d’images” at the Reiffers Art Initiatives in Paris.

Portrait by Jonathan Llense,

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok.

Published on 9 May 2025. Updated on 30 July 2025.

Interview with photographer Nanténé Traoré

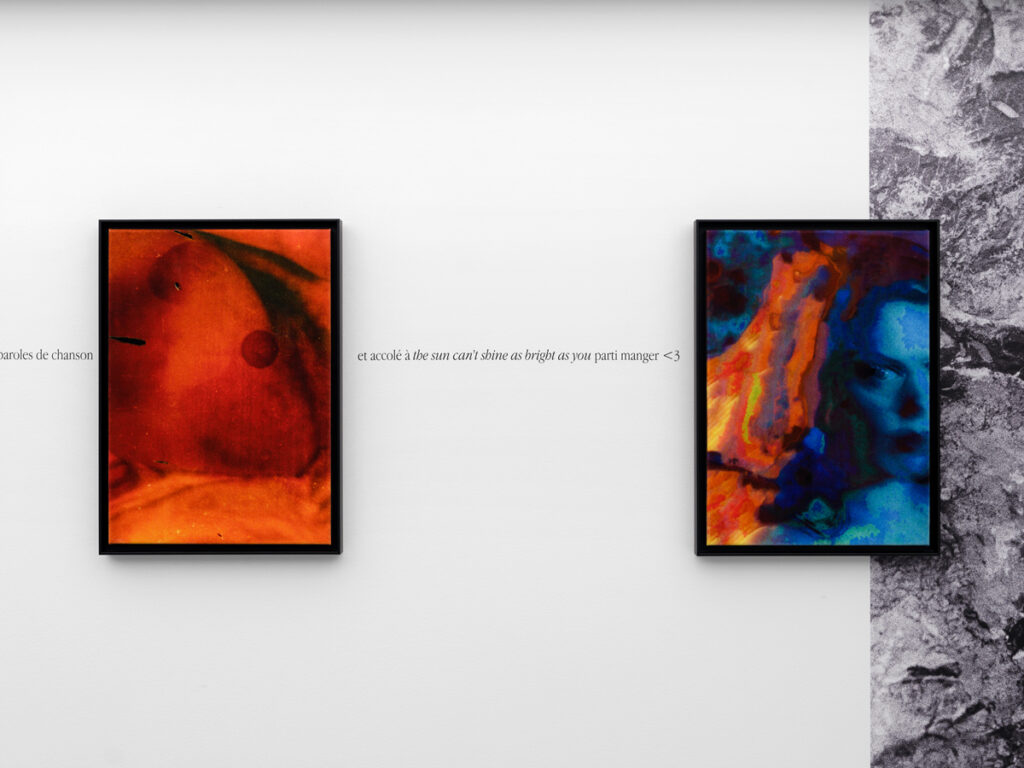

Numéro art: How did you create the images displayed in the exhibition “1000 milliards d’images“? I’m deliberately using the word “images” rather than “photographs.” Nanténé Traoré: The process is quite long between the moment the photo is taken – I only work with film – and the moment when the image itself is created. Very few of my photos are used just as they are, they’re always altered in some way, either by cropping or by intervening in the printing process. There’s also a found image in the exhibition – a screen capture of a video I sourced online.

I tried to find out where it came from, but couldn’t identify its origin. In fact, I printed it out in 2013 to make a mixtape for my boyfriend at the time, and it’s a scan of the CD. In the photo you can see some reflection on the plastic… I like the fact that this image is a hybrid, both a scan and a found thing. All the other images are printed from out-of-date film that I process myself. I fiddle about in the dark room to make the photos look the way I want them to. I have them printed either on paper or on velvet, like the ones in the exhibition. I use a wide range of techniques to manipulate them, from intervening directly on the film to working on fiber.

Why did you choose to print the images on velvet for the exhibition? It’s a very difficult material to work with. The velvet is brushed against the pile and is extremely pale. So, to ensure contrast in the images, I had to brush the fiber many times very gently so that it lay in the right direction. I started working with velvet quite recently, but what I like about its being a difficult material is that it goes against the idea that a photograph can be duplicated. There is too much human intervention in these pieces for them to be identically reproduced. They’re one-offs.

And that’s what I’m interested in: how a technique – photography – that is supposed to make images widely accessible and render them reproducible can create unique works, not in terms of format or what they say, but in the way they were made, in the margin of error that occurs at each stage with human intervention.

Printed on velvet, the images become yet more abstract the closer you get, which is perhaps a form of disappearance. Indeed absence and disappearance run throughout your oeuvre… Yes, absolutely. The idea of the absent image, of what’s missing. Photography and images, as a general rule, are always subjective, because you frame them. So there’s a whole life that I’ve decided not to show around what is on display. For me, the way you frame the image is just as important as how you print or alter it.

It all starts with framing. The alterations I make to the film also permanently erase certain things, and I have to get over my regret for these potential images that will never exist. The process required me to gain knowledge in physics and chemistry, but also to look at what the pictorialist photographers were doing in the early 20th century. How have we approached photography in the past 100 years? What has already been done? All the techniques I use existed in 1890…

The exhibition is not just about framed images, it’s a very precisely crafted installation, like a kind of open narrative. This series is about where I come from, namely the Internet and Tumblr in particular, where I used to collect images found online and place them next to each other to see what they revealed. In a way, the installation is a kind of collage. It uses the codes of people who have spent too much time online, who have collected too many images, who have designed mood boards, who have stuck images on their bedroom walls. It’s very similar to my bedroom as a teenager. But how are these images perceived by the public? This is beyond my control, and so much the better – I’m delighted that everyone’s imagination can express itself and go beyond what I wanted to convey.

What can you tell us about the phrases that appear throughout the exhibition and on the images? They connect the pieces together. I’ve always written poetry, plays, and essays. These texts date from my adolescence. They speak of the time I spent online and of everything I remember about it, something most people born between 1990 and 2000 have in common. I wouldn’t be making images if I hadn’t had the Internet. Talking about this in this context helps me. When I was younger, I studied film in secondary school.

I remember a quote from Robert Bresson who said that the eye and the ear don’t work together. He said this to explain why, in a film, there shouldn’t be both music and images. We are not capable of perceiving and managing them simultaneously. I often think of this when it comes to combining text with images. This is a lot of information – it requires large enough spaces so that the one doesn’t drown out the other.

Nanténé Traoré’s artworks are on display until May 10th, 2025, in the exhibition “1000 milliards d’images” at Reiffers Art Initiatives, Paris 17th.