9

9

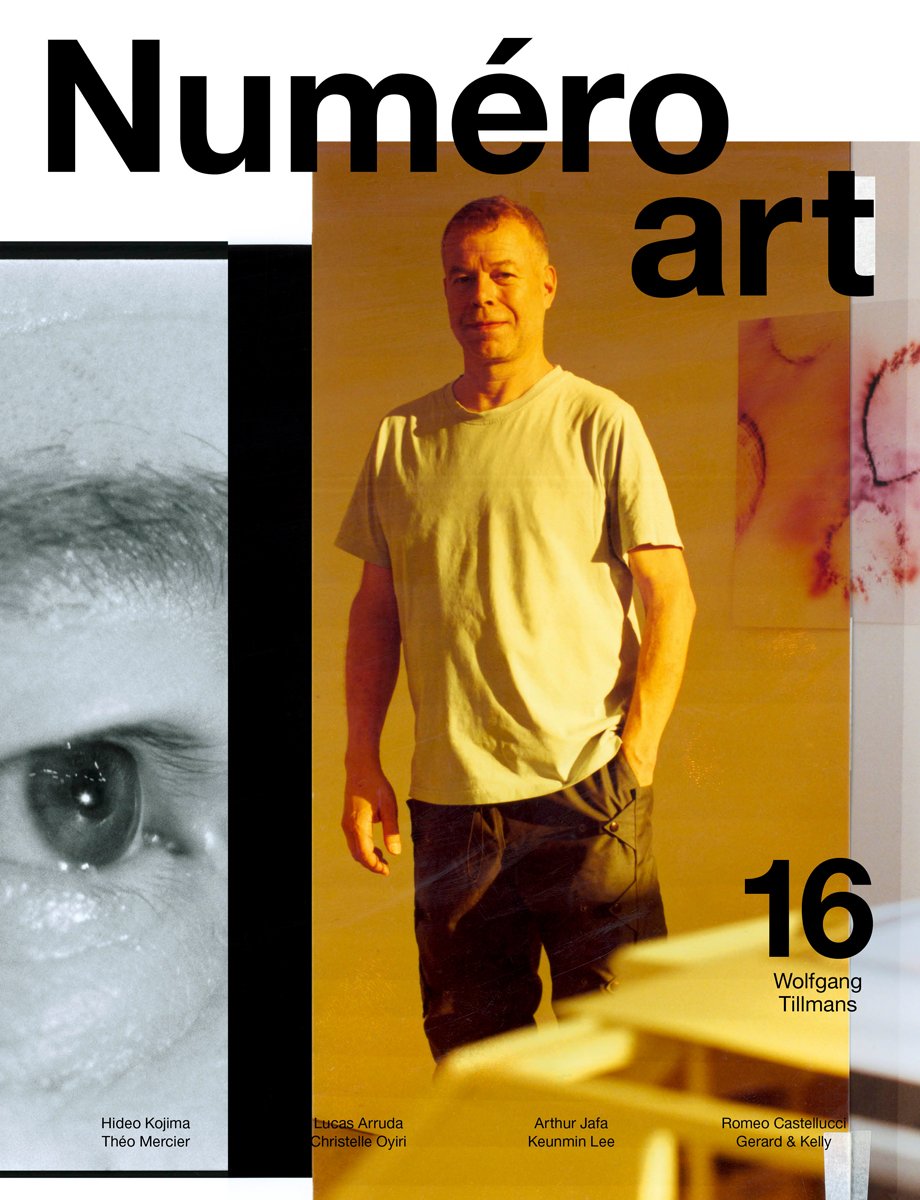

Interview with Wolfgang Tillmans, the photography maestro exhibited at the Centre Pompidou

Before Paris’s Centre Pompidou closes its doors for a five-year-long renovation, the artist Wolfgang Tillmans is taking over the 5,000 m2 of the Bibliothèque Publique d’information – the building’s famous library – where he will be putting older works in dialogue with newer pieces. Interview

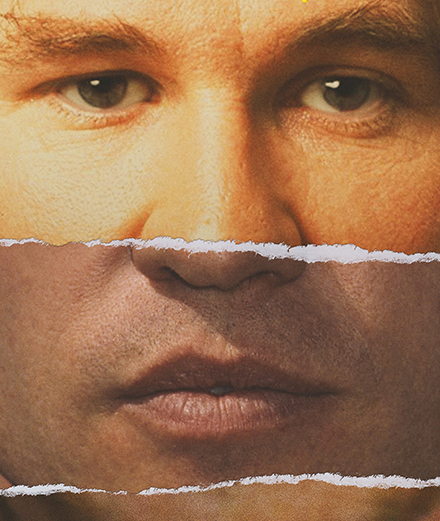

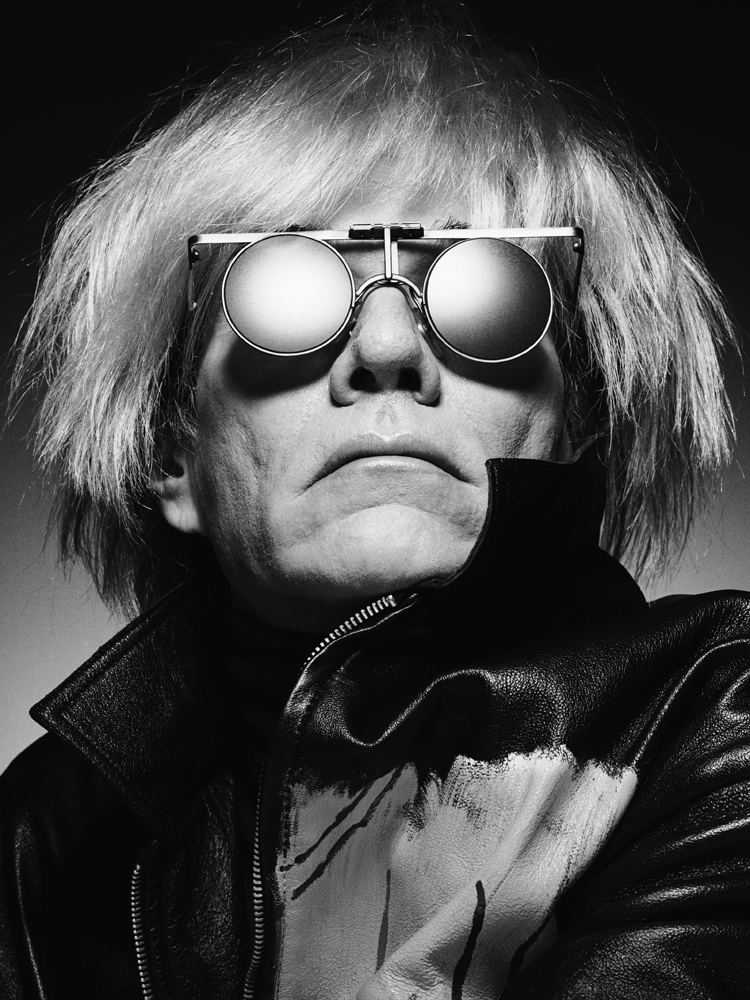

Portraits by Suffo Moncloa ,

Interview par Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 9 June 2025. Updated on 29 July 2025.

Numéro art: This summer, you’re putting on the final solo show at the Centre Pompidou before it closes for five years. You’ll be taking over an emblematic part of the building, the Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI), which has been emptied of its 430,000-strong holdings. How did you approach this ambitious project?

Wolfgang Tillmans: For each exhibition, my general departure point is the physical space where I’ll be showing my work: the venue, the city, and my history in that city. Then I think about the audience, both local and visiting, that will see the show. The final consideration is the exhibition’s place in may career, with respect to both what went before and what will come after. In Paris, my last big show was 23 years ago at the Palais de Tokyo, in 2002.

As soon as Laurent Le Bon and Xavier Rey [respectively, the president of the Centre Pompidou and the director of the Musée national d’art moderne, ed.] offered me this carte blanche, in 2022, they told me I could use the the BPI, which is a completely open space. So we’re coming back to how Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers originally imagined the building, which is to say entirely free of columns and walls. Very soon after the museum opened, on all the other floors, the curators started putting up walls, so that only the BPI remained entirely open plan. This carte blanche allows me to explore the building’s past as well as its future.

“I really see my exhibitions as performances through which, each time, I reveal different layers of myself.” – Wolfgang Tillmans

You’re always very involved in the preparations for your solo exhibitions, often delving back into your archives to create new dialogues between photographs, series, themes, and eras. How will this exhibition differ from your big 2022 MoMA retrospective, which looked back over 30 years of your career?

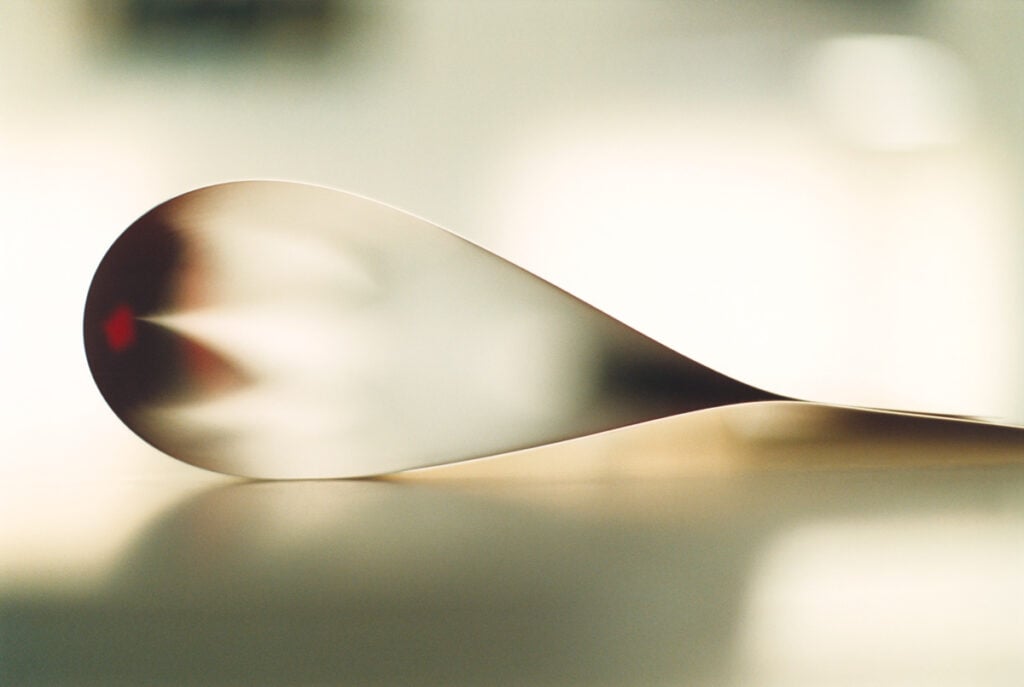

My MoMA show was a chronological retrospective from the late 80s to 2022, which was very atypical for me. Chronology won’t come into it at the Centre Pompidou. Since we’re in a library, the show will include a lot of print and paper, because I love making and publishing books, I love newspapers, and I sometimes see myself as a journalist. But I also want it to be playful. Some sections will explore my different types of abstractions on paper – the Paper Drops, the Lighters, the Silvers, and so on.

I’ll focus on certain themes in my work, too, such as water. I’ve also been thinking about what I’ve produced in France since I started out, which is why you’ll find works I made in Reims in 1985. Moreover, for the first time in a decade I’ll be showing Memorial for the Victims of Organized Religions, a grid of 48 almost-black prints I made in 2006 after realizing that there are memorials everywhere but none for the victims of organized religion.

You’ll also be unveiling a film you shot in the library before it closed. I wanted to pay homage to the BPI, which is visited and loved by so many people. Since we couldn’t just film library users, especially not with a hidden camera, we invited invited 60 readers to come on a day when the library was closed, and filmed and photographed them as they moved freely through the library. We had no idea what would happen, but in the end it turned out to be an exact living replica of a normal day at the BPI! The film will be shown on the self-learning monitors. I also recorded the sound of the library that day, and I’d like to broadcast it in one of the exhibition spaces. You might think a library is silent, but in reality that silence is very alive given everything that’s going on.

The challenge of a carte blanche can be very exciting but also rather nerve-wracking when you have 5,000 m2 to fill…

“Doing what you want” is indeed a little difficult when you’re primarily a wall-based artist and there are no walls! I always think about sustainability in museum shows, and I try to use what’s already there rather than tearing out the previous exhibition design. It was clear that we weren’t going to fill the BPI with walls that would then be demolished, so I’m keeping some of the furniture, such as shelving units, just as it is, and building other pieces. The tables will serves as display cases. Two 15 m-long shelves will contain books from the library’s ten categories – I’m hoping there’ll be a certain beauty in seeing all that condensed knowledge displayed in this way. On the longest wall in the library, the corridor where no one has ever hung anything, I’ll be showing large, unframed prints.

Given the project’s ambition and complexity, did you hire architects?

When I first received the Pompidou invitation, I thought I’d hire a whole team and expand my studio. In the end, I worked hand in hand with Florian Abner, the chief curator of photography, and the architect and exhibition designer Jasmin Oezcebi, who put all her knowledge and expertise at my disposal to help realize my vision for the space. I was very lucky. A lot of the show’s poetry is also about what you don’t see, what I didn’t do.

While I was working on it, I often asked myself: “What do I change and what do I leave intact?” One of the main interventions will be a space delimited by a big video wall and a large silver curtain in which I’ll show a new piece that mixes sound and moving images. I’ve long been critical of LED walls, which, given their cost, I see as gestures of power on the part of certain artists. But it makes sense here, since it serves to light the space as well as to show my images.

“My early passion for astronomy gave me a strong sense of geometry and framing.” – Wolfgang Tillmans

People have often described your oeuvre as a diary, an interpretation that you refute. Where does this misconception come from? In the mid 90s, when I first became known, people talked a lot about the “authenticity” of my work. So I began insisting on the fact that my photos were staged. “No, these young men didn’t just spontaneously sit down half naked on a tree branch!” [Laughs.] The feeling of authenticity I was seeking was very different from Nan Goldin’s, for example. My work is only a diary in the sense that it was made in places where I was physically present, when traveling or in Berlin, where I live.

But, for example, when I was making my still lifes in the early 90s, I was seeking to show the physicality of a melon, how the juice oozed from the pulp, something very universal. I never photographed fruit in order to say, “Look what I ate!” I’m not some kind of Instagram predecessor! All I want is that, when looking at my photos, people feel a certain familiarity with what I’m showing and that it creates a moment of exchange around a shared experience.

This desire for a universal language also comes through in the many astronomical references in your work, as well as on your Instagram account, where you regularly post astronomical phenomena that are visible to the naked eye. How has this childhood obsession shaped your artistic outlook? When I was a child, I found this little book on astronomy in my parents’ bookshelf and became completely obsessed with it for the next four years. The feeling of solitude in the face of the infinity of outer space didn’t make me feel sad or afraid – on the contrary, it gave me a sense of solidarity through a shared condition. At the beginning of my career, I put the science side of me on the back burner until the day in 1998 when I saw a total eclipse of the sun in Aruba, in the Caribbean, something I’d always dreamed about as a boy.

“The European cause is more alive and urgent than ever.” – Wolfgang Tillmans.

From that point on, astronomy came back into my life as an artistic concern, and I began to work on space and perception. In the early 2000s, my series focusing on skies and horizons allowed me to explore the question of borders and frontiers: in these pictures, the division appears very clearly when seen from a distance, but as you approach it disappears.

In 2016, some of these works became the background for my anti-Brexit posters, since the referendum was essentially about borders. Now, looking back, I would say this early passion for astronomy gave me a strong sense of geometry and framing, and also taught me the importance of exact observation when you reach the limits of the visible.

You’ve been campaigning for a strong, united Europe for a number of years now. In fact, today you’re wearing one of the T-shirts you designed for the 2019 European elections, and you also campaigned in last year’s European elections. Will this political engagement be present in the exhibition? A whole section will be devoted to Between Bridges, the exhibition space I’ve been running for 18 years in London and Berlin [and which, in 2017, saw the birth of a foundation committed to humanism, solidarity, and the advancement of democracy and that supports the arts, LGBT+ rights, and the fight against racism]. There’ll also be a space at the BPI for my European election campaigns, such as the 2019 slogan “Vote together, vote for Europe,” which seems particularly relevant right now in the face of the orchestrated attack on the European Union from the likes of Trump, China, and Russia, who are seeking to break our continent’s unity, while Elon Musk is actively meddling in German politics. The European cause is more alive and urgent than ever, and my implication in it will never have been more visible than in this exhibition.

The title of your MoMA retrospective was To Look without Fear, a powerful and optimistic message. At the Pompidou you’ve chosen Rien ne nous y préparait – Tout nous y préparait [Nothing Prepared Us for It – Everything Prepared Us for It], which speaks more of duality and the limits of action. Is there a connection between the two? The Pompidou title came to me out of a strong personal feeling but also, of course, with respect to the current state of the world. On the one hand, everything that’s happening politically, ecologically, economically, and culturally seems like a surprise, but on the other it’s far from it. There are a lot of things we could have seen coming – I’m not pointing fingers at anyone, I consider myself just as blind – but on the other hand we can’t be responsible for everything and we can’t know everything. This title is about that. But I also insist on the possibility of looking reality in the face without fear or preconceptions.

In 2016, you returned to music 30 years after the release of your first EP. Since then, you’ve brought out two albums, including last year’s Build from Here. Are there parallels between the way you compose tracks and images?

I see recording as a way of photographing sound. I use a lot of field recordings and samples, but I’ve also noticed that, when I record a sound, I’ll always end up using that first recording, whereas most musicians will record several takes in the studio. It’s the same with photography – I never say to myself, “Oh, that’ll do for today, I’ll shoot that same paper drop tomorrow.”

Even if the paper drop stays put exactly where it was, the scene will be completely different, because the light, but even more so my brain chemistry, will have changed. I see the creative moment as an intersection between time, space, the brain, the past, technique, presence, availability, and so on. Getting all these parameters to come back together in exactly the same way is very difficult to achieve.

I imagine the same applies to your exhibitions: although they sometimes feature prints we’ve seen before, they all grow out of completely different circumstances. Exactly. My exhibitions are the result of spending several weeks in a particular space and of choosing what and what not to show. I really see them as performances through which, each time, I reveal different layers of myself.

You’ve always given great importance to the materiality of images and the way they’re combined and displayed – framed or unframed, sometimes attached with pins. Over the course of your career, have you observed changes in the way photography is exhibited?

When I started using deep frames in the late 90s, no one was doing it. The technique I developed, which consisted in floating the print in the frame so that there’s air both in front of and behind it, broke all the rules for displaying photography at the time. It has since become quite common, and my way of hanging works has often been imitated. But even after ten years of Instagram and an incessant proliferation of images, I can always recognize my own work! Which goes to show that photography, even though it’s still perceived as just a technical medium, is in fact very deep from a psychological point of view.

Wolfgang Tillmans, “Rien ne nous y préparait − Tout nous y préparait”, exhibition from June 13th to September 22nd, 2025 at Centre Pompidou, Paris 4th.

As the main partner of the exhibition, the house of CELINE is offering four open-access visiting days on June 13th, July 3rd, August 28th, and September 22nd. Buy your tickets here.