29

29

Disco, Buddhism and queer icons: Gerard & Kelly unpack their work

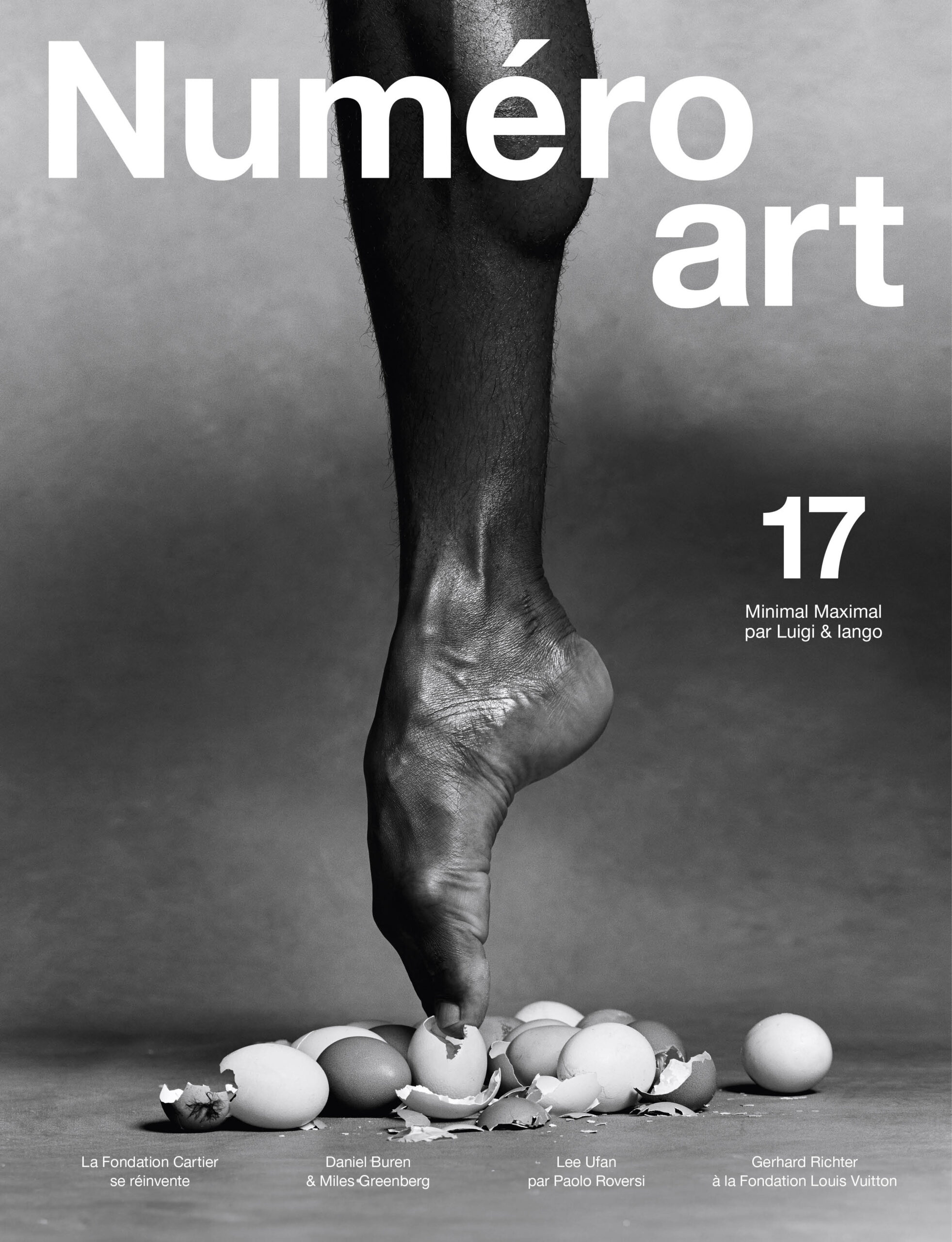

This spring, the American artist duo showed a fascinating exhibition at Paris’s Marian Goodman Gallery, the occasion for Numéro art to catch up with them to discuss the major themes that inform their oeuvre, from their positioning with respect to architecture, art history, and the body to the importance of exercising a queer sensibility.

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok.

Published on 29 May 2025. Updated on 29 July 2025.

Numéro art: What’s the significance of Bardo, the title of your recent exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris? Brennan Gerard: The title comes from Tibetan Buddhism and refers to the transitional state between death and rebirth during which our consciousness undergoes profound changes. In the exhibition, we evoke three openly or symbolically queer historical figures who long remained in the shadows. These three figures belong to the Bardo because, though they’re dead, they are still very present in our lives. There’s Eileen Gray [1878-1976], the designer and architect, renowned for a major work of architectural Modernism, the Villa E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. This is where we shot the video shown in the exhibition.

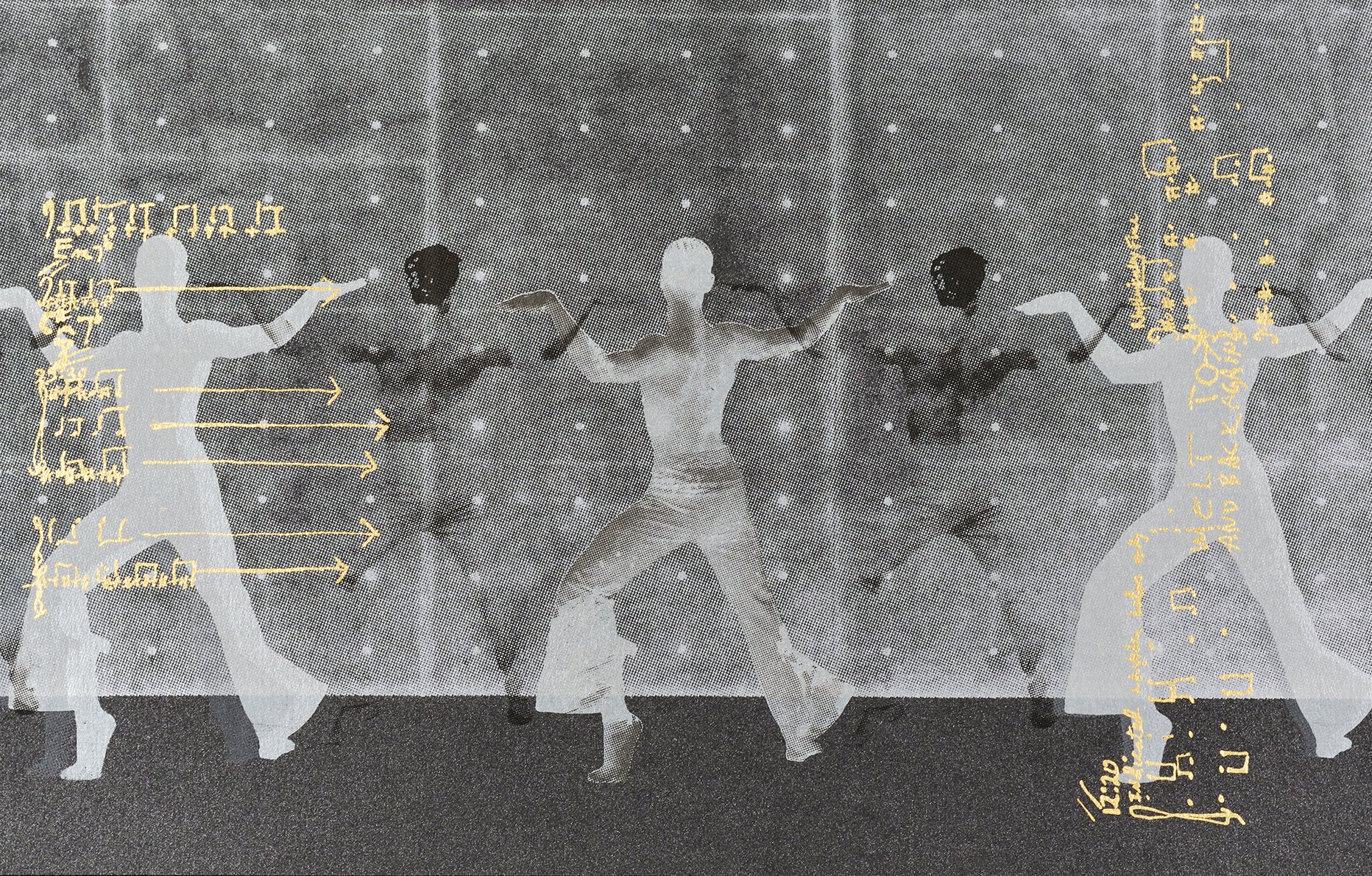

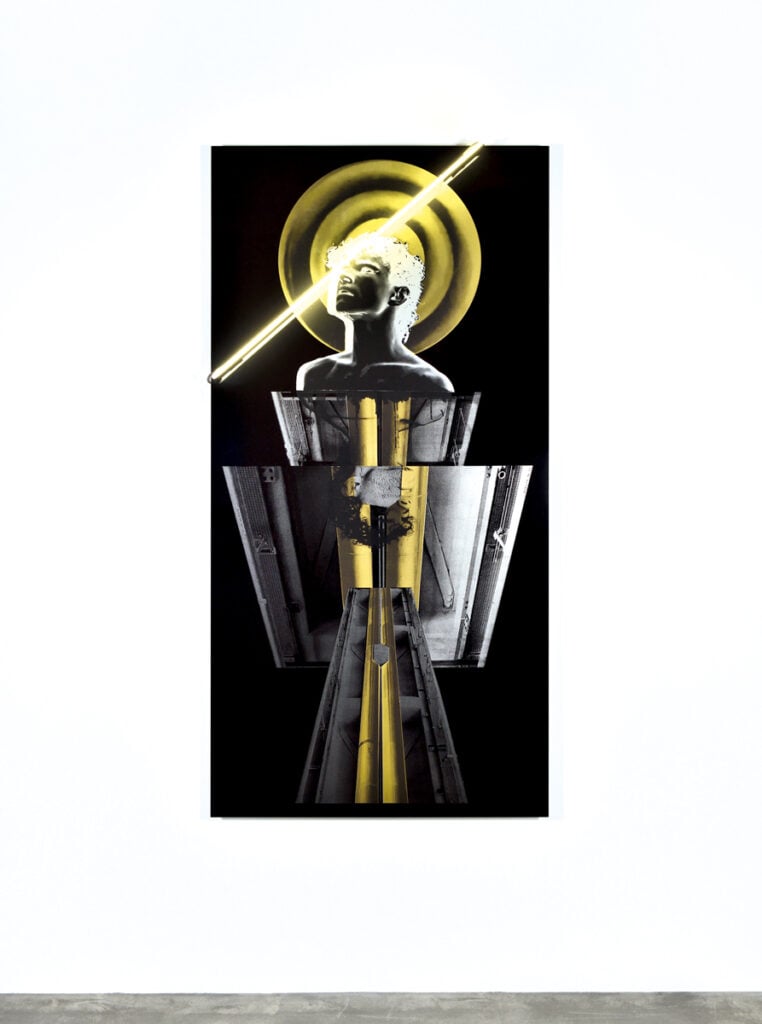

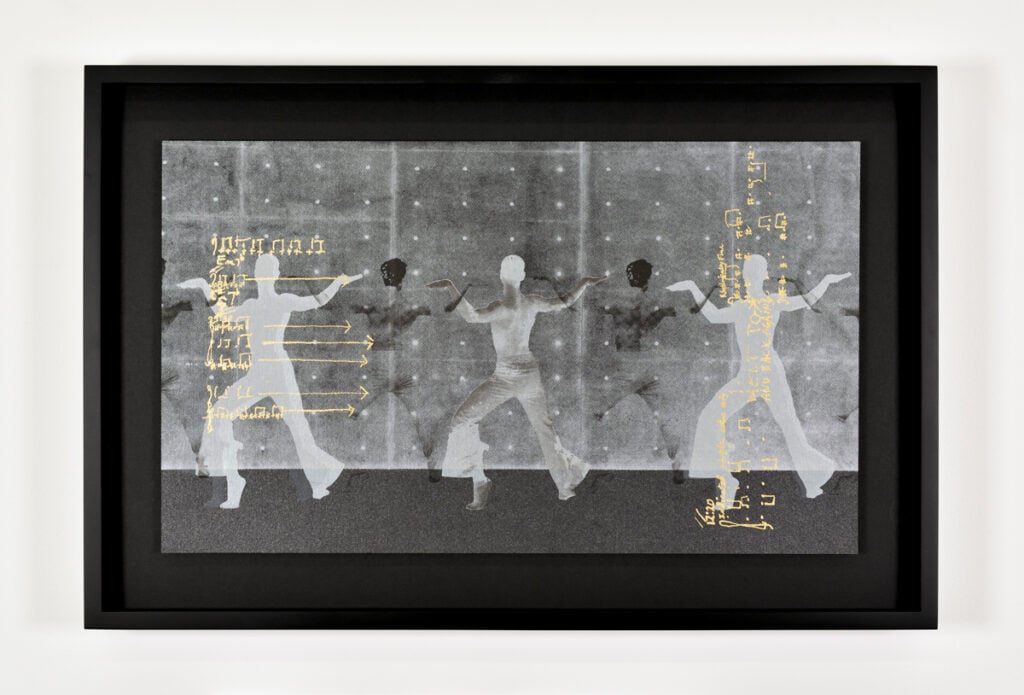

Then, in the vaulted gallery space, we focused on Francesco di Stefano, known as Pesellino [1422-1457]. A prolific painter, he worked for the Medici in Florence and collaborated with the foremost artists of his time. He died young, aged 35, from the plague. The sculpture Glory Hole [2025], inspired by the clubbing scene and Pesellino’s St Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata, which he painted on a predella that’s now in the Louvre, turns the space into a kind of Postmodern sanctuary. Then there’s Julius Eastman [1940-1990], a gay Black composer who lived and worked in New York in the 1970s and 80s. In our Glyphs monotype series, we printed fragments of his musical notations onto images of our dancers.

Ryan Kelly: Eastman was a dancer and singer, but he also wrote classical music. Our monotype series combines images from our performances, glyphs, and gold leaf. The glyphs come from the score of Gay Guerilla, which he wrote to commemorate the Stonewall riots ten years earlier. He also did jazz concerts and a disco album. He was undefinable. These are the types of people who interest us – free, fluid beings who refuse to be reduced to an identity.

“Both of us were born during the AIDS epidemic. Our subjectivity was shaped by death.” – Brennan Gerard.

B.G.: Through this exhibition, we’re trying to explore these individuals’ subjectivity in all its complexity without limiting them to a single identity. In a certain way, we see them as gods. Both of us were born during the AIDS epidemic. Our subjectivity was shaped by death. And our work is strongly influenced by artists like Félix González-Torres [who died of AIDS in 1996]. The same question keeps coming up: “What should we do with our dead?” Moreover, I often link the question of death to sexuality…

R.K.: Probably because we both grew up in very Catholic families.

Is sexuality linked to questions of sin and guilt? B.G.: Yes, it’s an idea that can be found in the stigmata of St Francis. The queer movement has taught us to turn stigmas into pleasure and power. To use insults to empower ourselves. Stigmas also give us access to the Bardo, to a strength that lies elsewhere.

R.K.: And to an experience of transcendence that is dangerous and disturbing. Like a bad trip.

B.G.:Yes, the Bardo is very disturbing. In Tibet, it causes hallucinations. Like a nightmare that never ends.

“There’s a memento mori in the world of disco too. It’s a kind of liminal temporality.” – Brennan Gerard.

You use disco in your work, a type of music in which joyful, energetic beats are sometimes paired with profoundly sad lyrics. R.K.: It’s somewhere between mourning and militancy. For me, clubs are a place for mixing. You set your identity aside and immerse yourself in the community. With disco, it’s not just about my rights or your rights, it’s about embracing collective freedom.

That makes me think of medieval danses macabres, those wild celebrations of life during periods of crisis, like a memento mori… B.G.: There’s a memento mori in the world of disco too. It’s a kind of liminal temporality. Your body becomes a machine. You dance to the point of exhaustion. The beat itself comes from the machine. Everything is at the very edge of life, at the limit of something, to the point of transcendence. The Bardo and the club scene go together. The Bardo is the moment when the body becomes something else. I think that when you’re on the dance floor, there’s the same idea that your body and your identity undergo the experience of becoming something else. There’s a similarity between these two space-times.

Presumably in your work, as in González-Torres’s, the body is highly political? This dissolution of the body in the Bardo or on the disco floor is also a form of empowerment. B.G.: In our performances, we work with the very precarious body. Even if it is very tangible. We work on this dialectic between a highly tangible and transcendent figure.

R.K.: This is another reason why St Francis interests us. He’s also associated with this concept of precarity.

You created a filmed performance within Tadao Ando’s architecture at the Bourse de Commerce. Architecture is also a recurring theme in your work, as in your E-1027 video. R.K.: Architecture is a kind of vehicle for us. Originally, it was a way for us to meet, to have a space to share and live in together when we were a couple. So we started studying architectural designs, looking at the modern era and Modernist houses built with the awareness that it was necessary to create specific relationships between men and women in society. More modern, more egalitarian, more connected with nature. The majority of these attempts failed, or succeeded only for a time. Our approach is ultimately about testing how to live in a place…

What connection do you make between Eileen Gray and the E-1027 villa? B.G.: The film is a work of speculative fiction. We follow Gray on her last day and night in the house. She left it never to return. At the end of the film, Eileen burns all her papers and then leaves. This raises the question of letting go. Should we burn it all? For me, there’s something of a spiritual quest here, like the Bardo.

R.K.: Like a way of disappearing. It’s in this that we identify Eileen Gray with queerness, even if, once again, it’s speculative. Queerness that isn’t in the positive representation of an identity or way of life, but rather in the radical idea that we can go against the very idea of identity. At any moment, we can abandon our identity and attachments. That’s the queer project we’re committed to. The concept of queer as it emerged in the 90s was a place of liberation – against nation, gender, essentialisation, and for the destruction of the class system.

B.G.: Dissolution is a very powerful thing to pursue. It isn’t the end of existence. Practicing dissolution during your life without waiting for death. Or, in a way, how to die better.