17

17

Who is Anhar Salem, winner of the 2025 Reiffers Art Initiatives Prize?

On Tuesday, April 15th, the Reiffers Art Initiatives endowment fund awarded artist Anhar Salem its annual prize, which celebrates a young talent from the contemporary art scene. Her work is currently on display until May 10th in the exhibition “1000 milliards d’images”, alongside that of the other finalists.

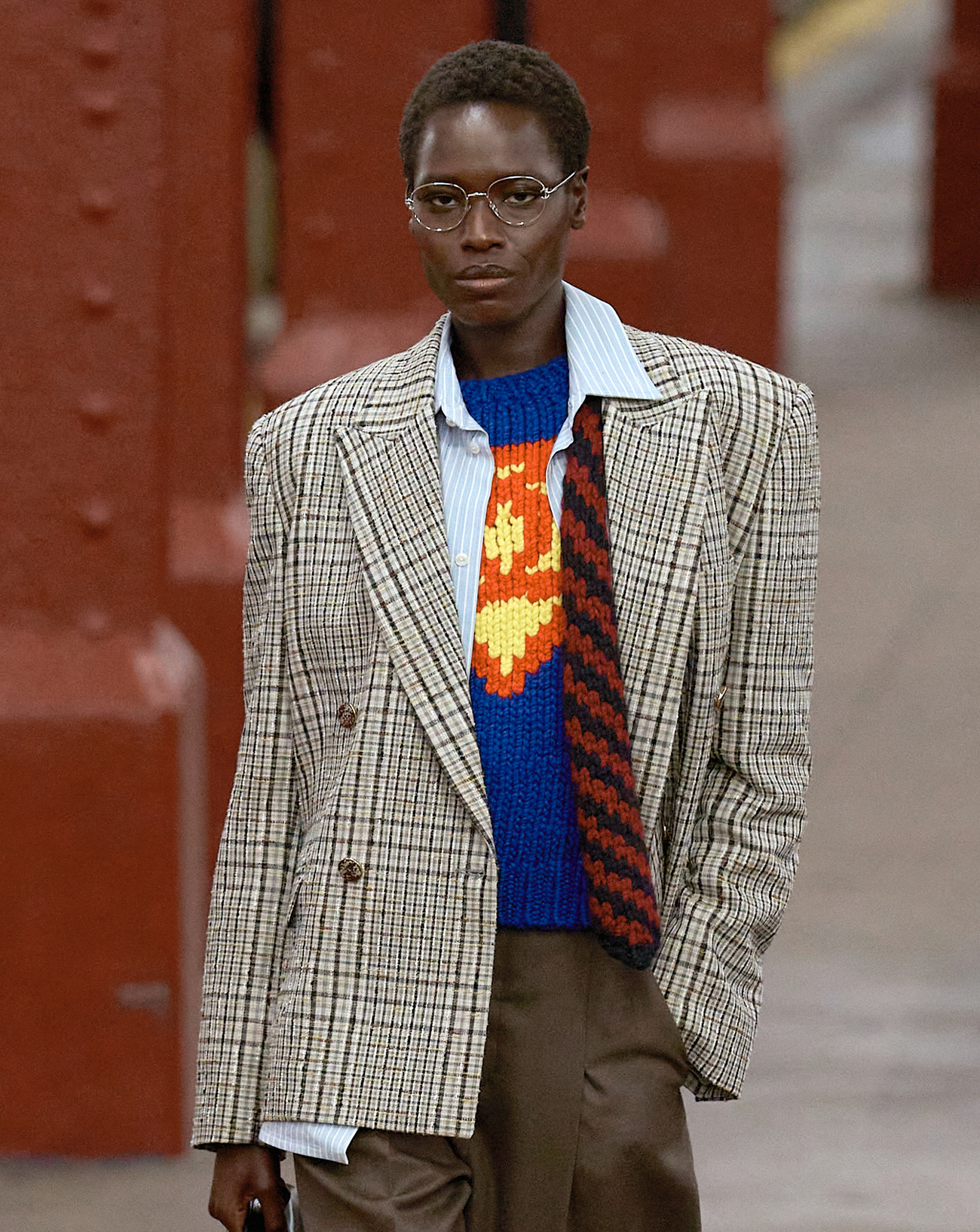

Portrait by Jonathan Llense,

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok.

Published on 17 April 2025. Updated on 30 July 2025.

Anhar Salem wins the 2025 Reiffers Art Initiatives prize

Since 2022, the Reiffers Art Initiatives fund has awarded a prize each year to a promising young artist selected by its artistic committee. The winner receives a €10,000 grant and a commissioned piece that will become part of the fund’s collection.

Following in the footsteps of previous recipients Pol Taburet, Ser Serpas, and Clédia Fourniau, this year Anhar Salem has been recognized for the powerful relevance of her video work, which explores the perils of image proliferation in the digital age and the new dynamics of power and alienation it generates.

Interview with artist Anhar Salem

Numéro art:The exhibition opens with a new, very personal video. What’s it about? Anhar Salem: I shot it in my bedroom with my iPhone during what you might describe as a psychotic or manic episode. At the time, I was becoming aware of my body and its reality.

You shot yourself in the same way the younger generation has become accustomed to filming itself, with your phone camera, as though making a Snapchat or TikTok video. This isn’t the first time you’ve shown an interest in how social media influence the way we portray ourselves. Yes, what interests me is precisely the idea of the accessibility of this technology that allows us to represent ourselves, like the cameras on iPhones. I filmed myself for half an hour during the manic episode, though the final video only lasts a few minutes. It was a moment when I was able to think about the strangeness of the reality we live in, a world where images overwhelm us and individualism is exacerbated. I spent that half an hour contemplating this state of reality.

But the video we see has been altered. You appear as a digital avatar… Actually, I used artificial intelligence to rework the video. My use of AI is very basic – I use prompts just like anyone does today. I find this interesting because it gives the video a very AI look, an aesthetic that is easy to recognize and that is often imposed on us. But this aesthetic didn’t develop in a vacuum, it’s the result of choices made by AI firms. AI is actually a product of mass media reproduction. It’s not intelligent – it reproduces what it’s trained to reproduce. So it all depends on the decisions made by the companies that create it.

“AI reproduces what it’s trained to reproduce. So it all depends on the decisions made by the companies that create it” – Anhar Salem

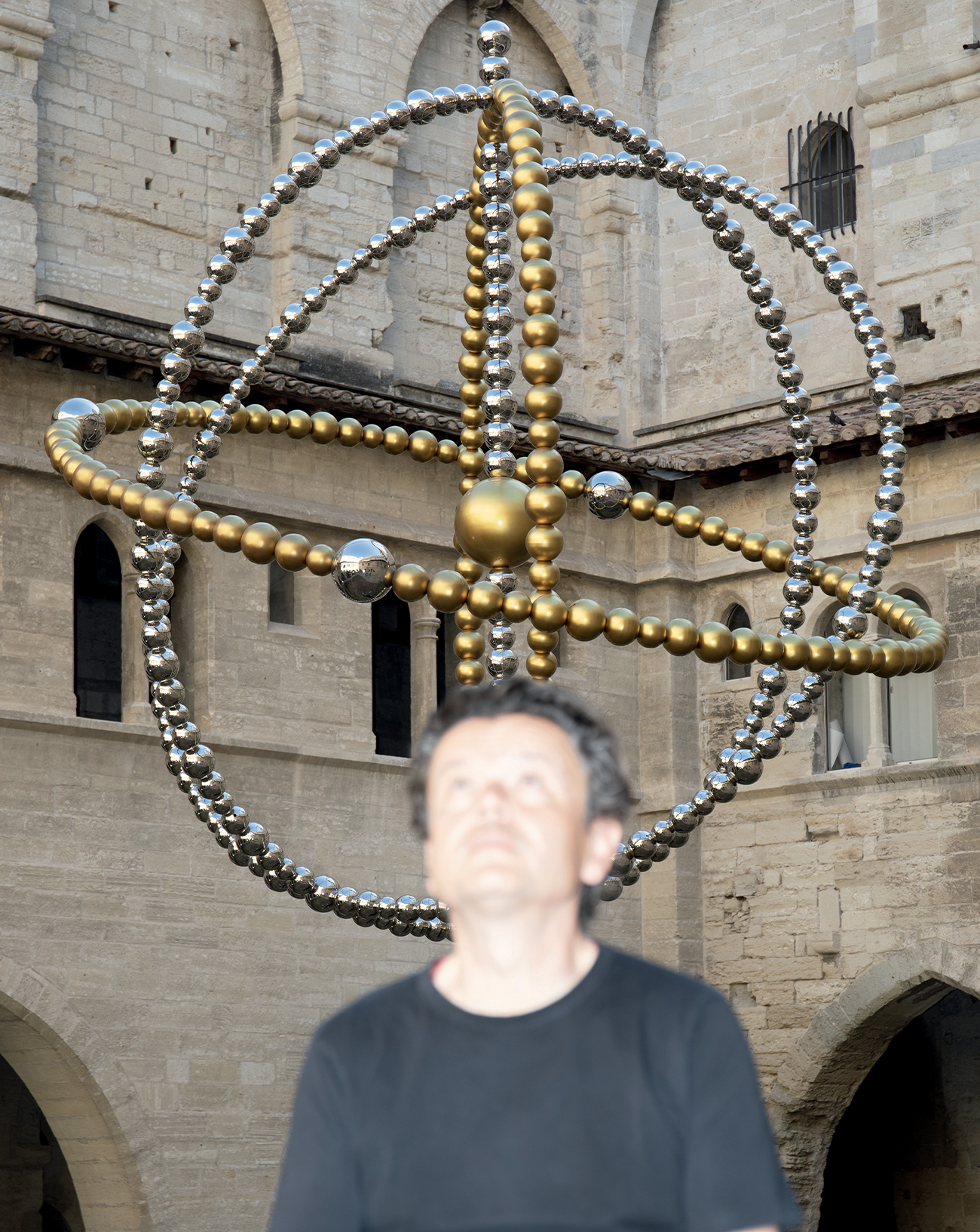

The video installation that closes the exhibition is made up of different parts: wallpaper covering the entire backdrop, a video placed inside it, and a sculpture at the rear with a poem that we hear from time to time. What is this piece about? With this one, I’m playing on the verticality of images available in new media, in particular social networks such as TikTok or Instagram. We’ve become accustomed to scrolling through images vertically. The video is made up from material found on social media and the Internet, with images that scroll vertically and give the impression they’re flowing like water from a fountain [Salem has superimposed a torrent of water on the video that seems to carry the clips along in a ceaseless flow].

Seen from a distance, the wallpaper evokes something divine, a religious building, but on closer inspection it turns out to be made up of hundreds of images of tech company logos and headquarters. I don’t mean to suggest that tech companies are today’s new religion, that would be a little too simplistic. These images are like pixels, they form a bigger picture, referencing the way these tech companies represent themselves to the public – their logo might include a blue sky, or their premises are shown next to gardens or parks… In other words, a world away from the reality of their activities.

Another feature of these companies is that they put their technology at the service of war and the military. I’m more interested in the way they create narratives and forms of representation, how they present themselves as a paradise or perfect world. And I draw a parallel with the way all religions do the same thing, as well as with the military, which forms a third institution with its own representations and narratives.

These narratives, whose image forms you’ve found online, condition our perception of the world. They flood us with representations and imaginaries. Yes, each in its own way shows us a paradise. But what exactly is paradise in our lives? In fact, this piece is less concerned with religion or tech companies than with the way in which the powerful define modes of representation and narratives and impose them on us… Yes, absolutely.