18

18

How Meriem Bennani became one of the most fascinating artists of her generation

In her shape-shifting practice of videos, installations, and immersive environments, the new york based artist wittily and ironically interweaves globalized popular culture and the ubiquity of digital technologies with the vernacular of her native Morocco.

Published on 18 May 2023. Updated on 3 December 2024.

Meriem Bennani, the artist who went viral during the lockdown

It was March 2020. Like the rest of the world, I was locked down at home. Scrolling through Instagram, I came across Meriem Bennani’s account. She had just posted a video, made with fellow artist Orian Barki, that would prove hugely significant in this period of planetary anxiety. In the first episode of the animation 2 Lizards, the anthropomorphic reptiles of the title – one green, voiced by Bennani, the other brown and voiced by Barki – stand on a Brooklyn rooftop at sunset discussing their first week of shelter in place. In the background, a Miles Davis-style serenade is played by the neighbours: on a roof across the way, we see a horse on the trumpet, a bear responds with keyboard and sub-woofers, while a sheep joins them on the double bass.

2 Lizards: a successful series during the pandemic

2 Lizards paints a surreal portrait of the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, highlighting the helplessness and uncertainty as well as the unexpected moments of shared community. With dialogues that brilliantly reflect the anxiety, boredom, and absurdity of lockdown, Bennani and Barki’s lizards became an instant Instagram hit. Encouraged by the success of this first episode, they went on to create seven more, posting them on Bennani’s feed between March and July 2020.

Using video fiction to convey committed messages

Bennani’s practice generates its own universe and vocabulary, combining her personal imagination with an aesthetic inherited from a rich lineage of cartoons – spanning the entire range from the experimental to Disney – and using sophisticated post-production techniques and technologies. Often deployed to comic effect, the 2D and 3D ani- mations (created with software such as After Effects or Cinema 4D) are complemented by audio tracks either specially composed or found on the web. Bennani’s work is often read as a diasporic critique of the internalized effects of post-colonialism on its subjects. Such was the case, for example, with her installation Mission Teens, shown at Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2019, which follows a group of teenagers from the French lycée in Rabat, where the artist herself studied.

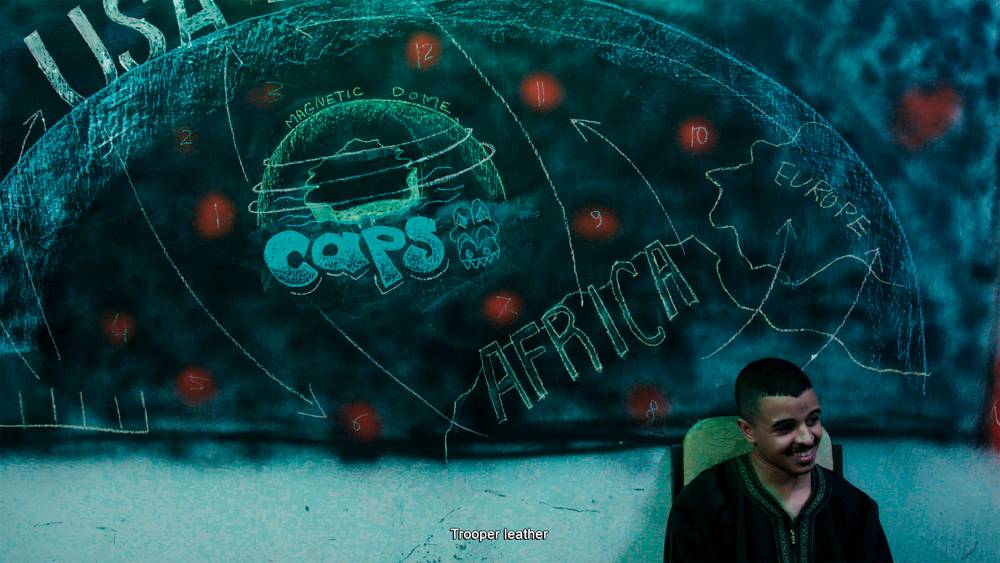

Dystopian and supernatural tales tinged with humour

Her film trilogy Life on the CAPS (2018–22) again explores complex political conflicts, detail- ing the intuitive life aspirations of those involved, but without attempting to provide a clear resolution. It takes place in a dystopian supernatural future on CAPS, a fictional island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, at a time when air travel has been replaced by teleportation. Illegal migrants to the US are intercepted and redirected to CAPS, where they live in an endless limbo. Layering live action footage and computer generated animation, Bennani intuitively adapts editing techniques that evoke documentaries, science fiction, phone footage, music videos, and reality TV. Moving fluidly from the imaginary to the geopolitical, the microscopic scale of DNA to the eye of global surveillance, the power of individual experience to the collective consciousness, Life on the CAPS draws on emotive and formal experimentations that refuse all boundaries.

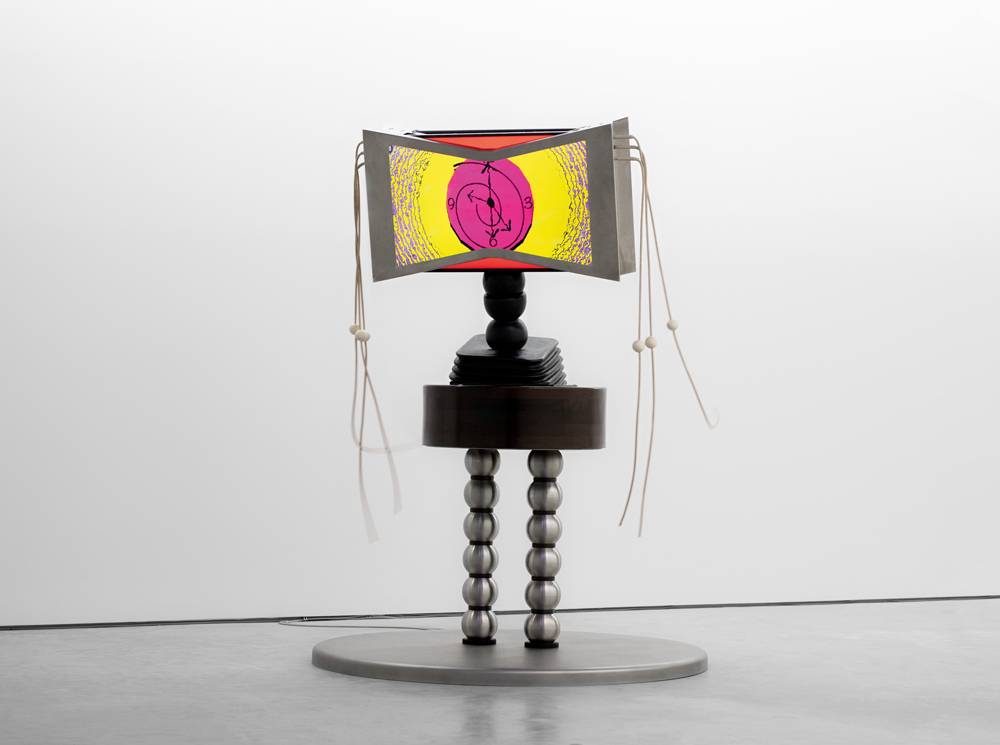

An art of subversion, presented from the Whitney Museum to the Clearing Gallery

In her installations, Bennani pays particular attention to the subversion of architecture and everyday objects in a persistent gesture of distancing and self-derision. Whether featuring low-slung red-velvet couches, as in FLY, shown at PS1 in 2016, or psychedelic objects, such as the apple-green and strawberry-pink hair-salon driers and mas- sage chairs made for her Art Dubai commission and shown at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, her works recall the interiors of the Maghreb or the beauty salons, amusement parks, and shopping malls of the Arabian Gulf. Moreover, Bennani seeks to exhibit her work in multi-sensory environments rather than on a single monitor or screen, exploring the new models of media consumption that have developed with smartphones and other portable devices.

At the Whitney, she incorporated moving images into a large-scale installation that she called a “video viewing garden,” an environ- ment of futuristic planters and seating. On New York’s High Line last year, she created Windy, a kinetic sculpture re- sembling a tornado in constant motion that references both cartoon twisters and the fast pace of New York life. And for her exhibition last autumn at Brussels’s Clearing gallery, Bennani subverted and motorized a series of everyday objects, such as a seat fitted with a straw parasol pierced like a cheese and sporting broom-shaped legs, or a salad centrifuge that spins both lettuce leaves and socks.

If Bennani has been hailed as one of the most fascinating artists of her generation, it is precisely because of her ability to deconstruct the dichotomies between the West and the global South, and between the public and the private, as well as her skill in unveiling the complexities of cultural production, of artistic disciplines, and of diverse identities. In a globalized world that is increasingly conflicted by the identity politics engendered by late capitalism – and in an artistic community that is often divided by them – Bennani’s deep and generous approach appeals to the infinite hope (or perhaps the crazy utopia) that what we have in common might one day surpass what separates us.

Meriem Bennani is represented by the Clearing gallery in Brussels.