4

4

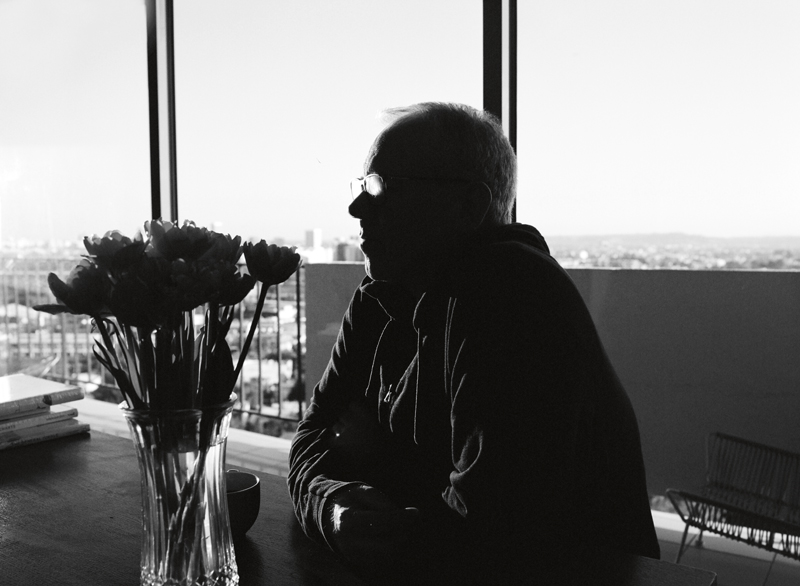

Interview with Bret Easton Ellis : “ I think I was too afraid to talk about how much ‘American Psycho’ was about me.”

As a major novelist of the fin de siècle, he described like no other the alienating emptiness of our violent, pleasure-seeking, lucre-obsessed times. Continuing to observe the world from his base in L.A., he’s about to publish his first essay, White, an analysis of privilege, neutrality and freedom of expression.

Interview by Philip Utz,

Portraits by David Black.

Published on 4 September 2020. Updated on 20 June 2024.

Numéro: Are you more of a happy or a sad person?

Bret Easton Ellis: I think I’ve always been more of a melancholic person, perhaps. Always a bit of an optimist. I think you have to be somewhat optimistic in order to write fiction. You can be sad about the state of the world, but writing fiction is an active thing, it’s not passive. So you’re actually doing something, and in order to do something, I think you have to be… I don’t know if happy is the right word, and I don’t know that I can break the world down into “happy” and “sad”… I would definitely say I’m not a sad person. But on the other hand, can I really say that being human is a happy experience? I just don’t know.

Does writing help? Is it a means towards happiness?

It is, because it takes you out of yourself, you’re getting something done, you’re creating something, and you forget about the world. I also feel a sense of accomplishment when I’ve written something, even if it’s just my podcast or answering emails. So all day long I’m writing, which is something I’m compelled to do. It helps ground me.

“By the time it’s published, you actively dislike the book. And then you have to go out and promote it.”

When writing a novel, when do you feel that sense of accomplishment? When you’ve written the last sentence? Or when the book becomes a bestseller?

The novels usually take a long time to write – up to eight years sometimes – and I don’t think I’m going to spend that much time on a book ever again. If I do write another novel, I’m going to do it very quickly, and enjoy myself, and not think it out too much. But I do think that, because my novels always took such a long time, there were stages. I worked on the first section of Glamorama for two years. And when I got to that final section, I thought: “Great!” Many people say I should have stopped there, but I decided to go on for another five sections. So the accomplishment comes in gradations. But yes, there’s also always a massive sense of accomplishment when you write that last sentence. When I finished Glamorama, after eight years, I was by myself in my apartment, with all my notes scattered around me, and I was crossing things off, and typing a couple of sentences, and looking at the clock because I knew I had to meet friends for dinner at 7.30, and then I typed, “The mountain looks like the future,” and realized, “Oh, I’m done! I’m done with the book!” And that’s when I felt a wave of release wash over me.

“My boyfriend thinks I’m rich, but he doesn’t know my tax situation and doesn’t realize it’s all a big mess”

Do you suffer from baby blues after finishing a novel?

That’s a good question. I actually don’t – I’ve never had any kind of post-partum depression. What does happen though – after finishing but before publication – is that you go over the whole thing many, many times, with your editor, with copy editors, and you become sick of it. And by the time it’s published, you actively dislike the book. You don’t trust it. And then you have to go out and promote it. It’s a very strange situation.

How much attention do you pay to reviews, critics and sales?

I honestly don’t care how many books I’ve sold – I never ask, sometimes I find out – because I feel like it’s not something I can control, so I’m not interested. I can’t control the critics either, but I do read my reviews. I’ve gotten used to bad reviews, because I received terrible reviews for the first book I published, Less Than Zero. People don’t remember this, but I was there, I read all the reviews, and they were 50% negative and 50% positive. Many reviewers were shocked that a publishing company would let this young teenage drug addict publish his diaries. They thought it was a new low for American publishing. So I got used to scathing reviews at a young age, and then of course, in America, all of the reviews for American Psycho were goddamn awful, and again they chastised the publisher. Even if I’m less interested in them now, I’ll still probably read most reviews that come my way.

“The very first step is a feeling, usually one of confusion or pain.”

How do you become rich as a writer? How many books must one sell to become a millionaire?

I certainly haven’t sold enough to become a millionaire. I haven’t earned out most of my novels, in the sense that they haven’t paid back the advance. You don’t make $1 million when you’re a writer, that’s why I moved to Hollywood, where you can at least get paid for the television pilots and screenplays you write. Books were never something that would make you rich. I’ve been able to make a living as a writer, but always with stress about money, scraping by from pay cheque to pay cheque. Whenever I complain about money to my boyfriend, who’s a millennial and a dem- ocratic socialist – I think he’s actually a communist –, and say, “How am I going to pay the mortgage?”, he’s disgusted. He thinks I’m rich, but he doesn’t know my tax situation and doesn’t realize it’s all a big mess.

Don’t the film adaptions – Less Than Zero, or American Psycho, for instance – come with a big pay cheque?

The big pay cheque for American Psycho was that the production company optioned the book, meaning that they don’t buy it, but they give you a little bit of money so that they can control the rights. And they kept optioning the book every year, so that was a money flow coming in for a few years. And then, of course, when they finally buy the book to adapt it to film, then yes, you do get a bit of money. But then again, American Psycho was never a number-one bestseller, and didn’t have a lot of people trying to adapt it, just the one production company. So, basically, I had to accept their offer. And believe me, it wasn’t that high. I was like: “Okay, I’ll take the money, they’ll never make this book into a movie, and let’s just be done with it.” And then things turned out differently. So in many ways it was a bad deal for me, even though it seemed like a good one at the time.

“But ultimately, I think I was too afraid to talk about how much American Psycho was about me.”

Once you’ve sold the book, to what extent can you intervene on the movie adaptation?

It depends on the production company, and it depends on the writer. E.L. James, with Fifty Shades of Grey, was granted total control over the film franchise that was spun out of her novels. I’ve done it a couple of times, I did it recently on a small horror movie that was based on a script of mine, and that I also produced. I had a say in the casting, and the choice of cinematographer. But every deal is different, and most of the time I haven’t had a say on any of the movies that were adapted from my books.

You mentioned your millennial boyfriend. Do millennials actually read books?

No, not really. Well, maybe they read books, but I don’t know that they write books. I’ve been waiting for the great millennial novel, and it hasn’t happened. Which kind of suggests something to me. I mean, they’ve been around for over a decade, and they’ve already all hit their 30s. I have a feeling it’s because they don’t read – my boyfriend will only read very occasionally, maybe one or two books a year, but I feel that it isn’t really a thing for him, unlike it is for me. I was raised in an era where novels were items – I would carry a paperback around with me all the time – and that’s where I would get my information about the world, that’s where I learned about other cultures, through novels. So I was trained, in a way, to read them, and I still do. I have two or three going right now. Reading gives me a lot of pleasure. However, I don’t think it gives my boyfriend the same kind of pleasure as when he’s playing a long-form video game with many characters and a very complicated narrative. That’s what he does in the morning, while I go back to the bedroom and open up another book. I’m not saying that in a superior way, it’s just the way of the world.

How has the way people consume literature changed since your first novel came out in 1985?

Everyone that I know still buys hard-covers or paperbacks, and sales of Kindle and eBooks have kind of flattened out. So there seems to be a ceiling on people wanting to read that way. I think people like the objects. Personally, I like to hold a book, I like to look at a book, and I like to turn pages, actual analogue pages. I think that part of the difference is that TV has replaced books for a lot of peo- ple. I know people who used to read a lot, and who are now talking about a ten-episode miniseries. Television seems to have replaced the pleasures of reading long-form fiction. Even for me, that’s apparent. If I get caught up in a TV show, I’ll often find myself watching it in the morning instead of reading a book. I’ve also noticed that reading for more than 45 minutes has become almost impossible. I don’t know whether that’s a sign of the times, or just age; it takes more out ofmenowthanitdidwhenIwas younger and I read a book every day.

How has social media influenced the way you write, if at all?

That’s a good question. I don’t think it has. I think my style and approach pretty much came together and were set in stone way before social media happened. I’m talking about when I was a teenager and in my early 20s. That was pretty much it for me. I don’t think my style is ever going to change due to the upheavals in technology or whatever. I mean, I started writing books on a typewriter, and yet moving into computers really didn’t alter the way I wrote. The only thing it might have done – and I caught myself on this – is that being on a computer allowed me to go on too long sometimes.

When you say that working on a computer made you “go on too long”, is that why Glamorama took eight years to finish?

Well, that was the first book I wrote on a computer, but that was always going to be a long book, and ultimately the style and the character’s voice dictated it, and the computer had nothing to do with it. When I said “go on too long,” I don’t know that that was for my fiction necessarily, which is very pre-planned: in advance of the actual writing I do a massive outline, and experiments with the characters’ voices, etc. I was talking more about writing emails and arti- cles and stuff like that.

What are the different stages of writing a novel?

The very first step is a feeling, usually one of confusion or pain. And then I ask myself, “Why am I feeling this way?” Less Than Zero had to with the fact that I was living in New York, American Psycho stemmed from my figuring out why I was still so angry with my father… Being in love in college, dealing with celebrity, all of these things usually form the basis of a novel. And then I start to make notes, and after that I start to think, “Is this really a novel?”, and then a character emerges, a narrator emerges who’s a metaphor for everything I’m thinking, and then it kind of leads on from there. I do an outline, and based on that outline I schedule out how long it will take, and then I begin writing.

So the narrator that emerges is essentially an avatar of yourself?

It always has been, with all six novels. In a weird way, they’re like my biography.

Didn’t you once claim that the Patrick Bateman character in American Psycho was based on your abusive father?

Well, I think in a way it was about him as a hip, young businessman in his 20s. Which is what he was: he worked for a real-estate company and he wasn’t happy. I do think there was a lot of that that I poured into Patrick Bateman. But ultimately, I think I was too afraid to talk about how much that book was about me. It wasn’t until ten years ago, during the Imperial Bedrooms book tour, that I was finally able to say, “Look, this was a very autobiographical novel, and it was really about my youthful despair in New York during the Reagan 80s and the years of the yuppie.”

I remember reading an epic story in The New York Times a few years ago entitled Here is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie. Were you on set for The Canyons, which you wrote the screenplay for in 2013?

Yes, for a couple of days. It was such a small crew, just me and [director] Paul Schrader. I trusted him, I wrote the script for him, we made it very fast, and it was a wonderful experi- ence. That article makes it seem like a train wreck, which it really wasn’t. Lindsay was late a couple of times, and she had her own issues, but it was a great experience, and both Paul and I were very happy with how the film came out.

“Every reporter likes to ask about the #MeToo movement, because they want you to fall into a giant pit and totally fuck yourself up.”

Is there such a thing as a nightlife in Los Angeles?

Whenever I’m here I get the impression everyone’s in bed at 9.00 pm, that I’m all dressed up with nowhere to go. You’re correct. I don’t think there are any restaurants here that are really open after 10.00 pm. I’m certainly in bed by then. I’m sure there is a nightlife, and I know that there is a surge in nightlife because of Uber, which has pumped up the profits in many bars and lounges, because people will drink more. But I’m too old for all that stuff, I can’t even go to a screen- ing or a cocktail party. I can meet friends for dinner, but that’s about it. And it has to be around 7.30 pm. But L.A. has always been that way, because of course it’s tied in to the TV and movie business, and filming and production typically start at 6.00 am.

Isn’t Los Angeles slightly isolating in that sense?

Completely. I experienced the isolation of L.A. when I moved back here from New York. I felt it a little bit as a teenager, but didn’t fully feel it till I moved back as an adult and was living on my own here. That first night, alone in my condo, I couldn’t believe the sense of isolation I felt. There was no sound, the city was far away, un- like New York, where my apartment was on the street – there I could hear cars all the time, people talking on the sidewalk, fire engines… I could hop out of my apartment, jog down to the deli and maybe even run into one or two people I knew. But you know what? I like it here now. It took some readjustment, but I vastly prefer living in L.A. than in New York.

Why did you decide to move back to Los Angeles in the first place?

I’d been spending a lot of time in L.A. anyway, since 2003, and I actually lived here all through 2004 and into 2005 when I was finishing up Lunar Park. I went back to New York for a few months and that’s when I realized that the party was over. I’d had a great run there for two decades, and it was awesome, but then the party ends, and it ends at different times for different people. I had a partner [the sculptor Michael Wade Kaplan] who died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage, and I’d been with him for seven years, and that ghost was lingering around, which was also part of the reason I decided to leave and reinvent myself in Los Angeles.

What’s your take on the #MeToo movement?

You know, this is the question that every reporter likes to ask, because they want you to fall into a giant pit and totally fuck yourself up. I mean, honestly! I had someone ask me that question yesterday, and I completely avoided it, because you just can’t win. You criticize it and you’re hung out to dry as a rampant misogynist, you say, “I’m all for it,” but when it’s weaponized it isn’t cool. So all I can say is that it’s intentions are good. And, well, yeah.

White, by Bret Easton Ellis (Penguin Random House), out on 16 April.