16

16

Who is Peter Hujar, photographer of the intimacy overshadowed by Mapplethorpe?

The American photographer, who died of AIDS-related illness in1987, never enjoyed the recognition he deserved. Paris’ Jeu de paume is celebrating his very special talent.

By Patrick Remy.

It took over three decades for Peter Hujar’s work to be recognized for its true worth, a process that began in 2017, on the 30th anniversary of his death, when publishing house Aperture brought out the monograph Peter Hujar: Speed of Life. This first step in his rehabiliation had been orchestrated by the Pace/MacGill gallery in New York and the Fraenkel gallery in San Francisco, alongside his executor, the writer Stephen Koch. During his lifetime, Hujar did not have an official gallery and published only one book, the masterpiece Portraits of Life and Death (1976), which was prefaced by Susan Sontag, whom he had befriended in 1963.

Hujar’s life began in Trenton, New Jersey, where he was raised by his Ukrainian grandparents: his mother lived in Manhattan, where she worked as a waitress; his father had left long before he was born. At the age of 11, on his grandmother’s death, he went to live with his alcoholic mother and her partner, both of whom dished out copious violence. A gin bottle thrown against the wall was the final straw, and he left home for good at 16. This unloved adolescent would constantly seek the company of those like him, such as the artist-activist David Wojnarowicz, who was briefly his boyfriend. His interest in photography came from leafing through fashion magazines like Harper’s Bazaar, and especially his discovery of Lisette Model (1901–83), a European photographer who showed a disturbing vision of America long before Robert Frank, and who had been a pioneer in her combination of street photography and fashion.

Hujar started out as an assistant to Otto Maya and Jess Brown, who shot for interior and lifestyle magazines, before taking night classes with Richard Avedon and the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, Marvin Israel. Right from the start, he knew he wanted to do portraits. Avedon wrote him, in 1979, “If there are new photos you want to sell, don’t hesitate to call, because I’m your collector.”

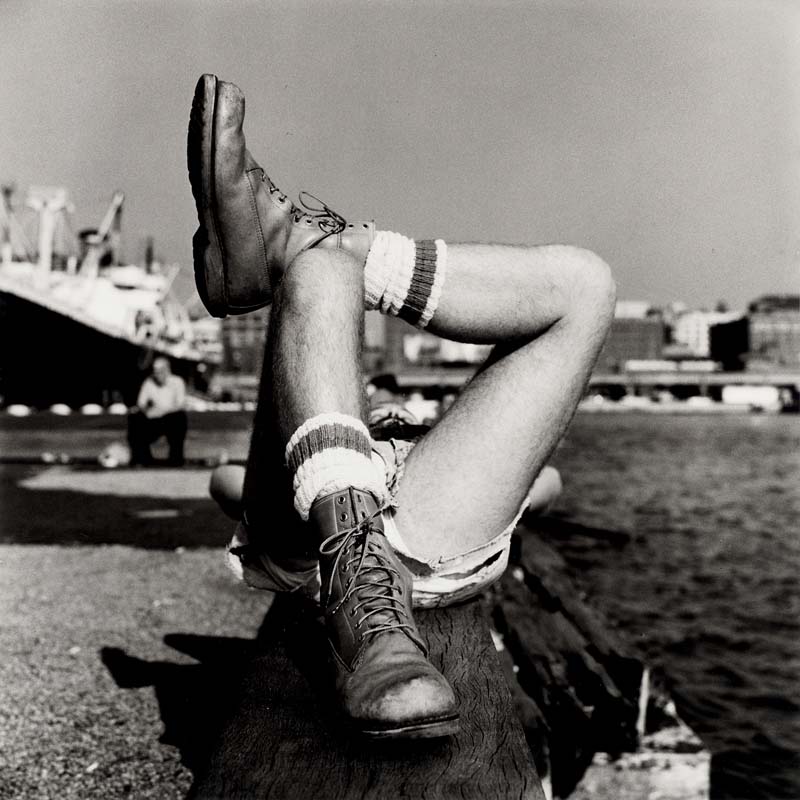

“He just about squeaked by from one month to the next, with not even a dollar to spare,” wrote Koch. “Yet he never seemed poor. He just never had any money. Tall, exceedingly handsome, calm, and upright, he seemed entirely sure of himself. But under that self-possession lurked something ominous, even dangerous.” He photographed the people around him, portraits being an act of love. He was one of the first to capture the nascent New York gay scene, when it was still taboo and invisible, despite a gradual awakening in the wake of Stonewall. It was at this point that he met the critic Vince Aletti, who at the time was freelancing for the underground radical fanzine Rat and moonlighting in bookstores. “So Downtown wasn’t exactly foreign territory for me, but Peter knew it more intimately, more intuitively than I did; he understood its rhythm, nuances, pleasures, and pitfalls. He went places I never dared to and hung out with people I’d only read about. He was charismatic and complicated and, it turned out, deeply insecure, with a damaging family history he kept mostly to himself,” Aletti would later recall.

Gay New York bohemia had a big appetite for the new: Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous (“We’ve gone beyond the absurd: our position is absolutely preposterous”),

the Cokettes (more theatrics, in hippie/drag-queen mode), John Waters’s film Pink Flamingos, the Filmore East concert hall, or clubs like Max’s Kansas City and the Tenth Floor, where disco reigned supreme. In this milieu, you rubbed shoulders with Susan Sontag, Fran Leibovitz, William Burroughs, Renaud Camus, John Cage, Kiki Smith, Quentin Crisp, Divine, Diana Vreeland, Iggy Pop, Merce Cunningham, Loulou de la Falaise, Cookie Mueller and, of course, Andy Warhol. A heady mix of the art world and high society, the fight for sexual difference was championed here. And they were all photographed by Hujar, including his lovers Wojnarowicz and Paul Theck, as well as drag queens Ethyl Eichelberger and the transgender artist Greer Lankton.

Little by little, he photographed his friends in their hospital beds, like Sydney Faulkner of Theater of the Ridiculous, the transgender actress Jackie Curtis and, of course, Candy Darling, one of Warhol’s superstars posing on her deathbed at New York’s Cabrini Medical Center. According to art critic Arthur Danto, who is usually stingy with compliments, it is one of the century’s most important photographs. Hujar’s camera was an instrument of seduction, a tool for playing in the space between intimacy and distance. Shoots would sometimes last hours. “The room was usually very quiet, except for the clicking of the camera,” says Koch. “He wasn’t very chatty. His eyes stayed fixed on you, steadily watching. He walked around. He might say, ‘This isn’t working, try a different position.’ You sensed that he was waiting – waiting for you to tire of being photographed, waiting for the flicker of something that the camera would snatch out of time and reveal as you and nobody else. Such moments come and go quickly. Peter often found them only in the contact sheets. In a portrait of Edwin Denby, the poet and dance critic, the subject’s eyes are closed in what seems an old man’s introspective serenity. In fact, Denby had merely blinked.”

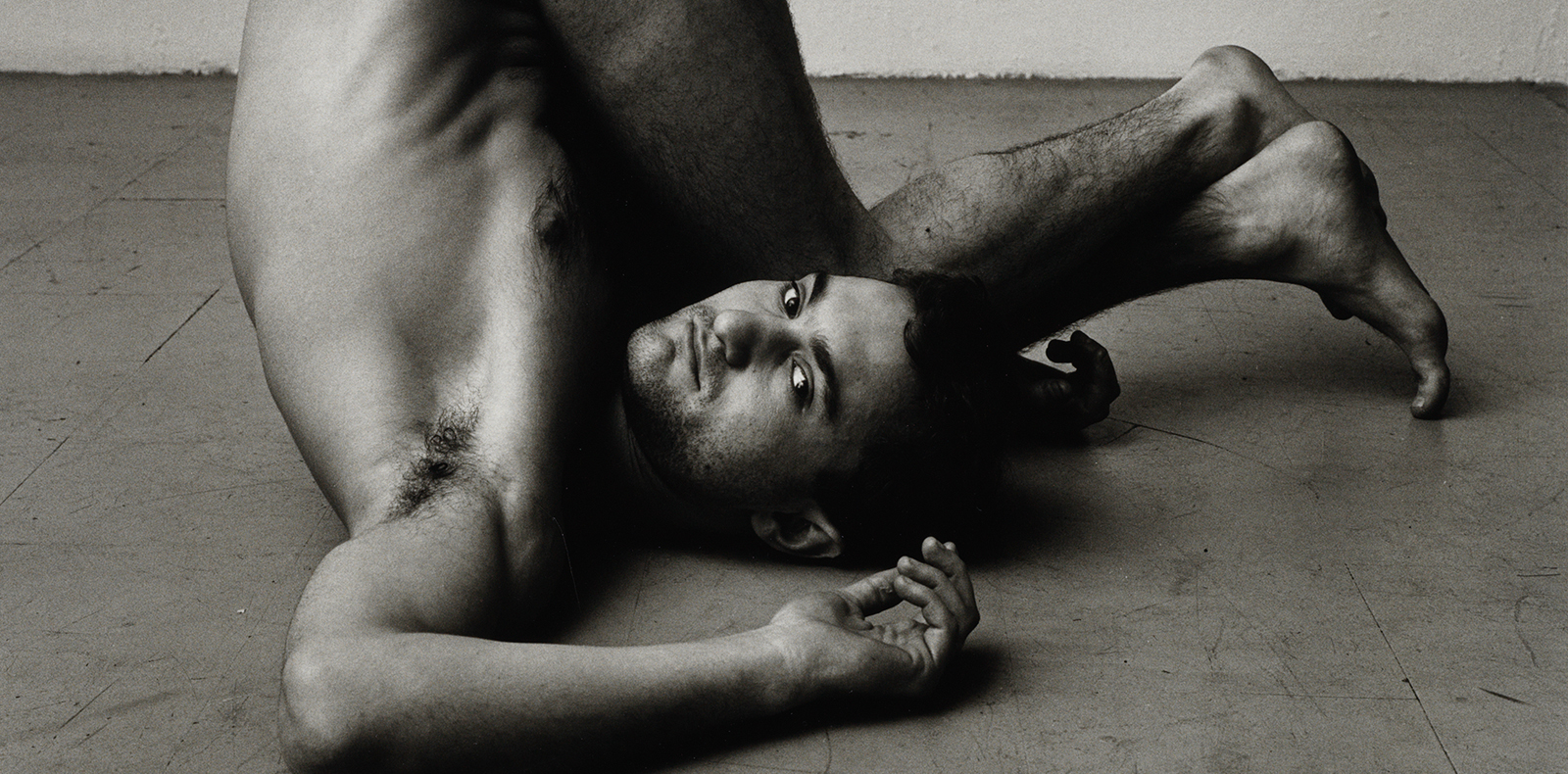

In addition to hospital beds, Hujar’s themes included happy children, sad clowns, crazy gay Hallowe’en parties, dogs, but also cows, horses, orgasmic men and nudes. “Peter had no formula,” Koch continues. “The special thing the camera saw had to be unique and your own. Anything less was, as he put it, ‘worthless.’ It could be graceful or awkward, pleasing or mortifying, candid or posed. It just had to be real, and it had to be beautiful, in his personal sense of those crucial words … Your portrait was always unmistakably you, but only because it was also unmistakably his. The intimacy was in his style.”

Hujar’s was a classic black-and-white technique using themes recurrent in art history; he looked for humanity, never treating his models, even the most eccentric, as freaks. He was not a studio photographer in the usual sense, because he would set up his studio in his subjects’ homes, sharing their intimacy. The Jeu de Paume is paying homage to a major artist, one who was long eclipsed by Robert Mapplethorpe – also gay, also a victim of AIDS, also a practitioner of classic black-and-white photography. But Mapplethorpe rarely left his studio, where Hujar was always out in the field; Mapplethorpe shot the end of bohemian gay New York, where Hujar captured its hedonistic beginnings.

Peter Hujar, Speed of Life, from October 15th 2019 to January 19th 2020, Jeu de paume, Paris.