2

2

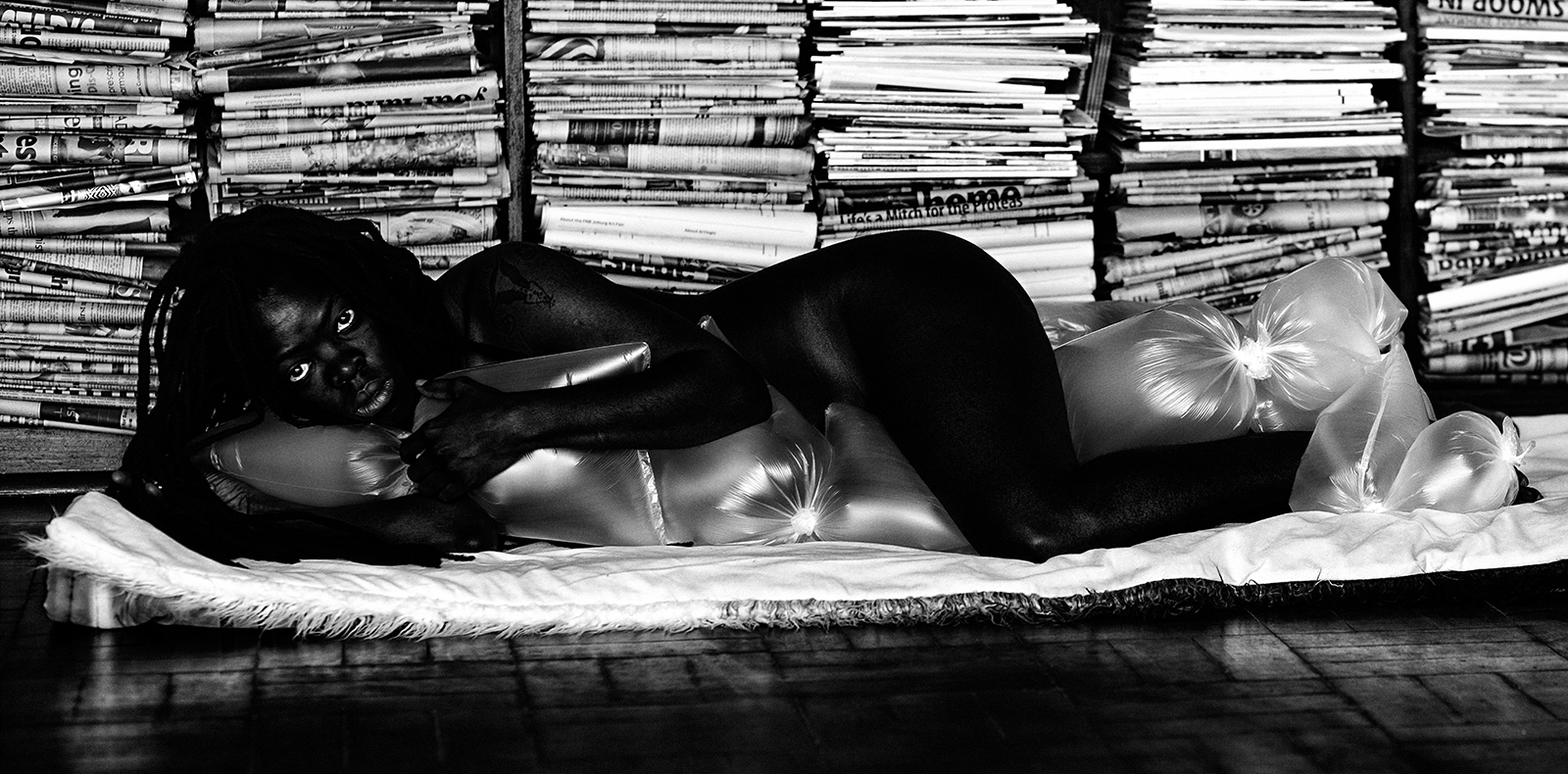

Visual activist Zanele Muholi dive into their first retrospective in Paris

After being shown at the Tate Modern, Gropius Bau and the National Gallery of Iceland, Zanele Muholi’s first ever retrospective lands in Paris, on view until May 21st at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie. The South African artist, who define themself as a “visual activist”, dive into twenty years of photographic and film practice whose main goal has been to show and celebrate Black queer people of their country.

Interview by Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 2 February 2023. Updated on 20 June 2024.

Numéro : Twenty years ago, you presented your very first solo show in Johannesburg. How were you feeling back then, when it opened to the public?

Zanele Muholi : At the beginning, showing what I did was very risky, not knowing whether the curators were willingly and in the capacity to showcase queer work like the one I was doing at that time. This was at a time where many hate crimes happened in South Africa and people wanted to use queer people’s presence as a scapegoat for their own failures. Internet was still not very accessible, so things were way more difficult as they are now. Today, when you need a community of people you are able to access it, and if you need a space to make people connect it is easy. Many queer people used to be reluctant to present themselves as they true selves. They thought: “What if I’m being outed, disowned, excommunicated from the church I go to or expelled from the school and classes I attend?”. It has been a very long journey to get to where we are now. Before my show, hhow many retrospectives at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie had as many Black LGBTQ+ subjects?

“Today, we cannot defend human rights without visuals.” – Zanele Muholi

Your retrospective has been a long time coming. It was prepared four years ago, before Covid, then was shown for the first time at the Tate Modern in 2020 before travelling to other cities in Europe. How has it evolved over the years?

Between London, Reykjavik, Copenhagen or Berlin, aside from its display adapting to the different exhibition spaces, what I noticed most is the ways visitors are experiencing this retrospective according to where they live. Some people are very excited to see that many Black people in a predominantly white setting, as we were non-existent there before. Or when there were indeed images of Black people, they usually were taken by white photographers. That is why it is crucial to encourage Black people to represent and support Black people. For too long, we gave been demonized and our stories distorted and misrepresented. Seeing ourselves in different spaces and reflected in artworks is the most positive way in which our stories could be captured.

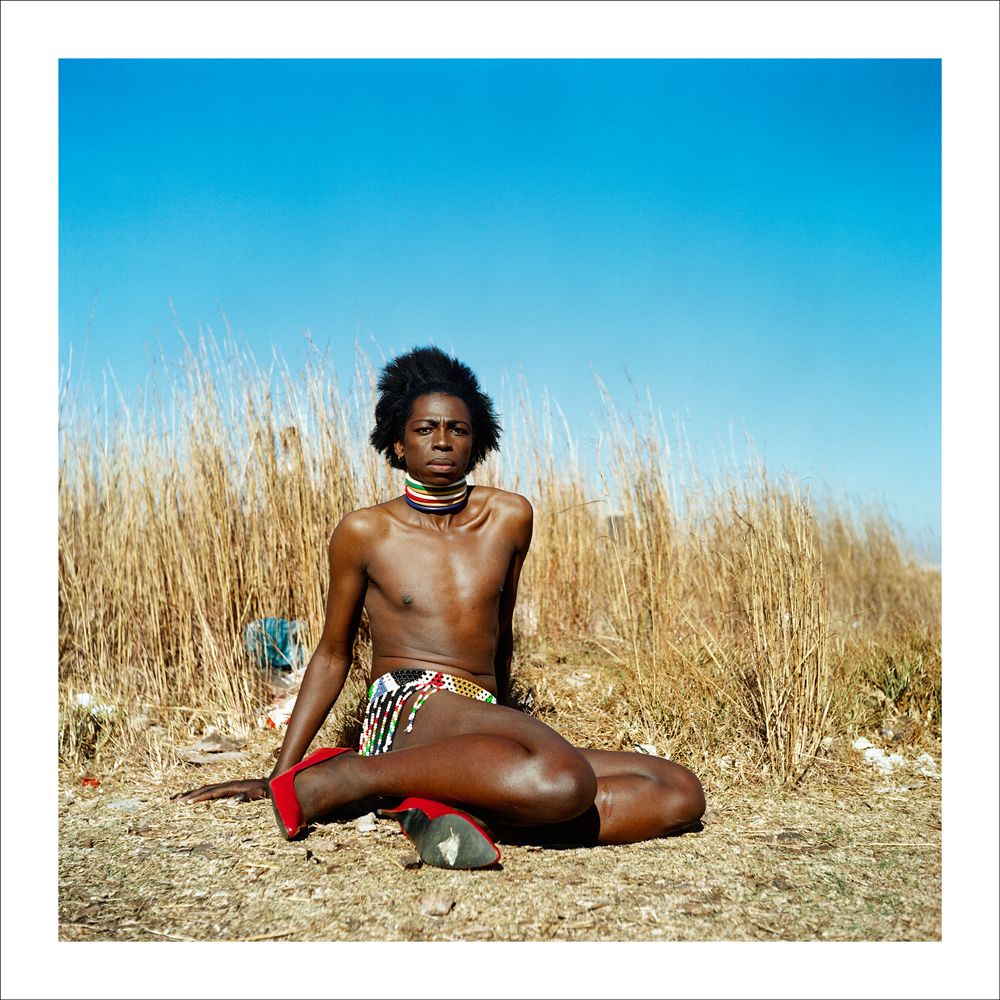

We enter the exhibition through one of your earliest series, Only Half the Picture (2002-2006), where naked Black lesbian bodies appear in sensual and erotic scenes. Their faces are turning from the camera or is cut from the frame. Then in the other room we see dozens of portraits from your series Faces and Phases, where many Black queer people are showing themselves frontally, embodying full power. Did you feel it was safer to make them that visible when you started it in 2006?

When I was in photography school between 2001 and 2003, I still photographed Black queer people, focusing more on their body. Because before you wear pink or violet, before you behave and you walk the way you do, your body is queer anyway. So this reality made my first images really difficult to show back then. Five years later, I started Faces and Phases when I lost a great friend, as a tribute to her. My nephew committed suicide the same year, and I lost another friend the following year. So I thought it was about time we became visible. We cannot be only relevant once we are dead, when somebody has been violated or became a victim of hate crime. Even though life is harsh out there, I want to remind people that we are still beautiful human beings who exist as much as other citizens of South Africa. We pay our taxes, we contribute to the economy of the state. The mainstream media often frames our identity without taking what we bring to our country into account, so I just wanted to reverse that. In Faces and Phases you have people who hold many different positions in society: you have artists, teachers, scientists. Let those positions become relevant as much as the issues that we face on a daily basis. We are more than what people project onto us.

“Silence is violence. Since making noise is equally dangerous as shutting up, us Black queer people have to maneuver that.” – Zanele Muholi

While walking around the show, we can feel the issues experienced by LGBTQ+ people, but what emerges the most is a feeling of celebration. Violence is not hidden in your works, but the show does not go too deep into tragic imagery or stories about suffering. Is that deliberate?

Silence is violence. Since making noise is equally dangerous as shutting up, us Black queer people have to maneuver that, negotiate our place in different spaces all the time. When I worked on the show, I had the choice to present myself in a desperate way or to present celebration, which I chose in the end. There’s a fine line between celebration and commemoration, as it is important to commemorate all those who have passed, to remember they will always be part of us. But we can also see ourselves growing old together, creating families within us, no matter the environment created by those who hate us. So why should we always have to go towards tragedy? Sometimes it is not necessary. The most important is to make sure we could be presented as we like. Owning our narratives is our responsibility.

In your Faces and Phases and Brave Beauties series, you have photographed more than 500 LGBTQ+ people all over South Africa. How do you choose them and make them feel comfortable in front of your camera?

I photograph people I find appealing most of all: it may be someone I met today, or that other people introduced me to. I’m a cofounder of FEW [Forum for the Empowerment of Women, a Black lesbian organization created in 2002] and part of several associations so many people are from there or allies to these queer organizations, who then became participants in the series. As part of this community myself, I like to photograph people how I would liked to be photographed. I wish I could give a camera to each and every queer person out there. Because if we could all photograph ourselves, the archive would be bigger and people would get to tell their stories better. Behind each portrait you see, there is somebody’s biography. Fifty pictures means there are fifty stories being told, so a hundred families’ when including mothers and fathers and grandparents. But within those family members, how many understand us? In our queer families, we can adjust, but in biological families, it can be a mess: if your father is super homophobic or your sister is transphobic, it’s a lot of emotional luggage to carry with you.

“Everywhere I go, I find trash that becomes treasure to me.” – Zanele Muholi

In 2012, you faced a tragic even when your studio in Cape Town was robbed and you lost 5 years of work. What impact did it have on your career?

2012 was one of these difficult times. While there were a lot of hate crimes happening at home, my flat was robbed when I was preparing for a big exhibition. To this day, I think I was robbed from someone who maybe knew what I owned and wanted to silence me from what I was sharing and documenting. Even if that experience was very painful, it was a pivotal moment for me: many great things happened afterwards and I still managed to have a very beautiful first solo show in Paris. Now here I am back to Paris eleven years later with my first retrospective, this time. More than getting my revenge, I would rather seize this opportunity to make a statement and prove that even when something that bad happens to you, you can still rise up.

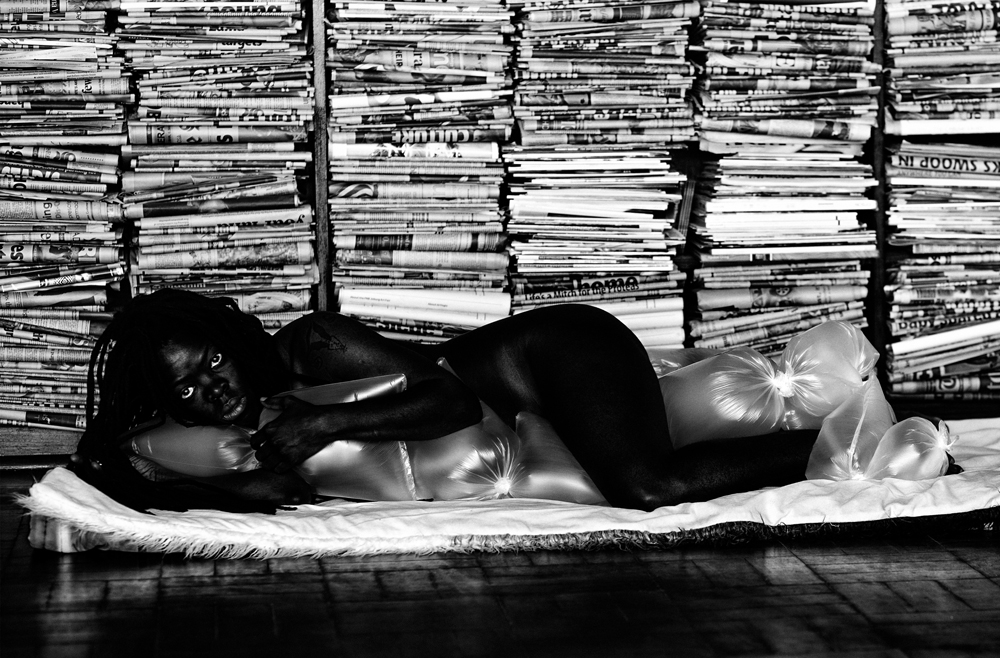

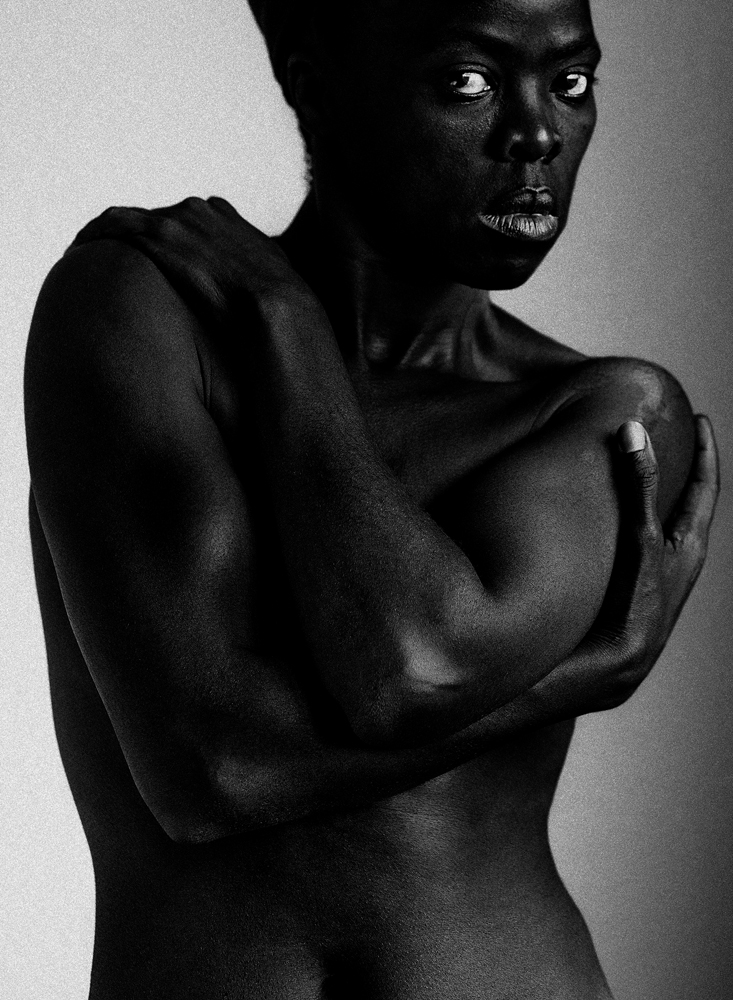

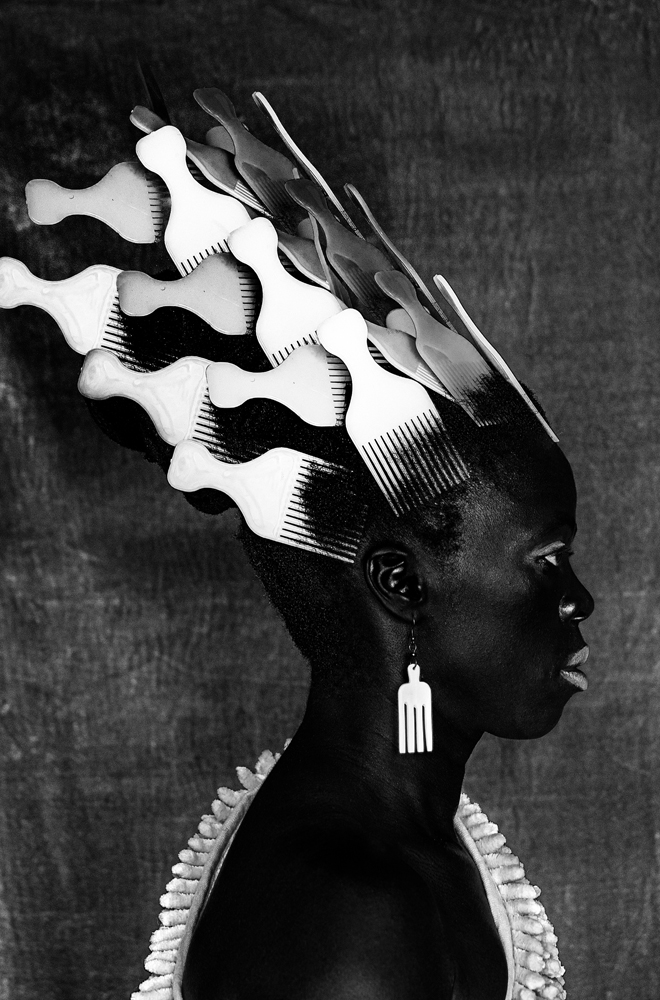

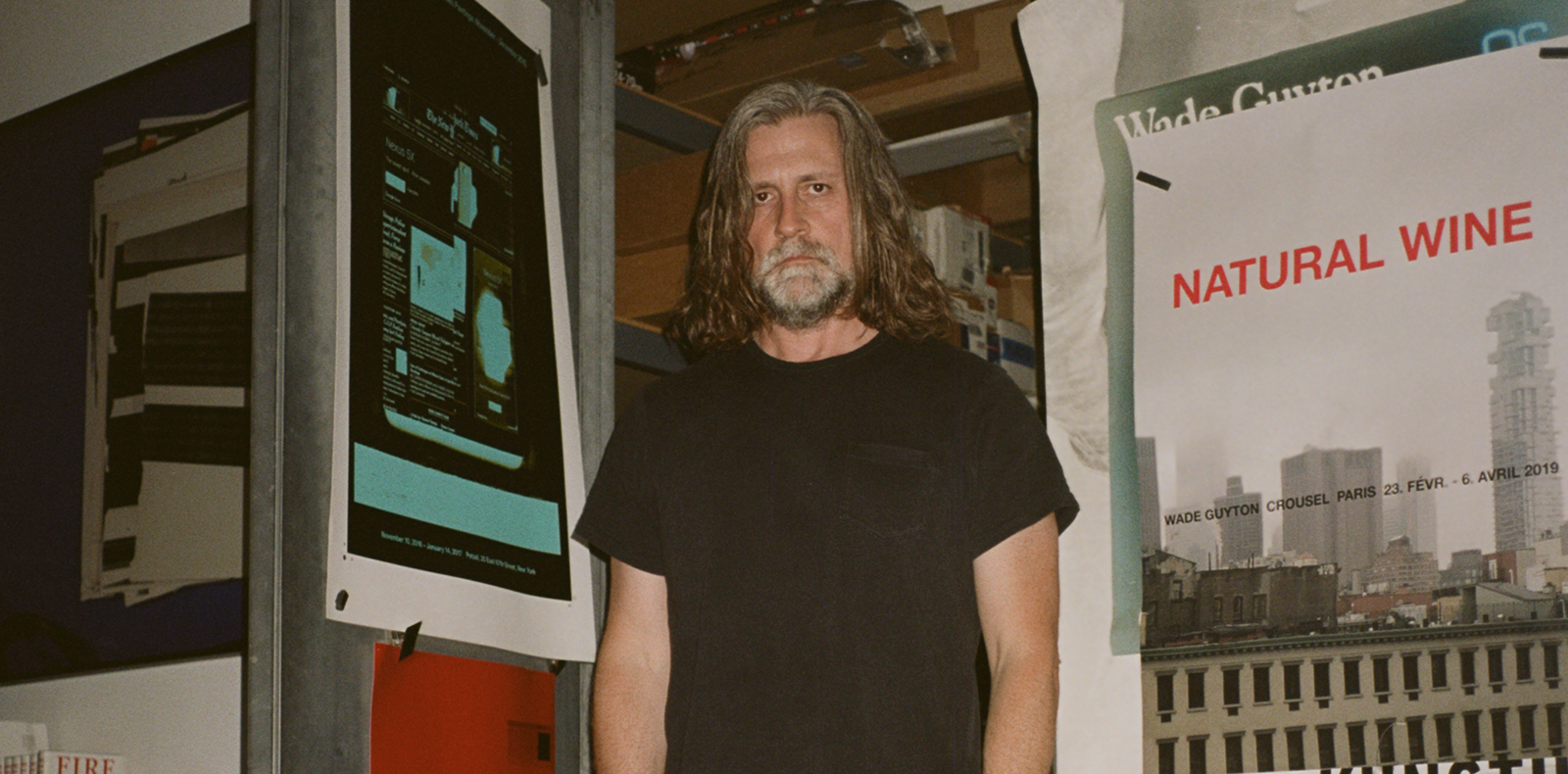

2012 is also the time you started your famous self portraits series Somnyama Ngonyama, where you have photographed yourself in many different places in the world while keeping a strong visual consistency. How do you succeed in doing so?

Everywhere I go, I find trash that becomes treasure to me. Be it clothing or materials dropped for pick up in the streets, there are always interesting things t can turn into something beautiful to wear. I carry my tripod, my remote control and my camera everywhere I go, so making these self portraits is actually easier than making portraits. Mentioning the places I photographed myself in the works’ titles is still important to me, because it can be challenging to photograph myself in some places. So these portraits are very much about my luck of being what I am and do what I do today. In the end, they all are about life itself.

Today, you’re one of the most famous South African photographers in the world. Do you feel you’ve opened up a path for Black queer creatives to walk into?

I could definitely say I paved the way for many. People have written me telling me my work has empowered them to go through their childhood and help them deal with their identity. Sometimes, even parents come to me on behalf of their children! Today, my work is also used for academic purposes, where it reaches out to many other publics. So once it goes to those spaces it means it cannot be reversed. I’m very honored to say that finally, our community is recognized and given the respect we have longed for for years. In Africa, it has taken so much time. Several texts have been written about these issues but it’s still not enough! That’s why I talk about allowing people to tell their own stories. Could you imagine being 50 or 60 years old and never coming out until your parents died?

”I wish I could give a camera to each and every queer person out there.” – Zanele Muholi

In 2023, what are the biggest challenges for a visual activist like yourself?

Today, we cannot defend human rights without visuals. As a South African person, I could say how beautiful my country’s constitution is, but it is still a document put together by people who understand it. There are so many of us who want to be protected by this document, but where do we appear? Political presence is what visual activism is all about. Seeing work like mine here means that, before I reached that goal, there are embedded issues that connects us to the state’s politics and society, and how they affect us. South Africa is actually one of the most progressive countries in the continent and in the world: we are one of the only African countries to have a constitution, gay marriage, adoption rights… So with my exhibition in Paris, the question should rather be about what has been done in France to share our visual narratives and welcoming people from all over the world. In Toulouse currently, there is this case about an event where drag queens would tell children a fairytale featuring a transgender character. This workshop faced backlash from the far-right and the city’s mayor, who called it propaganda, while they actually just intend to inform children about the existence of trans people. Rather than always shifting the focus to the problems we face in Africa, let us examine what is happening here in Europe and how the law violates the locals communities. To me, that is what visual activism is all about today.

Zanele Muholi, from February 1st to May 21st, 2023, at Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France.