19

19

Ron Mueck’s gigantic artworks invade the Fondation Cartier

The great Australian sculptor Ron Mueck makes his comeback at the Fondation Cartier for his third exhibition in the Parisian institution. A good opportunity to dive into a quite impressive and disturbing practice, enriched with new spectacular creations.

by Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 19 July 2023. Updated on 22 October 2025.

In today’s art world, the word ‘excess’ is unreasonably used, and at times, overused. However, as far as Ron Mueck’s work is concerned, the term takes back its original meaning. The proof is at the Fondation Cartier, where the Australian sculptor is unveiling a monumental installation as part of his new solo exhibition until fall. A hundred of white resin skulls, each up to 1.50 meters high, pile up in the architectural space designed by Jean Nouvel like a labyrinth of sinuous cavities. Surrounded by that build-up of heads, which draws a pathway through the exhibition space, the visitors have no choice but to immerse themselves in this ultra-modern, gigantic vanitas. The skull, a key element of that pictorial genre born in the 17th century, is no longer alone but available in great numbers here. Once painted on a canvas, it now stands up to the individuals’ size, confronting them head-on with the “transitory nature of human life”, as the historian and specialist in vanities Ingvar Bergström coins it. Ron Mueck’s Mass (2017) is a genuine feat that reveals a new side of his sculptural practice to the European audience. A twenty-four-year-old practice renowned for confronting the confusing realism of human bodies and the disruption of scale.

A hyper-realistic sculpture that shakes up the relationships of scale

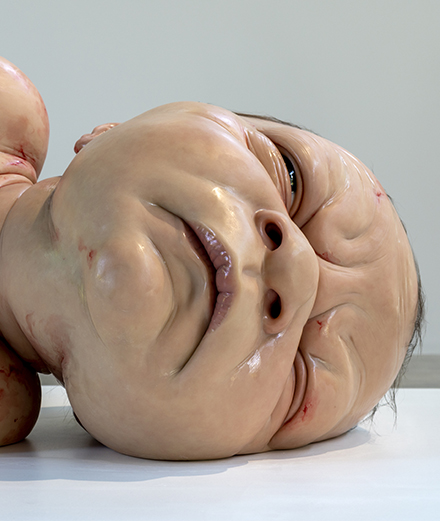

It will take a few more steps to the next large room on the ground floor of the Fondation Cartier to distinctly make out the Australian artist’s signature stroke. A giant baby (A Girl), stretched out on a white base, immediately stands out thanks to her size and realism. Wrinkled skin, traces of blood, damp hair on her skull, umbilical cord… Ron Mueck spares the public no detail. Since the late 1990s, the artist has been working on recreating the flesh of living beings – mainly humans – with surgical precision, usually going from a clay mold to a volume made of resin or silicone that he would eventually paint and embellish with hair, clothes, and other additional elements. This remarkable technique has established the 65-year-old artist as a leading figure of hyper-realist sculpture, a movement that emerged in the United States in the 1960s characterized by the use cutting-edge techniques and materials to offer the most faithful representations of life. Yet, Ron Mueck denies that affiliation. To him, everything is about of proportions.

Either barely taller than a vase or twice the size of the average man, his spectacular artworks skillfully depart from nature and trigger a powerful and troubling strangeness in the visitor, who remains stunned by the impressive naturalism of their texture and details. A Girl (2006) is the perfect illustration, as the usual few dozen centimeters of a newborn now translate into a five-meter-long body, which looks repulsive, even monstrous, yet very faithful to its model. This ambivalence has shaped a doorway to the sculptor’s singularity since his debut in 1996. Unlike his predecessors Duane Hanson and John De Andrea, Ron Mueck does not seek to transcribe reality, but rather to use its components to better disturb the viewers to the point where they see themselves as Lilliputians in a world of giants.

A rare artist, against the current

As a former puppeteer for The Muppet Show, the Ron Mueck pays the same attention to details in each one of his works, whatever the size. Given the size of his artworks, one might picture him surrounded by dozens of assistants in a neat studio, like his colleagues Daniel Arsham, Anish Kapoor, or the Scandinavian duo Elmgreen & Dragset. In fact, the opposite is true. A few years ago, the artist left London to set up his studio on the Isle of Wight, where he creates everything all by himself, from the first models and casts to the last hair on the resin. “Everything has to come from him, even the most insignificant gesture,” Charlie Clarke explains during the installation of the exhibition. The latter, a close friend and collaborator of the artist for over twenty years and the associate curator of his new project, manages the logistics required for the works, from their conservation to their hanging, which he constantly discusses with the artist, without ever touching the artworks. “I’m like an extra pair of hands, an extension of him. I help, assist, and advise him, but I never replace him,” the Londoner explains, acting like the artist’s spokesman for the media. Ron Mueck refuses to speak publicly about his work and rarely agrees to be photographed, shunning as much as possible the mundanities that go with the microcosm of contemporary art. During the press visits scheduled a few days before the opening of the exhibition at the Fondation Cartier, the artist, who is quite involved in the hanging of his works, stood in a corner to add the final touches of paint on his sculptures, rather than answering the journalists’ questions, to his greatest delight. “Ron has always favored craft over discourse,” Charlie Clarke states. “For him, a work should stand on its own.”

The Fondation Cartier first revealed Ron Mueck’s work to the French public in 2005. Since then, the Parisian institution and its director Hervé Chandès have been among its most fervent supporters, as reflected by this third solo exhibition. Throughout the 2000s, his work has been exhibited worldwide, from the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh to the Venice Biennale, and the artist has been represented by the great Hauser & Wirth Gallery for almost ten years, before joining the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery. Despite his international reputation, Ron Mueck’s creative process remains quite slow because of his practice, which thus goes against the flow of the market’s injunctions to continually produce more art and faster. For the hundred giant skulls of Mass (2017), an installation initially produced for the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, it took the artist an entire year to design an original mold that would satisfy him, and another year to make 99 copies of it… not to mention the two-month sea journey on twelve different ships from Australia to France. The monumental dimension of his works is even more striking when one contrasts the intimacy and solitude of his practice with the considerable logistical and human effort required to move and exhibit them.

Today, only forty-eight artworks exist and are either stored at the artist’s studio, at his gallerist’s, or at the collectors’ homes. In 2011, Christie’s auctioned his sculpture Big Baby for nearly a million euros. The artist has actually made a habit of going through his entire body of work and extracting an original selection for each new exhibition. For instance, a miniature newborn baby made in 2000, the artwork Man in a Boat (2002) depicting a tiny man sitting in a boat, and two previously unseen sculptures, will be gathered by the artist in the basement of the Fondation Cartier this summer. Ten years ago, in that same building, he orchestrated the unlikely encounter between a large, hanging chicken and a giant couple – an old man and woman wearing swimsuits and lying down under a parasol. In 2005, a giant young woman lying down on a bed was waiting for the visitors in the basement, while the face of black woman, as tall as a child, emerged from a picture rail to catch the viewer’s eye on the ground floor.

A timeless and universal work that continues to renew itself

Although Ron Mueck pictures his work as a long continuum with no breaking point, this new exhibition reveals some sculptural innovations. Among the dazzling white monochrome skulls – a sharp contrast with the usual yellowish hue of ageing bones – and the three gigantic black dogs in the basement, the artist gradually emancipates himself from realism and focuses on the effect caused by an increasingly absolute work and its overall experience. Like Cerberus, the three-meter-high trio of dogs seem to keep the space dimly lit, confronting the visitors with its immensity and menacing presence. Though faithful to his hand-crafted technique, Ron Mueck also incorporated new technologies to his toolbox, such as 3D printing, which helped him design this exceptional piece of art. Yet, the most surprising artwork of the exhibition remains the small sculpture made of red clay – a highly expressive scene staging five men tying up a pig on the ground. For the first time in his career, the Australian artist chose to leave his work unfinished, with raw clay and a few fingerprints on it, as a deliberate form of imperfection. “Ron was working on this new series of sculptures and wanted to include them in the catalogue,” Charlie Clarke says. “So, he chose to present this one, even though it was still a work progress, as if he was making a freeze-frame.”

At odds with the thematic display, that is exactly what this new exhibition offers – the freeze-frame of a monumental and ‘timeless’ work, deprived of any chronological reference, which fosters an endless reflection on the human condition that will extend far beyond our respective lives. Through a fortunate turn of events, the very last work of the exhibition arrived right at the end of our visit. A replica of the White Skulls cast in bronze was unloaded from a lorry and placed at the entrance of the foundation. Weighing over one ton, the black vanitas morphs into a megaphone for both the artist and the famous aphorism memento mori. Proof that excess can also be humbling in the face of the inevitable finiteness, and even more so when it mobilizes universal icons that will stand the test of time.

Ron Mueck, until November 5, 2023 at the Fondation Cartier, Paris 14th.