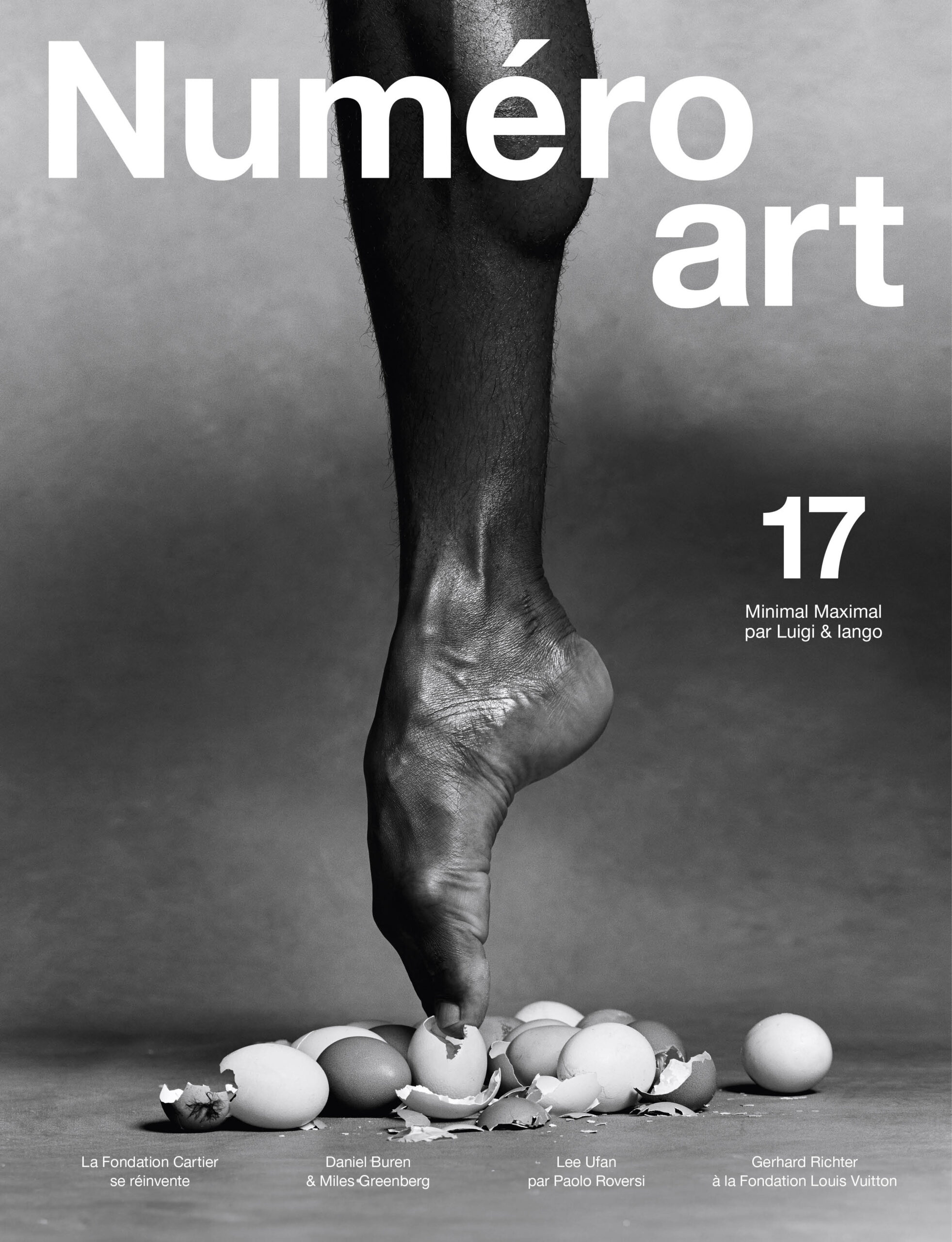

7

7

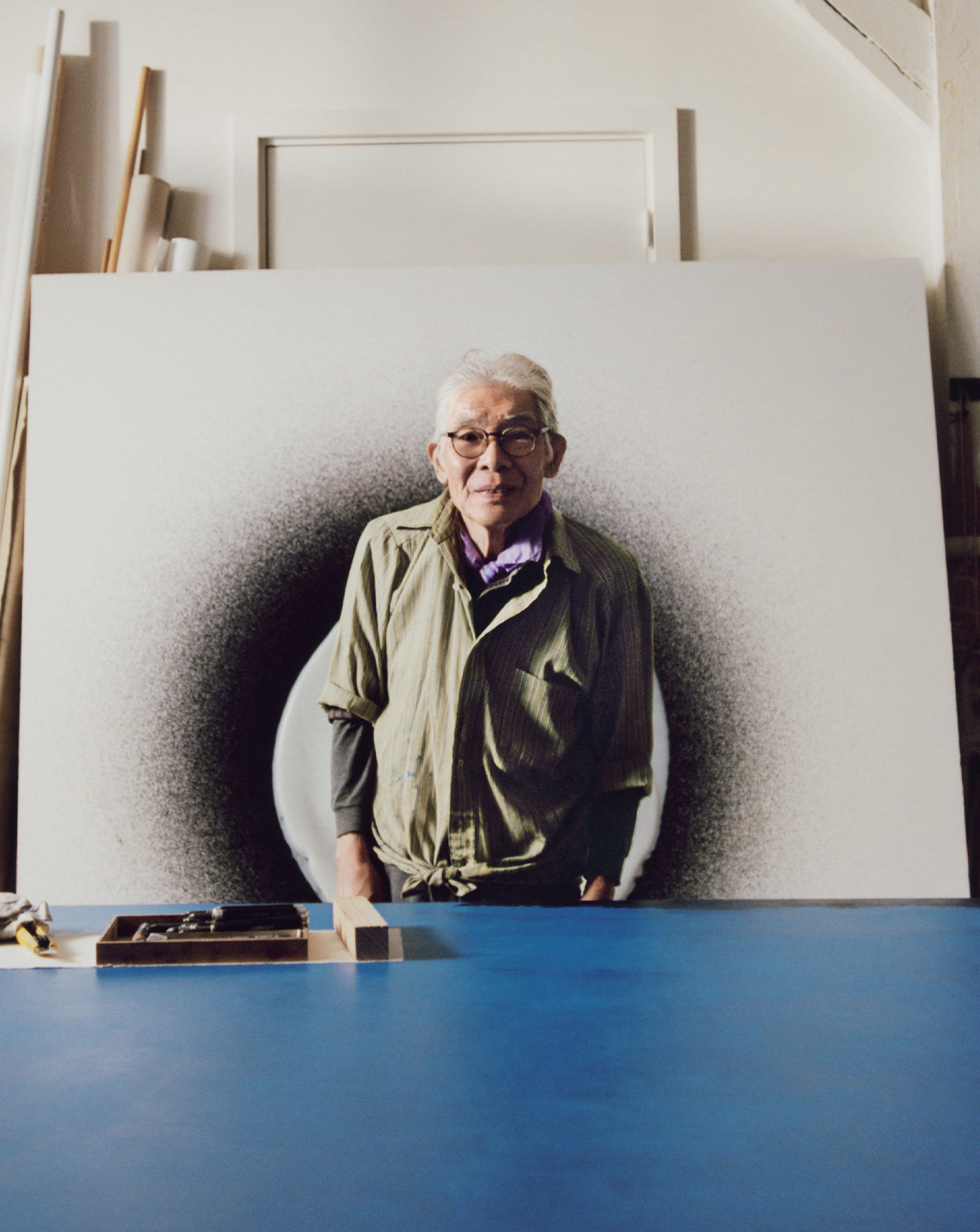

Dive into Takesada Matsutani’s atelier, exhibited at the Hauser&Wirth Paris gallery

As wildly creative as ever, the 87-year-old Japanese artist invited Numéro art into his studio on the occasion of a new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth. In the heart of Paris’s 11th arrondissement, Takesada Matsutani took us on a guided tour through 60 years of extraordinary production, from his first pieces inspired by the Gutai movement to his colourful hard-edge paintings and his monumental paper-and-graphite installations.

Propos recueillis par Thibaut Wychowanok.

Interview with artist Takesada Matsutani in his parisian studio

Numéro Art : n the early 60s, you came up with the brilliant idea of working with vinyl glue, which has become your signature. Inflating it directly on the canvas, you challenge the boundaries of painting, expanding it into three dimensions in a way that is sensual and even erotic, given how the glue evokes ejaculations and ovulations. Where did this idea come from?

Takesada Matsutani : I was born before the war in a rather desperate Japan where imagining such a thing would not have been possible. After the war, material conditions were hard, of course, but our minds were much freer. Nonetheless, I was still influenced by Cubism and Surrealism – Western art, in particular French art, was everywhere in Japan at the time. Moreover, my painting was entirely figurative. Then I discovered the Gutai movement [an important group of Japanese iconoclasts who promoted a “concrete” art through which they sought to breathe life into matter]. Its members seemed much freer to me – they were starting from scratch. So I decided to get closer to the founder, Jiro Yoshihara. This was in the early 60s. Yoshihara kept rejecting my work, saying “No, no, and again no!” I’d show him a piece and he’d pull out a catalogue from the shelf and say, “Look, Fontana has already done it,” or, “Jackson Pollock has already done it. You have to do something that’s never been done before, something new!” That was the mantra of the Gutai movement. I needed to come up with and create new images. Inspiration came from a friend who worked in the medical faculty. I was able to observe cell samples under a microscope – I was fascinated by these organic and somewhat sexual forms. All of a sudden, a new image came to me: it wasn’t a sculpture but a material, and a canvas that was flat yet three-dimensional. I found some vinyl glue, which I inflated on the canvas, at first by blowing into myself. It became a sort of skin. Then I let the wind and chance do their thing, piercing and shaping it. Sometimes I intervened by turning the canvas around… And Yoshihara finally accepted my work

I’m not a philosopher. I feel time, I feel the cosmos. We live inside the impermanence, the long reach of cosmos.” – Takesada Matsutani

The year was 1963 and, as in some of your later works (I’m thinking of the monumental installations you began in 1979, which were often associated with performances), you manipulated chance. You don’t represent nature or life – you create it, you make it happen, along with its share of chaos. Even the trace of your breath is captured and preserved. Would you say the idea of the cosmos lies at the heart of your work?

Things don’t come through ideas, but through action. I’m not a philosopher. I feel time, I feel the cosmos. We live inside the impermanence, the long reach of cosmos. My knowledge and my conscience time, and meditation, and on the are fed by my sensations and my emotions, by other the present moment, or a what I feel and experience. Why did I choose succession of moments, and the to use graphite pencils in 1977? Because I had occasional desire to freeze that a lot of time on my hands. I knew no one! All moment for eternity, like that little I had at my disposal was a blank sheet of incident of life captured forever paper. What could I do? I’m not a poet, I wasn’t going to write stories. So I picked up a pencil and drew a line every day, then another, and another until the surface turned black. Naturally I thought of the Japanese tradition of calligraphy. But copying wasn’t allowed – I had to do something new! So I started doing these 10 m-long formats that I would hang up. To come back to the cosmos, the best way to be part of it is to undertake this type of work, to put yourself in this state of mind – one line after another, again and again. That’s a good start. A small part of the cosmos we live in.

This makes it sound like your work is based on a sort of temporal duality: on the one hand impermanence, the long reach of time, and meditation, and on the other the present moment, or a succession of moments, and the occasional desire to freeze the moment for eternity, like that little incident of life captured forever when the glue sets…

Yes, time is in motion. Every moment is unique. Every moment is different.

Arriving in Paris in 1966 was an important moment in your life. You took part in a competition and won a six-month residency, but afterwards you never really left the city. Your studio and your archives are now to be found in the 11th arrondissement. What happened?

I ask myself the same question. There’s no short answer. Maybe you have to go back to my early years. I didn’t go to school much. Of course, secondary school was compulsory, but at 15 I contracted tuberculosis. I had to stay in isolation at home or in a sanatorium. I drew a lot. One or two years went by. Nobody needed me. They needed a healthy young man! So I turned to painting. And I ended up enrolling at the municipal school of arts and crafts in Osaka. But I only stayed a few months! I’m self-taught – I got my education through experiencing things for myself. France was a new experience… I only knew the world through books, films, and photographs. But I wanted to see it for myself. That same year I went to Egypt, Italy, and Greece. And in 1967 I felt the need to start working again, in Paris.

What made you frequent the Atelier 17 studio, where you made many engravings and became the assistant to Stanley William Hayter, an artist who breathed new life into the art of engraving with his abstract constructions? It was there that you met your wife, Kate Van Houten, who introduced you to screenprinting, which has since played a very important role in your oeuvre. Then you went on to produce work in the hard-edge style – multi-hued paintings that featured abrupt transitions from one area of colour to another.

I knew Hayter’s work from a Tokyo Biennale in the 1960s at which he was awarded the main prize. I really wanted to learn the techniques of engraving – the idea in my mind was to make flat versions of my organic, sensual three-dimensional works. Once again, I needed to come up with something new. Hayter also taught me perspective, which I then incorporated into my work. As for hard edge, I was tired of black and white at the time. I needed a new challenge that would allow me to mix the colours.

Takesada Matsutani’s paintings exhibited at the Hauser&Wirth Paris gallery

Some of your compositions follow a logic of “propagation” and “development,” which is how you refer to some of your series. By this do you mean like a virus or a cell that multiplies?

Yes, we’re back to what I saw through the microscope – the bacteria, and all sorts of things that were growing. It’s also about biological propagation linked to sexuality, of course.

So can we say that sensuality and the body are an important part of your work?

During my exhibitions, I like to sit in a corner and listen to what the visitors in the gallery tell each other about them. Do you know what they say about my pieces? “I want to touch them!

“Matsutani” exhibition, until May 19th, Hauser&Wirth gallery, Paris.