27

27

Interview with Justine Triet : “For a long while I was frightened of Anatomie d’une chute, it gave me nightmares.”

The director of Victoria (2016) and Sybil (2019) – films driven by powerful female protagonists – was this year honoured with French cinema’s highest accolade, the Palme d’or at the Cannes Film Festival. Her winning opus, Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall), a courtroom drama about a woman accused of murdering her husband, allowed Triet to explore her favourite theme, the power balance within the couple.

Interview by Olivier Joyard,

Pictures by P.A Hüe de Fontenay.

Published on 27 November 2023. Updated on 20 June 2024.

The director of Victoria (2016) and Sybil (2019) – films driven by powerful female protagonists – was this year honoured with French cinema’s highest accolade, the Palme d’or at the Cannes Film Festival. Her winning opus, Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall), a courtroom drama about a woman accused of murdering her husband, allowed Triet to explore her favourite theme, the power balance within the couple.

Interview with director Justine Triet on the film Anatomy of a Fall, Palme d’Or 2023

Numéro : How do you feel about the fuss that followed your Cannes acceptance speech, in which you criticized Emmanuel Macron and the French government?

Justine Triet : Even though I didn’t think I was going to win, I started preparing my speech two days before the ceremony just in case. I couldn’t get my head round the idea of not pointing the camera at what has happened this year. And my first thought was the question of pensions and retirement, because my first feature film, La Bataille de Solférino, took place in the street and dealt with themes that are still relevant today. I felt it was fundamental to talk about what had happened – the whole of France rising up against a reform that was pushed through by force, and the link between that and the current state of cinema. But I hadn’t anticipated the uproar it would unleash, nor the way my words might be misconstrued. I wasn’t talking about me but about the young; I hadn’t anticipated the culture minister’s communications stunt with her Tweet… It’s been corrected in the press since. In any case, I have no regrets – it was the least I could do.

“My family has a complex past that I don’t talk about much.” – Justine Triet

Godard and Truffaut before you spoke up in May 1968, saying that the Cannes Film Festival should be suspended while everyone was demonstrating in the street…

They achieved so much more than me, but obviously I had them in mind. I’m glad my win helped wake up people’s consciences a bit. I didn’t go to film school, I began by making movies that cost nothing before shooting high-production dramas, with audience figures ranging from 20,000 to over 600,000. For me, the question of pensions and what we spend tax-payers’ money on is linked to that of spending in the film industry: should we continue to allow room for the production of movies that are not obviously commercial [France’s Centre national de la cinématographie (CNC) provides financial help for movie-making by paying an advance on ticket sales]? The CNC’s help makes a huge difference – without it I couldn’t have made La Bataille de Solférino, my breakthrough film.

You didn’t go to film school but instead studied fine arts.

In art school I took a video class that introduced me to 1970s cinéma-vérité and documentaries.

And then you started making movies at around the age of 30.

That was when I finally realized you could make a living from film-making. One thing led to another, with a prize at the Berlin Film Festival for Vilaine Fille, mauvais garçon [2012], presented to me by the German actress Sandra Hüller. That was the first time we met, long before we worked together on Sibyl and Anatomie d’une chute. Then I became pregnant, and during those nine months decided to write La Bataille de Solférino.

“ I enjoyed creating a character who’s not always terribly nice. I had her say things that, in a man’s mouth, would be profoundly misogynist.” – Justine Triet

What was the starting point for Anatomie d’une chute? The desire to work with Sandra Hüller again?

I really wanted to film a foreigner who doesn’t speak French so well. Sandra came to Paris very early on in the writing, just before the COVID lock-down. I didn’t think Arthur [Harari, Triet’s life partner, who is also a film director] and I would spend two years writing the script – I thought it would take barely three months. And to be honest, he would never have agreed to devote so much time to one of my movies! Right at the start of the process, I remember looking at my daughter, who was nine or ten at the time, and wondering what she really knew about me. My family has a complex past that I don’t talk about much. I said to myself, “She’s growing up, one day I’m going to have to talk to her about it.” Then came the idea of a child caught up in total chaos brought on by the machinery of justice. The idea of a courtroom film was also in my mind, but the whole thing came together when I imagined the mother-child duo. The kid trusts the mother, then all of a sudden that trust cracks.

The film deals with a raw subject: how a woman who is professionally more successful than her husband disturbs the social order.

That isn’t exceptional in itself, but the fact she does it without feeling any guilt, and without asking permission, creates a profound imbalance in her marriage to another writer. I enjoyed creating a character who’s not always terribly nice. I had her say things that, in a man’s mouth, would be profoundly misogynist. When she snaps, “I don’t know anyone who can’t manage to write because they have to do the shopping,” I’m aware that if a man said that he would be spitting in the face of the half of humanity that spends its time doing the shopping and looking after the children. There’s clearly something provocative in her. She freed herself from the norm and does exactly what she wants.

“For a long while I was frightened of Anatomie d’une chute, it gave me nightmares.” – Justine Triet

Your film isn’t terribly optimistic about heterosexual relationships…

Perhaps, but I think there’s love between the couple in my film. They still tell each other things. At one point in my life, a man said horrible things to me. At the time, I felt I had two options: I could either think, egotistically, “He’s a monster, what he said to me is horrible,” or I could let his words resonate in me. And as it happened, what he said was sufficiently interesting for it to resonate in me. In the film, the heroine says to her husband, who’s suffering from writer’s block: “Your pride explodes in your brain before you even have the kernel of an idea.” It’s a way of telling him he’s not a victim, that he’s struck down by fear. You have to love someone to throw that at them. A couple is really dead when there’s no communication. But you’re right, I didn’t film a couple that’s in a good way. I was touched by Emmanuelle Richard’s book Les Corps abstinents about women who decide to stop having sex. I think this positive transformation of the old maid, the “sexually frustrated female” as she’s labelled, is fantastic. There’s no sex in my film – looking at each other is perhaps the most erotic act I shot.

Though never “sociological,” your films are marked by contemporary debates about the relationship between men and women.

I can’t imagine writing scripts that are based in theory: I think that would make for very bad movies. But my heroine is certainly a product of what’s going on these days. I always feel that, to survive, the couple has to continuously reinvent itself, and that you need to think about how to do that. “A room of one’s own,” as Virginia Woolf put it, is absolutely essential, and though it may sound banal, it really isn’t: most women don’t dare to claim it for themselves, and in a city like Paris it’s very difficult to obtain. Still, things are slowly changing. I have a 12-year-old daughter, so a lot of young girls come to the house. They have a tenderness and a benevolence towards each other that I don’t remember at all in my generation. The idea that real modernity lies in empathy is something that fascinates me.

Your films are both energetic and precise. How do you achieve that?

I made sure the shoot for Anatomie d’une chute was very lively, a sort of permanent experimentation. Since it was scripted in advance, I also tried to create feshness and movement through the camera. I was very inspired by a 1968 Richard Fleischer movie, The Boston Strangler, a masterpiece that’s both spontaneous and weird and alternates between two modes of filming, one classic the other violent. The directors I admire are often those who mix two ways of shooting. I find dogmatism and total control depressing.

Have you reached the end of a cycle with Anatomie d’une chute?

I’ve gone pretty far. Now I’d like to film a sort of daily diary with a camera in my hand. Even if Anatomie d’une chute wasn’t so expensive to make, I felt it was rather a heavy piece of machinery, without the “free gesture” feeling I’d known on previous shoots. I actually have two new projects I’m ruminating on – I “live” in my films for a while before setting them down on paper. For a long while I was frightened of Anatomie d’une chute, it gave me nightmares. I didn’t want to write the script, I found it too dark.

You’ll be “living” Anatomie d’une chute for a while yet as it travels round the world.

Even if I’m delighted by the success, promoting my movies isn’t what I enjoy most. I never know how to behave. It’s not a moment of pure joy.

What would be pure joy for you?

Vincent Macaigne told me something years ago: when you’re nobody, when you’ve achieved nothing, every transgression is possible. Once a label has been stuck on you, it’s different. But I like to throw it all away and start again, I love the idea of self-reinvention. To my eyes, film is a way of reinventing yourself all the time. That’s what I feel deep inside me. And that’s why my films all fight with each other and are never alike.

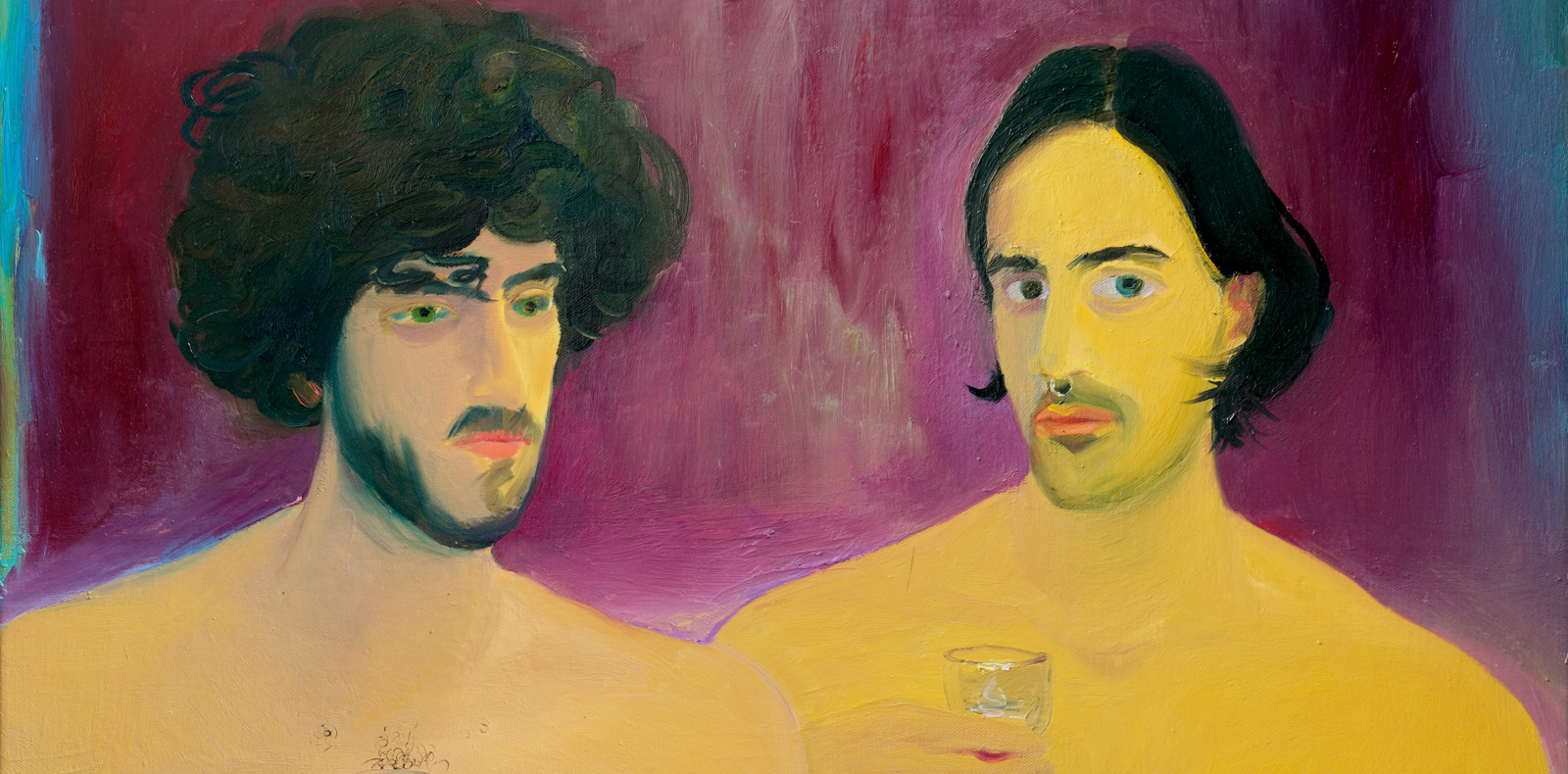

Anatomie d’une chute (2023) by Justine Triet.