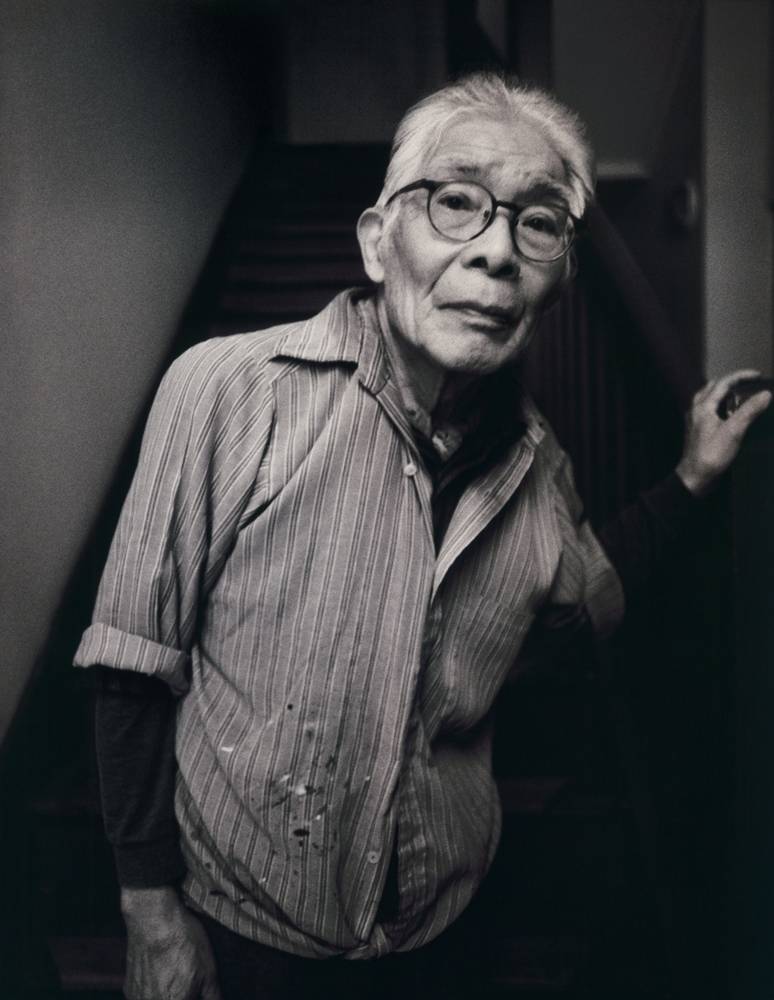

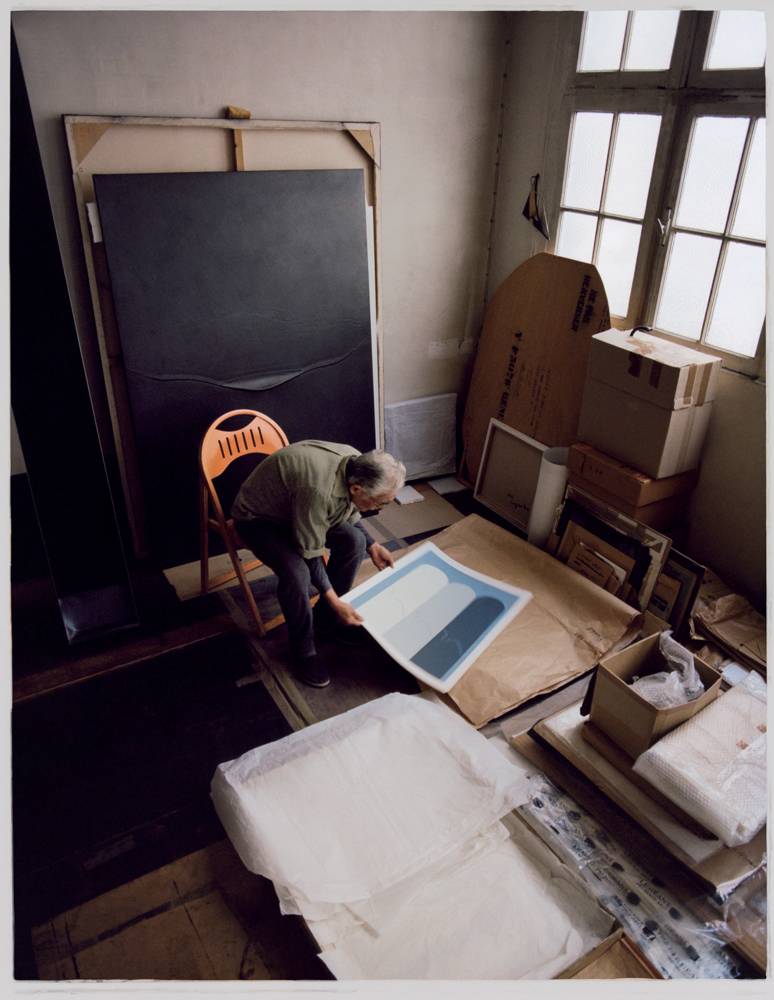

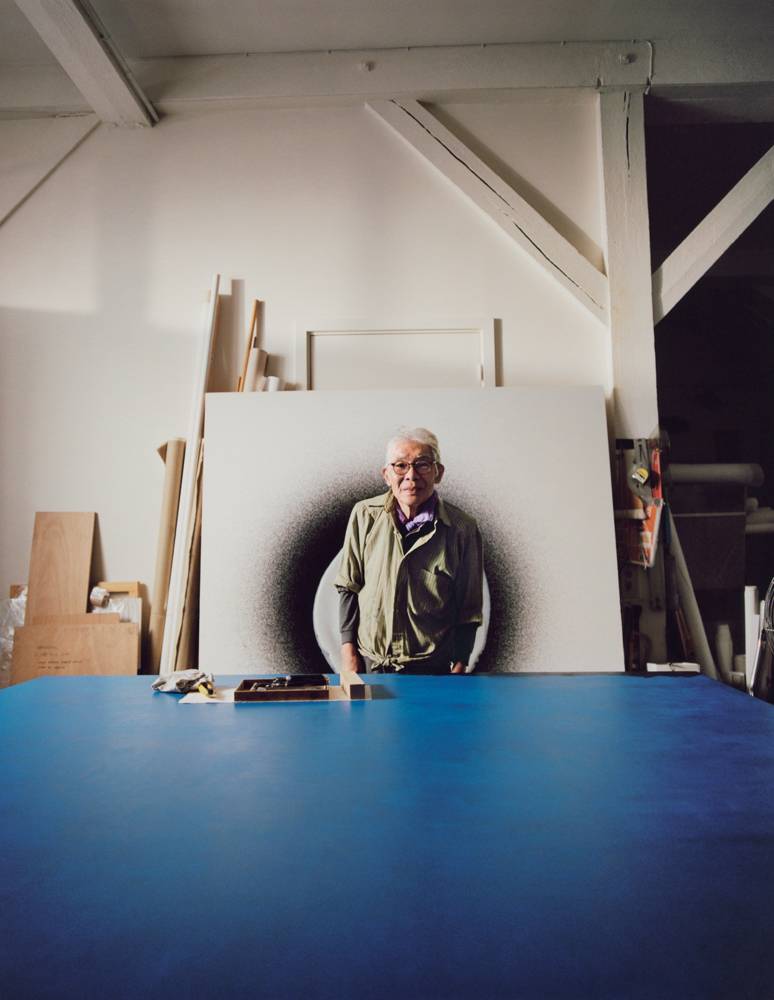

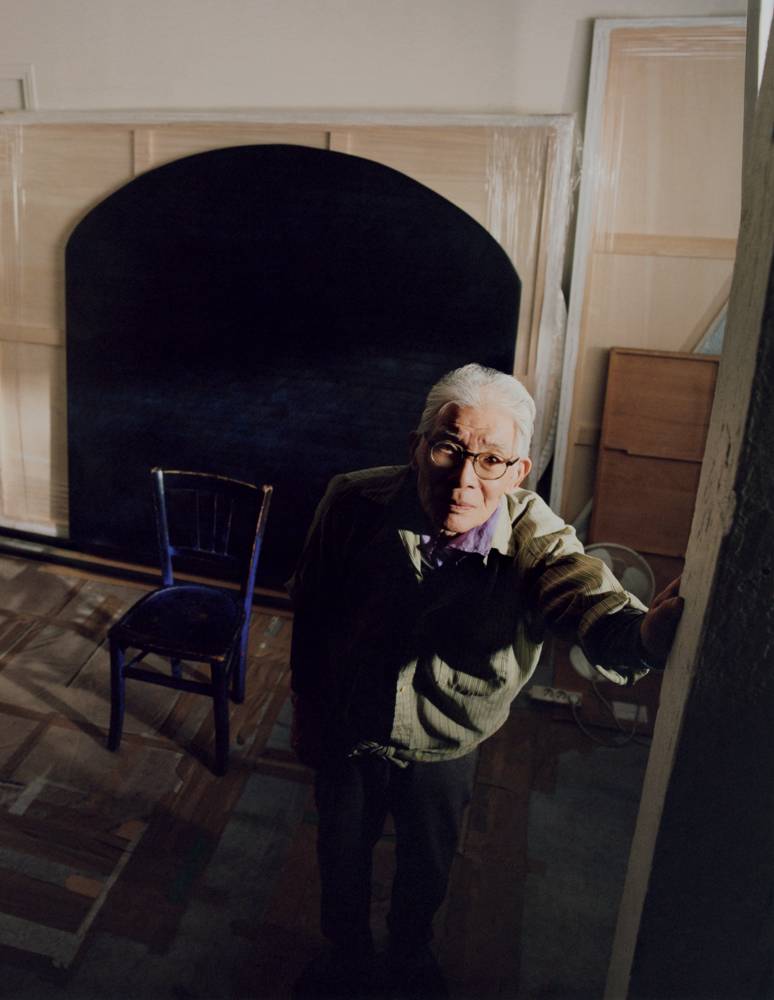

Dans l’atelier de Takesada Matsutani, exposé à la galerie Hauser & Wirth Paris

Takesada Matsutani, artiste japonais à la créativité toujours aussi folle malgré ses 87 ans, nous ouvre les portes de son atelier parisien à l’occasion de son exposition à la galerie Hauser & Wirth, ouverte jusqu’au 19 mai 2024. Visite guidée de 60 ans de création habitée par toutes les pulsations de la vie, de ses premières pièces liées au mouvement Gutai à ses créations colorées façon Hard Edge jusqu’à ses installations monumentales au crayon graphite.

Propos recueillis par Thibaut Wychowanok.

Portraits et vues d'atelier par Joshua Woods.

Rencontre avec l’artiste japonais Takesada Matsutani, dans son atelier parisien

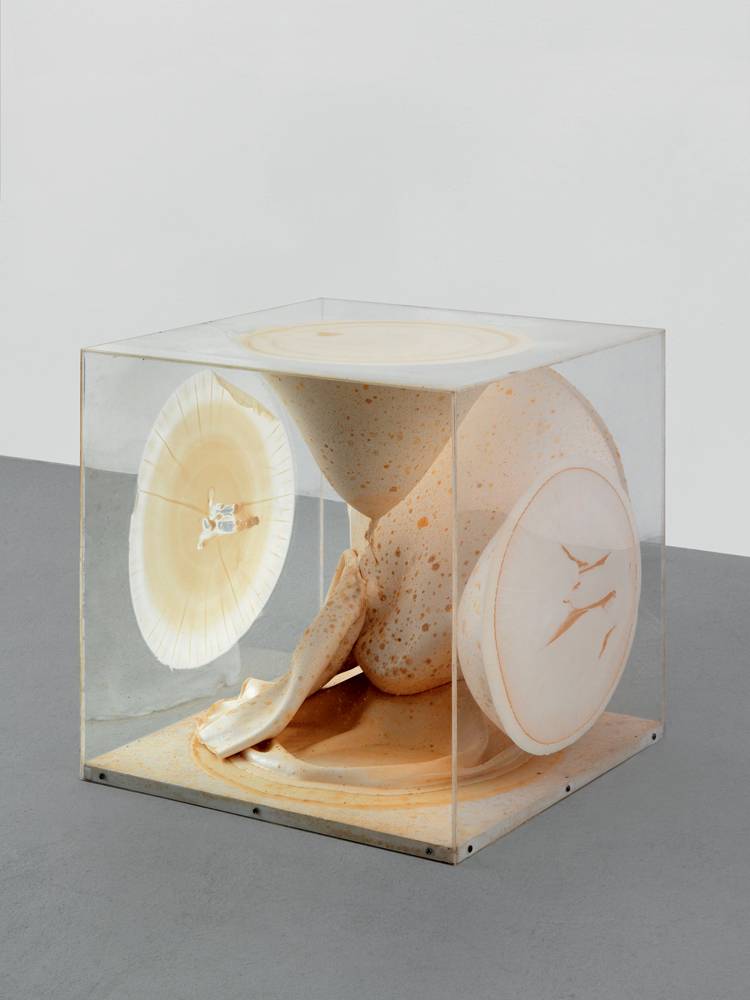

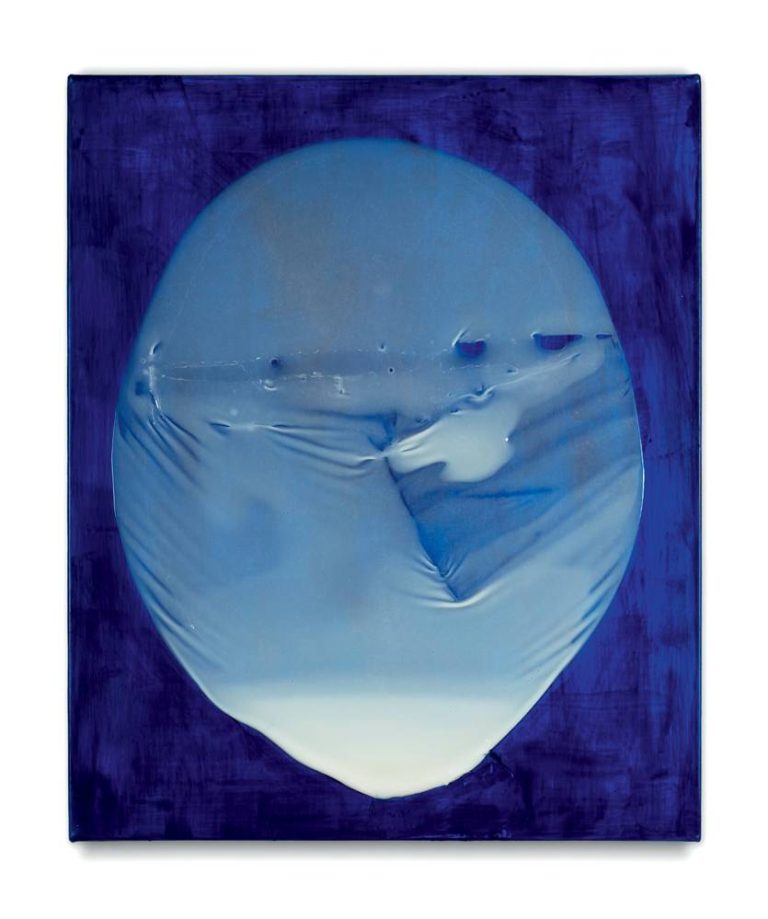

Numéro art : Au début des années 60, vous avez l’idée géniale de travailler avec un nouveau matériau, la colle vinylique, qui deviendra votre signature. Gonflant directement sur la toile, la matière sensuelle, voire sexuelle – tant le rendu évoque une éjaculation ou une ovulation– dépasse les frontières du tableau, qui s’étend en trois dimensions. Mais où cette idée trouve-t-elle son origine ?

Takesada Matsutani : Je suis né un peu avant la guerre au sein d’un Japon désespéré où imaginer une telle chose n’aurait pas été possible. Une fois la guerre terminée, les conditions matérielles étaient difficiles, bien sûr, mais notre esprit était bien plus libre. Mais j’étais encore influencé par le cubisme et le surréalisme : l’art occidental, et particulièrement français, était très présent au Japon à l’époque. Ma peinture était d’ailleurs totalement figurative. Puis j’ai découvert le mouvement Gutai [mouvement iconoclaste très important au Japon promouvant un art “concret” donnant vie à la matière]. Ces membres me paraissaient plus libres. Ils recommençaient tout à zéro. J’ai alors décidé de me rendre de me rapprocher de Jiro Yoshihara, son fondateur. Nous étions au début des années 60. Yoshihara rejetait continuellement mes propositions. Il me disait : “Non”, “Non” et encore “Non”. Je lui montrais une œuvre et il me sortait un catalogue de la bibliothèque en m’expliquant : “Regarde, Fontana l’a déjà fait.” Ou : “Jackson Pollock l’a déjà fait. Tu dois faire quelque chose qui n’a jamais été fait avant, quelque chose de nouveau.” C’était le slogan du mouvement Gutai.

J’avais besoin d’imaginer et de créer de nouvelles images. L’inspiration m’est venue grâce à un ami qui travaillait à la faculté de médecine. J’ai pu y observer des cellules au microscope : j’étais fasciné par ces formes organiques et un peu sexuelles. Tout d’un coup, j’avais une nouvelle image en tête : ce n’était pas une sculpture, mais un matériau et une toile plate et pourtant en trois dimensions. J’ai trouvé de la colle vinylique que j’ai gonflée sur la toile, d’abord avec mon propre souffle. Cela devenait comme une peau. Et puis j’ai laissé le vent et le hasard faire son œuvre pour la percer et lui donner sa forme. Parfois j’intervenais moi-même en tournant la toile… Et mes œuvres furent enfin acceptées par Yoshihara !

“Je ne suis pas un philosophe. Je suis dans l’action. Je ressens le temps, je ressens le cosmos. Ma connaissance et ma conscience sont nourries par mes sensations et mes émotions.”

Takesada Matsutani

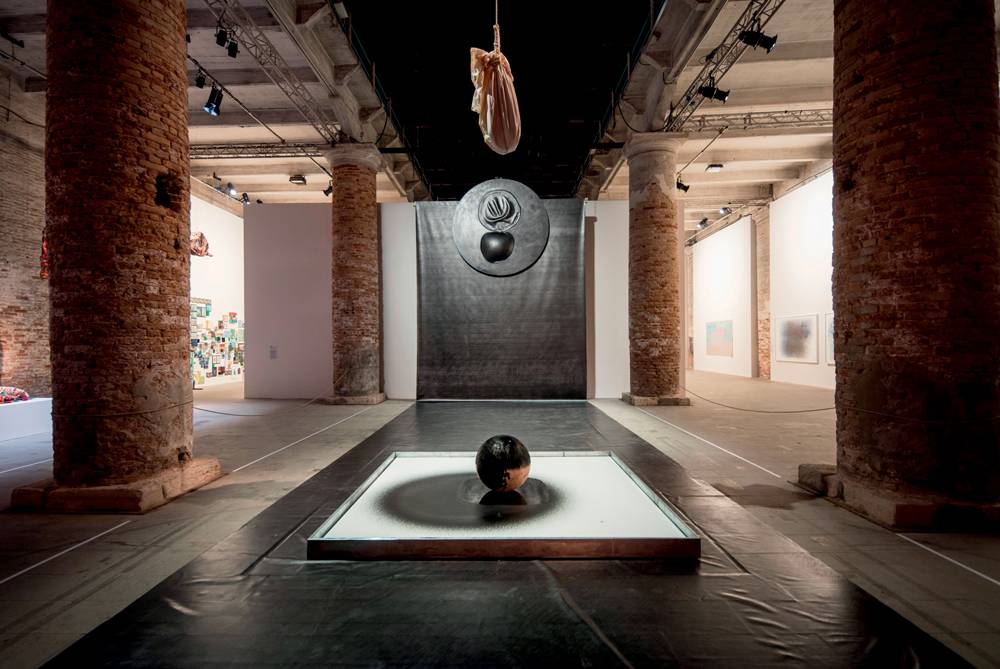

Nous sommes alors en 1963 et, comme dans certaines œuvres qui suivront – je pense à vos installations monumentales initiées en 1979 et souvent associées à des performances –, un hasard maîtrisé semble toujours participer à la création. Vous n’y représentez pas la nature ou la vie, vous la créez, vous la faites advenir avec sa part de chaos. Votre souffle lui-même y est gardé, capturé, préservé. L’idée du cosmos est-elle au cœur de vos œuvres ?

Cela n’arrive pas par l’idée, mais par l’action. Je ne suis pas un philosophe. Je ressens le temps, je ressens le cosmos. Le cosmos, nous vivons en son sein. Ma connaissance et ma conscience sont nourries par mes sensations et mes émotions. Pourquoi est-ce que je choisis d’utiliser des crayons graphites en 1977 ? Parce que j’ai beaucoup de temps. Personne ne me connaît ! Je n’ai qu’une feuille blanche à disposition. Et que puis-je faire ? Je ne suis pas poète. Je ne vais pas écrire des histoires.

Alors je me munis d’un crayon et chaque jour je réalise une ligne, puis une autre ligne, puis une autre ligne jusqu’à ce que la surface se noircisse. Évidemment je pense alors à la tradition japonaise de la calligraphie. Mais il ne faut pas copier ! Il faut faire quelque chose de nouveau ! Et je me lance dans des formats de 10 mètres de long que je suspends ! Pour en revenir au cosmos, la meilleure manière d’en faire partie est de réaliser ce type d’œuvre, de se mettre dans cet état d’esprit, une ligne après l’autre, encore et encore. Voilà un bon début. Une petite part du cosmos dans lequel nous vivons.

“J’ai trouvé de la colle vinylique que j’ai gonflée sur la toile, d’abord avec mon propre souffle. Cela devenait comme une peau. Et puis j’ai laissé le vent et le hasard faire son œuvre.”

Takesada Matsutani

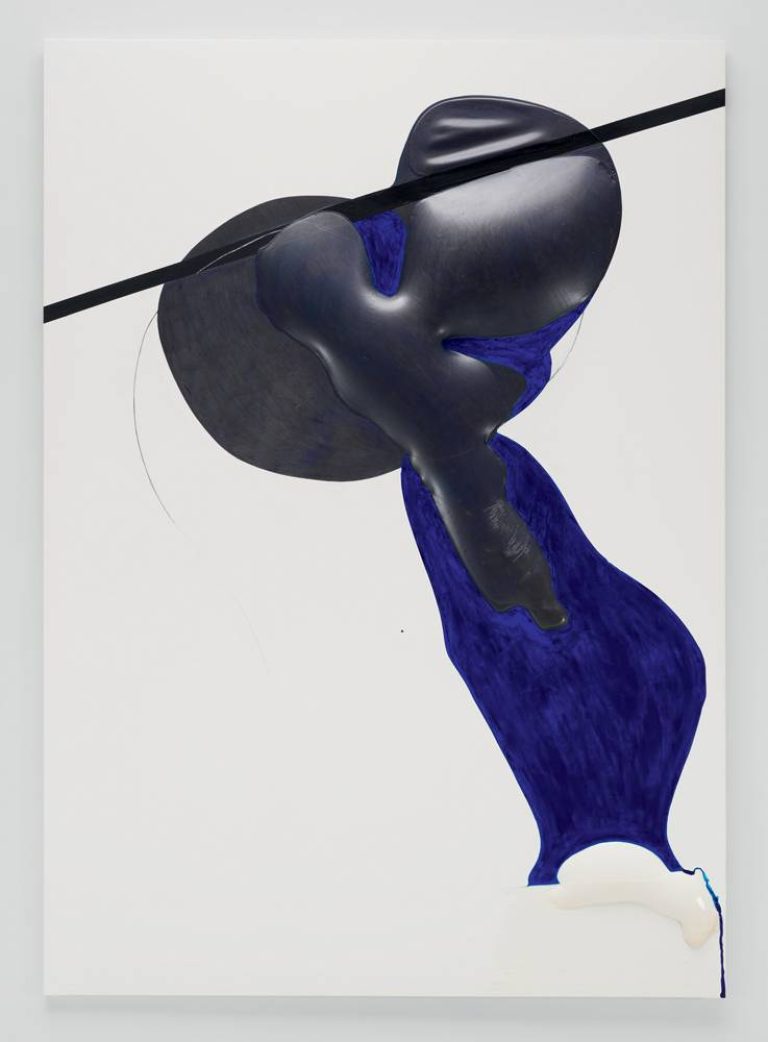

Takesada Matsutani, Circle Yellow-19 (2019). © Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Takesada Matsutani.

Un moment très important dans votre vie fut votre arrivée à Paris en 1966. Vous gagnez un prix à l’issue d’un concours : une résidence de six mois. Mais vous n’avez jamais véritablement quitté la ville depuis, et votre atelier, ainsi que vos archives, sont aujourd’hui dans le 11e arrondissement. Que s’est-il passé ?

Je me pose la même question. Il faut peut-être revenir à mes premières années. Je ne suis pas beaucoup allé à l’école. Bien sûr, le lycée était obligatoire, mais à 15 ans, la tuberculose m’a obligé à rester isolé chez moi ou au sanatorium. J’ai dessiné énormément. Un ou deux ans ont passé. Nul n’avait besoin de moi. On avait besoin d’un jeune homme bien portant! Alors je me suis tourné vers la peinture. Et j’ai fini par m’inscrire à l’École municipale des arts et métiers d’Osaka. Mais je n’y suis resté que quelques mois ! Mon éducation, je l’ai effectuée en autodidacte, en faisant l’expérience des choses. La France était une nouvelle expérience… Je ne connaissais le monde qu’à travers les livres, le cinéma et les photographies. Mais je voulais le voir par moi-même. Je me suis rendu cette même année en Égypte, en Italie et en Grèce. Et en 1967, j’ai ressenti le besoin de me remettre au travail, à Paris.

Pourquoi vous rendez-vous alors à l’Atelier 17, rue Daguerre, où vous réalisez de nombreuses gravures et devenez l’assistant de Stanley William Hayter, artiste qui a renouvelé la gravure avec ses constructions abstraites? C’est d’ailleurs là que vous rencontrez votre femme, Kate Van Houten, qui vous initie à la sérigraphie, très importante dans votre œuvre. Puis vous en venez à réaliser des peintures de style Hard Edge, des œuvres très colorées caractérisées par un passage brutal d’une zone de couleur à une autre.

Je connaissais le travail de Hayter grâce à une Biennale de Tokyo des années 1960 au cours de laquelle il avait reçu le Grand Prix. Je voulais absolument apprendre la technique de la gravure : j’avais en tête de rendre plates mes œuvres organiques et sensuelles en trois dimensions. Il me fallait à nouveau de la nouveauté. De Hayter, j’ai également appris la perspective, que j’ai alors intégrée à mon travail. Quant au Hard Edge, j’étais fatigué du noir et blanc à l’époque. J’avais besoin d’un nouveau challenge qui me permette de mixer d’autres couleurs.

Certaines de vos compositions continuent par la suite à suivre une logique de “propagation” et de “développement” – titres que vous aviez donnés à certaines de vos séries. Comme un virus ou une cellule qui se démultiplie ?

Oui, on en revient à ce que je voyais à travers le microscope. Des bactéries, toute sorte de choses qui se développaient. Il s’agit aussi de la propagation biologique liée à la sexualité, bien sûr.

La sensualité et le corps tient donc une part importante dans votre œuvre ?

Lors de mes expositions, j’aime me poser dans un coin et écouter ce qu’en disent les personnes qui la visitent. Savez-vous ce qu’elles disent de mes œuvres ? “J’ai envie de les toucher !”

“Matsutani”, exposition jusqu’au 19 mai 2024 à la galerie Hauser & Wirth, Paris 8e.