15

15

At musée du Quai Branly, ayahuasca opens the doors to a new world

À quoi ressemble le monde sous l’emprise de l’ayahuasca ? Jusqu’au 26 mai, l’exposition “Visions chamaniques” au musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac explore les effets de cette plante hallucinogène, qui trouve ses origines dans une communauté autochtone de l’Amazonie péruvienne, à travers la manière dont son expérience a façonné la création artistique, de cette région jusqu’à l’Occident. Un voyage captivant dans les profondeurs de l’âme humaine.

By Matthieu Jacquet,

By Matthieu Jacquet.

In 1990, when asked by a journalist whether he would be able to create without using any substances, the writer William S. Burroughs spontaneously delivered an eloquent answer: “I don’t think so”. The American novelist’s work has greatly been nourished by experiments with alcohol, heroin, morphine and opium, to the point where these substances have become an integral part of his lifestyle and creative process. Among his various experiences, one moment marked a major turning point in his life – the first time he tried ayahuasca during his trip to South America. This beverage, made from vines of the indigenous Banisteriopsis plant, has the ability to induce a trance-like, mystical experience to its users. The latter experience hallucinatory visions and presences, while their sensory perception is transformed and increased tenfold. According to popular belief, this experience purifies the body. For centuries, this unique state of consciousness inviting dreams into reality has been at the heart of the collective and traditional rituals of the Shipibo-Conibo, an indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon, who use this preparation for ceremonial, spiritual, and therapeutic purposes. Their experiences with ayahuasca have given rise to a fascinating and enigmatic body of artistic work. The exhibition “Shamanic Visions” offers a fascinating insight into the topic until May 24th, 2024, at Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. It also helps bring about a better understanding of these unprecedented forms of spiritual elevation, which have gradually won over Western artists and writers in the age of globalization, and keeps being a source of inspiration today.

From ayahuasca to patterns drawn on textiles and ceramics

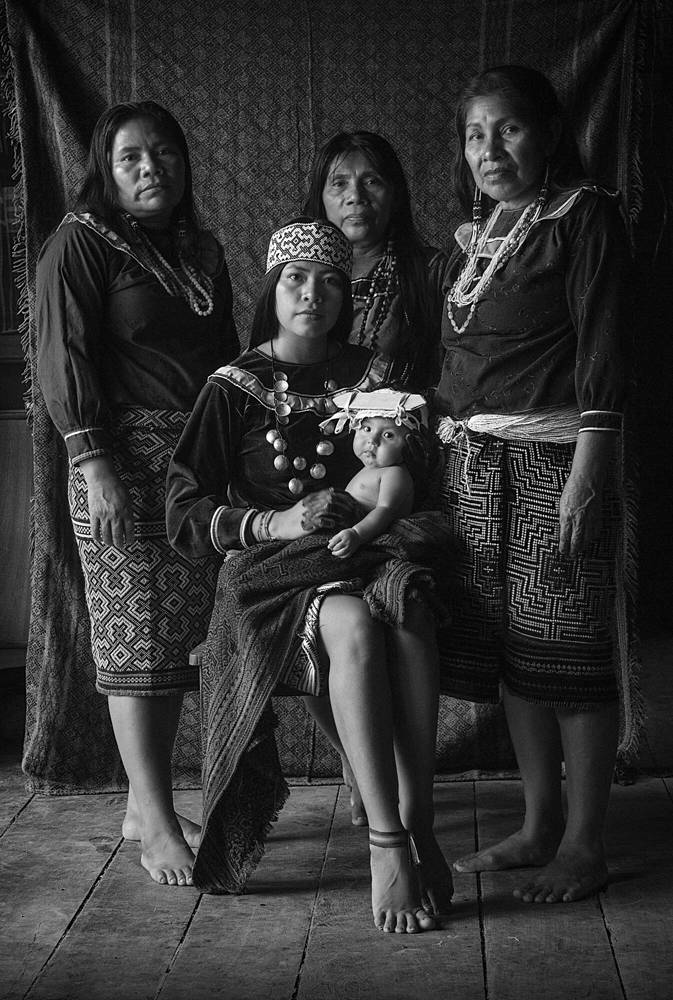

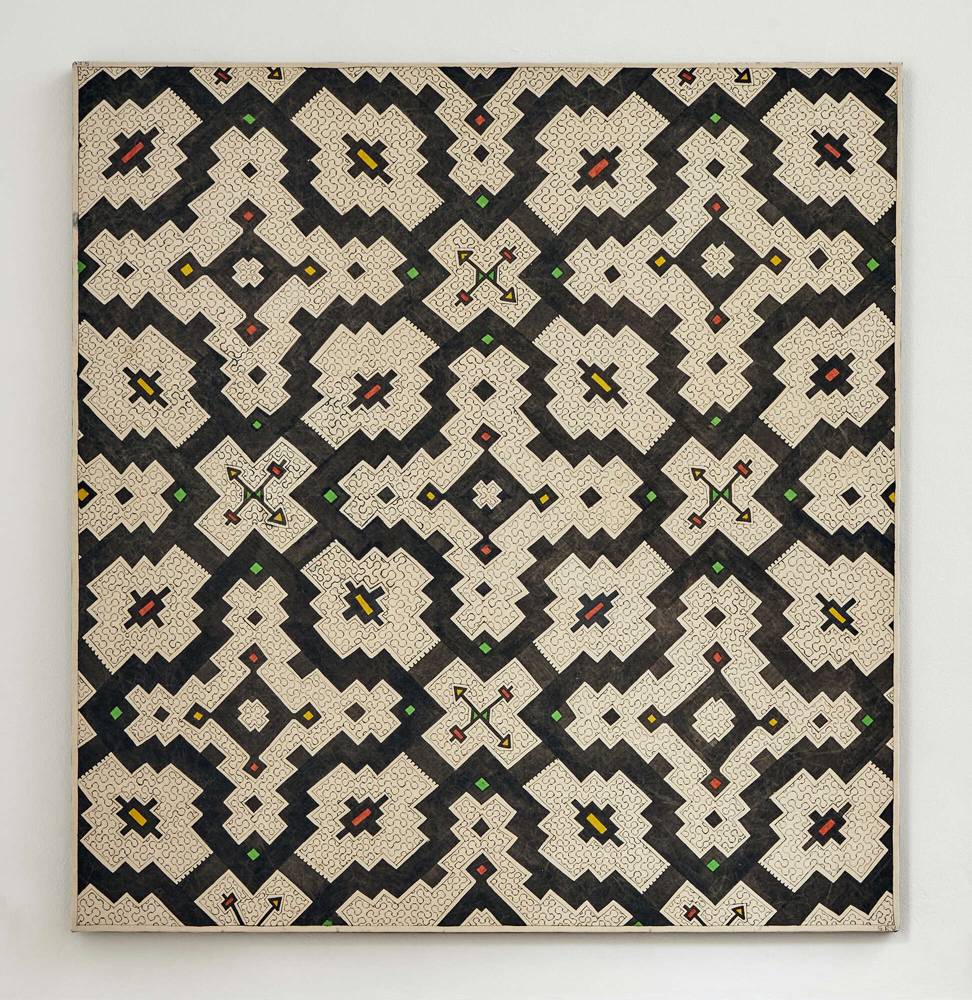

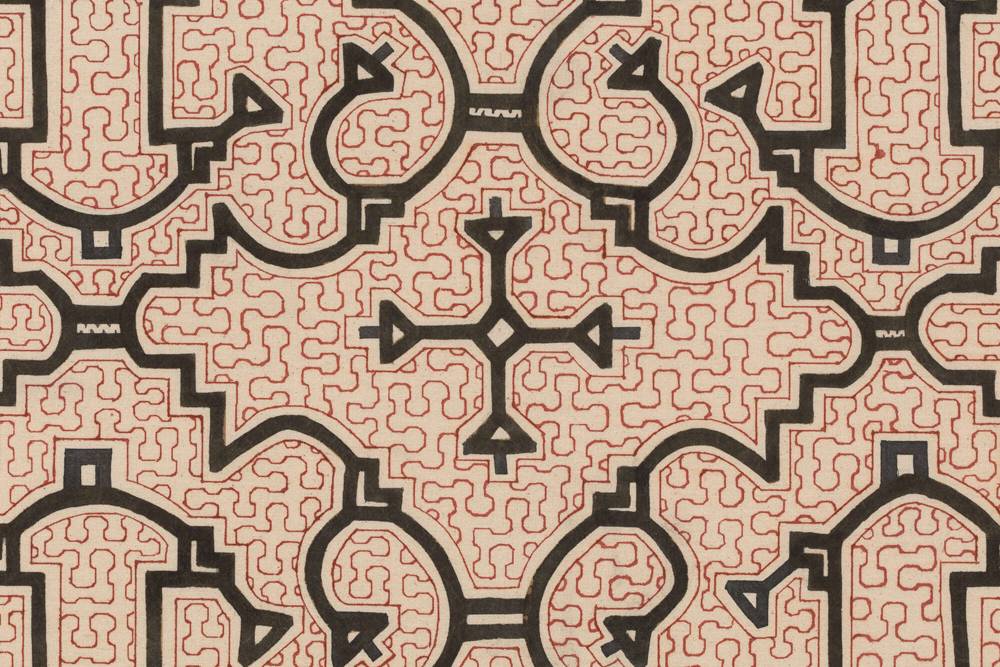

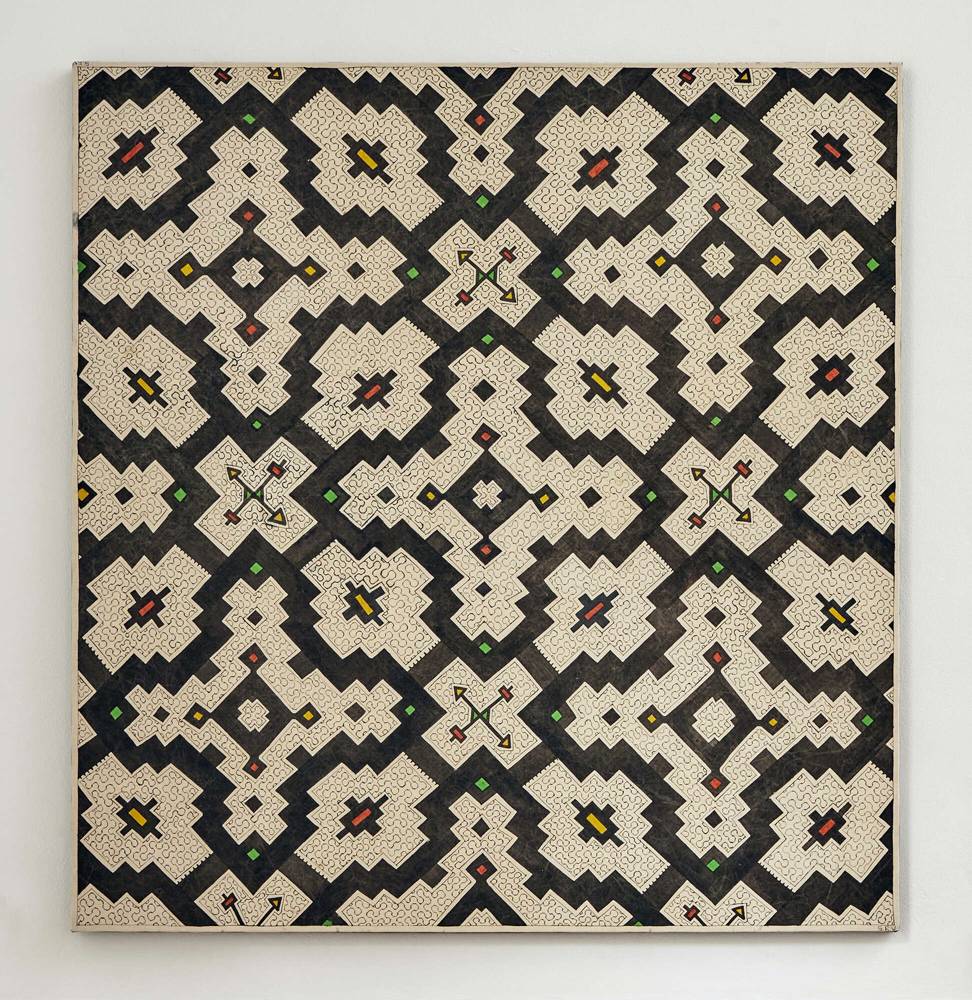

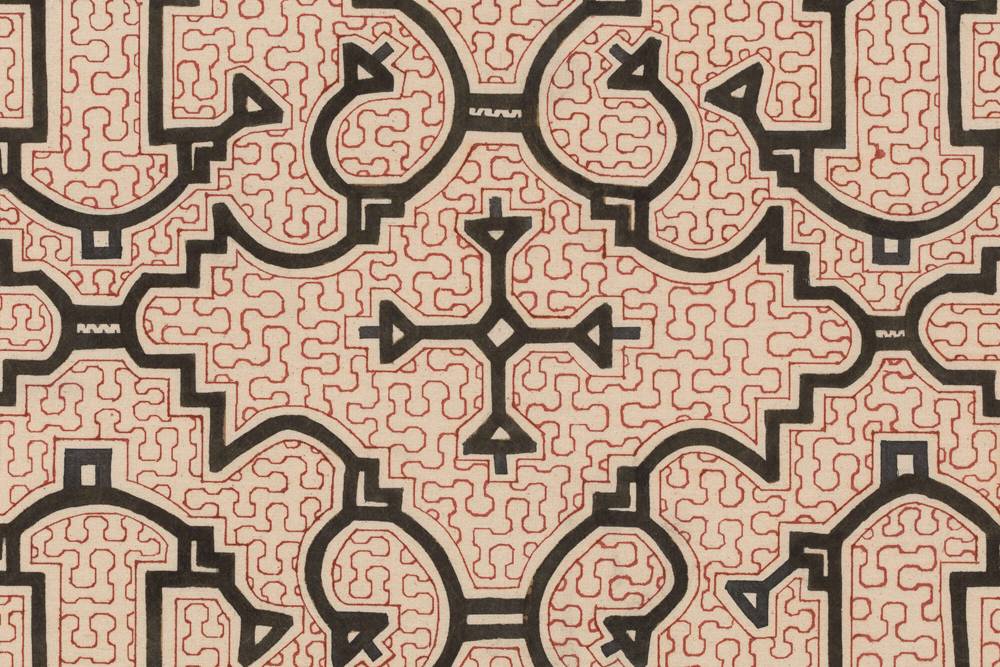

“The ayahuasca vine helps you connect with the invisible”, a Shipibo-Conibo woman explains in a video, as she prepares a pot to cook the plants that will eventually be ingested during collective rituals. While this first cooking usually causes nausea and vomiting, one has to wait for the second cooking to experience the eagerly-awaited visions. The invocation of visions is traditionally accompanied by shamanic chanting. Despite its ‘invisible’ nature, the world encountered during this mystical experience generates precise shapes in most minds – regular, thin, curved, or straight lines, forming crosses, squares, triangles, and other small circles which, when joined together, give birth to some kind of labyrinth… The Shipibo-Conibo have called these patterns ‘Kené’ and have even attributed several meanings to their drawings according to their own beliefs, before attempting to reproduce them themselves – one evokes the wings of birds, while the other represents the spirit of the eye.

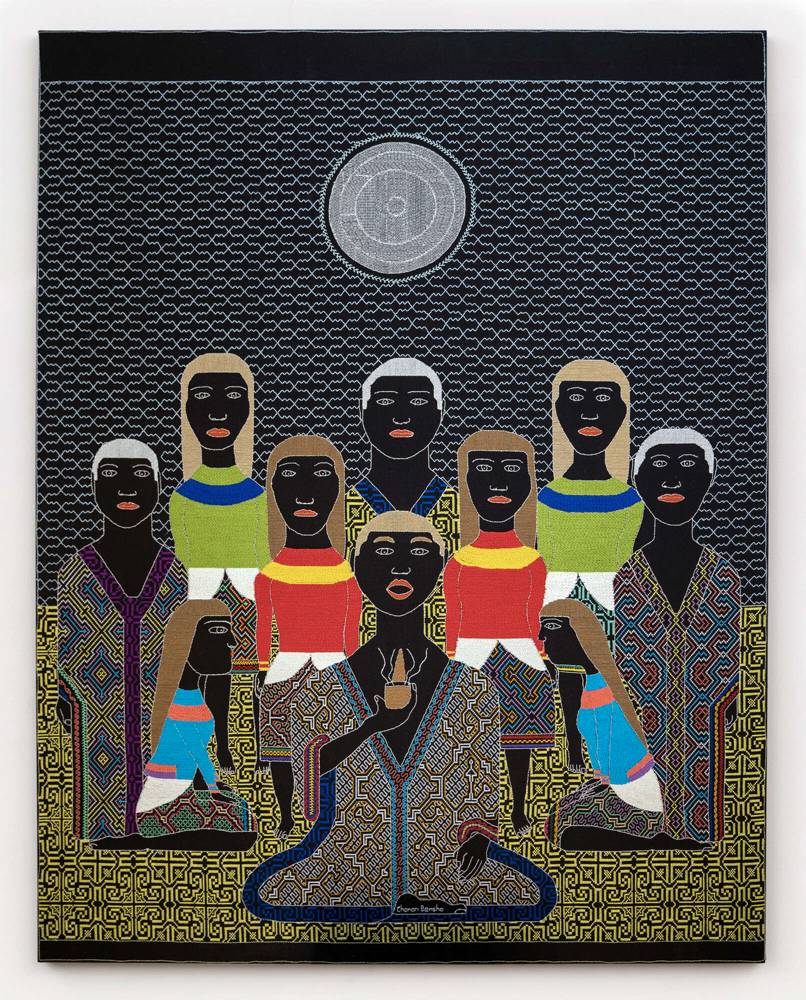

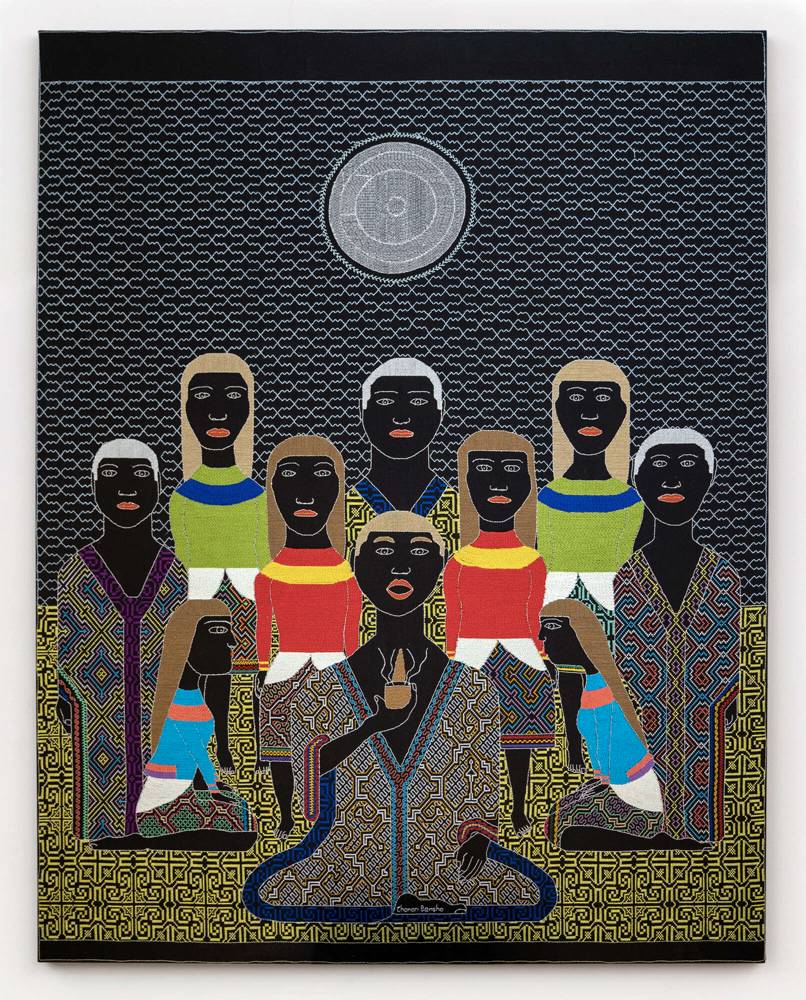

Like other abstract and geometric motifs found in many different civilisations, from the Moucharabieh in Morocco to the Asanoha in Japan, Kené is also the bearer of an age-old history. Painted on textiles or ceramics, the techniques are passed down from one generation to the next, usually from mother to daughter, and are generally a guarantee of protection. The recent works by contemporary indigenous artists featured in the exhibition are proof that ayahuasca has given rise to a creative tradition based on an inner, personal experience, constantly opening the doors to new interpretations. In one of her embroideries on cotton fabric, Shipibo-Conibo artist Chonon Bensho has reinterpreted Botticelli’s Venus with characters from her community and a landscape decorated exclusively with Kené patterns.

En 1990, lorsqu’un journaliste lui demande s’il serait capable de créer sans drogue, l’écrivain William S. Burroughs rétorque spontanément : “Je ne crois pas.” Une réponse éloquente du romancier américain, dont l’œuvre s’est grandement nourrie d’expériences avec l’alcool, l’héroïne, la morphine ou encore l’opium, au point que celles-ci fassent partie intégrante de son mode de vie et de création. Parmi ses nombreuses expériences, l’une a marqué un tournant majeur dans sa vie : celle de l’ayahuasca, testée lors de son voyage en Amérique du Sud. Le breuvage, réalisé à l’aide de lianes de la plante indigène Banisteriopsis, possède en effet la vertu de faire vivre à celui qui l’ingère une expérience mystique proche de la transe. Lui viennent alors des visions et présences hallucinatoires, tandis que la perception sensorielle se trouve transformée et décuplée – autant de bouleversements dont le corps, d’après les croyances, sortira purifié. Depuis plusieurs siècles, cet état si singulier de conscience, qui semble inviter le rêve dans le cadre de la réalité, est au cœur des rites collectifs et traditionnels des Shipibo-Konibos, peuple autochtone de l’Amazonie péruvienne qui utilise cette préparation à des fins cérémonielles, spirituelles et thérapeutiques. De leurs expériences à l’ayahuasca a émergé une production artistique fascinante et énigmatique, dont l’exposition “Visions chamaniques” présente, jusqu’au 26 mai 2024 au musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, un aperçu engageant. Et livre quelques clés pour mieux comprendre ces formes d’élévation de l’esprit inédites, qui a progressivement conquis les artistes et écrivains occidentaux à l’heure de la mondialisation, et continue d’inspirer de nos jours.

De l’ayahuasca aux motifs sur textile et céramique

“La liane de l’ayahuasca permet de se connecter avec l’invisible”, résume en vidéo une femme Shipibo-Konibo, alors en pleine préparation de la marmite dans laquelle elle fera cuire les plantes, ensuite ingérées lors de rites collectifs. Si cette première cuisson provoque habituellement nausées et vomissements, il faudra attendre la deuxième pour connaître les visions tant attendues, dont l’invocation se double traditionnellement de chants chamaniques. Malgré son caractère “invisible”, le monde rencontré lors de cette expérience mystique génère dans la plupart des esprits des formes précises : lignes régulières et serrées, courbes ou droites, formant des croix, carrés, triangles et autres petits ronds qui, ainsi réunis, dessinent une sorte de labyrinthe… Les Shipibo-Konibos ont donné un nom à ces motifs, kené, et leur ont même attribué plusieurs significations selon les dessins d’après leurs propres croyances – l’un évoque les ailes des oiseaux, l’autre l’esprit de l’œil – avant de tenter de les reproduire par eux-mêmes.

À l’instar d’autres dessins abstraits et géométriques rencontrés dans de nombreuses civilisations, entre les moucharabieh au Maroc et les asanoha au Japon, le kené est également porteur d’une histoire séculaire : qu’il soit peint sur le textile ou la céramique, ses techniques sont transmises de génération en génération, la plupart du temps de mère en fille, et sont généralement gages de protection. Les œuvres récentes d’artistes contemporaines indigènes présentées dans l’exposition en attestent : d’une expérience intérieure et personnelle, l’ayahuasca a fait naître une tradition créative, ouvrant sans cesse à de nouvelles relectures. Dans l’une de ses broderies sur coton, l’artiste Shipibo-Konibo Chonon Bensho a par exemple réinterprété la Vénus de Botticelli avec des personnages de sa communauté et un paysage orné exclusivement de motifs kené.

In 1990, when asked by a journalist whether he would be able to create without using any substances, the writer William S. Burroughs spontaneously delivered an eloquent answer: “I don’t think so”. The American novelist’s work has greatly been nourished by experiments with alcohol, heroin, morphine and opium, to the point where these substances have become an integral part of his lifestyle and creative process. Among his various experiences, one moment marked a major turning point in his life – the first time he tried ayahuasca during his trip to South America. This beverage, made from vines of the indigenous Banisteriopsis plant, has the ability to induce a trance-like, mystical experience to its users. The latter experience hallucinatory visions and presences, while their sensory perception is transformed and increased tenfold. According to popular belief, this experience purifies the body. For centuries, this unique state of consciousness inviting dreams into reality has been at the heart of the collective and traditional rituals of the Shipibo-Conibo, an indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon, who use this preparation for ceremonial, spiritual, and therapeutic purposes. Their experiences with ayahuasca have given rise to a fascinating and enigmatic body of artistic work. The exhibition “Shamanic Visions” offers a fascinating insight into the topic until May 24th, 2024, at Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. It also helps bring about a better understanding of these unprecedented forms of spiritual elevation, which have gradually won over Western artists and writers in the age of globalization, and keeps being a source of inspiration today.

From ayahuasca to patterns drawn on textiles and ceramics

“The ayahuasca vine helps you connect with the invisible”, a Shipibo-Conibo woman explains in a video, as she prepares a pot to cook the plants that will eventually be ingested during collective rituals. While this first cooking usually causes nausea and vomiting, one has to wait for the second cooking to experience the eagerly-awaited visions. The invocation of visions is traditionally accompanied by shamanic chanting. Despite its ‘invisible’ nature, the world encountered during this mystical experience generates precise shapes in most minds – regular, thin, curved, or straight lines, forming crosses, squares, triangles, and other small circles which, when joined together, give birth to some kind of labyrinth… The Shipibo-Conibo have called these patterns ‘Kené’ and have even attributed several meanings to their drawings according to their own beliefs, before attempting to reproduce them themselves – one evokes the wings of birds, while the other represents the spirit of the eye.

Like other abstract and geometric motifs found in many different civilisations, from the Moucharabieh in Morocco to the Asanoha in Japan, Kené is also the bearer of an age-old history. Painted on textiles or ceramics, the techniques are passed down from one generation to the next, usually from mother to daughter, and are generally a guarantee of protection. The recent works by contemporary indigenous artists featured in the exhibition are proof that ayahuasca has given rise to a creative tradition based on an inner, personal experience, constantly opening the doors to new interpretations. In one of her embroideries on cotton fabric, Shipibo-Conibo artist Chonon Bensho has reinterpreted Botticelli’s Venus with characters from her community and a landscape decorated exclusively with Kené patterns.

En 1990, lorsqu’un journaliste lui demande s’il serait capable de créer sans drogue, l’écrivain William S. Burroughs rétorque spontanément : “Je ne crois pas.” Une réponse éloquente du romancier américain, dont l’œuvre s’est grandement nourrie d’expériences avec l’alcool, l’héroïne, la morphine ou encore l’opium, au point que celles-ci fassent partie intégrante de son mode de vie et de création. Parmi ses nombreuses expériences, l’une a marqué un tournant majeur dans sa vie : celle de l’ayahuasca, testée lors de son voyage en Amérique du Sud. Le breuvage, réalisé à l’aide de lianes de la plante indigène Banisteriopsis, possède en effet la vertu de faire vivre à celui qui l’ingère une expérience mystique proche de la transe. Lui viennent alors des visions et présences hallucinatoires, tandis que la perception sensorielle se trouve transformée et décuplée – autant de bouleversements dont le corps, d’après les croyances, sortira purifié. Depuis plusieurs siècles, cet état si singulier de conscience, qui semble inviter le rêve dans le cadre de la réalité, est au cœur des rites collectifs et traditionnels des Shipibo-Konibos, peuple autochtone de l’Amazonie péruvienne qui utilise cette préparation à des fins cérémonielles, spirituelles et thérapeutiques. De leurs expériences à l’ayahuasca a émergé une production artistique fascinante et énigmatique, dont l’exposition “Visions chamaniques” présente, jusqu’au 26 mai 2024 au musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, un aperçu engageant. Et livre quelques clés pour mieux comprendre ces formes d’élévation de l’esprit inédites, qui a progressivement conquis les artistes et écrivains occidentaux à l’heure de la mondialisation, et continue d’inspirer de nos jours.

De l’ayahuasca aux motifs sur textile et céramique

“La liane de l’ayahuasca permet de se connecter avec l’invisible”, résume en vidéo une femme Shipibo-Konibo, alors en pleine préparation de la marmite dans laquelle elle fera cuire les plantes, ensuite ingérées lors de rites collectifs. Si cette première cuisson provoque habituellement nausées et vomissements, il faudra attendre la deuxième pour connaître les visions tant attendues, dont l’invocation se double traditionnellement de chants chamaniques. Malgré son caractère “invisible”, le monde rencontré lors de cette expérience mystique génère dans la plupart des esprits des formes précises : lignes régulières et serrées, courbes ou droites, formant des croix, carrés, triangles et autres petits ronds qui, ainsi réunis, dessinent une sorte de labyrinthe… Les Shipibo-Konibos ont donné un nom à ces motifs, kené, et leur ont même attribué plusieurs significations selon les dessins d’après leurs propres croyances – l’un évoque les ailes des oiseaux, l’autre l’esprit de l’œil – avant de tenter de les reproduire par eux-mêmes.

À l’instar d’autres dessins abstraits et géométriques rencontrés dans de nombreuses civilisations, entre les moucharabieh au Maroc et les asanoha au Japon, le kené est également porteur d’une histoire séculaire : qu’il soit peint sur le textile ou la céramique, ses techniques sont transmises de génération en génération, la plupart du temps de mère en fille, et sont généralement gages de protection. Les œuvres récentes d’artistes contemporaines indigènes présentées dans l’exposition en attestent : d’une expérience intérieure et personnelle, l’ayahuasca a fait naître une tradition créative, ouvrant sans cesse à de nouvelles relectures. Dans l’une de ses broderies sur coton, l’artiste Shipibo-Konibo Chonon Bensho a par exemple réinterprété la Vénus de Botticelli avec des personnages de sa communauté et un paysage orné exclusivement de motifs kené.

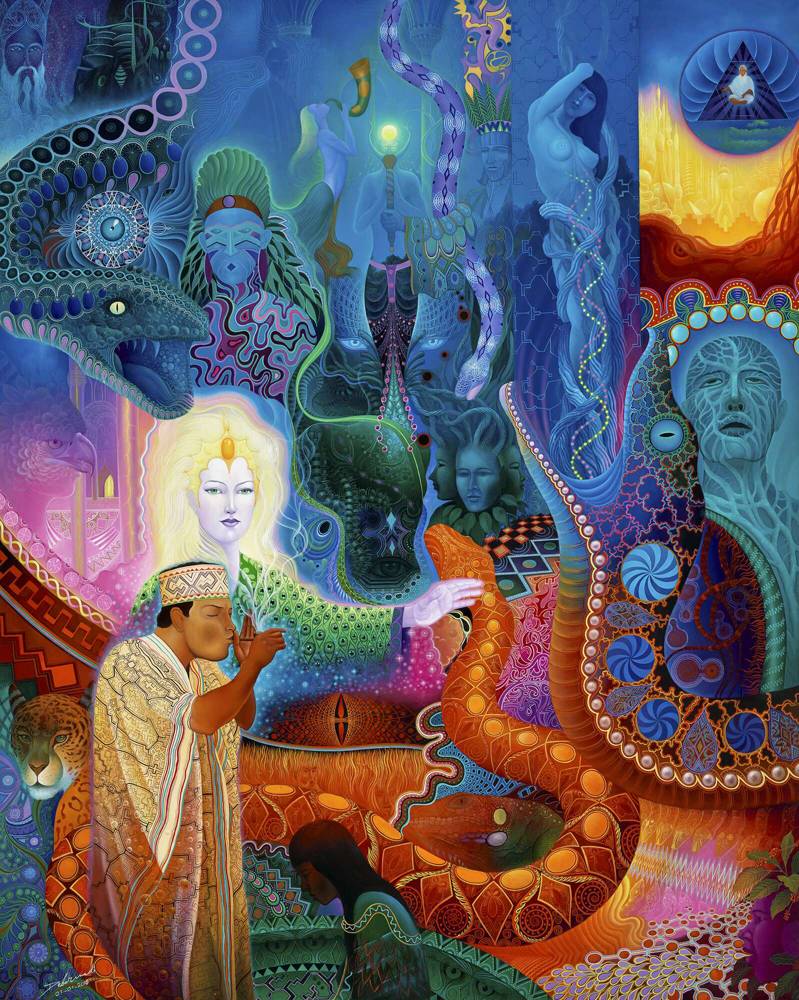

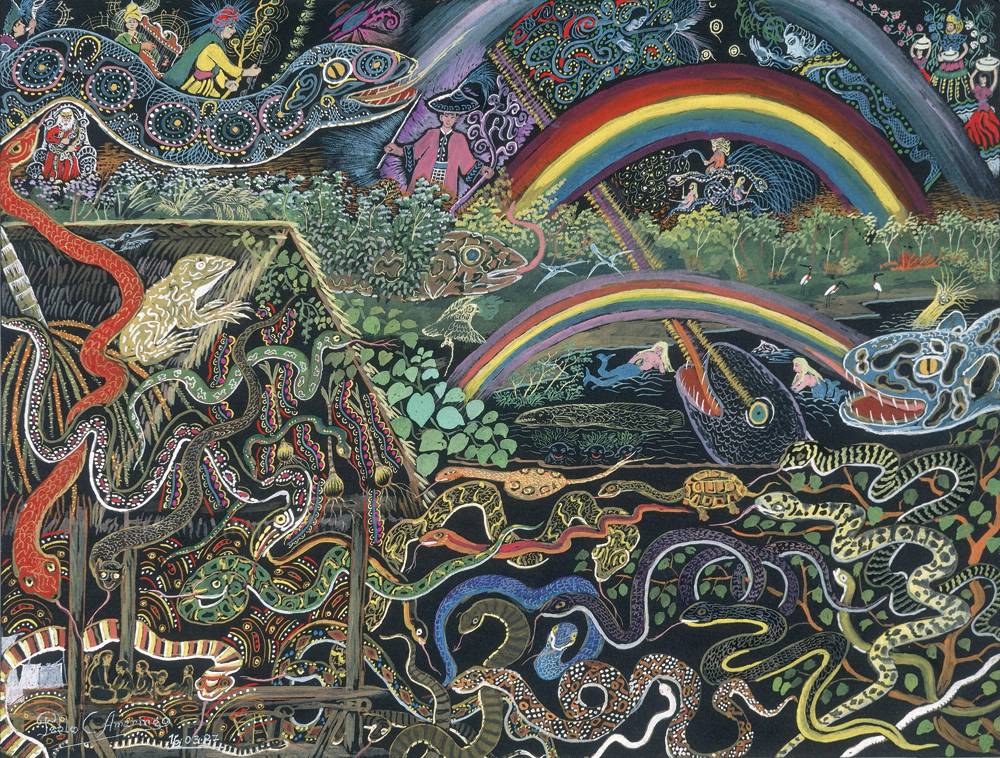

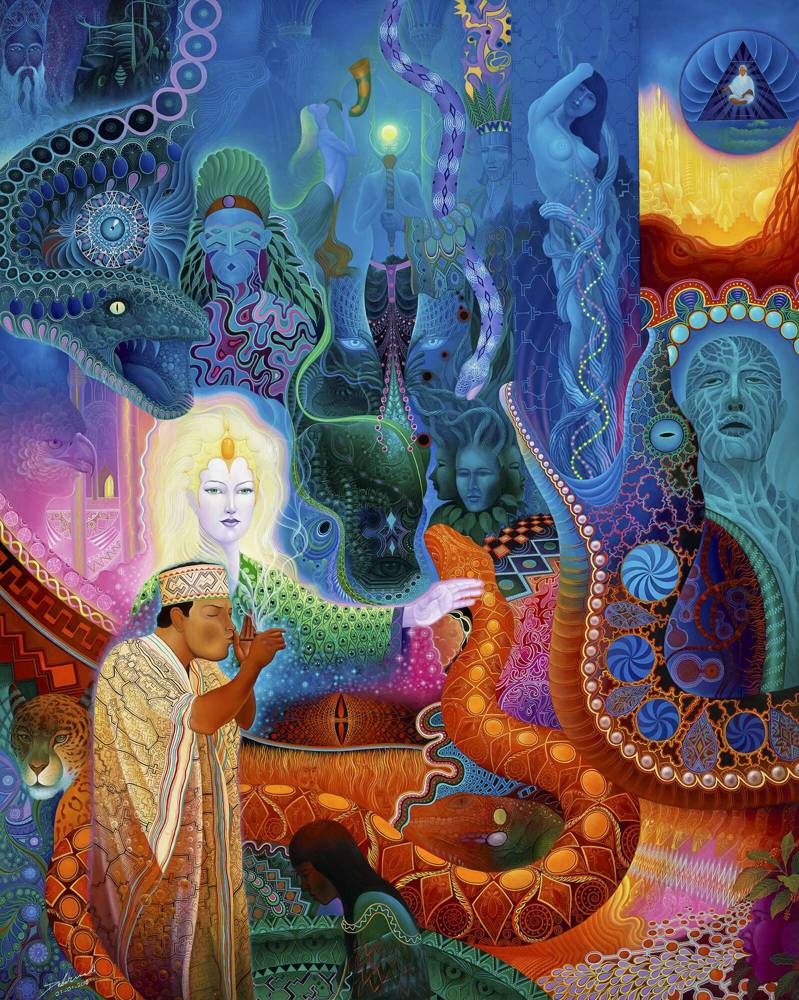

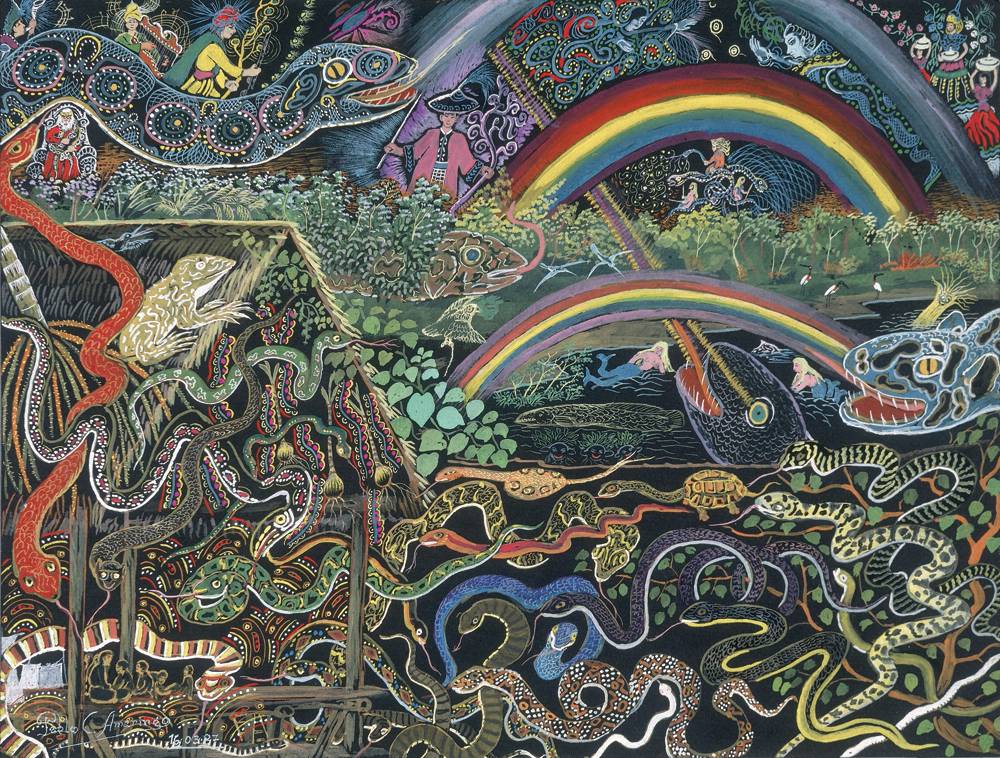

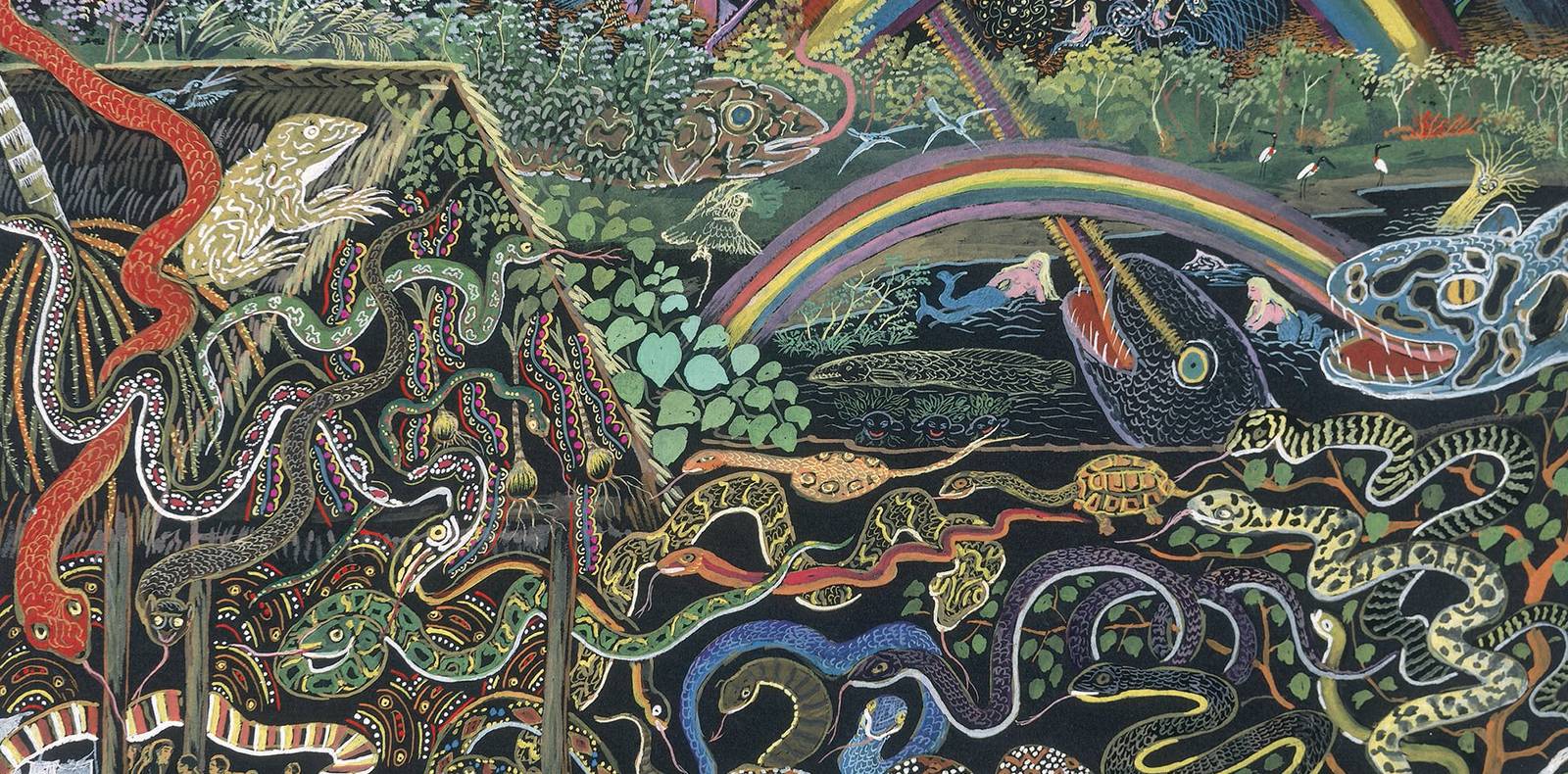

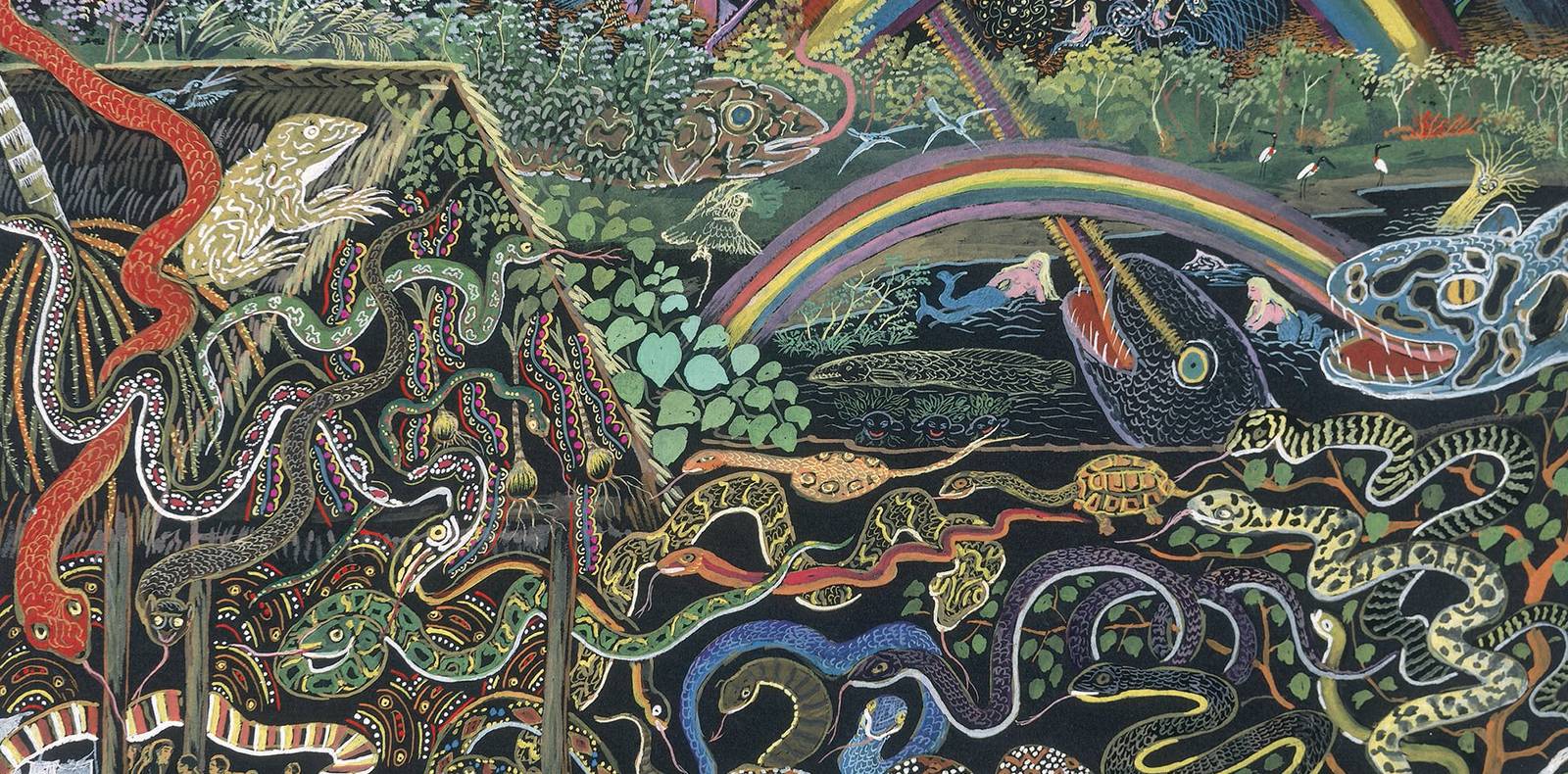

Fascinating works of art celebrating the Amazon

Presented above the museum’s pre-Hispanic and South American collections, the exhibition “Shamanic Visions” reminds us that the artistic angle, nourished by ethnographic and anthropological research into the Shipibo-Conibo community, prevails over a scientific approach that would attempt to study how ayahuasca works and the symptoms it induces. When exploring the exhibition, one is drawn into the dense, colorful paintings of Peruvian artist Pablo Amaringo, with their almost Boschian compositions filled with luxuriant vegetation and fantastic animals. One can also witness the astonishing divine creatures sculpted in wood, then covered in painted motifs, by José Tamani and Jheferson Saldaña, and try to decipher the symbols on the canvases of Roldan Pinedo, another member of the Peruvian community. While a number of recurring elements sheds light on the content of the visions, such as trees, birds and, very often, myriads of snakes, all these works seem to converge towards the same goal. Pablo Amaringo himself clearly expressed it in the 1990s: “to preserve and respect the nature around us”. It is hard not to read a reminder of the current critical situation of the Amazon rainforest, the ‘green lung’ of our planet.

Des œuvres d’art fascinantes qui célèbrent la nature amazonienne

Présentée au-dessus des collections préhispaniques et sud-américaines du musée, l’exposition “Visions chamaniques” nous le rappelle : plutôt qu’une perspective scientifique, qui tâcherait d’étudier le fonctionnement de l’ayahuasca pour en comprendre les symptômes, c’est ici l’angle artistique qui prime, nourri de recherches ethnographiques et anthropologiques sur la communauté Shipibo-Konibo. Au fil de la visite, on plonge ainsi dans les peintures denses et colorées de l’artiste péruvien Pablo Amaringo, compositions presque boschiennes peuplées de végétation luxuriante et d’animaux fantastiques, contourne les étonnantes créatures divines sculptées dans le bois puis recouvertes de peinture et de motifs par José Tamani et Jheferson Saldaña, jusqu’à tenter de décrypter les symboles des toiles de Roldan Pinedo, lui aussi issu de la communauté péruvienne. Si plusieurs éléments récurrents – les arbres, les oiseaux, et très souvent des myriades des serpents – nous éclairent davantage sur le contenu des visions, toutes ces œuvres semblent converger vers un même but, formulé très clairement par Pablo Amaringo lui-même dans les années 90 : “préserver et respecter la nature environnante”. Difficile de ne pas y lire aujourd’hui un rappel de la situation critique de la forêt amazonienne, “poumon vert” de notre planète.

Fascinating works of art celebrating the Amazon

Presented above the museum’s pre-Hispanic and South American collections, the exhibition “Shamanic Visions” reminds us that the artistic angle, nourished by ethnographic and anthropological research into the Shipibo-Conibo community, prevails over a scientific approach that would attempt to study how ayahuasca works and the symptoms it induces. When exploring the exhibition, one is drawn into the dense, colorful paintings of Peruvian artist Pablo Amaringo, with their almost Boschian compositions filled with luxuriant vegetation and fantastic animals. One can also witness the astonishing divine creatures sculpted in wood, then covered in painted motifs, by José Tamani and Jheferson Saldaña, and try to decipher the symbols on the canvases of Roldan Pinedo, another member of the Peruvian community. While a number of recurring elements sheds light on the content of the visions, such as trees, birds and, very often, myriads of snakes, all these works seem to converge towards the same goal. Pablo Amaringo himself clearly expressed it in the 1990s: “to preserve and respect the nature around us”. It is hard not to read a reminder of the current critical situation of the Amazon rainforest, the ‘green lung’ of our planet.

Des œuvres d’art fascinantes qui célèbrent la nature amazonienne

Présentée au-dessus des collections préhispaniques et sud-américaines du musée, l’exposition “Visions chamaniques” nous le rappelle : plutôt qu’une perspective scientifique, qui tâcherait d’étudier le fonctionnement de l’ayahuasca pour en comprendre les symptômes, c’est ici l’angle artistique qui prime, nourri de recherches ethnographiques et anthropologiques sur la communauté Shipibo-Konibo. Au fil de la visite, on plonge ainsi dans les peintures denses et colorées de l’artiste péruvien Pablo Amaringo, compositions presque boschiennes peuplées de végétation luxuriante et d’animaux fantastiques, contourne les étonnantes créatures divines sculptées dans le bois puis recouvertes de peinture et de motifs par José Tamani et Jheferson Saldaña, jusqu’à tenter de décrypter les symboles des toiles de Roldan Pinedo, lui aussi issu de la communauté péruvienne. Si plusieurs éléments récurrents – les arbres, les oiseaux, et très souvent des myriades des serpents – nous éclairent davantage sur le contenu des visions, toutes ces œuvres semblent converger vers un même but, formulé très clairement par Pablo Amaringo lui-même dans les années 90 : “préserver et respecter la nature environnante”. Difficile de ne pas y lire aujourd’hui un rappel de la situation critique de la forêt amazonienne, “poumon vert” de notre planète.

Shamanic visions are spreading from the Amazon to Western countries

It was only a matter of time before these transcendent experiences found a resonance outside the Amazon. As the exhibition shows, the international diffusion of ayahuasca experiences reflects the history of the Western domination in the Americas, from the colonial exploitation of the Amazon in the 19th century to the development of “shamanic tourism” from the mid-20th century onwards. Writers were openly fascinated by these experiences. While the names of William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Aldous Huxley stand out in the exhibition, it is hard not to think of Charles Baudelaire’s 1860 collection Paradis Artificiels (Artificial Paradises), in which the poet already described both the creative benefits and dangers of hashish, or Henri Michaux’s Miserable Miracle (1956), a collection of texts and drawings produced by the artist under the influence of mescaline. All these Western authors have demonstrated in their own way that, while psychotropic and hallucinogenic substances can indeed open the door to another world and nourish the imagination, their qualities are quickly overtaken by the many dangers associated with their use, which is very different from the Shipibo-Conibos’s ancient healing and divination at the core of the community’s mythology and philosophy.

The Western perspective and conception of art is so distinct from that of the indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon that it will probably never be able to provide a true understanding of the Shipibo-Conibo creations born of ayahuasca. Beyond their undeniable artistic qualities, the artworks displayed in the exhibition barely succeed in accurately transcribing the experience. However, at the end of the exhibition, French filmmaker Jan Kounen sets out to meet this challenge through virtual reality, taking visitors on a fifteen-minute hallucinatory journey. The 360° journey through snake jaws, arachnid baths, cathedral-like rose windows, and other ossuaries is a praiseworthy attempt to have a better understanding of this occult world. Yet, the unisensory and inevitably individual experience of ayahuasca, here deprived of the direct connection to nature, smells, or human interactions, keeps us a long way from total immersion. And so much the better… in order to retain its exceptional power, ayahuasca cannot give up all its secrets so easily.

“Shamanic visions. Ayahuasca arts in the Peruvian Amazon”, from November 14th, 2023 to May 26th, 2024 at Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 7th arrondissement.

Translation by Emma Naroumbo Armaing.

De l’Amazonie à l’Occident, les visions chamaniques se répandent

Il n’était qu’une question de temps avant que ces expériences transcendantes sortent de l’Amazonie. L’exposition le montre bien : l’expansion internationale des expériences à l’ayahuasca reflète l’histoire de la domination occidentale sur les Amériques, de l’exploitation coloniale de l’Amazonie au 19e siècle au développement du “tourisme chamanique” à partir de la moitié du 20e. Alors que l’on croise au musée les noms de William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg ou encore Aldous Huxley, écrivains ouvertement fascinés par ces expériences, difficile de ne pas penser également aux Paradis Artificiels (1860) de Charles Baudelaire, où le poète décrivait déjà les effets créatifs du haschich que ses dangers, ou encore au Misérable Miracle (1956) de Henri Michaux, recueil de textes et de dessins réalisés par l’artiste sous l’emprise de la mescaline. Tous ces auteurs occidentaux l’ont démontré à leur manière : si les substances psychotropes et hallucinogènes peuvent, en effet, ouvrir la porte d’un autre monde et nourrir l’imaginaire, leurs qualités seront bien vite rattrapées par les nombreux dangers relevés quant à leur consommation, bien différente des rites séculaires de guérison et de divination des Shipibo-Konibos, au cœur même de la mythologie et de la philosophie de la communauté.

Il n’est pas certain que le prisme occidental, et sa conception de l’œuvre d’art bien distincte de celle des autochtones d’Amazonie péruvienne, permette un jour de comprendre véritablement les créations Shipibo-Konibos nées de l’ayahuasca. Ni que les pièces présentées dans l’exposition, au-delà de leurs incontestables qualités artistiques, ne parviennent à retranscrire précisément son expérience. En clôture de l’exposition, toutefois, le cinéaste français Jan Kounen cherche à relever ce défi grâce à la réalité virtuelle, en invitant dans un voyage hallucinatoire d’une quinzaine de minutes. Le parcours à 360°, traversant des mâchoires de serpents, bains d’arachnides, rosaces aux airs de cathédrales et autres ossuaires, offre une tentative louable de mieux comprendre ce monde occulte, bien que son expérience unisensorielle et inévitablement individuelle, privée de la connexion directe la nature, des odeurs ou encore des interactions humaines, nous tienne bien loin de l’immersion totale. Et tant mieux : afin de conserver son pouvoir exceptionnel, l’ayahuasca ne peut livrer si facilement tous ses secrets.

“Visions chamaniques. Arts de l’ayahuasca en Amazonie péruvienne”, du 14 novembre 2023 au 26 mai 2024 au musée du Quai Branly, Paris 7e.

Shamanic visions are spreading from the Amazon to Western countries

It was only a matter of time before these transcendent experiences found a resonance outside the Amazon. As the exhibition shows, the international diffusion of ayahuasca experiences reflects the history of the Western domination in the Americas, from the colonial exploitation of the Amazon in the 19th century to the development of “shamanic tourism” from the mid-20th century onwards. Writers were openly fascinated by these experiences. While the names of William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Aldous Huxley stand out in the exhibition, it is hard not to think of Charles Baudelaire’s 1860 collection Paradis Artificiels (Artificial Paradises), in which the poet already described both the creative benefits and dangers of hashish, or Henri Michaux’s Miserable Miracle (1956), a collection of texts and drawings produced by the artist under the influence of mescaline. All these Western authors have demonstrated in their own way that, while psychotropic and hallucinogenic substances can indeed open the door to another world and nourish the imagination, their qualities are quickly overtaken by the many dangers associated with their use, which is very different from the Shipibo-Conibos’s ancient healing and divination at the core of the community’s mythology and philosophy.

The Western perspective and conception of art is so distinct from that of the indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon that it will probably never be able to provide a true understanding of the Shipibo-Conibo creations born of ayahuasca. Beyond their undeniable artistic qualities, the artworks displayed in the exhibition barely succeed in accurately transcribing the experience. However, at the end of the exhibition, French filmmaker Jan Kounen sets out to meet this challenge through virtual reality, taking visitors on a fifteen-minute hallucinatory journey. The 360° journey through snake jaws, arachnid baths, cathedral-like rose windows, and other ossuaries is a praiseworthy attempt to have a better understanding of this occult world. Yet, the unisensory and inevitably individual experience of ayahuasca, here deprived of the direct connection to nature, smells, or human interactions, keeps us a long way from total immersion. And so much the better… in order to retain its exceptional power, ayahuasca cannot give up all its secrets so easily.

“Shamanic visions. Ayahuasca arts in the Peruvian Amazon”, from November 14th, 2023 to May 26th, 2024 at Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 7th arrondissement.

Translation by Emma Naroumbo Armaing.

De l’Amazonie à l’Occident, les visions chamaniques se répandent

Il n’était qu’une question de temps avant que ces expériences transcendantes sortent de l’Amazonie. L’exposition le montre bien : l’expansion internationale des expériences à l’ayahuasca reflète l’histoire de la domination occidentale sur les Amériques, de l’exploitation coloniale de l’Amazonie au 19e siècle au développement du “tourisme chamanique” à partir de la moitié du 20e. Alors que l’on croise au musée les noms de William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg ou encore Aldous Huxley, écrivains ouvertement fascinés par ces expériences, difficile de ne pas penser également aux Paradis Artificiels (1860) de Charles Baudelaire, où le poète décrivait déjà les effets créatifs du haschich que ses dangers, ou encore au Misérable Miracle (1956) de Henri Michaux, recueil de textes et de dessins réalisés par l’artiste sous l’emprise de la mescaline. Tous ces auteurs occidentaux l’ont démontré à leur manière : si les substances psychotropes et hallucinogènes peuvent, en effet, ouvrir la porte d’un autre monde et nourrir l’imaginaire, leurs qualités seront bien vite rattrapées par les nombreux dangers relevés quant à leur consommation, bien différente des rites séculaires de guérison et de divination des Shipibo-Konibos, au cœur même de la mythologie et de la philosophie de la communauté.

Il n’est pas certain que le prisme occidental, et sa conception de l’œuvre d’art bien distincte de celle des autochtones d’Amazonie péruvienne, permette un jour de comprendre véritablement les créations Shipibo-Konibos nées de l’ayahuasca. Ni que les pièces présentées dans l’exposition, au-delà de leurs incontestables qualités artistiques, ne parviennent à retranscrire précisément son expérience. En clôture de l’exposition, toutefois, le cinéaste français Jan Kounen cherche à relever ce défi grâce à la réalité virtuelle, en invitant dans un voyage hallucinatoire d’une quinzaine de minutes. Le parcours à 360°, traversant des mâchoires de serpents, bains d’arachnides, rosaces aux airs de cathédrales et autres ossuaires, offre une tentative louable de mieux comprendre ce monde occulte, bien que son expérience unisensorielle et inévitablement individuelle, privée de la connexion directe la nature, des odeurs ou encore des interactions humaines, nous tienne bien loin de l’immersion totale. Et tant mieux : afin de conserver son pouvoir exceptionnel, l’ayahuasca ne peut livrer si facilement tous ses secrets.

“Visions chamaniques. Arts de l’ayahuasca en Amazonie péruvienne”, du 14 novembre 2023 au 26 mai 2024 au musée du Quai Branly, Paris 7e.