25

25

Albert Oehlen, le peintre de la pop culture exposé au Palazzo Grassi de Venise

Telles des partitions de free-jazz, ses toiles associent, dans un tourbillon de références, symboles de la pop culture, éléments figuratifs et abstraits, dans un chaos surmaîtrisé. Le palais de François Pinault, à Venise, célèbre cet artiste allemand influencé par Sigmar Polke.

Par Thibaut Wychowanok,

Publié le 25 juillet 2018. Modifié le 18 avril 2025.

After Sigmar Polke in 2016, François Pinault is once again offering his Venetian palazzo to a German painter. For the past few months Albert Oehlen, 63, has been installed at the Palazzo Grassi, where over 80 of his canvases are on show until Januar y 2019 in an exhibition put on with the help of curator Caroline Bourgeois. Yet Oehlen is much less well known than Polke, among the general public at any rate. In France he’s only had two big institutional shows: in 2009 at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, and in 2002 in Strasbourg (even if the Villa Arson was showing him as early as 1994). But in 2015, when New York put on a big exhibition at the New Museum, an “Oehlen moment” seemed to be crystallizing. In March 2017, his Selbstporträt mit Palette [Self-Portrait with Palette] went for £2,965,000 at Christie’s London (about e3,365,000), doubling his previous record. The famous dealer Joseph Nahmad gave him an exhibition in November 2017, while his German gallery Max Hetzler followed up in March by showing new works and is planning another show in its Paris space this autumn. Need we add that Oehlen is also now a member of the Gagosian stable?

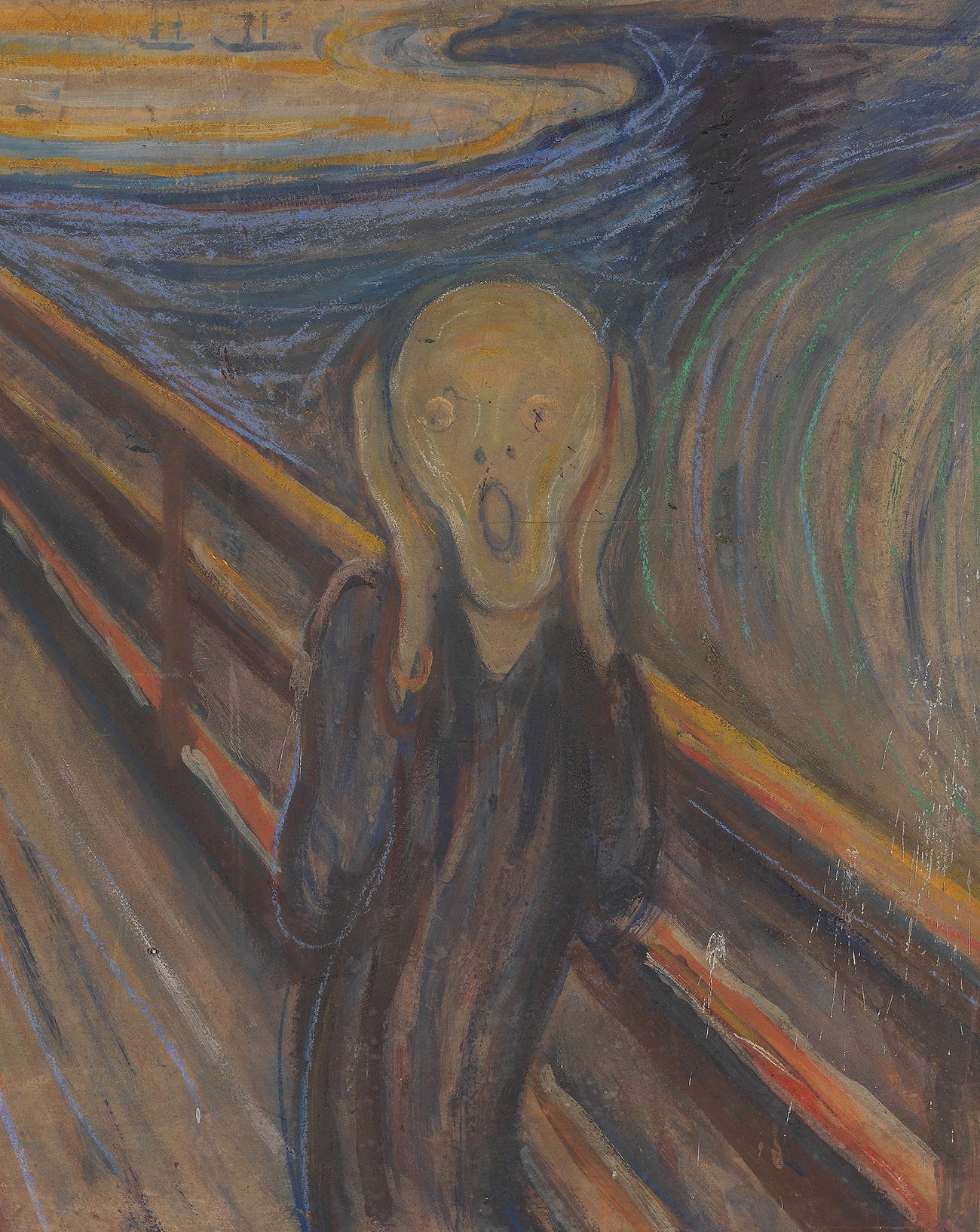

None of which has stopped him from being presented as a true punk. But looking closely at his canvases, it’s less a 70s-style rebellion than a well-mastered Postmodernity that meets the eye. His painting borrows from all over the place, going from one style to another: post-Pop, post-figuration, post-abstraction, post-new technology… One thinks of Polke, of course, who was his teacher, of Willem De Kooning, of Martin Kippenberger, who was his friend, of Brice Marden – a whole stratum of 20th-century painting is reconfigured in his hands.

Oehlen is still producing a whirlwind of disparate and colourful images, as though he were some compulsive-obsessive of deformation, reformation and reinvention of painting, both of its limits and also of its methods.

In the 80s, Oehlen became known for his corrosive figurative pictures like the famous Gegen den Liberalismus [Against Liberalism] (1980) – an ass at the top of a hill. (The guy certainly has a sense of humour.) Then his paintings became more abstract (although he prefers to use the term “post-non-figuration”) forming violent colour compositions with strokes, messy traces, and flat areas of saturation. In 1992 he changed tack again, moving on into the digital for his Computer Paintings which featured repetitive, pixelated black lines and forms, rather reminiscent of the Minitel. In 1997 he made his series of grey paintings; then came the Trees, restricted to black and one other colour on a white background. But then colour was allowed its way again, such as in his large Pop collages and montages from 2009 –10 which mixed logos and household products. Today Oehlen is still producing a whirlwind of disparate and colourful images, as though he were some compulsive-obsessive of deformation, reformation and reinvention of painting, both of its limits and also of its methods.

With Oehlen it’s always a question of being over the top, of rules being immediately broken, of over-controlled chaos. Beyond that, the work seems irreducible to any description or categorization. The Palazzo Grassi show doesn’t take the risk of trying and instead prefers, more aptly, to mix periods. Oehlen’s painting consequently appears even more rootless and timeless, his Pop montages seeming as though they could have been done in the 80s, his recent Conductions from the 2010s recalling his Computer Paintings of the 90s. Behind the apparent chaos, everything is tightly mastered, all references seemingly cut off from their roots and taken out of context. Originally incompatible, they mix in Oehlen’s work to become nothing more than a surface – the impression of a spectacle of pure forms is what dominates. At the exhibition opening, Oehlen put on a performance with an actor playing himself and painting “in the manner of Oehlen” in the atrium of the Palazzo Grassi, which had been transformed into a temporary studio. The real Oehlen was there too, laughing heartily at the actor’s belching. Everything is thus pure construction. Everything is vain. This ironic distance seems to mark the limits of his painting; we may be temporarily fascinated, but are we moved?

Passionate about free jazz, but also electronic music, grunge or indie rock, Oehlen composes his canvases like musical scores.

The hang steps in here, for it perfectly brings out the work’s principal quality – its musicality. Passionate about free jazz, but also electronic music (Plastikman), grunge (the Melvins) or indie rock (Dirty Projectors, Deerhoof), Oehlen composes his canvases like musical scores. A note or a motif recurs time and again in pictures from the same series, while improvisations attempt to derail the monotony that comes from this multiplication. Indeed the whole exhibition forms a great big free-jazz score in and of itself. Motifs can be found from one space to the next, but each time with nuances, improvisations or changes that are almost imperceptible in the general tempo, like infinite variations on a base motif or a techno track whose tiny changes in throbbing rhythm can only be felt physically in a state of trance while on MDMA. In the absence of drugs, the hang at the Palazzo Grassi show might just bring you that high.

Cows by the Water – Albert Oehlen, Palazzo Grassi, until 6 January 2019. www.palazzograssi.it

Après Sigmar Polke en 2016, François Pinault offre à nouveau son palais vénitien à un peintre allemand. Depuis plusieurs mois, Albert Oehlen, 63 ans, a pris possession du Palazzo Grassi : plus de 80 de ses toiles y sont visibles jusqu’en janvier 2019, au sein d’une exposition orchestrée avec la commissaire Caroline Bourgeois. L’artiste est pourtant loin d’avoir la notoriété d’un Polke pour le grand public. En France, on ne lui connaît que deux grandes expositions institutionnelles : en 2009 au musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, et en 2002 à Strasbourg (même si la Villa Arson le présente dès 1994). Mais lorsqu’en 2015 New York accueille une grande exposition au New Museum, un “moment Oehlen” semble se dessiner. En mars 2017, Christie’s Londres adjuge son Selbstporträt mit Palette [Autoportrait avec palette] à 2,965,000 livres [environ 3 365 000 euros], doublant le précédent record de l’artiste. Le célèbre marchand Joseph Nahmad lui consacre également une exposition en novembre 2017. Lui emboîtant le pas, sa galerie allemande Max Hetzler présentait (en mars) de nouvelles œuvres, préfigurant une autre exposition, dans son antenne parisienne, prévue à la rentrée. Le peintre sera au même moment l’invité de la galerie Gagosian à Paris.

Tout cela n’empêche pas Albert Oehlen d’être considéré comme un vrai punk. À bien regarder ses toiles, c’est moins une rébellion seventies qu’une postmodernité bien comprise qui saute aux yeux. Sa peinture multiplie les emprunts et les références, passant d’un style à un autre : post-pop, post-figuration, postabstraction, post-nouvelles technologies… On pense à Polke évidemment, dont il a été l’élève, à Willem De Kooning, à Martin Kippenberger dont il a été l’ami, à Brice Marden… Tout un pan de la peinture du XXe siècle se reconfigure entre ses mains.

Oehlen produit un tourbillon d’images hétéroclites et bigarrées, tel un obsédé compulsif de la déformation, de la reformation et de la réinvention de la peinture, de ses limites et de ses méthodes.

Dès les années 80, Oehlen se fait ainsi connaître avec des toiles figuratives corrosives dont son célèbre Gegen den Liberalismus [Contre le libéralisme] (1980) – un cheval de bois sur une colline. Le garçon a de l’humour. Puis ses peintures se font plus abstraites – lui préfère le terme de “post-non-figuration”. Elles forment de violentes compositions de couleurs : traits, traces brouillonnes, aplats… En 1992, nouveau renversement, Oehlen a recours à l’ordinateur pour ses Computer Paintings : lignes et formes noires répétitives et pixellisées. On pense au Minitel. En 1997, ce sera la série des tableaux gris. Puis, dans la série des Trees [Arbres], il se cantonne au noir combiné à une autre couleur sur fond blanc. Ailleurs, la couleur se fait bien présente, comme sur ses collages ou montages pop de 2009-2010 qui mêlent logos et produits de grande consommation. Oehlen produit, encore et encore, un tourbillon d’images hétéroclites et bigarrées, tel un obsédé compulsif de la déformation, de la reformation et de la réinvention de la peinture, de ses limites et de ses méthodes.

Tout est toujours question de démesure, de règles aussitôt brisées par les déraillements grandiloquents de l’artiste, de chaos surmaîtrisé. L’œuvre semble irréductible à toute description ou catégorisation. De fait, l’exposition du Palazzo Grassi ne s’y risque pas, et préfère, plus justement, entremêler les périodes. Sa peinture apparaît d’autant plus déracinée, hors du temps. Ses montages pop pourraient tout aussi bien avoir été réalisés dans les années 80. Ses récentes Conduction des années 2010 rappellent ses Computer Paintings des années 90. Derrière le chaos apparent, tout est excessivement contrôlé. Toutes les références semblent déracinées, sorties de leur contexte. Incompatibles entre elles à l’origine, elles se mêlent finalement sur la toile d’Oehlen pour n’être plus qu’une surface. Une impression de spectacle de pure forme domine. Lors du vernissage de son exposition, le peintre a mis en scène une performance : un acteur jouant le rôle de l’artiste. Au sein de l’atrium du Palazzo Grassi, transformé pour quelques heures en atelier, il peint “à la manière d’Oehlen”. Le vrai Oehlen est présent, cette mascarade et les éructations de l’acteur le font rire. Tout ne serait donc que pure construction. Tout serait vain. Cette distance ironique forme sans doute la limite de sa peinture. Le spectateur peut être un temps fasciné, mais est-il touché ?

Passionné de free-jazz, mais aussi de musiques électroniques, de grunge ou de rock indé, l’artiste compose ses toiles comme des partitions.

Il le sera plus certainement par un accrochage qui exprime parfaitement la qualité première de l’œuvre : sa musicalité. Passionné de free-jazz, mais aussi de musiques électroniques (Plastikman), de grunge (les Melvins) ou de rock indé (Dirty Projectors, Deerhoof), l’artiste compose ses toiles comme des partitions. Une note ou un refrain revient sans cesse au sein des toiles d’une même série. Des improvisations tentent de faire dérailler la monotonie issue de cette multiplication. Toute l’exposition forme ellemême une grande partition de free-jazz. Les motifs reviennent d’une salle à l’autre, avec des nuances : improvisations ou changements presque imperceptibles du tempo. Comme d’infinies variations à partir d’un motif de base. Comme une boucle en loop. Comme un morceau de techno au rythme lancinant, dont les variations infimes ne résonnent que dans les corps en transe sous MDMA. Justement, au Palazzo Grassi, l’accrochage pourrait bien provoquer cette “montée”.

Exposition Cows by the Water d’Albert Oehlen au Palazzo Grassi à Venise, jusqu’au 6 janvier 2019, www.palazzograssi.it

Exposition d’Albert Oehlen à la galerie Max Hetzler, 57, rue du Temple, Paris IVe , du 13 octobre au 24 novembre.