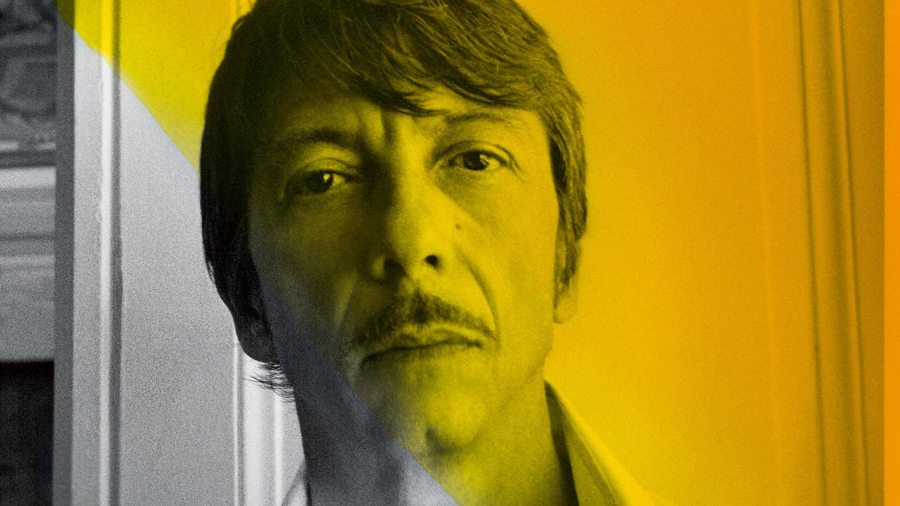

Numéro: You’re now going solo after having been part of a duo, with Maria Grazia Chiuri, for over 20 years. How does this change your work?

Pierpaolo Piccioli: Everything becomes more intuitive, more emotional. When you work with another person, you talk, you have to reach a consensus, so everything is more thoughtful in a way. When I work alone, everything is more direct. I’ve come to realize that I start every collection with a personal reflection about the times in which we live, instead of an inspiration. So for the last couture collection I was thinking about how nowadays everything is so digital and technological. I wanted to get beyond that, to find something spiritual, something sacred. I always have in my mind both the beginning and the final picture. So I have to work towards that picture.

A lot of novelists work that way.

Yes – you have the first page and the last page, and then you have to write all the lines in between, keeping coherence throughout.

Are you very influenced by what you read and see around you?

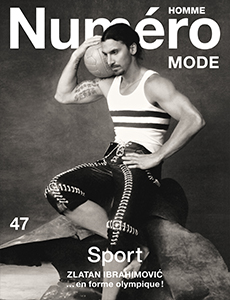

Yes, everything can be inspiring, but I don’t like to be inspired by surfaces: it’s more about the feeling I get from something, the reflexion it triggers inside me. I don’t like to translate anything literally. And sometimes the further it is from your world, the more interesting it is. You have to digest it and redeliver it as something different. For example, for my last menswear collection I looked to the Memphis group, which is not a reference I particularly liked to begin with. What I appreciate about this moment in Italian culture is that it’s when Italy started to work with people from other parts of the world – from Africa or Brazil. It’s an expression of tolerance. I learned a lot about what Memphis did, and also about how they did it, how they got to that point.

I read that another inspiration was Jungian psychology.

I’d just read a book by Jung, and I was very interested in this idea that when you’re born you’re not aware of yourself, you’re part of a group, your family. Then when you grow up you build self-awareness, and afterwards you reintegrate into the group, but with your own vision and identity. It made me think of the importance of social media today: how do you build this identity when the group you’re part of is the huge mass of internet users? And so I started thinking about intimacy and collectiveness. I ended up with this tech-savvy sportswear that was laced with the memories of different ethnicities. It wasn’t that I wanted to talk about African or Indian folks, the idea was simply to say that each one of us has his or her own memory. And it’s interesting when you get all the memories together and they live together in one world, with no division or barriers. I don’t like barriers, either physical or mental.

“I believe that fashion can say something. It’s not about intellectualism, it’s about delivering something that you believe in, and not only clothes. Because people don’t need clothes actually. So unless something touches you in terms of emotions or feelings, you don’t need a new T-shirt. There’s something Diana Vreeland said that I really like: ‘Don’t give them what they want, let them want what you give them.’ You don’t have to give answers, and sometimes you can give questions. I like the idea of people watching the show and thinking, ‘I didn’t know it, but this is what I really want.’”

Despite your success, you’ve maintained a low-key lifestyle: you work in Rome, where you studied, and you live in Nettuno, a small seaside town 60 kilometres away, where you were born. Is it important for you to inject a little bit of soul into the globalized world of fashion?

Definitely. It’s good for me to be the creative director of a huge company but to retain a personal, sometimes even intimate, approach. I think that people make all the difference. The system is made by people, even in a huge company. If you don’t have that, things become too big and generic. The digital world and social networks are a huge opportunity to put forward your own authenticity. Whether you work in Rome or Paris should make a difference. I started to love Instagram when I saw the photoblog Humans of New York: it’s a place where you can tell personal stories, an opportunity to feel the intimacy and share the emotions behind something that is huge and global. Living in Nettuno gives me both strength and balance. I think it’s important not to forget your own identity. I don’t live in a castle, but I’m here because of who I am. And I want to stay the same. I don’t want to change, otherwise I feel I wouldn’t be authentic

Valentino Garavani, the founder of the brand, has lived a very jetset life. Was there ever a time when you felt you ought to conform to that model?

Mr. Valentino’s lifestyle is authentically him. When I was young, I asked myself if I had to be very jet-set and glam in order to be a creative director, because of course there are clichés about this. But I understood fairly early on that it was possible to keep my identity. It was impossible for me to become someone I’m not, so I understood that I had to put my own identity into the work. I’m a creative director who lives in Nettuno, away from the big city. I don’t usually go to parties, I’m not a socialite – although if I want to go I do. My freedom is very important to me. I also believe that fashion can say something. It’s not about intellectualism, it’s about delivering something that you believe in, and not only clothes. Because people don’t need clothes actually. So unless something touches you in terms of emotions or feelings, you don’t need a new T-shirt. There’s something Diana Vreeland said that I really like: “Don’t give them what they want, let them want what you give them.” You don’t have to give answers, and sometimes you can give questions. I like the idea of people watching the show and thinking, “I didn’t know it, but this is what I really want.” It’s about connecting with the Zeitgeist.

Do you think that, despite its histor ic traditions, c outure c a n express the Zeitgeist?

I think that what you don’t see is what makes couture very special. Rituals are part of the couture process. I like couture as a culture, not just as clothes. I like the people that are behind couture, the care they take in every creation, the love, even the poetry of spending months working on the same garment. You feel it when you see the inside of the clothes. I wanted to give value to this whole process while doing couture for modern times. Fifty years ago a woman who bought couture would buy only that. Now the client who buys couture also buys ready-towear. So I felt I needed to give them separates – it’s not about a suit anymore. Instead it’s about building the outfit layer by layer. Putting a trench coat on a dress that was made by a different department is totally outside of couture rules – it was hard to talk to the atelier about this idea of separates, it’s very different from what they usually do. But once I’d explained it, they were really happy to do it. Sometimes I asked them to use a sewing machine for a trench coat, because if you sew it by hand you lose the authenticity of what a trench coat is. There are young people working in the atelier, so I really want to push towards the future. What makes it couture is how the pieces are made, the tradition – you can have trousers or a T-shirt made the couture way. It’s an experience, and you know why you paid more, because it’s made to measure, even if other people don’t necessarily know that it’s couture.

What made you want to become a fashion designer?

I had the feeling that with fashion you can tell stories. Before fashion I was fascinated by cinema. I didn’t really make a decision, everything happened later, I felt passionate enough to work in fashion. I still feel very lucky to do a job that I’m passionate about. I don’t feel the pressure of the job, more the freedom to do something that comes directly from me.

No pressure? Yet you constantly have to come up not only with couture designs, but also with men’s and women’s ready-towear, accessories…

I like the idea of working with all these layers. Valentino is a beautiful house, which is quite capable of being contemporary and cool. I like doing couture as much as I like working on our advertising campaign for the Rockstud Spike bag, for which Terry Richardson and I stop people on the street and film them carrying the bag with their own clothes, just as they are. It started with the idea that bags often are status symbols, and they tend to overshadow the person who carries them. The campaign with Terry shows how a bag can be adapted to different looks. I really like the tension between high and low, street and couture – I think that that’s modern life.

People talk a lot about inclusivity these days, whereas traditionally couture was always about exclusivity. Would you say inclusivity is important to you?

Yes, I think inclusivity is very important. We can stress the same idea in dif ferent ways, between men, women, couture. For women I was thinking about what you might term narrative blocks: the romantic side, the ethnic, sports, hip-hop. Hip-hop is actually a good image of my process, since it started by playing samples from other music in order to create its own sound. I think it encapsulates this idea of inclusiveness: being together, including every culture, every people. It’s like an invitation to progress in your thinking – even if you know something, it can be good to change your mind and look at things differently.